Wicked Games, Part 2: Blood, Sex, and Pixels

Matthew Payne / University of Alabama

Peter Alilunas / University of Oregon

Case Study #2: The Birth of the ESRB

In our last column, we argued that Dungeons & Dragons became a convenient scapegoat in the 1980s for moralists seeking a ready-made crusade on which to pin their anxieties about children’s leisure time activities. Crucial to our argument was the notion of control: what happened to D&D when its creators no longer controlled how the game was perceived by the public? And, even more alarming, what happened once D&D was thought to be an actual danger to that public and therefore in need of juridical oversight?

In this column, we explore another crucial moment in the history of games and their control; namely, the formation of the Entertainment Software Ratings Board (ESRB) in 1994. This story is a predictable one in many ways. It begins with relatively simple concerns about children’s play, which escalate to moral panic status replete with a legislative response, culminating with the formation of an industry’s self-regulation mechanism designed to keep the government away and the cash registers ringing and game machines chinging.

But what is often lost in popular tellings of the ESRB’s origin story is how this particular flashpoint was, in large part, a self-inflicted wound; a by-product of an industrial arms race that sought to capture players’ hearts and dollars. In their zeal to better identify and pitch their wares to an aging community of gamers for the fourth generation of home consoles (e.g., the Sega Genesis, Super Nintendo Entertainment System, and Neo Geo) — to say nothing of trying to control that lucrative marketplace for themselves — Sega and Nintendo were blinded to how their games and marketing efforts were being perceived by an increasingly wary public. Game publishers knew their consumers were growing in numbers and aging in years. Gamers were not putting down controllers as they exited adolescence. The American public, however, was less cognizant of this demographic trend, and without a regulatory body that promised commercial transparency to parents and cultural watchdogs (or at least its veneer), the very idea of a video game containing sex and violence was anathema. After all, video games were still deemed to be children’s toys, and gameplay still unfolded primarily in private spaces, be they dimly-lit arcades at the local mall or a neighbor’s rec room. What follows is an all-too-brief historical narrative of the commercial battle for the 16-bit home console marketplace of the early 1990s and the controversy that followed. This flashpoint illustrates demonstrably that while the cocktail of blood, sex, and pixels made for good business, the resulting commercial success invited the sort of headlines and popular scrutiny that threatened a nascent but growing cultural industry with the real specter of censorship.

ROUND #1 (1985-1990)

The contentious console wars waged between Sega and Nintendo spanned three generations of home consoles (4th-6th), and lasted nearly two decades. Sega’s first entrant in the 8-bit console market, the Master System (known as the Sega Mark III in Japan), was released in North America in 1986, a year after its main competitor, the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES) was released in the United States. Although the Master System was armed with better hardware, Nintendo’s powerful marketing efforts, its expansive library of exclusive titles produced by third-party publishers, and its head-start in the marketplace ultimately proved too powerful. Sega never caught up to Nintendo during the 1980s, with sales of the NES far outpacing that of the Master System.[1] Indeed, at the height of its dominance, Nintendo controlled a whopping 83% of the home market.[2]

Nintendo’s dominance over Sega during the 1980s is evident even today in the comparative celebrity status of their respective 8-bit mascots. Sega’s monkey-like Alex Kidd, who saw his debut in 1986’s Miracle World, proved to be no competition for Nintendo’s mustachioed Mario. The plumber and his brother, Luigi, have since appeared on countless pieces of licensed merchandise while Alex Kidd has languished in relative obscurity. Sega was down but it was not out. More importantly, it learned its lessons quickly as it readied itself for the next round of competition.

ROUND #1 WINNER: Nintendo

ROUND #2 (1988-1998)

