There’s a Place for Us: Finding a Home for Theater in Media Studies

Peter C. Kunze / University of Texas at Austin

Last month, two noteworthy moments in media history took place–though we might not understand them as such. On June 12, Scott Rudin won Tony Awards as the producer of the Best Play (The Humans) and the Best Revival of a Play (A View from the Bridge) on top of his four other production nominations. Two weeks later, BroadwayHD, a NetFlix-like service offering recordings of Broadway shows, streamed She Loves Me live from Broadway for paying customers online. Rudin’s win highlights a career split between Broadway and Hollywood, where he has numerous productions to his credit (including the Oscar-winning Best Picture, No Country for Old Men) and a good deal more to come. (Next year alone, he has already announced three star-studded revivals: Nathan Lane and John Slattery in The Front Page, Sally Field in The Glass Menagerie, and Bette Midler in Hello, Dolly!) BroadwayHD reveals a fascinating intersection between the theater and new media technologies, offering individuals who might never make it to New York City or even the nearest theater the opportunity to see a stage musical in real time with its Broadway cast. Taken together, these events reveal not only the crossroads of theater and media, but theater as media.

My goal here is to argue for the greater inclusion of theater in the studying and teaching of media. Obviously, the theater is of great importance for scholars of early cinema, since much of the talent on stage and behind the scenes transitioned from the vaudeville or Broadway stages to the studios around New York City and later Los Angeles. Film theorists, from André Bazin and Sergei Eisenstein to Susan Sontag and Tom Gunning, have understood the phenomenon of film through and against theater. Since those early days of studio filmmaking, Hollywood pursued an active, albeit often tense, relationship with Broadway. Stars tried, with varying degree of success, to move between the stage and screen. The New York stage not only provided a testing ground for new talent, but a venue to work out new material. Not everyone welcomed this partnership, of course. Influential drama critic Brooks Atkinson lamented the Hollywood-bankrolled Broadway shows seemed better suited for the screen than the stage, since they were often less artistically daring and required numerous scene changes. [1 ] Indeed, Broadway’s flop often became Hollywood’s next spectacle.

In the 1960s and 1970s, several musicals reversed the Broadway-to-Hollywood pathway, as Hollywood movies provided the source material for Broadway hits, including Carnival!; She Loves Me; Promises, Promises; and Sugar. The rock musicals of the late 1960s and early 1970s (Hair, Godspell, Jesus Christ Superstar) followed by the blockbuster spectacles of the 1980s (Cats, Phantom of the Opera, Les Misérables) proved that Broadway was not immune to the blockbuster mentality that took over Hollywood in the late 1970s. The turn of the 21st century saw more film-to-stage musicals, and then a full circle: the movie musical based on a stage musical based on a movie, including The Producers, Hairspray, and Nine (based on Fellini’s 8½). Furthermore, transmedia storytelling might be extended to the stage, especially as Disney expanded Beauty and the Beast for its Broadway adaptation in 1994 and fans of Harry Potter are currently flocking to see the play Harry Potter and the Cursed Child in the West End of London. Today, companies such as Disney not only license their creative properties for merchandise, but also for amateur stage productions starring children. In an age of convergence and conglomeration, theater has a rightful place alongside film, television, and new media.

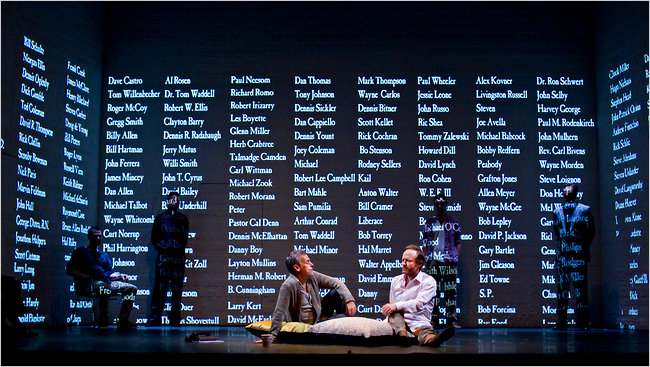

A common assumption is that the essence of theater is its intimacy and immediacy–the sense that it is not mediated. Of course, in reality, the theater has long depended upon mediation. One could easily argue the body and the voice become media in live performance. Media technologies have also made their way into numerous productions, especially major Broadway shows. The 2005 production of Andrew Lloyd Webber’s The Woman in White used animations projected on a curved screen in lieu of more traditional set designs, while a 2011 production of Larry Kramer’s The Normal Heart projected a growing list of names of AIDS victims onto the stage to underscore the disease’s devastating impact. A cinematic-style rear projection in the recent West End production of Gypsy cues the audience that Mama Rose has hit the road, while The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Nighttime employs a complex lighting design and projections to represent the protagonist’s mind. We could even go back further to consider the controversial use of microphones, speakers, and pre-recorded sound in the theater in recent decades. In Broadway: The Golden Age, Jerry Orbach lamented, “Now miking in the theater not only changes the theater, but kind of destroys it. It’s not the same experience. It’s not live. Live is unmiked.” Media and media technologies have fundamentally changed what theater is and how one can and should experience it.

