The Disney Reader

Nicholas Sammond / University of Toronto

This is the last of three essays on the creation, design, and implementation of a graduate class. In the first essay I outlined ideas for a course that would explore the relationship between textuality and space. In the previous outing I discussed its realization in a syllabus. In this essay, I review its execution as a course. Each essay approaches the topic through one of three successive lenses: the first started from Bakhtin’s notion of heteroglossia, the last one took up Lefebvre’s systematic analysis of social space, and this last essay will feature student essays that touch lightly on the troubling tension between the reading subject and the commodity object that is produced between the park and its media paratexts.

Rey Chow, “The Elusive Material, What the Dog Doesn’t Understand.” [1]

This is a story about realization.

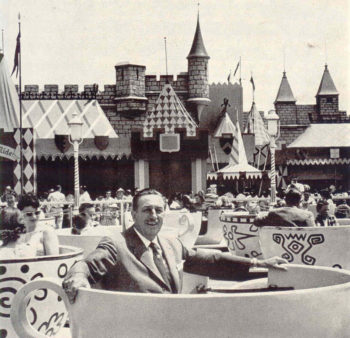

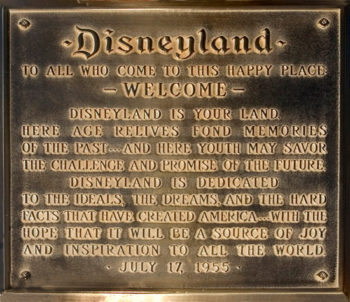

In 1974, Henri Lefebvre inveighed against what he perceived to be a spatial turn in the study of literature, the study of texts as spaces. For Lefebvre, the more urgent project for critics and scholars was the production, regulation and contestation of real social spaces. Demanding a rigorous and equally scientific response to an emerging “science of space,” he argued for the systematic analysis of the relationship between space and social subjects. Yet for some time, experiments in producing the obverse condition—the organization of social spaces as narrative texts—had been going on around the world. Disneyland, which opened on July 17, 1955, was one such experiment. It was not the first, but it was a new development in a long line of organized public/private spaces such as art and science museums (the dioramas of which Donna Haraway has called “meaning machines”), imperial expositions, and world’s fairs. [2] A heteroglossic agglomeration of paratexts, Disneyland offered a “theme,” a master narrative—Walt Disney’s vision of the world as an informative amusement—that drew upon and ostensibly corrected the nature documentary, the white hunter film, the fairy tale, the western, and science fiction in order to conform to and further Walt’s story. [3]

To what degree is it possible to impose a narrative on any given situation, especially when one is already imposed on us? When it opened in 1955, Disneyland had a narrative within which it wished to locate its visitors. It was the story of Walt Disney’s vision of the relationship between nature and culture, the past and the future…a vision of anything but the present. Indeed, that narrative, into which visitors were meant to insert themselves as subjects of and to the story that Walt was telling, was what differentiated the park from a normal amusement park. Disneyland offered a grand narrative through which to travel, and each of its paratexts, its subordinate lands, contributed to that account. The company rearticulated that narrative on its television show, via its spokesman, Walt, every week. But the space of the park itself, its organization in the larger metropolitan space of Anaheim, California and the greater Los Angeles area, as well as its place in a larger history of amusement parks, both attempted to further and resisted that story.

Each of the lands that made up Disneyland was meant to recapitulate the tidy narrative of its counterpart on the Disneyland television program, and each failed to do so in very productive ways. Far from offering the instruction in natural behavior that Disney’s True-Life Adventures delivered in theatres and on the small screen, Adventureland largely relocated the film The African Queen into a transnational landscape populated by audio-animatronic animals and people. Frontierland, far from providing instruction on the proper masculinization of an American culture feminized by WWII and Cold-War regimes of social control, was a passive and relatively inert version of its livelier ancestor, the nineteenth-century Wild West Show. Fantasyland, perhaps at the greatest distance from its promise of moral instruction for children, was little more than a traditional amusement park, the very thing that in histories of the park both the company and Walt are reported to have abjured. And Tomorrowland, unable to reproduce on the ground a fantastic narrative of scientific evolution from a prehistoric past to a futuristic tomorrow, the logic of which organized features such as Mars and Beyond (1957) or Magic Highway U.S.A. (1958), created in the park a corporatized futurespace not unlike that which organized the New York World’s Fair of 1939.

