“Always Off” Connection

Germaine Halegoua / University of Kansas

The proliferation of “smart cities” has called attention to the ways that cities have always been “smart.” Journalists and urban theorists referred to “smart cities” of the 1940s as “nerve centers” or technologized coordinating hubs for the flow of goods, services, communications, and people. [1] At the beginning of the 1900s, “smart cities” such as Chicago, New York, Paris, London, and Singapore implemented technologies that networked people and places to provide efficient and convenient exchanges across urban space through rail and highway routes, waste management and utility systems, electric grids, and telegraph lines.

Considering the city as perpetually “smart” encourages scholars to engage with infrastructure and relationships to infrastructure as palimpsests. [2] The deepness of the city as platform is accumulated and reconfigured over time. Infrastructures reveal contingent, cumulative narratives of media and place that inform material and cultural histories and understandings of political, economic, and social practices. [3] Historians have highlighted how media networks often echo logics and routes of their predecessors, having been “built on an installed base.” [4] Transportation, electricity, and telecommunication networks are physically laid atop each other and are influenced by preceding infrastructural affordances and constraints. Nicole Starosielski encourages scholars to imagine infrastructure networks as “entangled” and embedded within natural and social environments. For example, she explains that although network providers often attempt to disentangle rural fiber optic cables from topographic and forestry patterns, wind speeds and snow storms, infrastructures remain enmeshed within “pipeline ecologies” of natural, socio-technical, and agricultural landscapes. [5]

Several methods can be employed to study infrastructural entanglements. Shannon Mattern suggests that “urban media archaeology” of the media city – a multi-sensory method for exploring materialist histories of urban history and culture – can expose infrastructural interactions that produce the city as networked place. [6] This method is related to Lisa Parks’ call for mapping and fieldwork as practices toward “infrastructure re-socialization.” Through mapping, members of the public are able to cultivate literacies that enable them to interrogate and analyze material properties, ownership models, and politics of infrastructure networks. [7] In addition, Star and Larkin have both suggested the value of conducting ethnographies of infrastructure, which account for different socio-cultural conditions that shape meaning, affect, and experience of infrastructure. For the remainder of this essay I want to think about how these methods might be united to study under-investigated networks within infrastructure studies: networks of “always off” connection.

By “always off” connection I am referring to networks that are purposefully constructed as dark or inactive. Passive networks that are built, buried and lay dormant until activated months or years after installation, or may remain “off” indefinitely. Imaginations and investigations of cities and towns as configured networked spaces highlight active or once-active networks: pneumatic tubes, postal services, broadcast towers, missile silos, wireless frequencies and data centers, satellite systems and undersea cables.

Scholars focus on historiographies and analyses of the labor involved in maintaining and running active or once-active networks and past or present experiences of use. But what is the cultural and technological work of an inactive network? Can we use “urban media archaeology” to uncover and study telecommunication, transportation, and cultural networks that were built but never activated? What stories can be told about a city, suburb, or rural environment by looking at dormant networks? What can “always off” connections tell us about relationships and power structures around place and digital media?

While an existing yet dormant network might describe evacuation routes, emergency, supplemental or backup infrastructures, I’m interested in networks of dark fiber – fiber optic cables that are buried under streets and sidewalks but remain unlit. Since there is no light pulsing through the cable, no data can be transmitted, therefore the cables are “off” or inactive. These are not networks that were once active and then extinguished; they are publicly or privately-owned fiber optic networks that are conceived as “dark.”