For example, the theater has long depended upon paratexts and ancillary products, like programs, playbills, and, more recently, merchandise. In 1957 and 1958, the Original Broadway Cast recording of My Fair Lady was the best-selling album in any genre in the United States, while The Sound of Music, Camelot, and Hello, Dolly! were the most popular in 1960, 1961, and 1964, respectively. (The soundtrack to West Side Story topped 1962 and 1963.) Last year, Hamilton had the most successful cast album debut in nearly 50 years, even making an appearance on Billboard’s Rap Album chart. [2 ] Indeed the massive popularity of Hamilton far eclipses those who have been able to see it on stage, suggesting that the theater experience exists for many by way of these related media products, be it the album or the recently released companion book. Broadway fans not only sing their favorite showtunes and collect signed playbills at stage doors; they can buy the T-shirt, the DVD recording, the keychain, and the coffee mug. Furthermore, series such Fox’s Glee and the CW’s Crazy Ex-Girlfriend make direct appeals to Broadway fans. Rachel Bloom, co-creator and star of Crazy Ex-Girlfriend, considers herself an avowed Broadway fan, and many of the principals have backgrounds in musical theater. Attentive viewers also will notice several of the series’ original songs are passionate homages to canonical musicals like The Music Man, Company, Dreamgirls, and Les Misérables.

Just as Hollywood’s profits are soaring, so, too, are Broadway’s. In both 2014 and 2015, Broadway grossed over $1.3 billion, [3 ] and with shows on the boards that are produced by either Hollywood producers or conglomerates like Disney or Warner Brothers, those of us interested in media industry studies will be well-served paying more attention to this effort at diversification. Granted, Broadway shows may not regularly yield the same profits as Hollywood films, but they can extend a franchise or brand and maintain the commercial viability of said entities. In some rare instances, however, Broadway shows and their national and international tours have grossed amounts that rival or even eclipse the biggest Hollywood blockbusters; in 2014, Deadline Hollywood reported Disney’s stage version of The Lion King had grossed $6.2 billion. [4 ] This potential for high profits, however, has meant more members in a production team, bigger budgets, more revivals of proven properties, and higher ticket prices–news that Broadway denizens have regularly lambasted. This industrial transition will sound familiar for scholars of film and television.

Admittedly, one reason that theater has received limited attention so far is that it is its own field: theater and performance studies. Rather than see this fact as a deterrent, we might embrace it as an opportunity to pursue interdisciplinary scholarship and collaboration. Greater consideration of performance might also push us to explore other aspects of conglomerates’ site-specific media endeavors, such as theme parks, film and music festivals, and awards shows. While I have privileged Broadway in this discussion, we could — and should — follow the lead of our colleagues in theater history and criticism by equally turning our attention to off-Broadway, touring, regional, and local productions. If the play’s the thing in which Hamlet catches the conscience of the king, theater might just prove to be another generative inroad to better understand the logics, practices, and products of the historical and contemporary cultural industries.

Photo Credits

1. Rudin wins for The Humans – New York Times

2. Brooks Atkinson – Theatrical Intelligence

3. Harry Potter and the Cursed Child – BBC

4. The Normal Heart – New York Times

5. The Lion King – NewYork.com

- Brooks Atkinson, “Hollywood Dough,” New York Times, November 10, 1935 [↩]

- Keith Caulfield, “Hamilton‘s Historic Chart Debut: By the Numbers,” Billboard, October 7, 2015, available at www.billboard.com/articles/columns/chart-beat/6722015/hamilton-cast-album-billboard-200. [↩]

- Gordon Cox, “Broadway Box Office Rings in $1.35 Billion in 2015, Gets Record-Breaking Start to 2016,” Variety, January 4, 2016, available at variety.com/2016/legit/news/broadway-box-office-2015-records-1201671519/ [↩]

- Jeremy Gerard, “Hakuna Matata, Baby: Disney Claims Record $6.2 Billion Gross for Lion King,” Deadline Hollywood, September 22, 2014, available at deadline.com/2014/09/disney-lion-king-highest-grossing-show-at-6-2-billion-838482/ [↩]

Pingback: Volume Blog