Girl as Sign: Epistemology of the Shōjo

Coco Zhou / McGill University

The 1995 anime Neon Genesis Evangelion (hereafter NGE) is probably the most heavily marketed and referenced production in the entire Japanese animation industry. The show documents the struggles of Ikari Shinji, who, despite being chosen to battle aliens, is a crybaby who constantly depends on his female colleagues to rescue him. This portrayal of masculinity is subversive in the context of the genre with which NGE is typically associated: shōnen (“young/adolescent boy”), a type of anime and manga (comic books) centered around male heroism.

Given NGE‘s cultural impact, Shinji’s story must have struck a chord with its intended audience: young men who are under immense pressure to achieve culturally-defined success. But there is another way in which NGE portrays this gendered anxiety. It is channeled through the character of Ayanami Rei, Shinji’s colleague. Despite not being the protagonist, Rei has become a character archetype in Japanese media in the wake of NGE‘s success, with many later works featuring female characters with her physical and emotional characteristics. If Shinji symbolizes a failure to perform idealized masculinity, or the anxiety about this failure, what does Rei’s cultural influence represent? There must be a name for that which codifies Rei – the projection of male anxiety through female subjectivity.

The name is shōjo. Literally translated as “young/adolescent girl,” shōjo transcends genre and occupies a distinct space in Japanese visual culture. Characterized as “selfish, irresponsible, weak, and infantile,” the shōjo image has become pervasive to the point of defining the Japanese national character in the postmodern era, perhaps not coincidentally conflating with the colonial construction of Oriental passivity. But shōjo culture also functions in specific ways in Japanese contemporary society, enabling not only female identification but also, more significantly, male identification.

Originating in late nineteenth-century Japan, the modern concept of shōjo emerged in a period of rapid economic change as single-sex girls’ schools were established to fulfill a rising demand for labour. Books and magazines designated “for girls” became popular and helped to define an identity of shōjo during Japan’s modernization. [1 ] By the late twentieth-century, the concept of shōjo has been rearticulated as both a phenomenon of Japanese consumer culture and a model of Japan, which to some critics meant a state of passivity, commodification, and narcissism. Others have defined 1980s shōjo culture more ambiguously; their attitudes toward the shōjo image appear ambivalent, and they also remark on the ambiguity of that image: it is whimsical, elastic, and in a state of “floating.” [2 ]

The overall picture of shōjo-ness that thus emerges from these views is of a slightly troubled, dreamy, yet somehow seductive vulnerability, occupying a space of sexual inactivity and potential between childhood and adulthood. Because this tension is essentially what constitutes the shōjo subjectivity, scholars have argued that the shōjo is its own gender, “neither adult woman nor girl child, neither man nor woman.” [3 ] The non(re)productive space it represents could be seen as a potential site of resistance to the nuclear family as a function of industrial capitalism. The discourse of the shōjo, then, appears to be as rich and contradictory as the sign itself. The shōjo is passive, but also transformative; uncertain, but potentially liberatory. As a main form of girls’ entertainment, shōjo anime and manga have always been more than a reflection of societal concerns about young women’s sexualities. In marketing shōjo-ness to girls, producers of such entertainment encourage girls to consume images of themselves as commodities, identifying them as both consumers and the consumed. [4 ] In other words, shōjo media produces shōjo culture and young women’s desires rather than simply reflecting them. However, attempts to achieve shōjo-ness could also be argued to represent a desire to fulfill a constant lack—unreachable beauty, freedom from adult sexuality and family duty—which drives the consumption of shōjo-related fashion products, such as Hello Kitty goodies. [5 ] Consuming these products is the easiest way for the female subject to embody shōjo and its non-reproductive, static yet promising qualities.

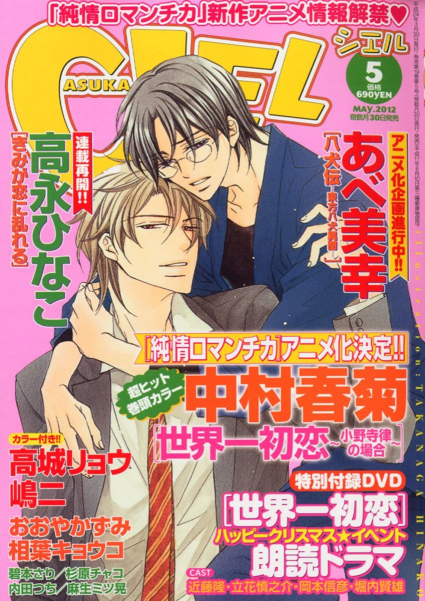

An important and popular stream of shōjo entertainment since the 1970s is the yaoi genre, which exclusively features male homosexual romance. This subgenre of anime and em>manga is predominantly produced by and circulated among women. Although the subjects of these comics are obviously not girls, it is possible to consider them as having shōjo qualities: many of the men are portrayed as beautiful and androgynous, and most importantly, they are young and non-reproductive. [6 ] Another aspect of shōjo-ness in yaoi is the communities of women that revolve around it and share these fantasies amongst each other. The creating and sharing of yaoi, more specifically, serves to enhance the shōjo community by staging a particular way for the shōjo to address one another and identify each other as shōjo, thus highlighting their shōjo characteristics and reaffirming their shōjo identities. [7 ]

