“Its Not Just a Doll; It’s a Social Movement”: Investing in Black Toys Then and Now

Avi Santo / Old Dominion University

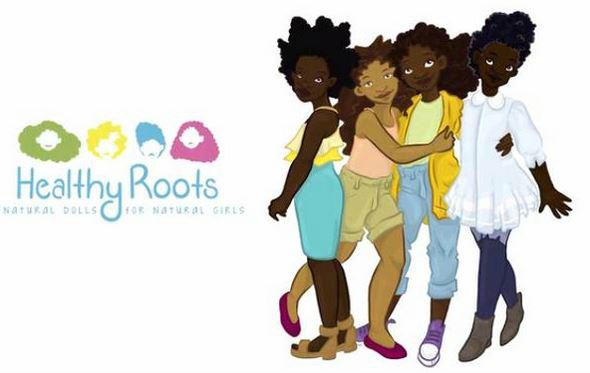

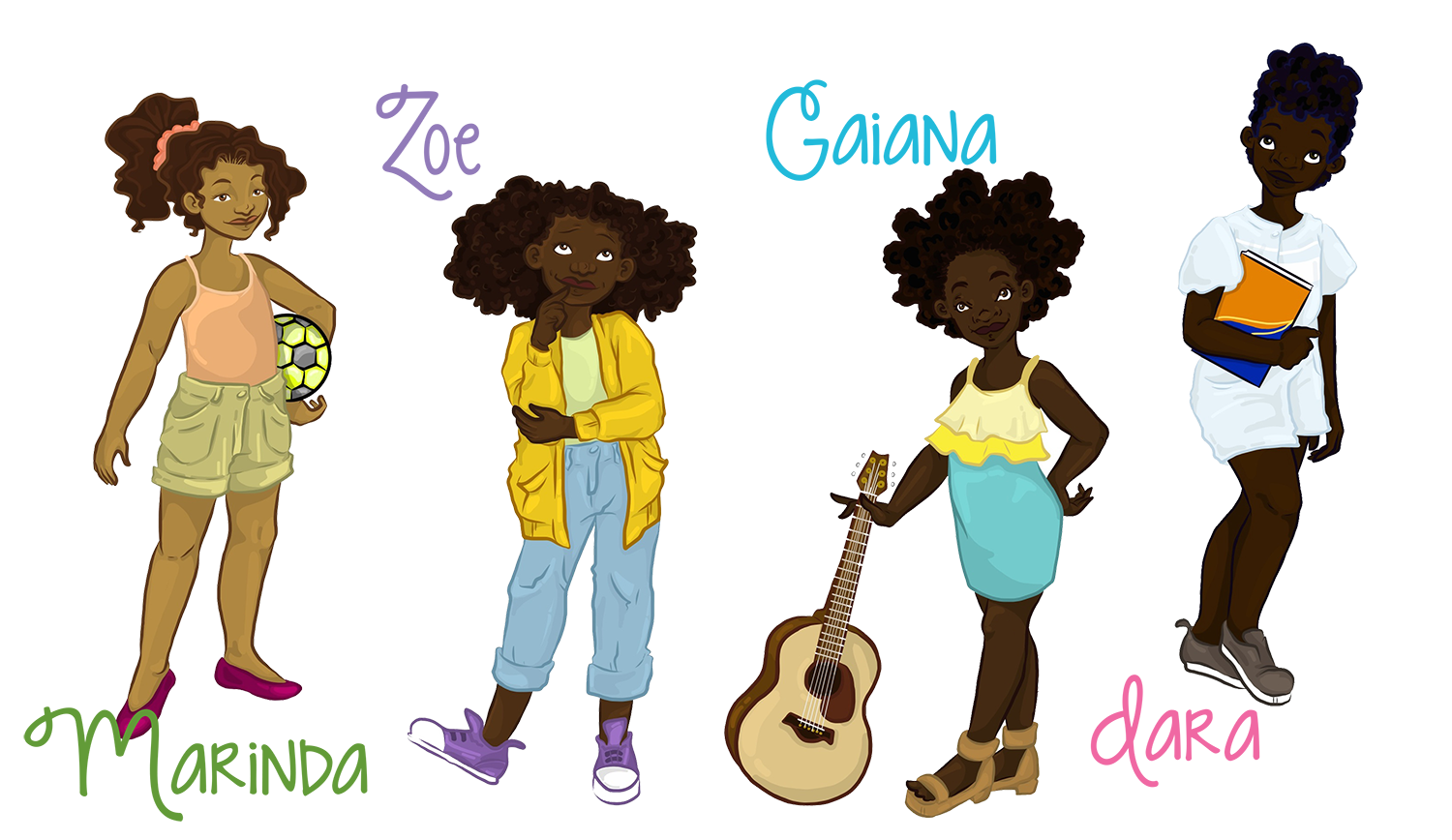

In my previous post I explored some of the rhetorical and representational strategies used by toy start-ups pitching STEM products for girls through crowd-funding sites like Kickstarter and Indiegogo. In this post I want to compare those campaigns with ones for toys aimed at African American girls and focused on helping them to overcome internalized racism and colorism with regards to their appearance. Healthy Roots and Naturally Perfect successfully raised funds to manufacture lines of dolls that came in different skin tones (yet all identified as “Black”) featuring hair similar in texture to African American women that could be styled in ways evocative of the African diaspora. I also compare these crowd-funded initiatives with an earlier attempt by Shindana in the mid-to-late-1970s to produce toys for African American children. In triangulating Healthy Roots and Naturally Perfect’s campaigns in relation to GoldieBlox and Shindana I hope to capture how notions of play and of power operate differently today for African American-led ventures into children’s culture.

Much like with their STEM-toys-for-girls-focused peers, Healthy Roots and Naturally Perfect foreground the organic relationship between their company’s founders and the products they were pitching. Both Yelitsa Jean-Charles and Angelica Sweeting positioned themselves as African American female entrepreneurs whose desire to empower young Black girls went hand-in-hand with their identification of a notable gap in the market that their products could fill, thus walking that fine line required of social entrepreneurship in linking ‘doing good’ with ‘making money.’

Unlike Debbie Sterling (GoldieBlox), Jean-Charles and Sweeting downplayed their pioneer status in favor of foregrounding their own victimization by societal beauty standards as inspiring their endeavors. If the former talked about wanting more girls to follow her into careers in science and engineering, the latter reminisced about feeling ostracized as children and frustrated with their own appearance. Jean-Charles begins her pitch by noting, “Growing up, I suffered from many insecurities about my skin color and hair texture. I was often told that in order to be beautiful you