Wicked Games, Part I: Twenty-sided Demons

Matthew Payne / University of Alabama

Peter Alilunas / University of Oregon

Conventional wisdom tells us that there is “no such thing as bad publicity.” Video game firms have long embraced this questionable truism in a range of marketing campaigns aimed at teens and adults. Game publishers’ ads appearing on billboards, in magazines, TV spots, websites, and social media regularly trade in a range of socially taboo subject matter: race, [1] drugs, [2] death, [3] sex, [4 ] violence, [5 ] sex plus violence, [6] and occasionally just inexplicable undead weirdness. [7 ] Generally speaking, the goal is to raise gamers’ eyebrows, not their ire.

Of course, flirting with the boundaries of what is socially acceptable in the service of moving product routinely results in mishaps that attract the wrong kind of attention and threaten to sabotage sales. To wit, the director of Activision’s Call of Duty: Black Ops III (2015) apologized after the company used Twitter to circulate a fake news account of a terrorist attack in Singapore. [8 ] Evidently, the 18 tweets about the “attack” were intended to promote the game’s near-future narrative action.

Backlash to tone-deaf marketing efforts are not restricted to mediated channels, however. At the 2011 Game Developers Conference in San Francisco, hundreds of red balloons were released as a publicity stunt in support of THQ’s upcoming first-person shooter Homefront (2011). [9 ] Condemnation quickly mounted though as many balloons ended up in the city’s bay, raising concerns about the event’s unintended environmental effects on local marine life. The preceding marketing snafus are fairly limited in scope and in duration. But this isn’t always the case. Indeed, there are a handful of controversial moments in gaming history that are so seismic and consequential that they not only rose to the level of national dialogue, they permanently changed the popular discourse around games.

In our three columns, we will examine flashpoints in gaming history with the goal of exploring how popular controversies reveal deeply held beliefs regarding the intersection of technology, play, pleasure, and social taboos. What happens, for instance, when media and entertainment companies lose control of how their games are perceived? What about when the problem is no longer about a single game or its marketing, but is emblematic of an entire industry and its playthings? Worse still, what about when games are thought to jeopardize public safety; or, to quote Helen Lovejoy of The Simpsons fame, “Won’t somebody please think of the children?”

We seek, first, to examine various engines of gameplay and their production of pleasurable play, and then ask why and how those experiences became lightening rods of controversy that seemingly demanded regulation. Our goal is to showcase how cultural and commercial stakeholders create and regulate gaming pleasures for dissimilar ends. And because we are interested in understanding gameplay’s cultural politics across different times and spaces—from fantasy play in the 1970s, to industry battles in congressional hearings in the 1990s, to hidden code in the 2000s—we are casting widely to appreciate how gameplay’s magic circles get coded as deviant, thereby justifying the intervention of outsiders (e.g., critics, religious leaders, policy makers, politicians, etc.) seeking to re-establish “acceptable” boundaries.