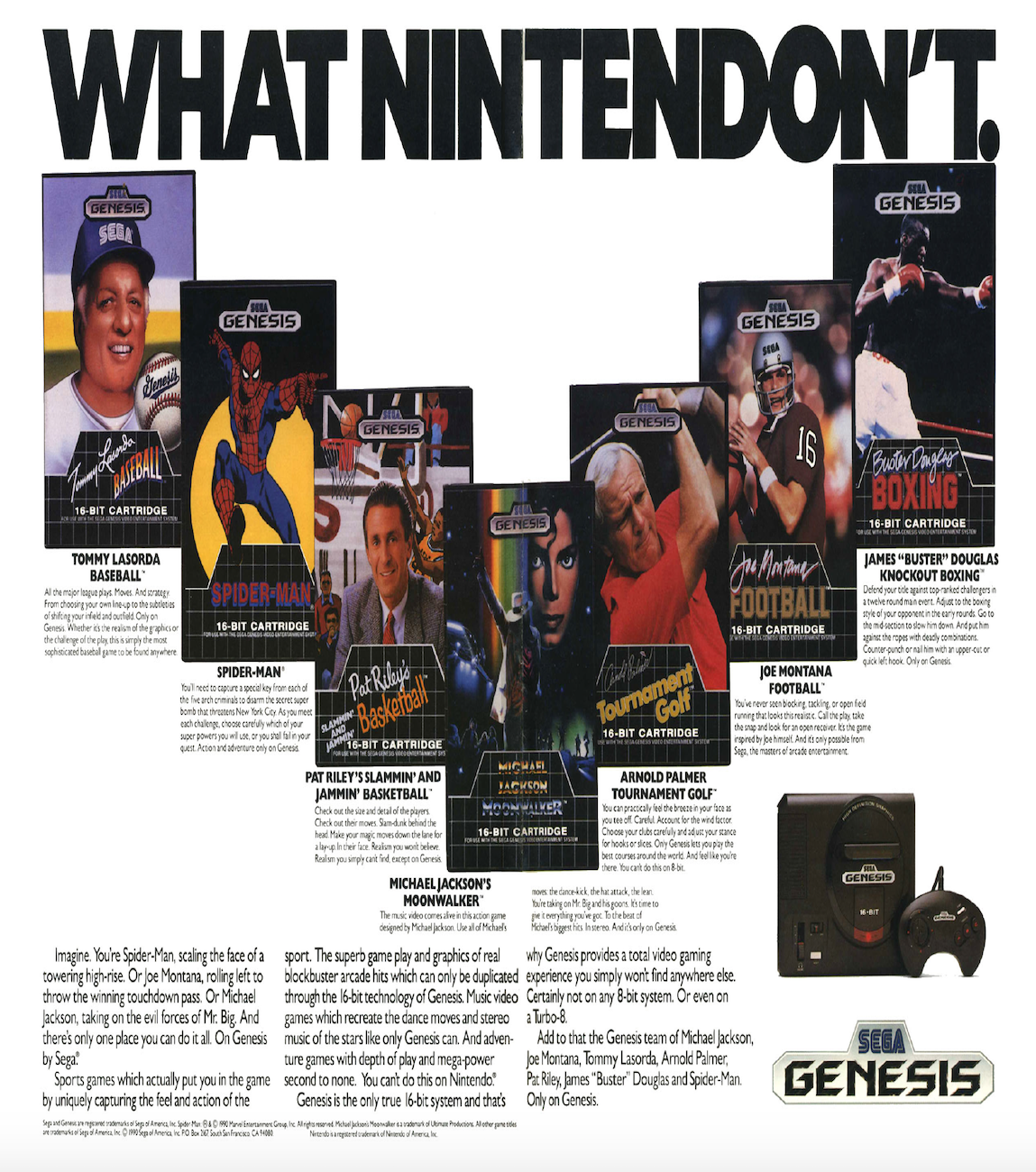

Sega wanted to beat Nintendo to the punch by being the first to release a 16-bit home console (5th generation). It also saw an opportunity to lay claim to an aging gamer demographic by appealing to teenage boys and young adults; the Genesis was something you graduated to after you were done with Nintendo’s “toys.” By specializing in sports titles (which included forging an important relationship with Electronic Arts) and by licensing popular culture properties, Sega differentiated itself from Nintendo’s more family-friendly fare. Or, as their marketing campaign memorably put it: “Sega does what Nintendon’t.” The following multi-page ad appearing in Sega Visions, the company’s response to the popular Nintendo Power magazine, illustrates the company’s thoroughgoing focus on sports and pop culture icons: Joe Montana, Buster Douglas, and Michael Jackson (to name a few).