had to have long, flowing hair or fair skin.” Meanwhile, Sweeting explains how developing the Angelica Doll proved therapeutic: “As I began to develop The Angelica Doll and give serious thought to the things I wanted to do for young girls, I realized that I had been influenced by society’s standard of beauty for as long as I could remember. Here I am – 27 years old, and I am honestly just beginning to walk into who I am, my natural beauty.”

While I have no reason to doubt either of these women’s claims, their rhetorical focus on personal journeys toward self-love over career and education-driven aspirations (Jean-Charles identifies as a children’s illustrator while Sweeting offers no information about her career path other than being a wife and mother) is somewhat revealing of how white privilege works. Where Sterling et al. advocate for toys that get girls excited about science, engineering and technology, Jean-Charles and Sweeting suggest that Black girls first need to rebuild their self-esteem before they can aspire to barrier-breaking career choices. Tellingly, Sweeting offers “The Angelica Doll is a courageous, bold entrepreneur full of self belief, natural beauty, and perseverance.”

Though they positioned themselves as outsiders, both Healthy Roots and Naturally Perfect towed the industry line in positing toys as the solution to social problems while ignoring both the family and socio-economic environments in which play takes place. As Elizabeth Chin argues, it serves the economic and cultural interests of the toy industry to claim “it is children’s relationships with things rather than people that is most critically important for their sense of self”[1]. Healthy Roots asserts that “to solve [the] problem” of people of color being “told to change the natural texture of their hair in order to go to school or get a job” their doll line will “educate children and mothers about the joy and beauty of natural hair.” While there is little doubt that the Healthy Roots dolls might be tools that parents can use to encourage their children to appreciate their hair in the face of ongoing cultural stigmas and institutional racism, the dolls alone are not going to undo these problems. Yet, the assertion that instilling pride in how Black girls look at themselves will serve as a catalyst for action is built directly into the company’s mantra: “Healthy Roots is not just a doll. It is a social movement.”

