Bunker Mentality: Fortified Domesticity and the “Crazy Prepper” in 10 Cloverfield Lane

Greg Clinton | Stony Brook University

10 Cloverfield Lane (Trachtenberg, 2016) appears amidst a growing concern in American culture with apocalyptic futures, threats (real or imagined) to national security, and social change that seems to menace the heteronormative, patriarchal family unit. The film features what I have come to know as the “crazy prepper” character, a trope that evolved from earlier indictments of survivalists as dangerous paranoiacs, and is underscored by reality-style TV shows like Doomsday Preppers (National Geographic) and Apocalypse Preppers (Discovery Channel). What makes “crazy” in 10 Cloverfield Lane? In asking this question, I wonder more broadly about the meaning of fortified domestic space in America.

10 Cloverfield Lane offers up the prepper as a psychopathic predator (and ultimately a zombie, as I will argue) — it uses the “crazy prepper” to interrogate the concepts of reality, tradition, and risk. The film ultimately relies on stereotypes of preppers and prepping behaviors — bunker-building, stockpiling food and weapons, etc. — as insane or deviant to achieve its dramatic ends.

The film is framed as a drama about the destabilized family unit. Before the opening credits, we are treated to a miniature tragedy, acted without dialogue. A woman is hurriedly packing a small suitcase. She rushes out the door; the camera settles on two forlorn objects left behind: her keys and a diamond engagement ring. She is leaving her fiancée.

In itself, a woman walking away from the traditional patriarchal stability of marriage is thoroughly “modern” and a reflection of feminist and liberal progress. This scene can also be read as a reflection of traditions unmoored, of the tenuousness of all social structures, no matter how firmly established. Ulrich Beck, in his analysis of the unpredictability of modernity in what he calls “risk society,” points to the “tradition” of the heteronormative family unit as a locus of destabilization since it is both the foundation of bourgeois industrial society and a “contradict[ion of] the principles of modernity” in that it promotes a basic patriarchal inequality. [1] Thus, by progressively equalizing gender roles, the structure of “family” is undermined. The modern woman is liberated from the “fate” of gendered and sexualized hierarchies. At the same time, radical change encourages new anxieties.

The prepper, on this view, is the man who has constructed a defense of traditional patriarchy. John Goodman plays Howard, a prepper who has “rescued” a young woman, Michelle, from what he claims was a nuclear attack. In her rush to escape her impending marriage, Michelle’s car is run off the road. (Howard caused the crash intentionally, we learn much later.) She wakes from her trauma shackled in a basement, part of Howard’s underground fallout shelter. They cannot leave, Howard insists, since the air outside is contaminated and deadly. A young man, Emmett, is also in the bunker, having begged his way in soon after the “attack.” So the fortified domestic space mirrors an image of mid-20th century American middle class, with the father (knows best) and two (rebellious) children. The mother is absent; the law of the father defends this space, a law which is called deeply into question.

Early in her confinement, Michelle wonders why they haven’t tried to contact the authorities. Howard points to a police scanner: “There’s no one left to call. See that? There’s nothing coming through.” Then, holding his temple as if warding off a headache or the voices only he hears, he blurts, “You think I sound crazy. It’s amazing… You people. You wear helmets when you ride your bikes, […] you have alarm systems to protect your homes. But what do you do when those alarms go off? Crazy is building your ark after the flood has already come!” Howard hones in on the slippage from rationality to irrationality, the contest between sanity and insanity. We are forced, as viewers, to question the notion of sanity as that which corresponds to reality; reality, as we discover by the end, corresponds to Howard’s psychopathology, to the violence of patriarchal domination.

Howard’s shelter, where the majority of the action is set, is modelled after Cold War-era basement bunkers, although it is extravagant by the standards of a one-room cinderblock hovel. Introducing Michelle to the space, while the camera pans 360-degrees, Howard announces:

As you can see I’ve planned for an extended stay. The hydroponics system keeps the air fresh. Feel free to help yourself to any reading. If you want to watch movies, I have an extensive collection on DVD and VHS cassette[…] The kitchen is fully functional: it has an electric stove, refrigerator, freezer, silverware, and that dining room table is a family heirloom, which means watch your glasses.