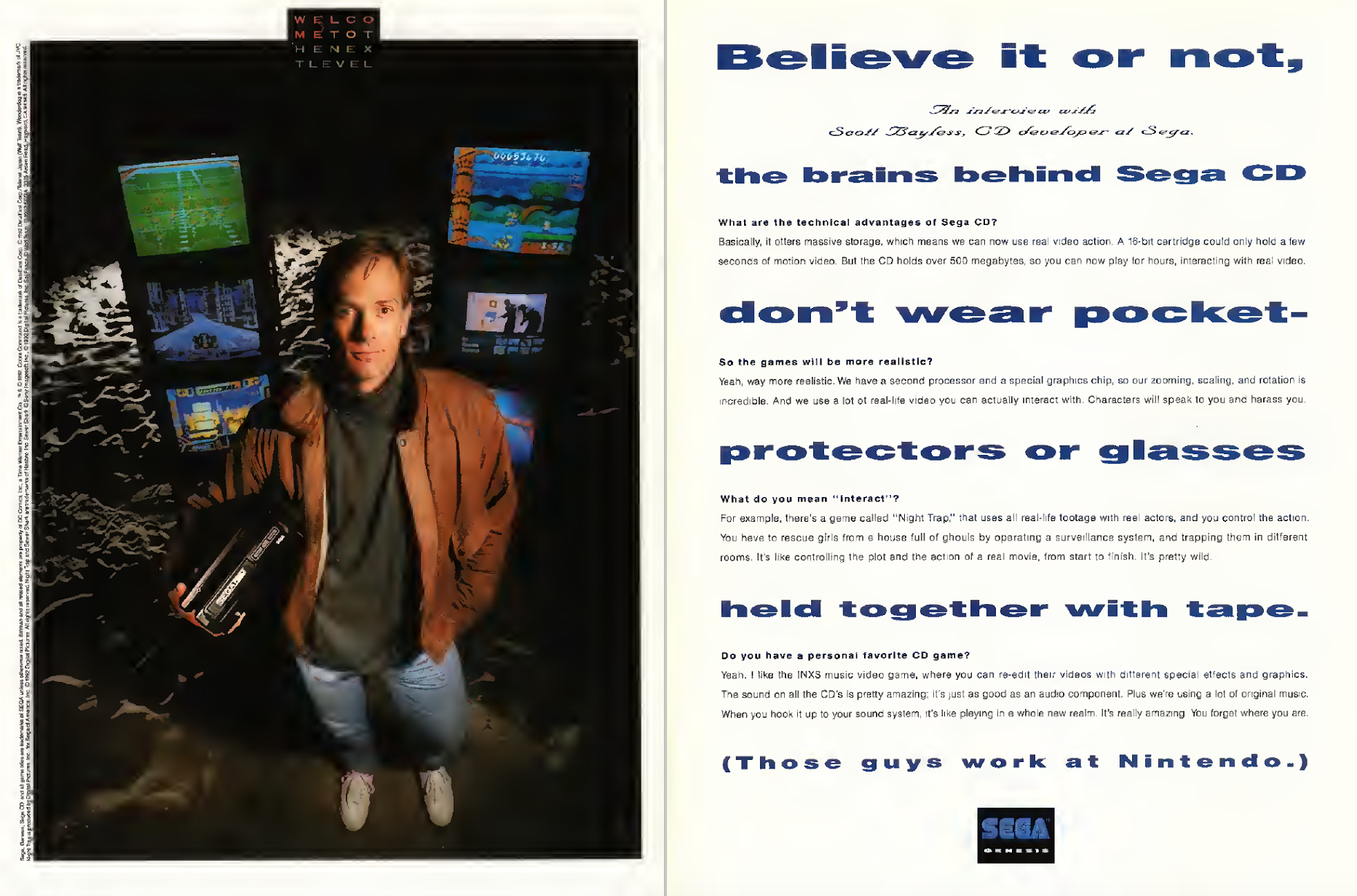

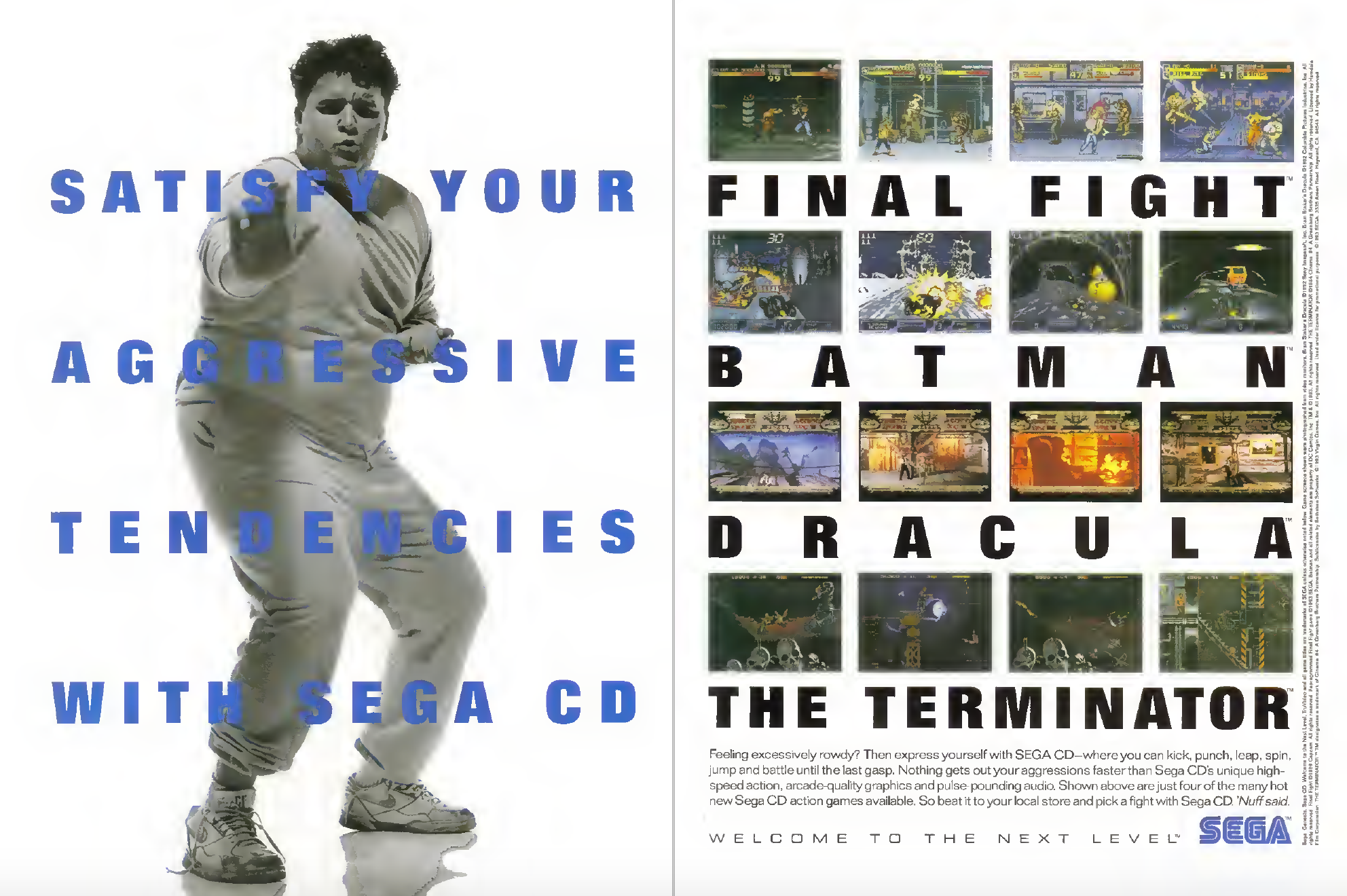

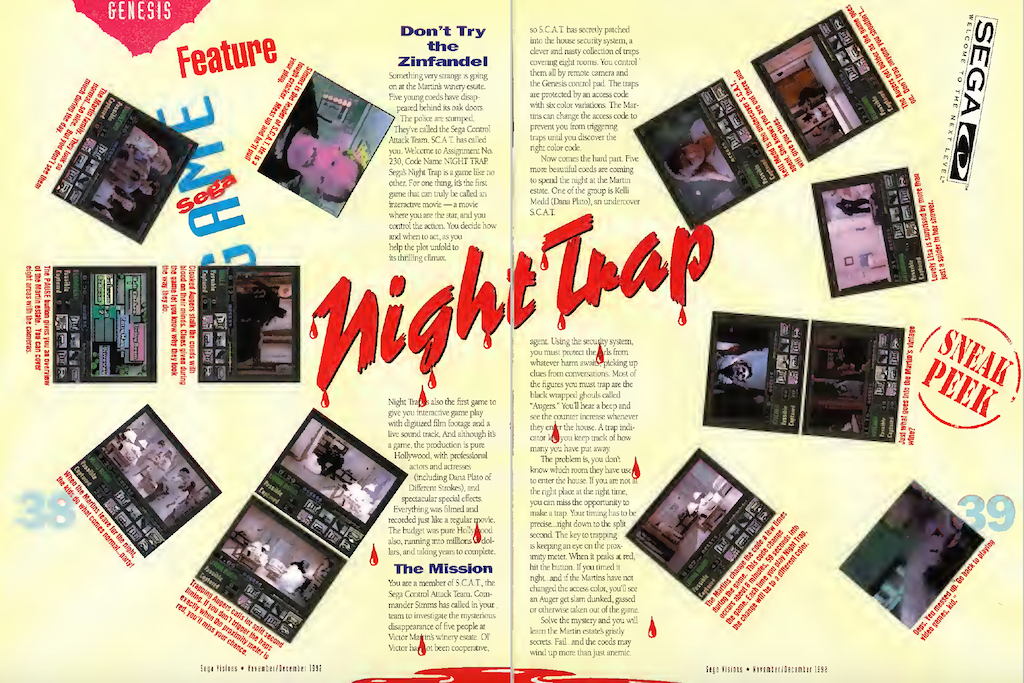

Sega also cultivated the sense of a pronounced production culture divide between the firms. The following ad, for example, takes aim at Nintendo’s “nerdy” developers. (It is worth noting that the game being advertised is the controversial Night Trap, described in “Round #3” below).