Despite the rhetoric of transformation it is also important to note that A) both companies accept without question the notions that girls of any color want to play with dolls and that self-love is rooted in “broadening” beauty categories rather than overturning them. In this regard, these initiatives like the STEM-for-girls ones, re-inscribe and reinforce gender norms when it comes to play reassuring consumers that ‘change’ is truly skin deep while biology remains intact. B) Both sets of dolls are priced between $65-88 with an additional $30 required to acquire the Big Book of Hair that teaches kids how to style natural Black hair (whereas an 18-inch Frozen Elsa doll will cost $25-30 and your average children’s book is under $10). While this clearly makes the dolls unaffordable for most people (even as it acknowledges the existence of a middle-class Black constituency who might buy into the concept if not the actual product), it also speaks to limitations encountered by current-day toy entrepreneurs in terms of controlling manufacturing costs. Indeed, both Kickstarter campaigns identified their number one need as raising capital to meet manufacturer minimum order requirements, suggesting where the real product cost comes in (Naturally Perfect stated that it needed to raise $25K to meet the 1000 unit minimum demanded by its manufacturer, which works out to $25/doll excluding prototyping, packaging, shipping, and other expenses). And finally, C) Health Roots makes a point of connecting the ‘social movement’ inspired by its products to the need to “bring diversity to the toy aisle,” a correlation that again situates ‘change’ comfortably within consumerist ideals, but also seems oblivious to prior efforts to sell non-white toys at retail.

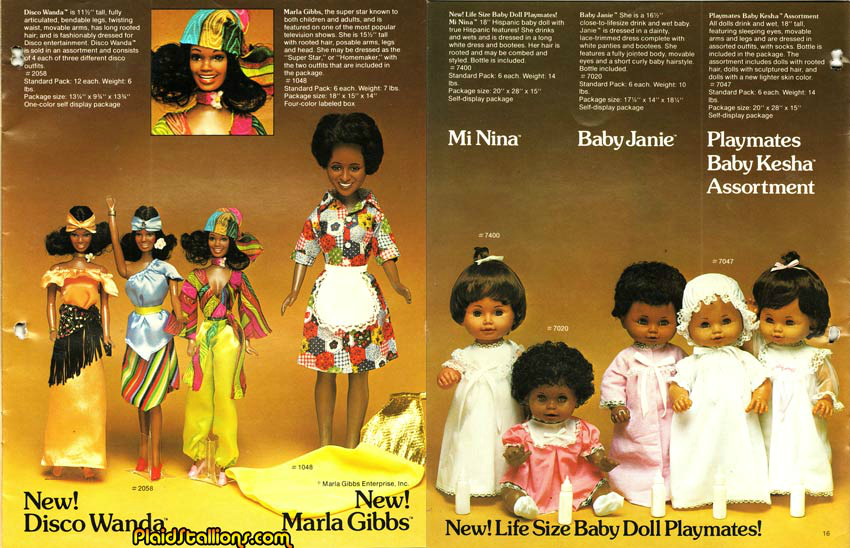

That neither campaign showed any awareness of the historical company they keep is not surprising; crowd-funding strategies demand a focus on the new rather than on continuity. Nevertheless, a quick look back reveals that there have been efforts beginning in the early 1970s to diversify toy lines. While early mainstream efforts like Mattel’s Colored Francie doll were met with criticism that they merely painted the dolls brown and used pre-Civil Rights era language like ‘colored’ to describe the toy [2], the rise of the Black-owned Shindana toy company in 1968 offers both a important contrast with and cautionary tale for today’s efforts.

