Investing in Girl Play: Kickstarting a New Era of STEM Toys?

Avi Santo / Old Dominion University

In my prveious Flow post I argued that MGA Entertainment’s transmedia product(ion), Project MC2, was marketing STEM as a lifestyle for tween girls. I also argued that MGA’s motivations for entering this market were likely less about wanting to shift the tide in girls pursuing engineering degrees and more about competition from emerging toy companies specifically claiming this demographic of girls, tweens, and parents concerned about the mainstream toy industry’s seemingly archaic adherence to reductionist gender binaries.

This post takes a closer look at a few of these so-called industry outsiders who are leading the charge to change girls’ play culture and guide them toward future STEM fields. More specifically, I analyze the ways these companies have positioned themselves to ‘consumer-investors’ on crowdfunding sites like Kickstarter and Indiegogo. While my objective is not to deter from the likely genuine desires of these companies and their founders to make positive interventions into girls play culture, I do seek to demonstrate how they strategically construct both the scope of their interventions and their own legitimacy as interventionists.

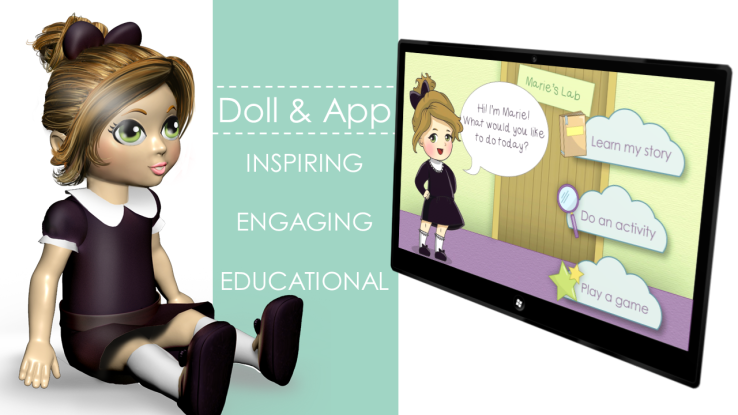

The examples I draw upon are from the Kickstarter campaigns for Goldieblox, Roominate, and i-Besties: Middle School Moguls and the Indiegogo campaign for Miss Possible. The first two originate as construction toys (though Goldieblox has since introduced an action figure line) while the other two brands are dolls accompanied by multimedia extensions that offer varying degrees of interactivity (GoldieBlox and Roominate have also recently ventured into app-enabled enhancements for their physical toys). All four companies launched their crowdfunding campaigns between May 2012 and June 2015 and all four exceeded the dollar amounts they were seeking to raise.

All four companies were launched by women with advanced degrees in STEM or MBAs, which is notable considering the dearth of female executives in the toy industry (LEGO has 22 men and 2 women in leadership roles; Mattel employs 11 men and 1 woman on its Board of Directors). Debbie Sterling (GoldieBlox), Alice Brooks and Bettina Chen (Roominate), Supriya Hobbs and Janna Eaves (Miss Possible), and Gina and Jenae Heitcamp (i-Besties) all looked to establish their credentials as engineers, scientists and business experts, but not as toy industry insiders, in building support for their cause. This positioned them as outsiders bringing new ideas to a stale male-dominated medium, but also as novices and idealists, which potentially undercut investor confidence in their ability to follow through on their initiatives. Unsurprisingly, Sterling was quick to point out that GoldieBlox was supported by the founders of Cranium and Klutz Press, two men with longstanding reputations as toy industry innovators who sold their startups to Hasbro and Scholastic. Likewise, Brooks and Chen noted that their product had been backed by entertainment and media mogul Mark Cuban after having been pitched on an episode of Shark Tank. In general, the founders foreground the relationships they had built with veteran toy manufacturers and distributors as assurance that their outsider status was more rhetorical than infrastructural.

Importantly, all 7 women used their college experiences as de facto origin stories for their products, reciting almost verbatim their shock at how few other girls were in their programs (MGA’s Isaac Larian also offered a ‘where are all the girls?’ epiphany for launching Project MC2 – albeit 35 years after he graduated from college – suggesting that this trope has quickly crossed over into mainstream efforts to sell STEM toy lines). They all then proceeded to make the spurious leap from low female enrollments to the lack of play options for girls, suggesting “you can’t be what you can’t see.” By spurious I don’t mean to suggest that they mischaracterized the state of girls toys, which is strongly entrenched in domestic, social, and appearance-based play scenarios, but rather, that their correlation selectively focuses on play objects rather than play environments. Brooks and Chen explain how their love for engineering stemmed from childhood experiences like Brooks’ father giving her a saw instead of the Barbie she requested and Chen growing up building LEGO creations with her older brothers and giving “no thought to gender differences in toys.” Though these disclosures are intended to justify the need for the products being ‘kickstarted,’ they also inadvertently undermine their effects-based arguments by revealing how parental interventions and gender-neutral household dynamics were ultimately the greater influencers on these women’s career paths. Here the rhetoric of parental intervention is transferred onto investing in the product lines being developed.