Yet even this narrative of failure is just that: a narrative. To claim that Disney failed in its goals is to accept that it actually intended to reproduce the narratives it crafted on its television program on the ground in the park. This presumes a causal relationship between Disneyland the television program and Disneyland the park that is singular, uni-directional, and coherent. To assume that the park was merely meant to be a translation of the television program overlooks a number of contingent paratexts and circumstances. There is no doubt that Disneyland was meant to advertise the park; its annual reports stated as much and its critics complained bitterly about it in terms that framed it as one of the earliest versions of the infomercial. But many of the component parts of the television show predated the park, except in its earliest conception. Disney began making the nature films in 1948, and by 1955 had already produced ten. By 1955, Disney had also produced ten animated features, its most recent being Peter Pan (1953) (Lady and the Tramp opened in 1955). [4] Disney’s venture into the western genre had begun in 1948, with its western shorts in Melody Time, and it explored the U.S.’s southern frontier in Song of the South in 1946 (as much as it would like to forget that moment). Its Davy Crockett shorts, which it would compile into feature films in 1955 and 1956, were also a mainstay of the program and the park almost simultaneously. Only in Tomorrowland would the show lag behind the park, and even there, not really. Although it was the part of the park least prepared to operate on the park’s opening day in July of 1955, and although the “science-factual” featurette Man in Space (1955) predated the park by a few months, other short features such as Mars and Beyond (1957) or Eyes in Outer Space (1959) would not appear for several years, like many animation companies, Disney had long been in the business of scientific explanation. During World War II it had produced training films for the United States Armed Forces, propaganda films such as Education for Death (1943) and Victory Through Air Power (1943), as well as public information films such as Malaria Mosquito, the Winged Scourge (1943). And, in 1946, in a precursor to its corporate partnerships in Tomorrowland, the company teamed up with Kimberly-Clark, maker of Kotex, to produce the educational short The Story of Menstruation. As it had with its True-Life Adventures, the company worked and reworked its avuncular voice of authority, one that combined gentle, self-deprecating humor aimed at the perceived follies of past humankind and a respectful and knowledgeable surety about the future, as it detailed the wonders of a science rooted in technologies supported by capitalist enterprise.

So, there are two narratives to read out of the adaptation of “The Textual Object” from its original focus on a single cinematic text to analyzing and commenting on the collation of a broader set of paratexts within and around Disneyland. The most significant is the narrative produced in the Reader assembled by the Textual Object class. Yet before that is the narrative of the class itself coming to terms with the amended project of looking at a place rather than at a film.

Asking students with very different intellectual and affective relations to Disney in general, and to its parks in particular, to produce a Reader made of paratexts to Disneyland is an imposition of narrativity on those “readers” of the park and its own paratexts. Most of the eleven graduate students enrolled in “The Textual Object” had never been to Disneyland, few had an interest in the park, and most were hard-bitten traditional film scholars whose interests lay primarily in engaging with individual film texts. So, their initial reaction to the course was one of suspicion at best, and for most active resistance. There was a brief moment of revolt in the course, when the students banded together and went on strike, refusing to engage with course readings and assignments until they had received assurance that the skills and experience that they had accrued in traditional cinema studies courses would find some outlet in the course. Of particular concern was the first of the two major assignments, an annotated paratext that analyzed the organization, operation, and implicit or explicit narrative of one of the four “lands” of Disneyland: Adventureland, Frontierland, Fantasyland, and Tomorrowland. Having never attempted to treat a place as a text, or to read that place against other texts across a range of media, quite rightly gave the students pause.