Shindana, which means ‘competitor’ in Swahili, was an initiative launched by Operation Bootstrap following the 1965 Watts riots. Operation Bootstrap was a “self-help job training program” that emerged following the Congress of Racial Equality’s strategic shift from “nonviolent direct action to community organizing” [3]. The organization sponsored black-owned businesses in poor neighborhoods that fed part of their earnings back into their local communities in the form of jobs and infrastructure. The ideal of “profit-turned-to-education” was imagined as not simply improving lives in impoverished Black neighborhoods, but also leading to a politicized Black citizenship that had the clout and resources to push back against those in power [4]. As Lou Smith, Operation Bootstrap founder and Shindana’s CEO explained, “The answer I have come up with is that we must use the system’s weapon against it. It is a must that we establish our own economic base from which to finance our struggle… All the profits from these ventures should be used to finance the work of the organization as well as creating jobs for our ghetto-trapped brother… In short, we must inject the “soul”of the black community into the economic area” [5].

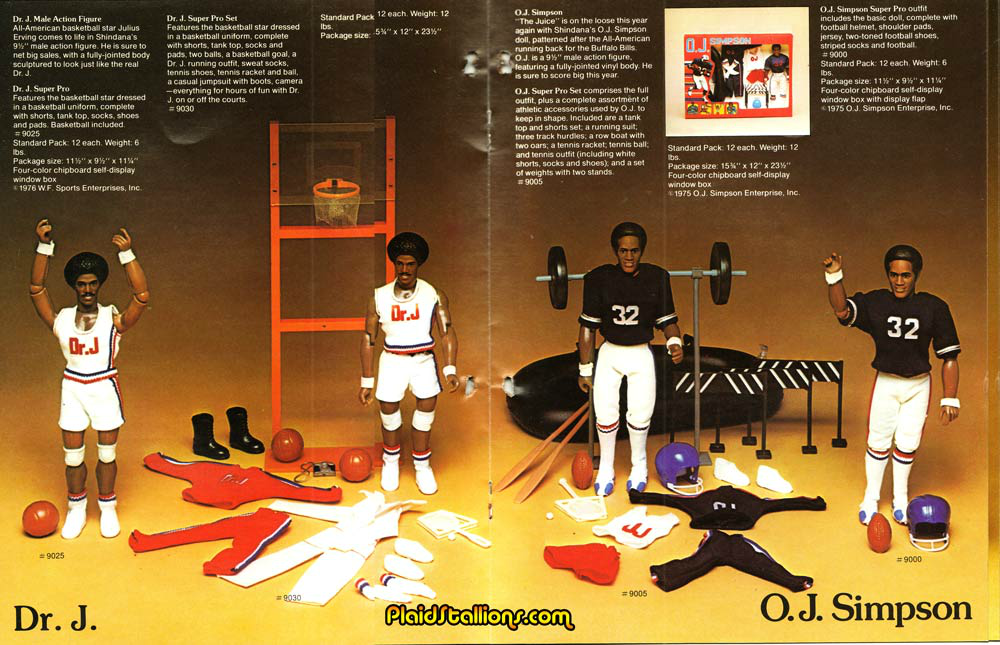

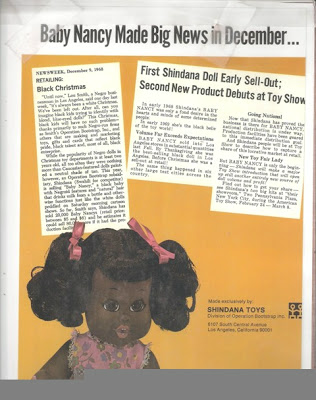

A significant aspect of Operation Bootstrap’s approach was a refusal to rely on federal assistance, instead looking to find investors among liberal-leaning members of the business community. Mattel gave Shindana an estimated $500,000 in loans and technical assistance to launch its operation. At its height, Shindana operated a factory in South Central Los Angeles that employed 70 people manufacturing dolls that were based on ‘ethnically correct’ Black features (Baby Nancy, Talking Tamu), Black celebrities (talking Flip Wilson, Red Foxx, and Jimmie Reeves plush dolls as well as plastic dolls based on the likenesses of Marla Gibbs and O.J. Simpson), and board games rooted in African American culture like The Jackson 5 Action Game and The Afro-American History Mystery Game. Sales reached $2 Million in 1975.