While a complex examination of yaoi is outside the scope of this discussion, I want to emphasize a few aspects about the phenomenon. One reason that women writers and artists may

have turned to the depiction of male homosexual relationships is the limitations around writing stories about sexually-active (and reproductive) women, such as pregnancy, which symbolizes a point in one’s life when one stops being shōjo. [8 ] Focusing on young, non-reproductive men is a way to explore romantic and sexual relationships without having to engage with the realities of womanhood in Japan. In this sense, yaoi’s presence reflects the anxieties women have about their social situation. But another reason for its popularity may be its success in enabling women to project their own femininity onto the male characters. In the process of this projection, women not only come to identify with the characters but are also able to identify themselves. In other words, their shōjo status is validated through both objectifying the male characters and “entering” the body of the objectified.

If yaoi is a space for women to fantasize about the possibilities of being the Other (to their own “Other,” so to speak), does the same space exist for men? If shōjo is a screen for the projection of male anxieties about female adolescent sexuality, what are the mechanisms that allow men to take unto themselves the image of the shōjo and identify with it/her? A further examination is needed of the ways in which the cultural production of shōjo enables male identification. [9 ] For now, we have established that shōjo is a phenomenon that has material implications on the ways in which subjects navigate the structures of patriarchy.

Image Credits:

1. Ayanami Rei from Neon Genesis Evangelion

2. Pop star embodying shōjo fashion

3. Cover of Shōjo Beat magazine

4. Cover of a yaoi magazine

Please feel free to comment.

- Treat, John Whittier. “Yoshimoto Banana Writes Home: Shōjo Culture and the Nostalgic Subject.” Society of Japanese Studies 19, no. 2 (1993). [↩]

- Orbaugh, Sharalyn. “Busty Battlin’ Babes: The Evolution of the Shōjo in 1990s Visual Culture.” Gender and Power in the Japanese Visual Field. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2003. 201-27. [↩]

- Quoted in Orbaugh, 204. [↩]

- Prough, Jennifer S. “Material Gals: Girls’ Sexuality, Girls’ Culture, and Shōjo Manga.” Straight from the Heart: Gender, Intimacy, and the Cultural Production of Shōjo Manga. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2011. 110-34. [↩]

- Shen, Lien Fan. “The Dark, Twisted Magical Girls: Shōjo Heroines in Puella Magi Madoka Magica.” Heroines of Film and Television: Portrayals in Popular Culture Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 2014. 177-88. [↩]

- Nagaike, Kazumi. Fantasies of Cross-Dressing: Japanese Women Write Male-Male Erotica. Leiden, Neterlands: Brill Academic Publishing, 2012. [↩]

- Nagaike, 94. [↩]

- Orbaugh, 212. [↩]

- I’m aware that I have been talking predominantly in the gender binary. My intention is not to erase the experiences of those who see themselves in characters that aren’t necessarily of their own gender (assigned or otherwise). As it will hopefully become clear in my subsequent columns, I’m merely trying to demonstrate that this process of identification operates in a specific way in the context of shōjo media, as it is circumscribed within patriarchal hegemony. [↩]

Thank you so much for this piece! The idea of shōjo being more than a genre of anime and manga and instead more of a national “culture” is fascinating. I am actually writing a piece for a class on the hybrid genres in Satoshi Kon’s “Perfect Blue,” and the more I think about it–especially after reading your piece–the more I believe the shōjo “culture” serves as a foundation on which to examine genres. Have you seen “Perfect Blue?” If so, what are your thoughts on it, especially in regards to representations of shōjo “culture?”

Hi Dylan, Satoshi Kon happens to be one of my favourite directors, and “Perfect Blue” is a really interesting text to study. A lot of things happen in the film, but I think notions of identity are at the core of the story. I read the character of Mima as a representation: she is the embodiment of shōjo to those around her. We see men and women engage with her in different ways; whereas her manic fan tries to violently consume her, her female manager wants to become her. I think this dynamic speaks a lot to the ways in which the shōjo image frames and is received by viewers of different genders in the specific cultural context of Japan. As with all representations, shōjo also signifies a lack–the men and women who desperately want to consume/become Mima may never do so wholly and completely. A psychoanalytic inquiry into this text would be really fascinating.

Pingback: A Girl Divided: the Fragmented Shōjo in Perfect Blue Dylan Levy / University of Texas at Austin – Flow

Pingback: Dissertation: Reviewing sources of information (1) – Shaih-Marie Sedeno