Case Study #1: Dungeons & Dragons

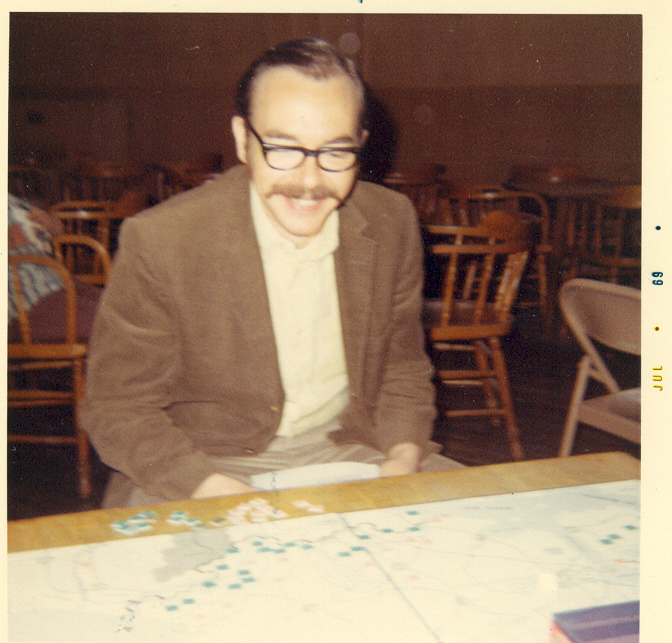

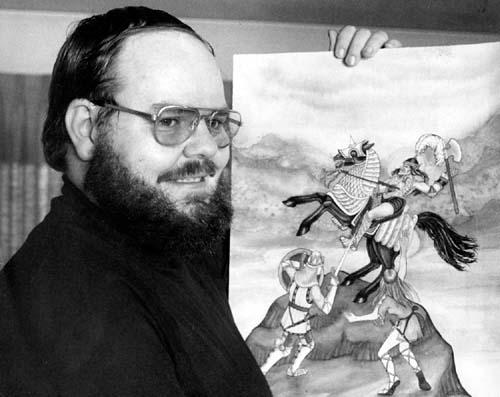

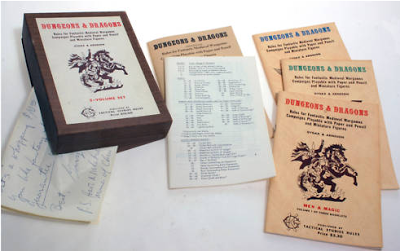

Such discourses were rendered visible in our first case study: Dungeons & Dragons (D&D). This tabletop game, created by Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson in the early 1970s, combined the tactical decision-making of war-focused boardgames with the high fantasy narratives and settings popularized by authors like J.R.R. Tolkien (The Lord of the Rings) and C.S. Lewis (The Chronicles of Narnia). The result was an evolving rule set engendering an immersive, open-ended role-playing experience for two or more players. D&D was first published in 1974 by Tactical Studies Rules, Inc. (TSR), a company formed by Gygax and investor Don Kaye.

The initial audience was part of a larger community of science fiction and fantasy enthusiasts. Typically, they were white, middle-class, and middle-aged men interested in simulating battlefield tactics of historical conflicts such as the Napoleonic Wars, the American Civil War, and World War II. Although tactical wargaming had been around since the turn of the century, tremendous growth began in the late 1950s. [10 ] But D&D was something else altogether, quickly turning from an underground activity for hobbyists into a cultural phenomenon. Gygax estimated in mid-1979 that 250,000 Americans were playing the game, and around 6,000 sets selling each month. [11 ]

Once the sales boom boosted the game to cultural phenomenon, D&D quickly became ensnared in larger cultural debates about the appropriate boundaries of play and shared imagination. The moral panics and hand-wringing over vulnerable youth that were gripped by D&D both looked backward, reprising concerns around comic book readership, and previewed what was to come later with video games (which we will examine in future columns).

If D&D’s player communities reveled in sharing detailed, imagined realms—narrative play made possible by having a dungeon master (the game’s referee and primary storyteller) adjudicate complex rules with dice throws—it was precisely this shared headspace that fueled the initial panic. Outsiders wondered: What effects might sustained periods of shared fantasy have on users? D&D’s signature accouterment did little to dispel myths of sorcery and the occult: cloth maps, multi-sided dice, character sheets with strange characters and foreign runes. Of course, these were minor factors compared to the collaborative gameplay proper: improvised, fantastic, and not easily regulated by outside interests.

There was also considerable confusion about what D&D was exactly; after all, the game was not played in the conventional, competitive sense. Moreover, D&D was open-ended, it lacked a “winner” and “loser,” and its gameplay was emergent, created by its users as it happened. D&D featured meticulously detailed worlds starring monsters and magic, all of which was predicated on complex rule sets and player ingenuity. One early newspaper description described it as “frightfully complex.” [12 ] The complex rules, immersive gameplay, and devotion of its community combined to make D&D an object of mass suspicion.

The primary fear surrounding D&D was that its players, typically described as children and adolescents, would not be able to distinguish fantasy from reality. If such fears simmered under the surface during the initial rise of the game’s notoriety, that all changed in August 1979 at Michigan State University. It was there that James Dallas Egbert, a 16-year-old sophomore computer science prodigy went missing. Within weeks, Egbert’s story — and D&D — became national news. Replete with curious clues, a suspicious suicide note, and anonymous tips, the mystery of the missing student was made even more bizarre by Egbert’s fascination with D&D. The game would come to occupy the nation’s attention because the Egbert family’s hired investigator, William Dear, possessed a deft understanding of how to generate publicity and manage the media’s attention.

