Textual Object

Nicholas Sammond / University of Toronto

This is the second of three essays on the creation, design, and implementation of a graduate class. In the previous outing I outlined ideas for a course that would explore the relationship between textuality and space. In this essay I will discuss its realization in a syllabus. In the final essay, I will review its execution as a course. Each essay approaches the topic through one of three successive lenses: the first started from Bakhtin’s notion of heteroglossia, this one takes up Lefebvre’s systematic analysis of social space, and the last will consider new materialism’s troubling of the category of the reading subject.

“…the Text achieves, if not the transparence of social relations, that at least of language relations: the Text is that space where no language has a hold over any other, where languages circulate (keeping the circular sense of the term).”

Roland Barthes, “From Work to Text”1

“We are forever hearing about the space of this and/or the space of that: about literary space, ideological spaces, the space of the dream, psychoanalytic topologies, and so on and so forth. Conspicuous by its absence from supposedly fundamental epistemological studies is not only the idea ‘man,’ but also that of space—the fact that ‘space’ is mentioned on every page notwithstanding.

Henri Lefebvre, The Production of Space2

This is a story about implementation.

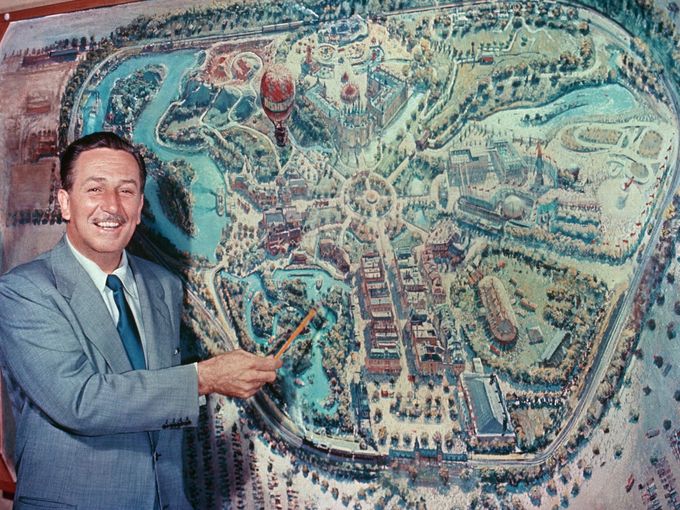

To call a place like Disneyland a text is a conceit. It offers the possibility of reading in the designed landscape of the theme park a narrative, or even a collation of narratives that then form a master narrative. The term “master” is appropriate: one reading of the larger narrative of Disneyland is that it reproduces the ideal fantasy of Walt Disney’s life. From the early 1930s on, Disney’s public relations described Walt as the guiding spirit behind everything the company made, and it suggested that his formation as the ideal Middle American was transmuted in its products and transmitted to the children who consumed them. Main Street U.S.A. reproduced Walt’s small-town childhood in the Midwest; Adventureland featured his deep connection with animals, his sense of their primal importance; Frontierland celebrated the settler spirit of Middle America; Fantasyland manifested Walt’s childlike love of fairy tales; and Tomorrowland celebrated him as an inventor invested in technology’s promise of a better future. Each land was a text unto itself; together they formed the larger text of Disney-land, the place that manifested the life story of the man.

Yet the conceit of Disneyland as text runs the risk of occluding the very real spatial relations it imagines and attempts to create. A book, movie, or television program is a self-contained entity, populated by characters who perform a free will they don’t actually have. In Disneyland, however well managed it may be, people do unpredictable things, take away unexpected messages. This is exactly the complaint and the concern of the sociologist Henri Lefebvre. Imagining a spatiality in mediated texts, or ascribing textuality to actual places, runs the risk of obscuring the complex ways in which actual spaces themselves attempt to organize, regulate, and understand complex social practices and relations. This is the central tension and core idea of the graduate course “The Textual Object: Disneyland”: that the ideals produced in the television program Disneyland—and in its subsidiary segments Adventureland, Frontierland, Fantasyland, and Tomorrowland—were nearly impossible to translate into the actual spaces meant to represent them in Anaheim, California. And it is that ongoing tension, that contradiction, which makes Disneyland such a useful text to read, such a valuable space to analyze.