Also central to Sega’s re-branding effort for their 16-bit lineup was their new mascot, Sonic the Hedgehog. This speedy blue critter was a far cry from Sega’s previous standard-bearer, Alex Kidd, or Nintendo’s more famous Mario brothers. Sonic the Hedgehog (1991) was a platformer; but it was a platformer with an attitude.

Although the 16-bit Super NES sales figures would eventually crest and surpass that of the Sega Genesis (49 million to 29 million units sold, respectively[3]) no other company came close to dethroning the reigning video game giant during these years. Moreover, Sega’s steadfast effort to expand the content boundaries of home console titles put them in direct opposition to Nintendo in the marketplace and, eventually, in opposition in the halls of congress.

ROUND #2 WINNER: Sega

ROUND 3: Sega vs. Nintendo … vs. Congress

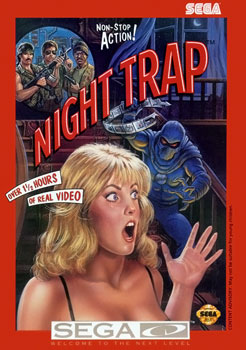

Hoping to press their momentary advantage, Sega released the Sega CD in 1992, a CD-Rom peripheral for the Genesis. With the CD’s additional storage space, game producers could package far more material into a game including full motion video (FMV) starring human actors. The pursuit of “realism” quickly became the center of attention. Among the early “interactive movie” games was Night Trap (1992), a schlocky horror title where players save young women at a slumber party from a group of fangless vampires. Of particular interest to panicked cultural critics was a scene depicting a woman in a nightgown being captured in a bathroom. Despite such apparently scandalous subject matter, the game, while moderately popular (especially in the UK), was not necessarily a smash hit. At least, not until it became the one half of an ensuing moral panic around sex, blood, and video games.