While an outright revision of the syllabus to address these concerns was out of the question, it was possible to more clearly define the parameters and expectations for this and other assignments in the course, and this led to the detailed rubrics found here. Critical reading practices do not develop ex nihilo, and the students, all of whom had been trained to read and to criticize film texts, reasonably expected more guidance in how to successfully intervene in the text of the land with which they had been asked to engage.

Once those rubrics were in place, though, the class proceeded relatively smoothly. Each week one or more students joined me in facilitating discussion on the week’s readings and film/media text, and one or more students workshopped their ideas for their particular entry in the reader. In those workshop sessions, students presented a set of paratexts and either an outline of the argument they hoped to make, or a broader set of concerns and a set of questions out of which they hoped an argument would form. After getting feedback from their peers, members of “The Textual Object” have produced Disneyland, the Reader, a complete version of which readers can access here. Below is a narrative that incorporates each of the entries produced by the members of “The Textual Object” in an overview of the park. Each link in the narrative will take readers to one of those entries.

Main Street U.S.A.

A prelude and frame to Disneyland’s four individual lands, Main Street U.S.A. orients visitors to the thematic conceit that governs Disneyland. Perhaps the street offers an echo of Marceline, Missouri, where Walt Disney spent some of his childhood years. Perhaps it intends a decorous and middle-class response to the rough-and-tumble urban amusement parks popular in Walt’s childhood, such as Coney Island. Or perhaps it resonates with the more genteel surroundings of the expositions and world’s fairs of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. This last interpretation of the thematic spine of Disneyland offers a bridge to the first of the lands that the reader/visitor can turn to, Adventureland. For one of the guiding notions of Adventureland was the celebration of a nature, and of primitive cultures, made accessible through imperial and colonial adventures.

Adventureland

Disney intended Adventureland to serve as the physical realization of its True-Life Adventure nature documentaries, which it began producing for theatrical release in 1948, long before the park’s opening in 1955. Along with its People and Places quasi-ethnographic documentaries, these nature films found in nature the logics that governed the suburban domestic imaginary of the early Cold-War United States, including a heteronormative order seemingly dictated by nature “herself.” Yet because Disney could not literally transpose the tidy narrative order of its nature and ethnographic films onto the ground, Adventureland also became a place in which visitors could inscribe new narratives. And, finally, this land looked backward to the expositions and world’s fairs of the previous century, which attempted through their own colonial narratives to produce a continuum that made conquered flora, fauna, and people roughly equivalent.

Frontierland

That narrative resonated with the ostensible logic behind Frontierland. A celebration of the westward and southerly colonial expansion of first the United Kingdom and then the United States (and much less so of the Spanish and Brazilians), Frontierland attempted to leaven the darker aspects of the Cold-War western genre, but not without a gentle nod to the violence naturalized in childhood games of “cowboys and Indians.” Frontierland also attempted to modulate the violence of the western, and to entertain adult family members no longer interested in playing cowboys and Indians, though, by staging a vaudevillian dance-hall revue at its Slue-Foot Sue’s Golden Horseshoe saloon, a show that revealed, and reveled in, the queer camp potential lurking in the masculinist genre.

Fantasyland

What is the fantasy behind Fantasyland? In Disney films, that fantasy has been one of personal realization through overcoming hardship, and growth through separation and reunion. From its earliest days, Disney has presented its animated fairy tales as “timeless,” folk expressions of eternal verities. They are anything but. Each story has a very concrete history in art, in culture, and in publishing. Pinocchio, for instance, was a story by Collodi before it was a Disney film, and that earlier version itself may trace back to medieval practices of carnival and misrule. Yet a moral message that is easy to regulate in the most controlled of cinematic forms, animation, holds the potential for anarchy, or at least resistance, when mapped into a social space such as a theme park. A tightly conceived story such as Snow White, for instance, when made into a dark ride, struggles to maintain its own narrative coherence. Fantasyland, oddly the part of Disneyland most like that which it most abjured, the amusement park, inadvertently reveals the cost of such efforts at control. Disney’s development of audio-animatronics as a version of live animation, a means of controlling unruly animals and humans by automating them, demonstrates the uncanny cost of trying to regulate the lives, or the amusement, of others.