The opening sections of the syllabus examine the putative origins of Disneyland: its precursors were the amusement parks of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, many of them outgrowths of the world expositions that were organized during the same period. I say “putative” because Disney’s own history, produced by the company itself, as well as by the chroniclers of the company and its eponymous founder, have produced a story that is often very speculative and contradictory. In the case of Disneyland, there is a question as to whether the park is more indebted to Coney Island, Denmark’s Tivoli Gardens, or to the 1939 New York World’s Fair. Rather than to try to settle that question of fact, it’s more productive to note the ways in which the company promoted Disneyland as like or unlike any of those places, which makes each of them antecedent, either as an exemplar or as a cautionary tale. Disney created Disneyland as much as an antidote to a raucous, slightly ribald, perhaps dangerous, and dirty place like Coney Island’s Luna Park in its heyday as it was an homage to the genteel pleasures of the Tivoli Gardens or the technological wonders of the 1939 New York World’s Fair.

Amusement parks owed a bit to the midways of those expositions, many of which featured thrill rides, freak shows, games of chance, exotic dancers, and drinking. As Lauren Rabinovitz points out, although they may have been inspired by expositions, many amusement parks grew out of public or semipublic gardens and swimming parks.3 In some cases, as urban railways began extending streetcar lines to the edges of cities, they sought to attract riders by putting amusement parks at their further reaches, then stocking them with paying attractions. For example, the founder of Steeplechase Park and Luna Park, George Tilyou, was inspired by the 1893 Chicago Exposition and saw in it a moneymaker. Although some amusement parks were genteel and moderate, appealing to a burgeoning industrial middle class, the general association, and certainly Disney’s sense of the amusement park, is that they were gritty, loud, extensions of rapidly mechanizing urban landscapes, celebrating (as Rabinovitz notes) the tension, danger, excitement, and titillation that the modern urban environment offered. It was for this reason, perhaps, that Disney welcomed visitors to its park via the decidedly small-town Main Street U.S.A.

Main Street U.S.A., the entrance and spine of Disneyland, was presented as a faithful recreation of a “typical” small American town, circa 1900, and its shops as the precursors of the modern businesses—Kodak, Carnation, Upjohn—that ran them as concessions. (Even Main Street had conflicting origin stories. Some have claimed that it was modeled after Walt Disney’s childhood home of Marceline, Missouri; others have suggested that it resembles Fort Collins, Colorado, the home town of its principal designer; the company disavows both stories.) Performing a spectacular fantasy of ideal small town life—with marching bands, circus parades, and processions of “horseless carriages”—Main Street also was meant to be an accurate reproduction of that life, hence educational. Likewise, Adventureland, Frontierland, Fantasyland, and Tomorrowland each, in varying degrees, also framed spectacle as an opportunity for edification.

The expositions on which Disneyland modeled itself as educational began with the rise of industrial capitalism in the mid-nineteenth century. Though the grandest and best remembered of these was the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893, in Chicago, through the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis and the 1915 San Francisco Pan Pacific Exposition each has its echoes in Anaheim.4 Each of these expositions celebrated the emergence of the United States as an imperial power, and they did so through an ingathering of commodities from newly acquired territories—commodities which included the “native” populations of those lands. Recreations of whole villages, with inhabitants, were very popular at the expositions, producing a sense of uplift and education, and counterposing life in the United States as civilized in comparison to the savagery of conquered peoples. These exhibits were distant relatives of the exhibits in P.T. Barnum’s American Museum and Buffalo Bill’s Wild West (strangely later recreated in Disneyland Paris), but they differed in that they seemed to eschew sensationalism in favor of a patina of scholarship and the potential to educate. (Authenticity was fungible in these exhibits. The great African American Broadway performers George Walker and Bert Williams reported that they got their start when a “Zulu show” scheduled to open in San Francisco was delayed an local men were recruited as stand-in natives.)5