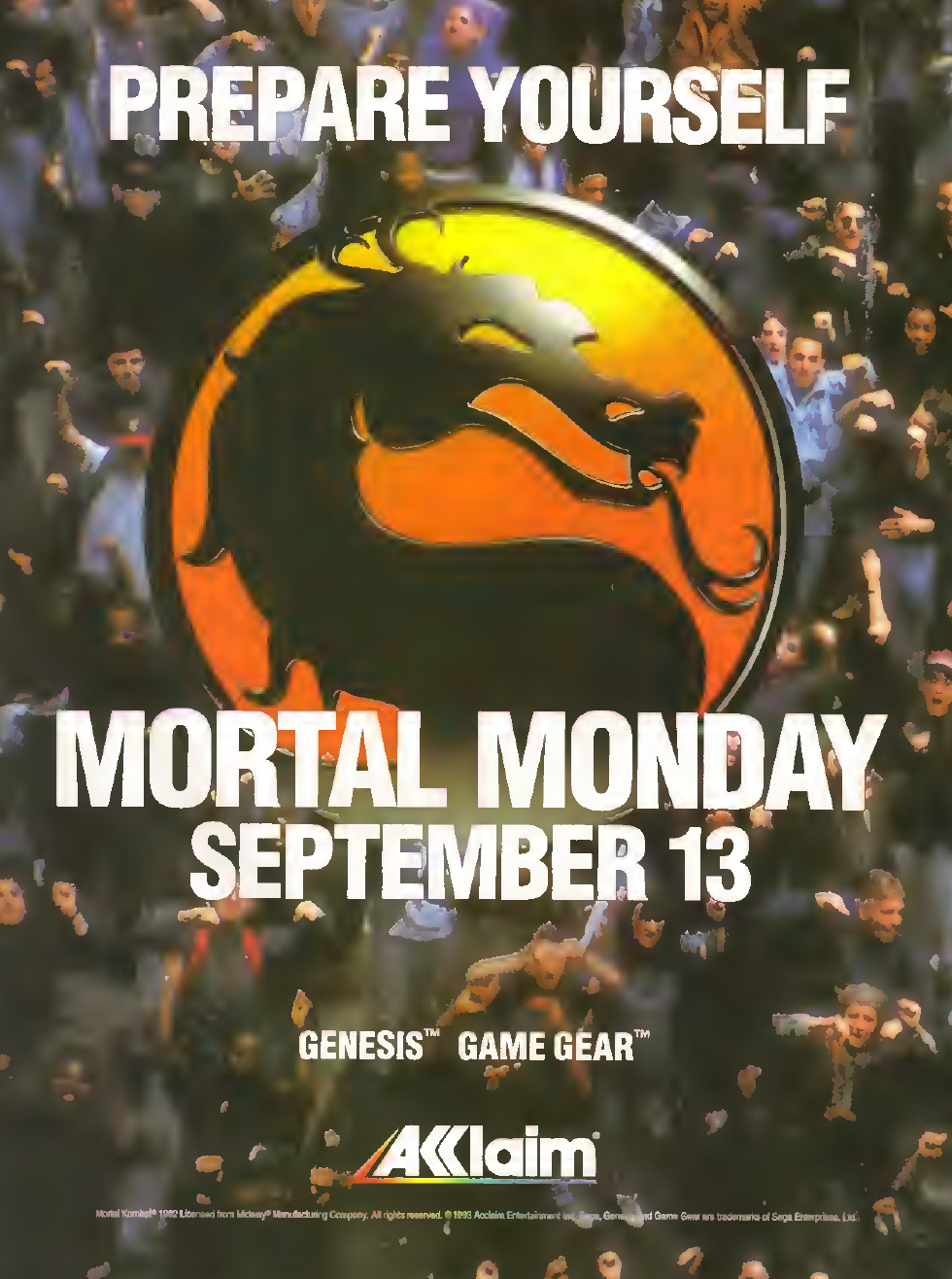

The other half of the panic was Midway Games’ Mortal Kombat, also released in 1992, which was designed to compete for gamers’ quarters against Capcom’s wildly successful 2D brawler, Street Fighter II (1991). But whereas Street Fighter II was stocked with cartoonish combatants, Mortal Kombat starred digitized human fighters who bled and did grave bodily injury to one another. The game was a smash hit, and both Nintendo and Sega desperately wanted the game for their 16-bit consoles and portable devices (i.e., the Nintendo Gameboy and Sega Game Gear). Following a tremendously successful “Mortal Monday” release event preceded by a $10 million marketing effort that included primetime TV spots, magazine advertisements, promotional trailers in 1,600 movie theaters, Mortal Kombat made millions of dollars and became a cultural phenomenon.[4]

Despite their different degrees of success, Mortal Kombat and Night Trap did share one common feature: the capacity of their increased “realism” to inspire cultural panic. In June 1993 Sega, sensing the rising anxiety surrounding the games, assembled experts in education, psychology, and sociology into a “Videogame Rating Council” (VRC). The company’s games were slotted into one of three categories: GA for general audiences, MA-13 for mature audiences, and MA-17 for adults. The move, which only rated Sega’s games, did little to quell the growing panic that the screen violence would somehow inspire worldly violence. By late in the year, Senators Joseph Lieberman (D-Conn.) and Herb Kohl (D-Wis.) initiated legislation that would force the game industry to implement a ratings system within one year or face government intervention.

