Contours of the Closet: Conceptualizing Straight / Gay on Teen TV

Wendy Peters / Nipissing University

On teen TV, the closet is often invoked when a character transgresses the boundaries of heterosexuality but does not announce with pride: “I’m gay.” In this column, I highlight narratives and dialogue from the 2010-2011 seasons of 90210 and Glee in order to explore the gendered boundaries that mark the thresholds between straight, closeted and gay. By paying attention to narrative framings of same-sex sexual activities and the closet, it is possible to see how sexuality is conceptualized differently for male and female characters. While any same-sex sexual activity gets the male teens summarily kicked out of heterosexuality, the female teens have a rather different relationship to the straight-closeted-gay logic.

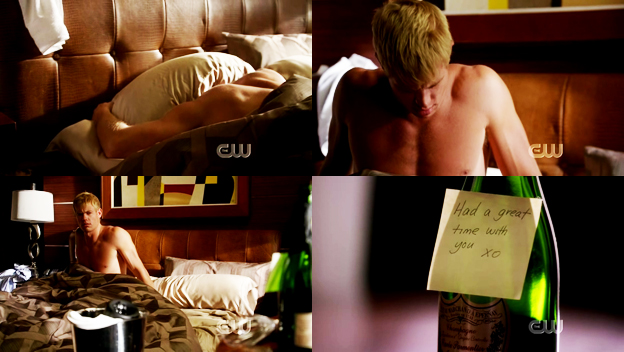

On 90210, Teddy is well established as a heterosexual “player” who has sex with many women and eventually “settles down” with one girlfriend. In the following season, Teddy has one drunken sexual encounter with an openly gay man, Ian. [1] At this point it is possible to interpret Teddy’s sexuality as straight, gay, queer, bisexual, changing or fluid, just to name a few options. After Teddy insists that he is not gay, Ian states unequivocally: “Look, just because you can’t deal with who you really are, don’t take it out on me.” With this one sentence, Ian tells Teddy and the viewers that Teddy is gay. The dialogue instructs the viewer that this single sexual experience is more meaningful than all of Teddy’s prior sexual encounters with countless numbers of women. With this one drunken sex act Teddy has transgressed the limits of heterosexuality and is narratively re-categorized as closeted until he comes out as gay later in the season.

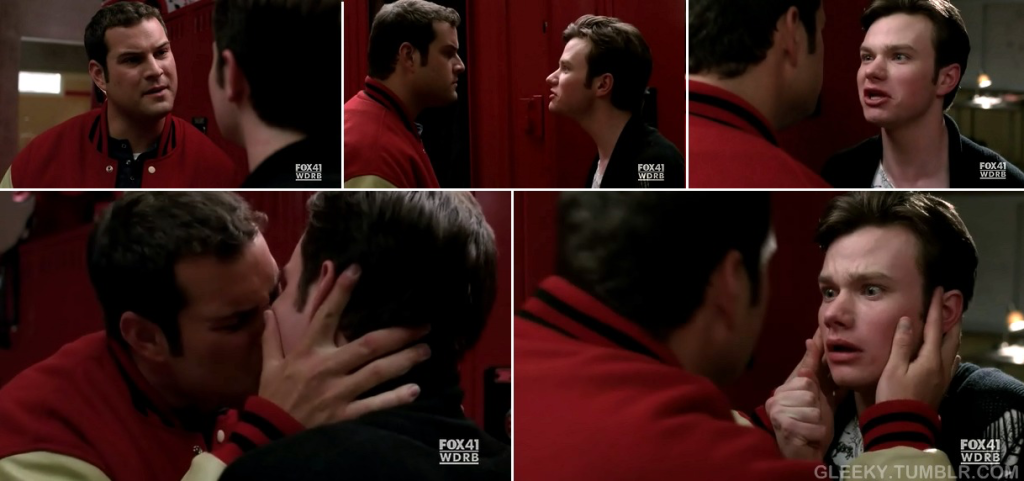

On Glee, Dave Karofsky is a football player primarily known for bullying members of the Glee Club. After a full season of threats and intimidation, Karofsky suddenly kisses Kurt, a gay teen he bullies. The kiss signals to viewers that Karofsky may not be quite as straight as we may have believed. [2] Once again, the post-kiss dialogue invokes the closet when another gay character, Blaine, tells Karofsky: “It seems like you might be a little confused and that’s totally normal. This is a very hard thing to come to terms with and you should just know that you’re not alone.” One kiss tells Kurt, Blaine and, in turn, the viewers that Karofsky needs to come to terms with the “fact” that he is really gay. Although he resists, the narrative makes it clear that Karofsky will no longer be regarded as straight by anyone “in the know.” He is narratively trapped in the closet until he comes out many seasons later. In contrast to Teddy’s active hetero-sex life on 90210, Karofsky was not shown to be interested in women prior to kissing Kurt. Yet narratively, he is presumed to be straight. Such a narrative assumption tells us a lot about how straight masculinity is imagined in mainstream popular culture. He is assumed to be heterosexual not based on romantic or sexual relationships with females, but because he is a white, masculine, homophobic “jock” who has zero sexual contact with other men. The burden of sexual proof lies entirely outside of his taken-for-granted heterosexual masculinity. One kiss ostensibly “proves” that Karofsky is gay, while no sexual evidence is required to suggest that he is straight. Unlike Teddy, Karofsky’s heterosexuality is completely unsubstantiated in the sense that he is presumed straight for over a season without visual or narrative evidence. But, like Teddy, his heterosexual masculinity is revealed to be so fragile that it takes only one impulsive kiss to come undone.