Disney conceived of Adventureland as the physical realization of its True-Life Adventures (1948-1960), nature films which it first created for theatrical release and later featured in rotation on the Disneyland television show. With titles such as Bear Country (1953), White Wilderness (1958), and Nature’s Half Acre (1951), most focused on specific biomes or regions, stitching together a series of vignettes about specific species or about relationships between species. The company advertised, and tried to hire, heterosexual couples to capture these scenes, a trope which expanded upon the popular “white hunter” genre of the 1930s-1950s—realized in films such as Chang (Cooper 1927), or the Frank Buck films such as Bring ‘Em Back Alive (Elliott 1932) or Tiger Fangs (Newfield 1943).6 Disney’s choice to feature married couples as cinematographers updated that trope by creating a seeming symmetry between the observer and the observed: wherever possible, Disney mapped human gender relations (as it understood them) onto a wide range of species, purporting to offer a glimpse into the lives of natural “families.” In this, the company participated in and amplified the popular neo-Freudianism of the postwar years—espoused in popular literature by the likes of Benjamin Spock, Margaret Mead, Erik Erikson, and Erich Fromm, which (with variations) argued that the social discontents that had produced the extremes of WWII, embodied in fascism and state communism, and the social upheaval caused by the war itself (including the trauma to its male soldiers) could best be addressed through psychoanalytic means. This approach promised to address neurosis in veterans, sexual “perversion” (homosexuality, the social precariousness of which might make gay men and women vulnerable to communist blackmail and subversion), and “momism” (the problem of wartime wives and mothers having accumulated excess social and domestic power in the absence of male authority).7 At the level of popular culture for children and families, this meant modeling “natural” gender relations in which the proper social roles for each (and there were only two) were clearly delineated. The True-Life Adventures, and Adventureland, provided examples of a natural order meant to mirror visiting happy families.

This kind of gender mapping was easy to do in its nature films, which Disney circulated in theaters and on the Disneyland television show. On the ground in the park, however, the fine grained relations that closeups, music, narration, and editing could create were nearly impossible to reproduce. Although animatronic versions of large animals such as hippos, giraffes, and elephants could be arranged in heteronormative familial groupings, recreating the suburban home in the “jungle,” scaling that fantasy up and down the chain of being was impossible. Instead, Adventureland in the park hearkened back to adventure rides in amusement parks, and gestured toward the world of the white hunter/naturalist more than to the scientific researcher. When the park opened in 1955, Adventureland featured the Jungle Cruise ride, a nod to the True-Life Adventures’ The African Lion (1955), with a little of The African Queen (1951) and Trader Mickey (1932) thrown in. Visitors to the park rode in riverboats reminiscent of the African Queen and a pilot in a pith helmet and khakis provided the narrative as they meandered through a quasi-African landscape, menaced by animatronic crocodiles and hippos (one of which the guide shoots). In 1962, Disney added the Swiss Family Robinson Treehouse to Adventureland and in 1963 opened the Enchanted Tiki Room. So, the tidy gendering of nature that True-Life Adventures performed were replaced on the ground by the gendered performances of the families themselves.

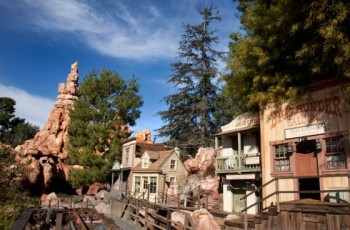

One other feature of the Jungle Cruise ride was that menacing animatronic natives peered out of the underbrush, and a pile of human bones in a native village hinted at the dangers of cannibalism, which had been so prominently displayed in Trader Mickey. The colonial fantasy hinted at in Adventureland was the organizing principle in Frontierland, shifted from the Dark Continent to the American West of the 19th century. Ostensibly organized around the changing modes of transportation used to traverse the continent—from Conestoga wagons, to paddle-wheel steamers, to stage coaches, to a railroad that took visitors there from Main Street—Frontierland celebrated conquest. Whether riding pack mules or in Mike Fink’s keel boats, visitors relived the “taming” of the wilderness (and its peoples) by European settlers moving westward. Again, regulating the narrative proved challenging, with the traditional oater battle between cowboys and Indians modulated by an Indian village in which Native American performers presented arts, culture, and dance to curious visitors. (Frontierland also featured a native village viewed from several rides, in which one lone human performer shared a fire circle with fellow animatronic natives.) Visitors to Frontierland could also board the Mark Twain Riverboat and travel to Tom Sawyer Island. In 1966 Disney added New Orleans Square, and in 1967 the Pirates of the Caribbean ride, and with that expanded the representation of the colonial experience southward, and if the “red man” of the western frontier was represented through gunfights, dances, and teepees, the colonial subject of Frontierland’s southern reaches was represented through piracy, voodoo, and more jungle-theming.