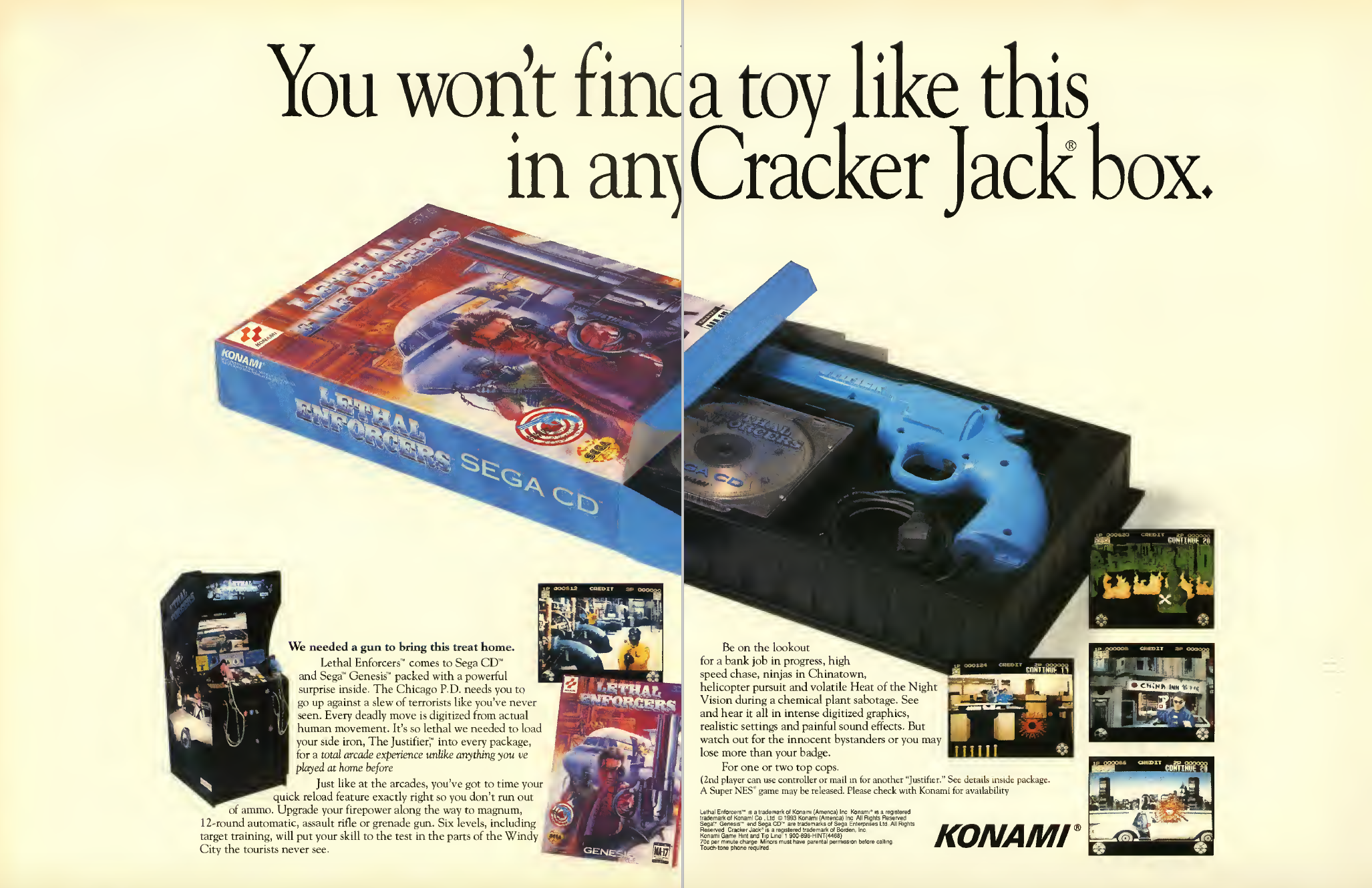

Hearings on the bill were ugly: Lieberman showed clips from Night Trap, wielded the plastic gun shipped with Sega’s Lethal Enforcers game, and played a Sega commercial that he claimed was targeting children to play Mortal Kombat. The assembled panel of industry executives surely could not have been pleased to hear Lieberman’s inflammatory rhetoric, particularly such statements as, “These games teach a child to enjoy inflicting torture.”[5] It was shades of D&D all over again: the fear of blurring the lines between children, adults, and games.

By that point, though, the industry was already scrambling hard to ease the legislative pain and shift the discourse away from potential harm to one of self-control. Eighteen software companies and the Video Software Dealers Association formed a coalition in early December 1993 and announced they would create a ratings system. “Parents have every right to know and understand what their kids are getting,” said Electronic Arts executive Jeanne Golly in a press conference outside the hearings; such self-serving statements may have contradicted the narratives at play in commercials like the one for Sega shown by Lieberman, but they clearly fit the requirement that something was “being done” about the problem.[6] It was certainly not a moment too soon for the industry: by mid-December, Toys ‘R’ Us and other retailers announced they would stop selling Night Trap, pouring fuel on the panic fire (and, of course, making the game even more taboo and thus desirable).[7] In early January, Sega threw in the towel and pulled the game from the market in order to “revise” it. Lieberman called the announcement a “small victory” on a larger road to a less violent society.[8]

The game industry didn’t wait for things to get worse. It was during meetings at the Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas in early January that the Entertainment Software Ratings Board (ESRB) was born. The self-regulatory agency, created and managed by a coalition of software companies, offers guidelines, ratings, and strategies to convey information to retailers and parents. Moreover, and most importantly, they also ensure nervous politicians stay out of game stores and living rooms. Ultimately, while Lieberman and Kohl might have declared some sort of victory, it was the game designers and retailers that survived the battles to emerge with deeper pockets and an “official” mechanism in place to placate those who feared adult games were encroaching on children’s play.

ROUND #3 WINNER: Sega, Nintendo, and the Industry itself…

Conclusion

Once the ESRB was established, Sega’s VRC folded and disappeared, as it had become an unnecessary redundancy. The result in the years since has been very nearly a replication of the ratings system overseen by the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA), which serves a similar purpose: maintain an “official,” internal mechanism to regulate content (one that promises to control the spectatorial and play behavior of children) and which will keep the threat of government interventions at a distance.[9] This regulatory moment was inevitable, perhaps even overdue, for the game industry. The combination of aging consumers, technological advancement, and creative and commercial investments meant boundaries of cultural acceptability would be pushed, eventually, into the ever-present and always on standby anxiety around “the children.”

