Flow’s Community: Reflections in 2016 on Flow 2006

Allison Perlman / University of California – Irvine

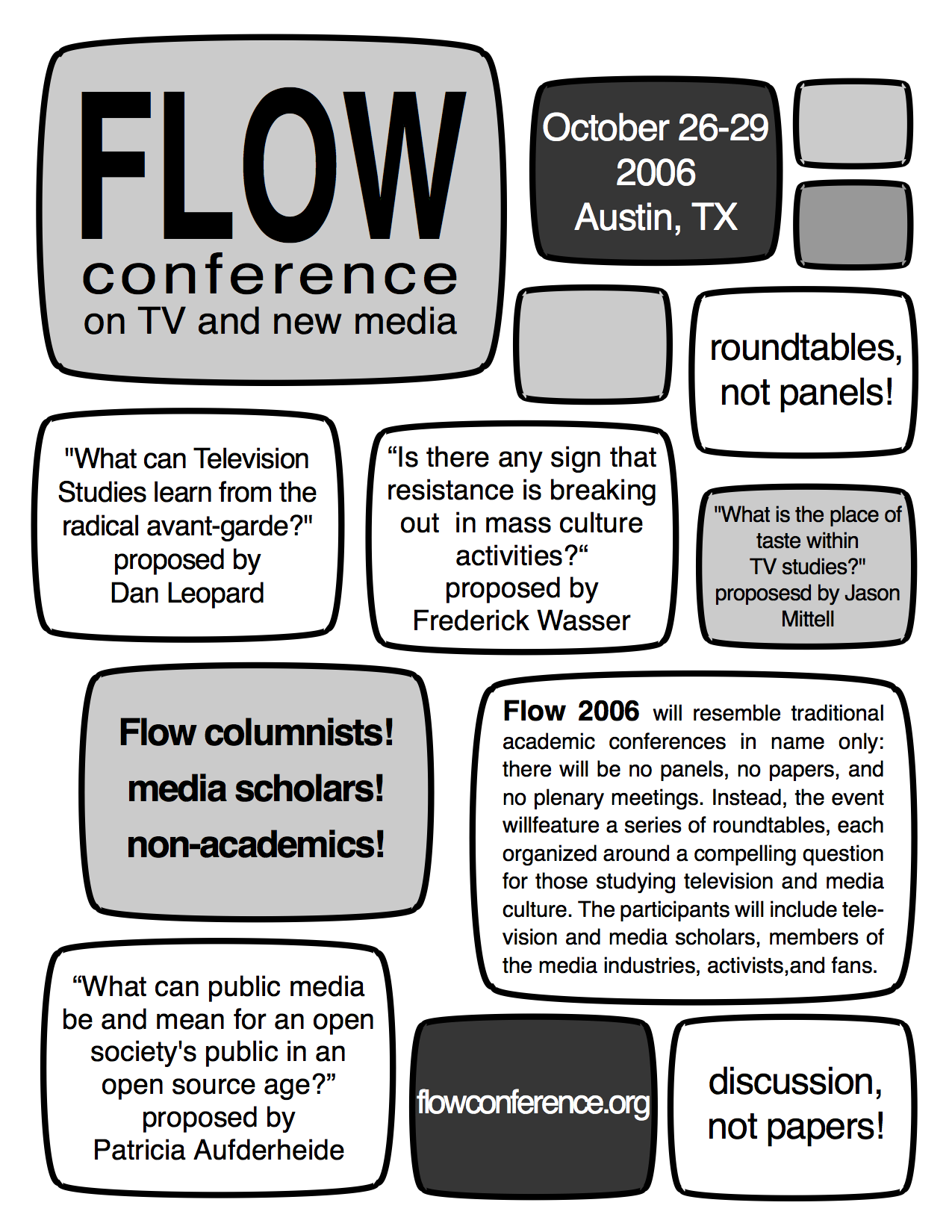

For the inaugural Flow conference, we devised a pretty complicated system to constitute panels. It was confusing to our participants, and even those of us on the organizing committee frequently had to remind ourselves of the rules we had mapped for this process. Conveners could invite two people to participate, the Flow organizing committee could invite two people to participate, and the remaining panelists would be drawn from the pool of applicants who responded to the CFPs announcing each roundtable’s central question. Our primary goal in doing it this way was to leave spots on each roundtable for non-academic participants whom either we or the convener would invite to the conference. If the goal of Flow was–and is–to promote conversation, our sense was that these discussions would be richer if, as we talked about industry trends, fandom, and the politics of television, at the table were industry professionals, fans, and media activists. This vision of the conference aligned with our goals for the Flow journal – to create a space for multiple communities interested in television to think together about the medium’s meanings and its changes.