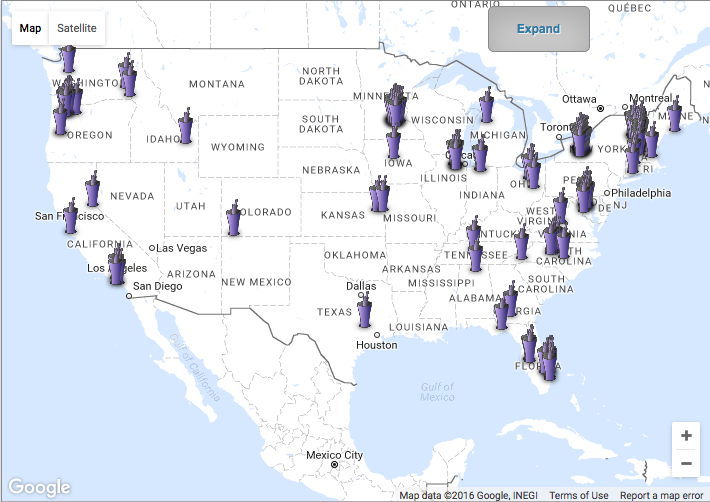

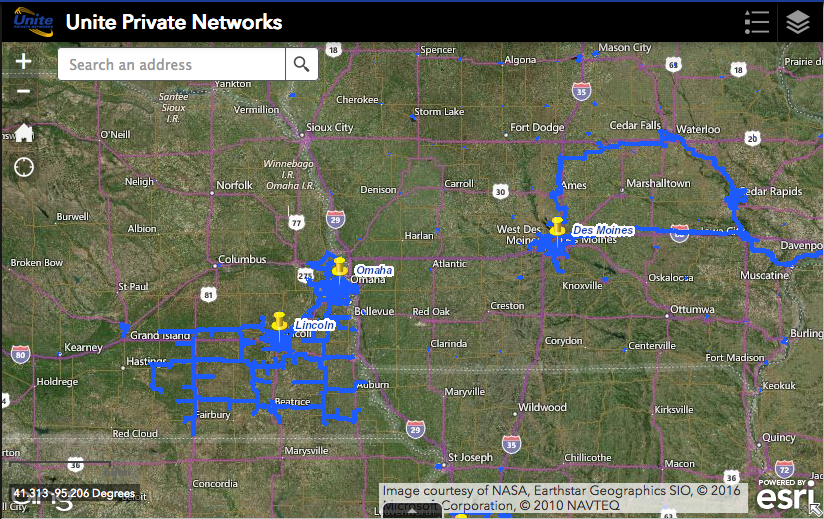

As an alternative to claims that infrastructure is made visible through breakdown or blackout, dark fiber becomes intelligible when it is turned on. Although members of the public are often ignorant of dark fiber until it is lit, these networks are not intentionally hidden or concealed. On the contrary, these fiber networks are for sale or lease to Internet Service Providers (ISPs) who can light and extend them for residential, commercial, or government use. The companies that own and install these networks such as Zayo, Level 3, Unite Private Networks, and American Fiber Systems may lease fiber to Comcast, Verizon, or Alphabet’s Google Fiber. Cities such as Roanoke, VA, Huntsville, AL, and Centennial, CO have built their own “open access” dark fiber networks to encourage local investment and competition among ISPs. Broadband activists and researchers are enthusiastic about the potential of dark fiber for more equitable and geographically dispersed Internet provision. [8]

Mapping, ethnographies, and media archaeologies of dark fiber challenge established cultural geographies of infrastructure and networked spaces. Dark fiber maps reveal that mid-sized or small cities like Lincoln, Nebraska or Huntsville, Alabama are quite infrastructurally sound in terms of substrates for digital connection. Or that rural towns and in-between spaces that lack broadband connection actually reside on dark fiber routes that have bypassed their neighborhoods for years. Studying “open access” dark fiber networks offer several unique moments where the geopolitics of infrastructure become visible and the creation of meaning, desire, and potential for networks are expressed. Aside from infrastructure construction and implementation processes, decisions around dark fiber leasing and activation highlight how certain places, populations, and uses may be valued over others. Some distinct questions that emerge include: where do cities, corporations, or broadband authorities lay fiber and what are the cultural and network geographies of where the network is turned on, and for what purpose? Mapping and archaeologies of dark fiber emphasize latent politics and regulations around access to fiber networks – who gains access and on what terms? “Always off” connections offer new opportunities to explore how ISPs engage with and imagine Internet backbones and their role as service providers. In addition, evaluations of time and historicity shift to include not only questions of when and why dark fiber networks are installed, but also how long, where, and why these networks have remained inactive? How long have these networks, cities, and towns been characterized by their potential for connection?

If we are to examine infrastructural entanglements and ecologies as formative entities in the conceived, perceived, and lived experiences of place, then we need to consider always “off” connections more explicitly. Deep maps of infrastructure should include physical and social traces of dark fiber alongside other transportation, communication, and telecommunication networks to reveal interactions and incongruences between past, present, and future networks. Studying these networks expand and complicate our understanding of the materiality and cultural geography of connection and disconnection, infrastructure materiality and literacy, and the actors and forces that entangle and disentangle networks in our daily lives.

Image Credits:

1. Image courtesy of author’s personal collection

2. Image courtesy of author’s personal collection

3. Institute for Local Self-Reliance

4. Unite Private Networks

Please feel free to comment.

- Albert Lepawsky, “City Plan: Metro Style,” Journal of Land & Public Utility Economics 16, no. 2 (May 1940): 137–50. [↩]

- Shannon Mattern, Deep Mapping the Media City (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2015. [↩]

- Brian Larkin, “The Politics and Poetics of Infrastructure,” Annual Review of Anthropology 42, no. 1 (2013): 327–43. [↩]

- Susan Leigh Star, “The Ethnography of Infrastructure,” American Behavioral Scientist 43, no. 3 (November 1, 1999): 382. [↩]

- Nicole Starosielski, “Pipeline Ecologies: Rural Entanglements of Fiber-Optic Cables,” in Sustainable Media (New York: Routledge, 2016. [↩]

- Mattern, Deep Mapping the Media City. [↩]

- Lisa Parks, “Earth Observation and Signal Territories: Studying U.S. Broadcast Infrastructure through Historical Network Maps, Google Earth, and Fieldwork,” Canadian Journal of Communication 38 (2013): 285–307. [↩]

- Susan Crawford, “You Didn’t Notice It, But Google Fiber Just Began the Golden Age of High Speed Internet Access,” Backchannel, March 3, 2016. [↩]

There are many essential things in our computer, if we lose it, then we have trouble, that’s i have searched a very useful site where we can keep our backup files safe and learn more related things.