While initially resistant, the game industry came to accept and embrace the economic necessity of creating a self-regulatory body. It was a strategy that the creators of D&D and other tabletop role-playing games certainly could have utilized to mitigate the moral panic that swept across the cultural landscape during a previous era. Despite their ability to keep politicians and anxious publics at bay, such bodies also inevitably have a creative chilling effect in that they lead first to distribution suppression. No major theater chains will play NC17-rated films, for example, just as no large-scale retailers will sell “Adults Only”-rated games, even though these are both “official” ratings categories. This means, obviously, that very few creators are willing to create content that will lead to such ratings. Even with such internal suppressions, though, the overall result for self-regulated industries is economic stability and discursive control, not to mention a mechanism for foreclosing episodes that might lead to public outcry, Congressional response, and moral panics. Ultimately, in exchange for imposing creative limitations, the ESRB helped guarantee a predictable marketplace and economic return on investment.

Despite the clear intentions of regulatory bodies such as the ESRB to contain the industry in a tidy, controversy-free package, ruptures are also predictable and unavoidable. The nature of regulation is that boundary-crossing is not only inevitable, but even, ironically, occasionally necessary. It allows regulators to keep the boundaries clearly defined and supported by a vigilant and wary public. In our third, and final, column, we will examine an example of just such a prominent and inevitable rupture: the “Hot Coffee” modification of the 2004 game Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas that permitted users to see a sexually graphic sequence hidden by the game’s creators. The predictable panic that followed was rooted in anxieties about visibility, dependability, and trustworthiness: what happens when self-regulatory mechanisms designed to keep play transparent, such as the ESRB, fail to do their critical job? The fear of “dangerous play” is always lurking in the shadows, like the monsters in D&D’s mazes or the escalation of graphic content during the arms race of the fourth-generation console wars. In our concluding column, we continue to explore these tensions, and argue that the cycle of panics, regulations, and ruptures are an inevitable, predictable, and useful way of understanding how gameplay is produced and consumed.

Image Credits:

1. Entertainment Software Rating Board (ESRB) Ratings

2. The Sega Master System, circa 1985

3. Sega’s first company mascot, Alex Kidd

4. Sega’s famous anti-Nintendo marketing campaign (Author’s screen grab from Sega Visions Vol. 1, Issue 1. June/July 1990 pp. 25-27.)

5. Sega targets Nintendo’s nerdy designers (Author’s Screen grab from Sega Visions Nov/Dec 1992, pp 6-7.)

6. Sonic breaks the fourth-wall with his finger-wagging and toe-tapping attitude.

7. Sega promises catharsis to its aging core demo (Authors screen grab from Sega Visions, Aug/Sept 1993, pp. 20-21.)

8. Sega’s original cover art for Night Trap (1992)

9. Night Trap‘s preview complete with dripping blood (Author’s screen grab from Sega Visions, Nov/Dec 1992, pp 38-39.)

10. “Mortal Monday” print ad for Mortal Kombat‘s September 1993 console release (Author’s screen grab from Sega Visions, Aug/Sept 1993, p. 3)

11. Lethal Enforcers was the target of congressional scrutiny (Author’s screen grab from Electronic Games, Vol. 2, Issue 4. Jan. 1994)

- Sega did have better success in Europe, where the Master System outsold the NES. [↩]

- Douglas C. McGill, “Nintendo Scores Big,” New York Times, 4 December 1988. http://www.nytimes.com/1988/12/04/business/nintendo-scores-big.html?sec=&spon=&pagewanted=2. [↩]

- IGN, “Genesis vs. SNES: By the Numbers,” 20 March 2009, http://www.ign.com/articles/2009/03/20/genesis-vs-snes-by-the-numbers. [↩]

- Lindsey Gruson, “Video Violence: It’s Hot! It’s Mortal! It’s Kombat!; Teen-Agers Eagerly Await Electronic Carnage While Adults Debate Message Being Sent,” New York Times, 16 September 1993, B8. http://www.nytimes.com/1993/09/16/nyregion/video-violence-it-s-hot-it-s-mortal-it-s-kombat-teen-agers-eagerly-await.html [↩]

- John Burgess, “Video Game Firms Yield on Ratings,” Washington Post 10 December 1993: F1. [↩]

- John Burgess, “Video Game Firms Yield on Ratings,” Washington Post 10 December 1993: F1. [↩]

- Tom Redburn, “Toys ‘R’ Us Stops Selling a Violent Video Game,” New York Times 17 December 1993, B1. [↩]

- John Burgess, “Sega to Withdraw, Revise ‘Night Trap,’” Washington Post 11 January 1994: D5. [↩]

- For more on the history of movie regulation, see: Richard Maltby, “The Production Code and the Hays Office,” in Grand Design–Hollywood as a Modern Business Enterprise, 1930-1939, ed. Tino Balio (New York: Scribner, 1993). [↩]

Pingback: Wicked Games, Part 3: Caution — Contents May Be Hot… and Hidden Matthew Payne / University of AlabamaPeter Alilunas / University of Oregon – Flow