Also of significance is the way these campaigns go out of their way to reassure potential contributors that playing with STEM toys will not sap girls of their essential ‘girlyness.’ This message is conveyed on two fronts. First, the seven CEOs establish that they have not lost their femininity despite pursuing science and engineering careers. Sterling twice repeats that she enjoys pink princesses and playing dress-up while also advocating that girls are “so much more than that.” Her campaign video features her sitting criss-cross applesauce on the floor in what is presumably her house rather than behind the desk at her office, which both juvenilizes and domesticates her ambitions. Hobbs and Eaves recount that they thought up Miss Possible in their dorm room while sharing “a pack of gummy worms (yummy!),” a rhetorical maneuver that ‘cutifies’ their business plan.

Second, the products pitched fit comfortably within established tropes of girl play culture. Roominate offers girls the opportunity to build and design their own dollhouse: “Designing the room ties the experience back to common play patterns that we know girls love!” [1] i-Besties seeks to take advantage of girls “already established play patterns” with dolls and doll fashions to ‘edutain’ them about “modern concepts of entrepreneurship and technology.” Hobbs and Eaves brag that the Miss Possible doll with have a “vinyl body and brushable nylon hair (like Barbie).” GoldieBlox reminds parents that an essential difference between boys and girls is that while the former have innate spatial skills the latter have superior verbal ones (read, boys are naturally good at unstructured play while girls take instruction well), which is why GoldieBlox combines building with stories that guide girls through the process. While some of this might be interpreted as a set of backdoor strategies to get girls interested in STEM, it also normalizes the industry’s status quo when it comes to gendered tastes and segregated sensibilities, offering product differentiation within established toy and consumer categories rather than challenging the logics of retail toy shelf slotting.

The embrace by most of these entrepreneurs of the industry standard that kids want toys (or at least packaging) that somehow look like them is perhaps most apparent in their nod toward supporting diversity in their products. Miss Possible declares that “We want every girl to see powerful role models who look like her” accompanied by a promise that their second doll will be of African American aviator Bessie Coleman (the Kickstarter campaign is to prototype their Marie Curie doll), while i-Besties enthuses that the doll line is “as diverse as the girls who love them. Distinct in culture, personality and talents, they come from backgrounds that include blended, bi-racial, military and single-parent households.” Just like Miss Possible, however, their initial prototype doll, McKenna is Caucasian (she is also the self-identified ‘business boss’ of the group whereas the other non-white members have more discernibly exploitable high-end skills like coding and graphic design). In both instances, whiteness remains the default product that must succeed in order to get a complete racially-diverse set. [2] Diversity is also seemingly vinyl skin deep in the sense that there is virtually no address of diverse experiences or reasons why girls of color might either embrace or reject STEM. In this regard, the promise of diversity mimics the industry’s current reduction of race to a color dye rather than a socio-historical condition that influences and impacts everything from play possibilities to career opportunities.

Finally, it is important to place efforts to inspire a love of STEM through play within the context of entrepreneurship. While it is a common refrain within these campaigns to suggest that more women becoming involved in STEM will make the world a ‘better place,’ there is a decidedly careerist bend to this notion. i-Besties bluntly states its goal to inspire girls to become CEOs, but all of the projects loosely connect improving the world with the success stories of their companies’ founders. Simply put, through the logic of crowdfunding, an investment in Roominate is both an investment in girls’ futures and in the present ambitions of the women who founded the company. While there is absolutely nothing wrong with encouraging more women to become scientists, engineers, and business-owners, there is some concern that tying this accomplishment to entrepreneurship’s investor model places the responsibility on consumers rather than public institutions. Entrepreneurship’s focus on market competition and executing sustainable business plans contributes to the conversion of young girls into customers rather than seeing them as a community with shared interests in STEM. Notably, none of the companies I’ve discussed share any of the proprietary science or engineering behind the products they are selling, nor do they acknowledge their own complicity in taking STEM jobs away from both girls and boys through their contracting of more cost-effective overseas manufacturers and product testers (granted these aren’t the sexy STEM jobs imagined as making the world a better place).

The arrival of STEM toys brings with it a lot of excitement for play’s potential to change the demographic makeup of the next generation of scientists and engineers. How that potential is refracted through the toy industry’s entrenched product and consumer categorization practices remains to be determined. Despite the celebration of crowdfunding’s ability to circumvent the established industrial etiquette by appealing directly to consumers as investors, the girl inventor promoted by all these initiatives still seems constrained by the need to embrace a market-friendly invention of girlhood.

Image Credits:

1. Roominate header

2. Miss Possible

3. i-Besties

4. GoldieBlox

5. Debbie Sterling’s kickstarter pitch video (author’s screen grab)

6. Dollhouse interior decorating

7. Miss Possible diversity

8. Roominate in Wal-Mart

Please feel free to comment.

- To Roominate’s credit, their second crowdfunding campaign openly celebrates the diverse creations girls have made with their product, which include cars, space ships, a replica of the Golden Gate Bridge and other non-domestic designs. [↩]

- Roominate again proves the exception with all of its packaging featuring non-white girls playing with the toy and its initial mini-figures based on childhood versions of the company’s founders, who are both Asian-American. [↩]

Pingback: RETROMANIA

Pingback: “Its Not Just a Doll; It’s a Social Movement”: Investing in Black Toys Then and Now Avi Santo / Old Dominion University – Flow