In contrast, Santana and Brittany on Glee have sex for an entire season without being characterized as lesbians or even closeted. Santana has a boyfriend, Puck, and tells Brittany: “I’m not making out with you because I’m in love with you and want to sing about making lady babies. I’m only here because Puck’s been in the slammer for about 12 hours now and I’m like a lizard. I need something warm beneath me or I can’t digest my food.” [3] While these young women have transgressed the boundaries of heterosexuality applied to their male peers, the narrative does not hold them to the same standards. There is enough room in heterosexuality for these young women to have sex with each other without dumping their boyfriends or “coming out.” In the first season, there is never any clear narrative insinuation that they must be closeted because they are “really” lesbians. For Santana to narratively shift into the closet, she tells Brittany that she has “all of these feelings” for her, but these feelings are bracketed, euphemistically, with “I can’t go to an Indigo Girls concert… I just can’t.” [4] It is this declaration of heartfelt affection—delivered well into season two—that finally causes Santana’s sexuality to be narratively reframed as lesbian, yet closeted when she says “I can’t go there” (even though she wants to). When it comes to Santana, the threshold between heterosexuality and the closet is less about having sex with Brittany and more about expressing sincere feelings of love. Meanwhile, Brittany shirks the whole straight-closeted-gay logic entirely by simply and humorously identifying as “bi-curious.” [5]

Relatedly on 90210, Adrianna—a white character who had a brief sexual relationship with a woman in a prior season—tells her straight, white, female friends that “everyone should have one lesbian experience in their lives” and they all gamely agree. [6] Once again, when sex between young feminine women is casual they are not immediately “lesbian,” even if they are having a “lesbian experience.” Heterosexuality appears to be more expansive for these young, white and feminine women as they are permitted, and at times even encouraged, to have sex with women as a matter of due course. They are not immediately regarded as closeted and do not seem to be subjected to the same assumption that any same-sex sexual activity means that they are really gay.

In part, these differing conceptualizations and boundaries mirror Western constructions of female sexuality as unimportant except in relation to reproduction and largely defined by emotional attachments, especially for white women. By this logic, these white and fair-skinned female adolescents’ sexual experiences with each other are depicted as largely inconsequential, especially when divorced from romantic love. Feminine and fair-skinned lesbians—it seems—are narratively marked by romantic love for another woman and not “simply” having sex with women. In contrast, white and masculine male sexuality is characterized as active, intentional and consequential. For these young white men to kiss or have sex with another man is shown to be so meaningful that their heterosexuality is immediately and unequivocally called into question. Arguably, their sexual transgressions against the normative Western boundaries of masculinity, heterosexuality and whiteness are so complete that they become what philosopher Michel Foucault described as another “species”—a homosexual. Further, these representations implicitly enact erasures and it seems probable that televised depictions of non-white young men, poor or working-class teens, masculine females or feminine males might reveal starkly different boundaries of heterosexuality given that each is freighted with distinct assumptions of “inherent” hypersexuality, passivity and queerness.

These narratives afford a more expansive and queer sexuality for young women while clearly restricting young men to the hetero / homo binary, with no room at all for sexual fluidity. If sexuality is conceptualized on the Kinsey scale from the exclusively heterosexual zero to the wholly homosexual six, then white and masculine male sexuality seems to occupy the decisive and restrictive end points. It is privileged as rational, agentic and consequential, while also being characterized as highly unemotional, disciplinary and limiting. In contrast, feminine and fair-skinned female sexuality languishes and takes pleasure in the expansive middle ground. It is meaningless and inconsequential in the absence of a male, yet thoroughly indulgent of a wide range of pleasures and experiences. As scholars and activists have noted, incarnations of the closet depend on the assumption that people have a “true” sexuality and tend to reify the “heterosexist assumption that individuals are straight until and unless they disclose an alternative sexual orientation.” [7] In these teen TV examples, the “true” sexuality of white and Latina women makes space for sexual activities with men and women, while marking the boundary of straight / gay as a difference characterized by romantic love. Same-sex sexual activities between feminine women are, in some sense, downplayed and discounted—dramatizing femme invisibility onscreen. In contrast, the “true” sexuality of these young, white and masculine men is dramatized as exclusively straight or gay, and the threshold between the two is largely sexual in nature. [8] The one-kiss rule that governs these young men’s sexuality sends them straight to gay with little to no regard for their thoughts and feelings, or capacity for non-binary sexualities.

Image Credits:

1. Finn and Santana on Glee

2. Teddy the Player on 90210

3. Karofsky kisses Kurt against his will

4. Brittany and Santana on Glee

5. Santana and Brittany—Lesbian

6. Adrianna and Gia on 90210

7. Girls from 90210 at the beach

Please feel free to comment.

- 90210 S03 E03 [↩]

- Glee S02 E06. [↩]

- Glee S02 E04. [↩]

- Glee S02 E15. [↩]

- Glee S02 E18. [↩]

- 90210 S03 E03. [↩]

- Ross, M. B. (2007). Beyond the closet as raceless paradigm. In E. P. Johnson & Mae G. Henderson (Eds.), Black Queer Studies: A critical anthology (162). Durham, NC: Duke University Press. [↩]

- Further analysis of how the 2010-2011 season of teen TV depicted the closet in terms of race and class can be found in: Peters, W. (2016) Bullies and Blackmail: Finding Homophobia in the Closet on Teen TV. Sexuality & Culture (iFirst, February 5 2016). [↩]

Pingback: Confusion Blog