Dear’s sensationalism strategy triggered an avalanche of suspicion and tension around D&D that became all but inseparable from its cultural meaning and legacy. Dear fed the national press exactly what an anxious public was ready and waiting to hear. The initial reports captured the breathless fear that had embroiled D&D: Egbert may have become “the victim of an elaborate intellectual fantasy game that may have become all too real.” [13 ] Familiar elements appear here that define panics around games: rules and gameplay mechanics that are dangerously complicated; a fear of the game being too “smart,” and thus disconnected from more grounded, physical play; and, most importantly, escaping too far into fantasy, making it all but impossible to return to the “real” world.

These multilayered fears were epitomized by the fascination with a set of steam tunnels under the MSU campus, where Egbert was possibly dead or hiding. A D&D group on campus was rumored to have played in the tunnels, and now the public feared Egbert was trapped there in some bizarre conflation of game/reality. They were the perfect embodiment of the “too real” fears around a game that literally had “dungeons” in its title. Egbert’s young age and vulnerable status—he was already “trapped,” as it were, in an intellectual space typically occupied by older people with more experience—made him the perfect image on which to project such concerns.

In the end, Egbert was not in the steam tunnels, and though he played D&D, his disappearance had nothing to do with the game. In mid-September, after discovering the national media attention, Egbert contacted his family (and Dear) and put the speculation to an end. He had taken a bus to New Orleans and unsuccessfully attempted suicide. He suffered from severe depression; a year later, he killed himself. [14 ] The Egberts publicly told their son’s story, criticized Dear as a “flamboyant” opportunist just as interested in selling the movie rights as finding their son. [15 ] They tried to downplay the D&D connections, but the damage was done: by that point, the game was no longer just a confusing intellectual object, it was now a target of suspicion that needed to be reined in before it could do more damage.