Ann DuCille suggests that Mattel’s investment in Shindana was not as altruistic as it may have seemed as the company not only used Shindana as an idea incubator for how to reach Black consumers but also piggybacked on the company’s early market success to release a new set of Christie dolls, billed as Barbie’s Black friend. The size of Mattel’s operation meant that it could manufacture toys in higher volume at lower costs, which in turn forced Shindana to begin importing parts from China to keep its pricing competitive leading to layoffs at the Shindana factory. To complicate matters further, the support Mattel offered Shindana had largely been in the form of retail distribution assistance, which meant that when Mattel was ready to release its own set of Black dolls, it was easy to squeeze Shindana off store shelves. Shindana ceased operation in 1983.

Coming back full circle to Healthy Roots and Naturally Perfect it quickly becomes clear how placing their efforts in historical context complicates both the business plans and the politics they advocate. The keys to Shindana’s early success and subsequent downfall were controlling manufacturing but not distribution (as well as perhaps being too trusting of their investors’ goodwill). In contrast, Healthy Roots and Naturally Perfect do not own their own means of production but have some modicum of control over distribution in the form of direct sales. But their price points make it all but impossible to find retail partners like Wal-Mart or Target, leaving boutique and specialty stores not especially known for catering to minority clientele. Ultimately, diversifying store shelves remains an obstacle both then and now, though for different reasons. And while Healthy Roots and Naturally Perfect have not sought assistance from mainstream manufacturers like Mattel, that doesn’t mean that industry leaders don’t see crowd-funding as a form of market research for determining emerging consumer trends. As my opening post about Project MC2 argued, MGA Entertainment developed a STEM-based lifestyle brand in response to the successful incursions companies like GoldieBlox had made with millennial parents through Kickstarter.

Of greater significance, perhaps, is the clear shift from a community-based form of identity politics to an individuated one. Where Shindana saw empowering African Americans by creating Black toys as intertwined with creating Black jobs, Healthy Roots and Naturally Perfect define empowerment almost exclusively in neoliberal terms as helping Black girls find self-love. Accordingly, external challenges to the Black community are overcome by individuals acquiring commodities that boost their self-confidence and teach them how to turn a social stigma into a stylish form of self-expression. If investing in Shindana was positioned as an investment in African American economic self-determination, an investment in these newer enterprises is marketed as an investment in oneself (or in one’s daughter, niece or sister), but not in a Black infrastructure that might combat institutionalized racism.

Image Credits:

1. Healthy Roots Cover Image

2. Naturally Perfect

3. Healthy Roots

4. Yelitsa Jean-Charles

5. Angelica Sweeting

6. Angelica Doll

7. Big Book of Hair

8. 70s Toy Ad

9. Shindana’s 1978 Toys (Girls)

10. Shindana’s 1978 Toys (Boys)

11. Shindana’s Success

Please feel free to comment.

- Chin, Elizabeth. “Ethnically-Correct Dolls: Toying with the Race Industry.” American Anthropologist 101:2 (June 1999): 305-321. [↩]

- see Ann DuCille’s Skin Trade for an extensive discussion. DuCille, Ann. Skin Trade. Harvard University Press, 1996. [↩]

- Ellis, Russel. “Operation Bootstrap.” People Making Places: Episodes in Participation, 1964-1984. Institute for the Study of Social Change, University of California, Berkeley. No date. http://www.russellis.net/writings/ Accessed April 4, 2016. [↩]

- see Russel Ellis’ People Making Places for an extended history of the organization. ibid. [↩]

- Quoted in Ellis. ibid. [↩]

Great article! Amazing insights! I collect dolls and I learned a lot from this.

Wow, what a great read! I’m mostly fascinated about the success of Shindana and it’s downfall because of white supremacy. I just started a black doll brand and I’m doing it on my own to avoid such bullying from big companies. They give you a slice of cake and when you’re starting to enjoy it, they take it away.

Your article is a true eye opener and also inspiration. So, thanks!