Tomorrowland

The regulation of life through science and technology, ostensibly for the benefit of all, is the central theme of Tomorrowland. That fantasy of better living through control was given substance in the Monsanto House of the Future, which opened with the park in 1955 and closed only in 1967. Epitomizing the slogan “better living through chemistry,” the house was engineered largely from plastics, and carefully regulated its inhabitants’ relationships to each other and to the outside world. [5] Walt Disney died in 1966, while overseeing the renovations to a newer Tomorrowland he would never see. Disney (either the man or the company) would also never fully confront changes taking place in the American landscape, not of tomorrow, but of the current day. The escalation of a covert war in Southeast Asia and its resistance at home would find no place in the utopian fantasy of Tomorrowland. Nor would there be any reference to white flight, “urban renewal,” and the urban rebellions of the late 1960s and early 1970s. Indeed, in the House of the Future and its descendent attractions, the city as the central hub of social life disappeared, replaced by a fantasy of a monadic existence lived between interconnected nodes of work, home, and leisure that were indifferent to state and national borders. Yet if Disney’s commitment to being the happiest place on earth kept it firmly in the past and future, but never in the present, other utopias, such as the short-lived Star Trek series (1966-1968) attempted to address the social issues of the day through allegory. Whether Gene Roddenberry’s utopian vision was any less implicated in the systems of control and of imperial conquest that Tomorrowland celebrated is an ongoing matter for debate. Yet just as Roddenberry imagined what an ideal colonialism would look like in the 23rd century, Disney produced in the circuit of lands that made up Disneyland, paratexts to the text that it meant to be, a fantastic mid-century reinscription of better living through Cold-War hegemony.

In the iterations between being an (imperfect) subject in a story on the ground, to the passive object of the narrative’s intention—locked into a car trundling along on tracks that admit no digression, no variation—the reader/visitor to Disney’s lands is meant to, perhaps does experience that special joy in repetition so vital to the late capitalist experience, the tension between failure and success, between pleasing and failing the Great Leader, that is a visit to the happiest place on earth, Disneyland.

Image Credits

1. Theme Park Tourist

2. Mickey Mouse Schoolhouse

3. Disney Parks Blog

4. Disney Parks Blog

5. Theme Park Tourist

Please feel free to comment.

- Chow, Rey. “The Elusive Material, What the Dog Doesn’t Understand.” In Diana Coole and Samantha Frost, eds. New Materialisms: Ontology, Agency, and Politics (Durham: Duke, 2010), 227. [↩]

- Haraway, Donna. Primate Visions: Gender, Race, and Nature in the World of Modern Science (New York: Routledge, 1989), 54. [↩]

- For a discussion of heteroglossia, see Bakhtin, M.M. The Dialogic Imagination. Michael Holmquist, ed. Trans. Caryl Emerson and Michael Holmquist. (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1981). For a discussion of text and paratext, see Genette, Gérard. “Introduction to the Paratext.” New Literary History 22:2 (Spring 1991), 261-271. See also Gray, Jonathan. Show Sold Separately: Promos, Spoilers, and Other Media Paratexts (New York: New York University Press, 2010). [↩]

- Whether one should count Disney’s revue cartoons, such as Fantasia (1940), Saludos Amigos (1942), or Melody Time (1948) as features is beyond the scope of this project. They are not counted here. [↩]

- To be fair, the slogan is Dupont’s, not Monsanto’s, but no doubt both subscribe to the sentiment. [↩]