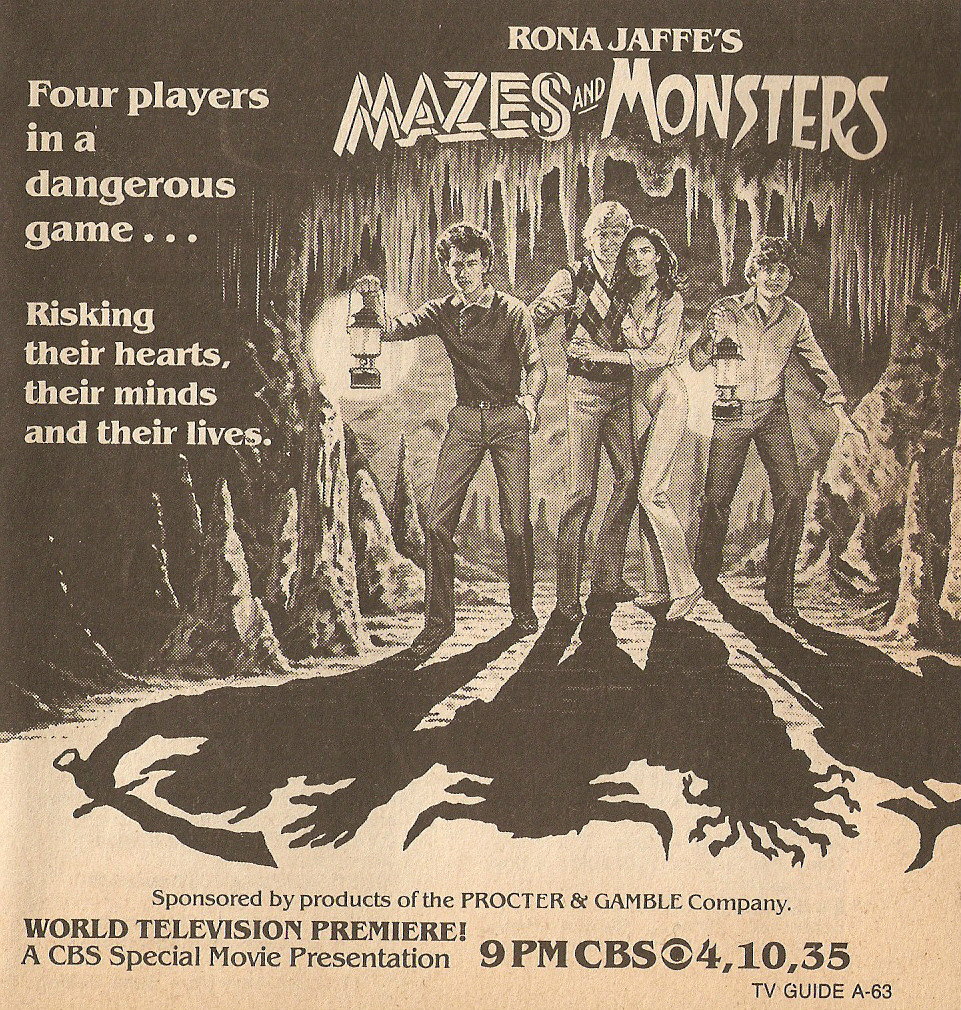

Following the Egbert story, the discourse shifted to include the possibility that D&D wasn’t just a game. This framing is evident in a New York Times report in October 1979 on the game’s popularity: “What is this game, which its players call D and D? Is it a harmless battle of wits and craftsmanship originated by J.R.R. Tolkein, the science-fiction and fantasy writer? Or is it a bizarre exercise involving the occult?” [16 ] The 1982 made-for-television film Mazes and Monsters (dir. Steven Hilliard Stern), starring a young Tom Hanks, was even more sensationalistic—telling the story of a college student obsessed with blurring fantasy and reality in a D&D-like game, effectively delivering to the public the story they didn’t get the first time. [17 ]

In the 1980s, D&D’s reputation as a site of dangerous play intensified even as it grew in popularity. This twin effect is not coincidental: the taboo object became increasingly popular because of the moral panic. Colleges began banning the game, communities held heated meetings, and school boards were forced to decide whether or not D&D could be played by after-school clubs. “I can feel the devil right here in [this room],” said one parent in Utah during a meeting, demonstrating the growing fear that D&D played literally with satanic power. [18 ]

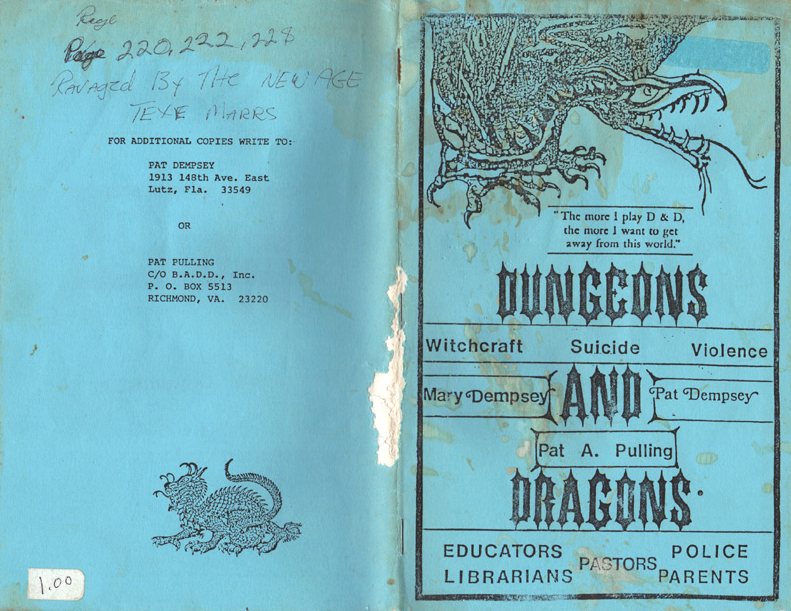

By 1983, the backlash coalesced into a clear set of discourses pitting normal play against the dangerous fantasy/reality world of D&D that led to horrifying consequences. Patricia Pulling, whose 16-year-old son committed suicide in 1982, not only blamed D&D, she sued TSR, accusing the company of negligence. She claimed that, hours before his suicide, another player had placed a curse on her son during a game. Even though the lawsuit went nowhere, Pulling did not give up. [19 ] She formed “Bothered About D&D and Other Harmful Influences on Children” (B.A.D.D.), creating newsletters, pamphlets, giving interviews, working in an advisory position to community leaders, acting as an expert in court, and generally establishing herself as the voice of concerned parents everywhere. Her B.A.D.D. introductory letter illustrated how D&D was merely one cog in a much larger cultural wheel:

We are concerned with violent forms of entertainment such as: violent-occult related rock music, role-playing games that utilize occult mythology and the worship of occult gods in role playing situations like Dungeons & Dragons (R), teen satanism involving murder and suicide, and pornography as it is affecting adolescent behavior and reshaping attitudes and values in a negative manner. [20]

Like Dear, Pulling turned to sensationalist tactics—citing alarming, but exaggerated and decontextualized, statistics to make her case. That case was always rooted in D&D’s vague capacity to illuminate the edges of the boundary between reality and fantasy for a vulnerable population. “With 6,500 teens committing suicide and over 50,000 attempts every year, we cannot afford to overlook a ‘game’ that teaches witchcraft, Satan worship and a cult-like religion not to mention specific suicide phrases,” wrote Pulling, using the tone that captured the vivid and frightened imagination, ironically, of many seeking just such rhetoric. [21 ]

Throughout the 1980s, D&D was also blamed in court for all manner of violent incidents involving children and youth—especially when there was any connection, however tenuous, to the occult. In November 1984, for example, after two teenage brothers committed suicide together in Colorado, the national media reported it as a “suicide fantasy involving Dungeons and Dragons.” [22 ] When another teenager strangled two school friends that same month outside of Toronto, a psychiatrist testified that the boy had been reading a D&D book the morning of the murders. [23 ] Similar examples from this period can be found across North America. D&D became a dangerous menace that required legal disciplining and boundaries.

TSR’s response throughout all of this was remarkably restrained and quiet, given the charges that were being leveled. Occasionally, Gygax would comment—such as when he called some of Pulling’s accusations “witch hunting balderdash”—but mostly the company remained focused on growing its customer base and profit margins. [24] By the time of Gygax’s death in 2008, D&D had sold an estimated $1 billion worth of products, and more than 20 million people were estimated to have played the game since its creation. TSR was acquired by Wizards of the Coast in 1997, which was later acquired by toy giant Hasbro. D&D lives on in online and tabletop versions, where it continues to inspire creativity and imagination as well as provoke the occasional fear, though nowhere near the panic of the 1980s. [25 ]

In Flow 22.04, we will leap forward to the early-to-mid 1990s to examine the video game industry’s (semi-)coordinated attempts at self-regulation following outcries about violent content. But before we transition from D&D to the ESRB (Entertainment Software Ratings Board), it bears asking: if culture’s compunction to regulate the magic circle of play is nothing new, then what might we learn from placing historical case studies into dialogue? We have two provisional responses. First, these cyclical flashpoints offer detailed insights into a historical moment’s preoccupations with taboo subjects. In the case of the “missing” Egbert, D&D became a convenient scapegoat for moralists seeking a ready-made crusade. The evocative fantasy art covering the books and magazines, the colorful, multi-sided dice, and the long, ritualistic play sessions offered more than enough evidence that D&D was an engine for sinning. Even the passage of several decades and the failure to link D&D to its reputed social ills has done little to erase those infamous, formative associations. The dark side of D&D’s cultural legacy brings us to a second potential insight; a point that has less to do with the specific details of the games than the experiential play that breathes life into them. Play is many things; it is frolicsome, precarious, elusive, and ephemeral. In short: play’s liminality and hidden imaginary make it threatening precisely because control is never a given. The gaming controversies we chronicle are, in effect, battles about what may or may not be imagined.

Image Credits:

1. A Dungeons and Dragons Campaign

2. A meme of Helen Lovejoy’s panicked refrain

3. Gary Gygax

4. Dave Arneson

5. Original Game set of Dungeons and Dragons

6. Private investigator William Dear

7. 1982 advertisement for Mazes and Monsters in TV Guide

8. Patricia Pulling’s anti-D&D pamphlet (author’s screen grab)

Please feel free to comment.