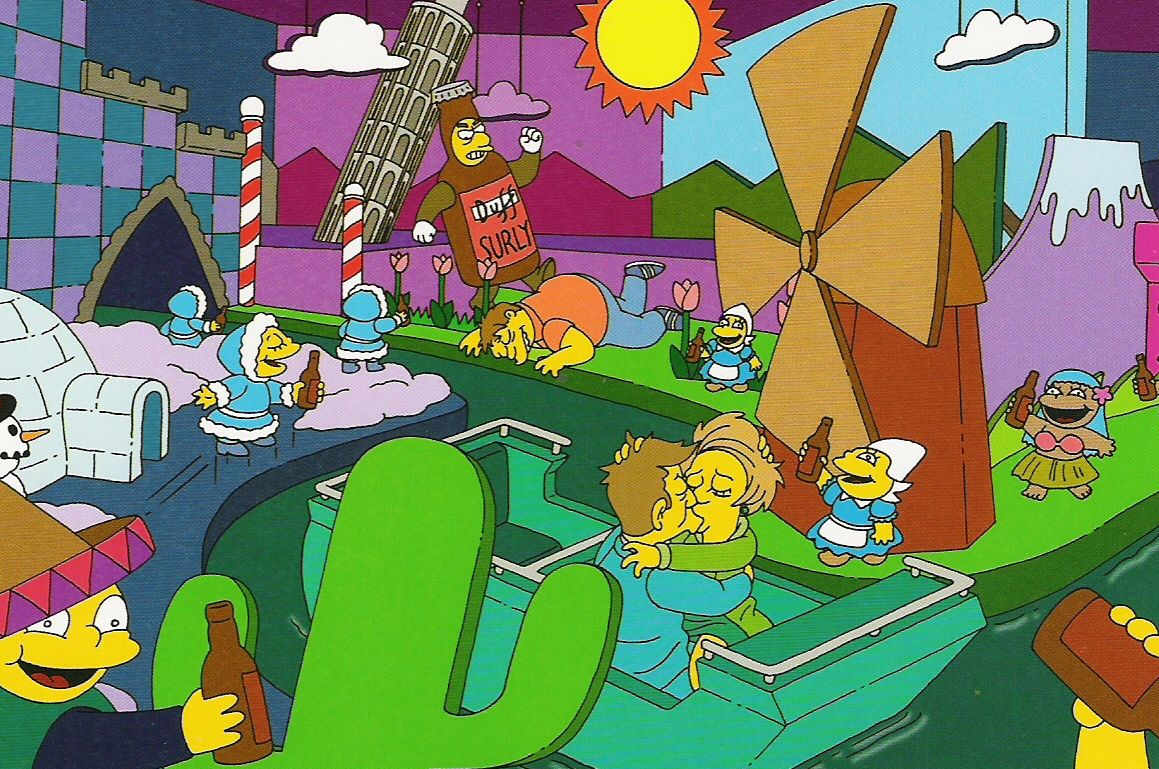

Fantasyland continued Disney’s negotiation of the contradictions between ideals it could realize in its animation and live-action film and the messy complications of unspooling a coherent narrative on the ground in the park. Walt’s dedication plaque for Fantasyland reads, in part, “In this timeless land of enchantment the age of chivalry, magic and make-believe are reborn and fairy tales come true.” The notion that the fairy tales that Disney animated represented eternal truths, rather than the work of authors like Charles Perrault, the Brothers Grimm, Carlo Collodi or J.M. Barrie, was important to the Disney mythos. But creating an environment of “timelessness” in Anaheim, California, circa 1955, proved a challenge. So, this part of the park, more than the other lands, most resembled the amusement parks of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Disney’s animated feature films built narratives of very gendered self-realization around the affective push/pull of separation anxiety (experienced by parents and children alike). On the ground, those devices faded. After visitors entered through Snow White’s Castle (the “happily ever after” of that story), Fantasyland featured rides such as the Casey Jr. Circus Train (a nod to Dumbo) and appropriately, the aerial carousel Dumbo the Flying Elephant, as well as the King Arthur Carrousel, The Mad Tea Party saucer ride, Mr. Toad’s Wild Ride, Peter Pan’s Flight and Snow White’s Scary Adventures. All of the rides related thematically to Disney movies, but all were for the most part standard amusement park rides. Of later additions, the most notable was It’s a Small World (1966), Disney’s nod to internationalism whose ominous overtones were hilariously sent up in an episode of The Simpsons set in Duff Gardens.