It is hard to overstate how the emphasis on conversation, rather than on the presentation of and response to pre-written papers, was critical to the success of the first Flow. Across the roundtables, there was so much joy and energy and relief to have the space to talk about, for instance, approaches to teaching about television, the uninterrogated assumptions that guide how we determine which television texts are deserving of inquiry, and the relationship between media studies and other fields of academic research. Flow provided a profoundly valuable space for us to speak to one another, to bat around ideas and pose questions that affect our practice but rarely get discussed in a public setting.

But while these conversations were productive and wonderful for the academics in the room, they did not leave a whole lot of space for the non-academics to participate. While many of the non-academics at that first Flow made highly valuable contributions to their roundtables, I sensed that overall they felt that they were only tangentially involved in the conference, their ability to jump in to the discussion sometimes limited by the direction in which it went. Much of this, as organizers, was our fault. As we trained our graduate student roundtable moderators, our emphasis was on how to keep the conversation going, on how to assure that certain individuals did not dominate; we did not think through with them how to cast the discussion so that it did not seem insular to the faculty and the graduate students in the room.

Our relationship with people outside the academy about our work has been a longstanding concern for television scholars. On one hand, as Amanda Ann Klein and Kristen Warner recently have discussed, scholarship on popular culture rarely informs the popular press that it receives, a trend that speaks to the continued devaluation of the work we do and the expertise that informs it. Given the elevation in television’s cultural status in our contemporary moment–and the gushing assessments of its cultural worth in myriad publications–the work of television scholars seems especially critical to the broader conversation over what television does, how it means, where it circulates, who it is for, the labor conditions in which it gets made, the questions that it raises. In other words, it is to everyone’s disadvantage for television scholarship to remain cordoned off, read only within the confines of university classrooms and exam lists, with little impact on the wider dialogue about television practices in the twenty-first century.

In addition, on the other hand, our own work often relies on access to people who work within the industry, fans of particular series, activists engaged in struggles over the politics of representation and of distribution. So much critical television scholarship could not be done were it not for the generosity of those who share their stories, their perspectives, their documents with us. These relationships are both informative and generative and, speaking personally, have altered how I have thought about the questions that guide my research and the assumptions that led me to them.

And so fostering dialogue across communities interested in television is unquestionably important–indeed, is vital–but I think what we learned at the first conference was that Flow perhaps was not the place best suited to do this, that there was a need within our own community to have a space to talk to one another. While subsequent Flow conferences have included special panels for, for example, people who work in the industry, my sense is that the roundtables nearly exclusively have been filled by academics, the somewhat byzantine process we used to people them abandoned for a more streamlined and familiar conference method. The Flow journal, for which we had similar aspirations, also seems to be contributed to and read predominantly by students and faculty within media studies.

Going forward, I wonder the degree to which such a realization could inform the subjects of panels. If Flow is the site where we can ask each other tough questions about what we do–in our scholarship, in our classrooms, in our relationships with colleagues in other disciplines, and in our connections to communities outside academe–how might that reconfigure what seems like an important question to ask for a roundtable discussion?

Image Credits:

1. Flow 2016 logo

2. Flyers in 2006… (journal document).

3. Even with the best of intentions… (author’s screenshot).

Please feel free to comment.

Dear Allison, I am very impressed by the candor with which you address the difficulty of spawning thoughtful conversation in this type of forum between academics and non-academics. Indeed, we do benefit greatly from our more structured conversations with people actively working in the media, and we would hope that what we have to say might be of interest to them – not just in print, but in the manner of brainstorming around tough questions confronting a variety of media forms and discourses at the crossroads today. Yet this is a question of relevance not just to a conference purposely organized around a día logical principal (Bakhtinian reference intended), but to many of the conversations that we hold on college campuses. Is it the venue that stifles that flow? Or is it our reluctance to let go of our own modes of argumentation and presentation? Perhaps we might think less of a “results” driven approach – that what we say might end up in print – and simply a sharing of ideas without an immediate concern for authorship? Perhaps it would help balance things out if we also went to the venues and forums organized by practitioners and producers where we academics are in the minority, and try sharing our ideas there? I’ve enjoyed that challenge,and have learned a lot from those encounters. In any case, until I read your post, I wasn’t aware of the extent to which non-academic professionals participate in FLOW, and am looking forward to that ambience.