- Ryan Block, “Sony Under Fire for ‘Racist’ Advertising,” Engadget, July 6, 2006, http://www.engadget.com/2006/07/06/sony-under-fire-for-racist-advertising. [↩]

- Jeff Rouner, “Video Game Marketing Campaigns That Will Make You Go WTF?, Houston Press, August, 25, 2015, http://www.houstonpress.com/arts/5-controversial-video-game-marketing-campaigns-7696352. [↩]

- Mark Oliver, “Game Publicity Plan Raises Grave Concerns,” The Guardian, March 15, 2002, http://www.theguardian.com/technology/2002/mar/15/games.advertising. [↩]

- “Dreamcast: “SEAMAN” Print Ad by FCB Chicago,” Creative Advertising & Commercial Archive, September, 2001, http://www.coloribus.com/adsarchive/prints/dreamcast-seaman-3509905/. [↩]

- Shaun Munro, “10 Outrageous Video Game Adverts That Caused Major Controversy,” What Culture, July 23, 2013, http://whatculture.com/gaming/10-outrageous-video-game-adverts-that-caused-major-controversy.php/9. [↩]

- Jason Schreier, “This Game’s Special Edition Comes With A Statue of a Bikini-Clad, Severed Female Torso,” Kotaku, January 15, 2013, http://kotaku.com/5976075/this-games-special-edition-comes-with-a-statue-of-a-bikini-clad-severed-female-torso. [↩]

- “Weird Resident Evil 4 TV Commercial,” YouTube, uploaded May 19, 2006, https://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_embedded&v=HEVCW8oMN5M. [↩]

- Kyle Orland, “Call of Duty Developer Apologizes for Fake Terrorist “News” Twitter Promo,” ArsTechnica, October 13, 2015, http://arstechnica.com/gaming/2015/10/call-of-duty-dev-apologizes-for-fake-terrorist-news-twitter-promo/. [↩]

- Owen Good, “THQ Homefront Balloons Don’t Fly in San Francisco,” Kotaku, March 2, 2011, http://kotaku.com/5774934/gamestops-balloons-dont-fly-in-san-francisco. [↩]

- William Gildea, “War Games Fascinate Thousands,” Los Angeles Times, November 28, 1975, H1; Mary Rourke, “Fantastic Voyages,” Newsweek, July 11, 1977, 49. [↩]

- Gildea, H1; Rourke, 49. [↩]

- Beth Ann Krier, “Fantasy Life in a Game Without End,” Los Angeles Times, July 11, 1979, H1. [↩]

- “Fantasy Game May Have Claimed Missing Genius,” Los Angeles Times, September 7, 1979, A2. [↩]

- William Robbins, “A Brilliant Student’s Troubled Life and Early Death,” New York Times, August 25, 1980, A20. [↩]

- In 1984, Dear published The Dungeon Master, which recounted his experiences searching for Egbert in his trademark sensationalist tone. [↩]

- Linda Lynwander, “’D and D’ Plus Sci-Fi,” New York Times, October 7, 1979, NJ10. [↩]

- Mazes and Monsters was based on Rona Jaffe’s novel of the same name from 1981, which was a work of fiction loosely based, in part, on the media coverage surrounding the Egbert case. [↩]

- Molly Ivins, “Utah Parents Exorcise ‘Devilish’ Game,” New York Times, May 3, 1980, 8. [↩]

- Michael Isikoff, “Parents Sue School Principal; Game Cited in Youth’s Suicide,” Washington Post, August 13, 1983, A1. [↩]

- Mary Dempsey, Pat Dempsey, and Pat Pulling, “Introduction,” Dungeons and Dragons, N.D., from the authors’ collection. [↩]

- Dempsey, Dempsey, and Pulling, “Introduction.” [↩]

- “Young Brothers Found Dead,” Washington Post, November 4, 1984, A6. [↩]

- Thomas Claridge, “Orangeville Slaying Victims were Stand-Ins, Trial Told,” The Globe and Mail, February 27, 1985, NP. [↩]

- GAM, “Where the Dragons Are,” The Globe and Mail, March 25, 1985, NP. [↩]

- Seth Schesel, “Gary Gygax, 69, Game Pioneer, Dies,” New York Times, March 5, 2008, C11. [↩]

Pingback: Wicked Games, Part 3: Caution — Contents May Be Hot… and Hidden Matthew Payne / University of AlabamaPeter Alilunas / University of Oregon – Flow