Missing in all of those rides was Disney’s heavy investment in, and contribution, the regulation of gender normativity in 1950s American culture. Parents raising children via the neo-Freudian counsel of Dr. Benjamin Spock or through the headier ideas of social critic/practitioners such as Erik Erikson were warned that the proper performance of gender roles by both mothers and fathers was key to restoring a social order badly warped by the privations of World War II. For men this meant providing a strong, steady, and regular manly presence in the home. Little boys needed a clear masculine role model to imitate, struggle with, and grow into; little girls needed a strong, supportive male love object to outgrow, preparing them for the well-adjusted boys and men they would eventually choose to reproduce an ideal American life. For women it meant conceding to their husbands the masculine control of the home that they had by necessity taken during WWII, acting as loving and supportive mothers, yet only as representatives of their husbands in their day to day absences, second to them in authority at all other times. Couples, finally, had to perform clearly what heterosexual love and desire looked like, the courtship of women by men and the yielding of women to men, as part of the natural order. Disney’s fairy tales, which often featured absent parents, served as cautionary tales in which the abandoned child had to overcome peril and challenge to become an integrated member of society, and as comforting stories about the resilience of children who evinced the inherent power of heteronormative behavior. That spinning mechanical teacups and carousels didn’t signal that clearly was a secondary problem; the visitors could accomplish that work by associating the ride with its animated antecedent.

One possible positive outcome for this careful gender modeling was Tomorrowland, a utopian future world in which technology laid to rest the problems of the midcentury United States. (Appropriately, a skyway tram system linked Fantasyland to Tomorrowland.) Perhaps appropriately, Tomorrowland was the least developed part of Disneyland when the park opened in July of 1955, and perhaps a harbinger of the future we now occupy, most of the rides were sponsored by outside corporations. TWA paid for the Ride to the Moon; Richland Oil sponsored the Autopia ride; the Dutch Boy Paint Gallery was self-explanatory; and American Motors sponsored the cinema-in-the-round Circarama. Monsanto sponsored a Hall of Chemistry, then expanded its offerings in 1957 with the Monsanto House of the Future. In 1959 Disney added its famous and long-anticipated Monorail (also mocked on The Simpsons), its Submarine ride, and The Matterhorn, which was eventually moved to Fantasyland since there was little futuristic about it.

Whether by design or by economic necessity, Tomorrowland boomeranged visitors from the pre-capitalist past of Fantasyland into an inherently corporatist future. Disney’s televised version of Tomorrowland, on Disneyland, while it still celebrated technology, eschewed the sponsorship angle. (Given the tensions around sponsorship, advertising and broadcasting in the late 1950s, this shouldn’t be surprising.) Disney’s “science factual” films, such as Man in Space (1955), Mars and Beyond (1957), Our Friend the Atom (1957), and Magic Highway U.S.A. (1958), were each about an hour long, and each presented an evolutionary model of science and technology, moving easily from human prehistory through the current day, toward an ideal future. After airing on Disneyland, they then had a second life in the educational rental market, alongside the Bell Laboratory Science Series. In the films’ narrative arc, the technotopias that Disney envisioned seemed predestined, determined by the necessary arc of human history as it passed into and through Euro-American science.

The translation of these utopic narratives into a technocapitalist playground in the park may seem heavy handed in its branded approach to living, but in the 1950s, when suspicions about corporate motives were muted and brand loyalty a less self-conscious form of belonging, a heavily sponsored future seemed more natural, less fraught than it might today. (Disney and Pixar even gently and vaguely spoofed branded living in the 2008 hit film WALL-E, which featured lives lived within the universe of the Buy and Large corporation.) At the dawn of the Cold War, though, the IBM and Ford’s connections to Nazi Germany, Dow’s role in producing napalm, or General Electric’s vast of array of weapons-related products were not yet widely known by the general public. And although Vance Packard’s The Hidden Persuaders was published in 1957, its insights into brand consciousness and daily life were not quite as detailed, thoughtful, and damning of specific corporations and practices as, say, Sarah Banet-Weiser’s Authentic: the Politics of Ambivalence in Brand Culture (NYU 2012).