A cross-stitched sign, “Home Sweet Home,” hanging above a juke box in the living room (piping out the 1967 classic “I Think We’re Alone Now” by Tommy James and the Shondells) underscores the irony of the home-shelter-dungeon.

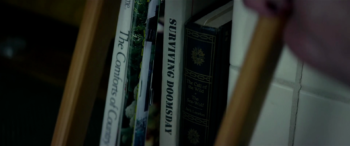

The centrality of the link between prepping and domestic space is subtly illustrated in a shot of Howard’s bedside reading: a double-edition of Jack London’s The Call of the Wild, a survivalist classic, and The Sea-Wolf, the plot of which parallels the film itself; a book entitled Surviving Doomsday, which might be an apocalypse survival manual by Richard Duarte (2012); and a copy of Country Home: The Comforts of Country, which is a 1995 interior decoration book with images of country-style homes for inspiration. Taken together, the three books form an odd but coherent framework for understanding Howard and the film by juxtaposing masculine independence, apocalypticism, and domesticity.

Howard means to exploit his position of patriarchal control. Beyond the “house rules” that Howard enforces, we learn over time that he plans to use Michelle as a forbidden sexual object, fetishizing her as a replacement for his absent daughter. He is a sinister photo-negative of Father Knows Best from 1940s and ‘50s TV. “Hands to yourself!” he declares, invoking a fatherly injunction against sibling rivalry, although the viewer understands this to mean Howard wants Emmett to keep his distance from the sexual target, Michelle. In a scene at the dinner table, Howard tries to maintain the pretense of familial decorum, but explodes when Michelle begins to subtly flirt with Emmett. Michelle’s subversion of the artificial sister-brother relationship reveals Howard’s desire for violent transgression. The ruse of familial care unravels.

This sense of perversion, of an uncanny domestic space in which sexual taboos may be violently violated, is heightened by Howard’s insistence that he is “not some kind of pervert” when he resolves to keep an eye on Michelle as she urinates; he watches her “for [his] own protection.” The strength of his disavowal of perversion is subtly ironic; the viewer and Michelle are immediately suspicious of everything Howard says. What is true, what is false, what is sane, what is perverted: all these are entangled in the bunker.

In her attempt to escape, Michelle out-maneuvers Howard by dumping a barrel of toxic chemicals, burning Howard’s body and face, transforming him momentarily into a zombie, fully revealing the “truth” of the father as monster. Michelle escapes to the outside world… where she actually encounters an apocalyptic alien invasion.

The inside, it turns out, is as awful as the outside; but outside, Michelle has the chance to become an action hero, a woman of action. She is super-able, over and against the zombie-patriarch. After skillfully dispatching some aliens, Michelle drives off in search of the resistance movement. The bunker defends patriarchal domesticity, an interior dystopia whose laws are violent and in which the “crazy prepper” is installed as the ultimate American pragmatist whose goal is to entomb and enshrine “the family” while denying the potential for action in an exterior reality that undermines those power structures.

Image Credits:

1. Author’s screen grab.

2. Author’s screen grab.

3. Author’s screen grab.

4. Author’s screen grab.

5. Author’s screen grab.

Please feel free to comment.

- Ulrich Beck, Risk Society: Towards a New Modernity (London; Newbury Park, Calif.: SAGE Publications Ltd., 1992), 104. [↩]

So do you think the film’s characterization of preppers is inaccurate?

Or are real-life preppers in fact striving to preserve the heteronormative, patriarchal family unit?

Both. I think the film unfairly and unrealistically casts prepping as inherently psychopathological – this is why the audience can readily accept that the prepper is insane or psychologically troubled – but at the same time preppers are typically interested in protecting “the family”, which they see as the “ultimate responsibility” for a man.