Because of this acceptance of corporate conservatorship, the dissonance between the televised versions of Tomorrowland and the rides and attractions on the ground at Disneyland was less pronounced than it was between the electronic and material versions of Disneyland’s other three lands, yet neither was it entirely absent. Each of Disneyland’s four lands plays out a tension that runs through Lefebvre’s model for analyzing social space and its associated practices. The Disneyland television program’s ideal and fantastic spaces of Adventureland, Frontierland, Fantasyland, and Tomorrowland follow the logic of what Lefebvre calls “representations of space,” which he describes as “conceptualized space, the space of scientists, planners, urbanists, technocratic subdividers and social engineers…all of whom identify what is lived and what is perceived with what is conceived.”8 Certainly it was Disney’s goal to attempt that idealized control of space through its “imagineers,” Disney’s trademarked term for its park planners. Yet the distance between the ideal cinematic and televisual spaces of the four lands and their realization on the ground remained irreducible, an example of Lefebvre’s concept of “representational spaces,” which he termed “space as directly lived through its associated images and symbols, and hence the space of ‘inhabitants’ and ‘users’…. This is the dominated—and hence passively experienced—space which the seeks to change and appropriate.”9

Try as it might, Disney could not control relations on the ground, nor reproduce the meanings Disneyland viewers might have produced in consuming Adventureland, Frontierland, Fantasyland, and Tomorrowland on TV. Imagineering was the impossible practice of aligning the imagined narrative of Disneyland/Disneyland as the embodiment of Walt Disney’s weltanschauung with its instantiation in each of its four subsidiary lands, and thence with the lived experience of visitors as they moved through the social space of the park. Its success, then, perhaps has had less to do with the park’s design on the ground than with its visitors’ will to believe, to see the narrative even where it has not been evident.

That will to believe, to imagineer an ideal set of relations regardless of their dissonance with life as lived on the ground, continues to inform the Disney narrative. Its 2015 film Tomorrowland attempts to reconcile the utopianism of the original Disneyland with an increasing sense that a blind faith in technology is actually what has delivered the world to its increasingly catastrophic present and a potentially apocalyptic future. Oddly, though, the film resolves this contradiction by suggesting that cynicism about the future is the actual cause of technologically driven dystopic trends…suggesting perhaps that all the world needs do to set things right is return to a fantastically optimistic narrative such as that of Disneyland…to wish upon a star.

Select Bibliography

Bakhtin, M.M. The Dialogic Imagination. Michael Holmquist, ed. Trans. Caryl Emerson and Michael Holmquist. (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1981).

Bettelheim, Bruno. The Uses of Enchantment: The Meaning and Importance of Fairy Tales (NewYork: Vintage Books, 1971).

Giddens, Anthony. The Constitution of Society (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984).

Harvey, David. Spaces of Capital: Towards a Critical Geography (New York: Routledge, 2001).

Lefebvre, Henri. The Production of Space. Trans. Donald Nicholson-Smith (London: Blackwell, 1974).

Image Credits:

1. Disneyland Map

2. Disneyland

3. Main Street, U.S.A.

4. Frontierland

5. Fantasyland

6. Tomorrowland

7. The Simpsons

8. Tomorrowland

Please feel free to comment.

- Translated by Stephen Heath, 1977. [↩]

- Lefebvre, Henri. The Production of Space. Trans. Donald Nicholson-Smith (London: Blackwell, 1974), 3. [↩]

- Rabinovitz, Lauren. “Urban Wonderlands: the “Cracked Mirror” of Turn-of-the-Century Amusement Parks.” Electric Dreamland: Amusement Parks, Movies, and American Modernity (New York: Columbia University Press, 2012), 25-64. [↩]

- Rydell, Robert. “Forerunners of the Century-of-Progress Expositions.” World of Fairs: The Century-of-Progress Expositions (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993), 15-37. [↩]

- Theatre Magazine Advertiser, n.d. [1902?], Robinson Locke Collection, folder 2461, Special Collections, Performing Arts Library, New York Public Library. [↩]

- See Sammond, Babes in Tomorrowland: Walt Disney and the Making of the American Child, 1930-1960 (Duke University Press, 2005), pp. 195-246. See also Chris, Cynthia. Watching Wildlife (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2006). [↩]

- See Erikson, Erik. Childhood and Society (New York: W.W. Norton, 1950), 248-280. [↩]

- Lefebvre, 38. [↩]

- Lefebvre, 39. [↩]

Pingback: The Disney ReaderNicholas Sammond / University of Toronto – Flow

Pingback: Golden Oak, Fan Engagement, and Disney’s Community Development | Mediapolis