Seasonal TV, Hammer Horror’s Cult History, and TCM’s Tele-Binging Convergence Model

Garret Castleberry / Oklahoma City University

Each October, cable channel Turner Classic Movies (TCM) rotates a slew of vintage horror movies based upon available archives under contract. In 2010, TCM showcased former British film production company Hammer studios, complete with their eclectic horror movies of the 1950s, 60s, and 70s. Hammer horror films carry a unique look and subsequent aesthetic ambiance reflective of the studio’s pension for rich stagecraft planning and lush Victorian costuming despite razor thin budgets. As a benchmark industry innovation, Hammer horror boasts the first color horror films released for moviegoing audiences. In typical TCM fashion, pre-recorded bumpers prime viewers for these B-movie marathons, supplying industry tidbits and other arcane trivia. Since 2010, TCM continues to air Hammer horror films each October, albeit more scattered and with less showmanship. The packaging of related content, particularly the intertextual mise-en-scène representative of Hammer’s industrious studio history, functions as a visual spectacle for cinephiles familiar and foreign to their film canon.

Hammer’s recurring tropes possess textual and intertextual qualities, making these cult classics insightful to watch in conversation with one another. Hammer often redressed the same sets over and over, tweaking lighting design, costuming, and props to re-disguise scenes. The aesthetic effect conjoins visual distinction with resonant repetition. One unintentional impact is that many iconic scenes and settings conjure otherwise unrelated Hammer horror films. In a sense, the visual admixture thus haunts subsequent films in their gothic horror canon. In this essay, I consider the industry methods Hammer and TCM communicate in through their cyclical formulas of re-presentation.

Prior to their success within the horror genre, Hammer Films functioned as a low-budget British production company relatively unheard of to American audiences. In the 1950s Hammer Studios acquired the rights to Universal Studios’ once-lucrative marquee horror film monsters, including Dracula, Frankenstein, the mummy, and the wolf man. Decades before, Universal Studios broke box office records and Hollywood taboos alike with cinematic introductions to these horror creations. Universal’s collective cinematic translation set supernatural monsters apart from their literary counterparts in large part due to the sheer [social] spectacle cinema provides. One contractual catch with the negotiated release of character rights stipulated newly produced versions bare no visual resemblance to the iconic look Universal once profited from. In short, visuality played a central role in processes of acquisition and translation, requiring an obscure production company inexperienced in horror cinema to reinvent a product long since saturated by conventional audiences.

By the late 1940s, American audiences grew tired of traditional monsters characterized in horror. Such a shift in audience taste can be assessed on a historical and theoretical trajectory. First, in part due to the real-world horrors experienced during and coming out of World War II, audiences rejected such fantastical creations as Dracula and Frankenstein in favor of more “resonant violations” with the onset of the Cold War. [1] These resonant violations coincided with ideological shifts in the collective American consciousness, and a general movement toward conservative perspectives in life and in art. Noting generational shifts is important to understanding a second theoretical claim, that the Universal monsters had reached a impasse in their genre lifecycle, to the point where Frankenstein and others were featured in crossovers like vaudevillian comedies alongside Abbott and Costello (think of this as generic precursors to the Hanna-Barbara Scooby Doo’s to come decades later). In effect, the affect was broken, and the medium’s genre cycle required an innovative reboot to remind audiences of the semiotic power these artifacts wield.

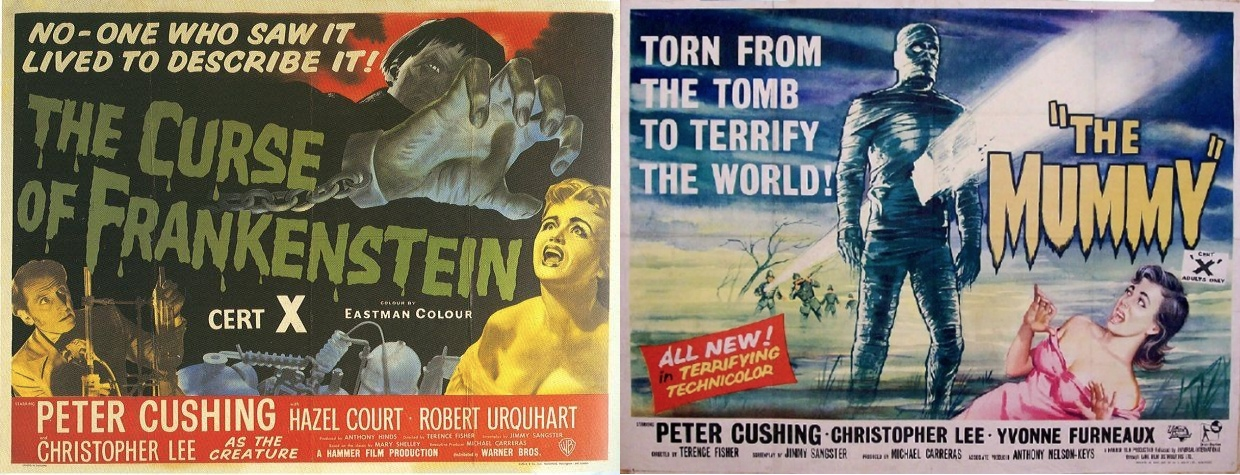

Starting in the mid-late 1950s through the early 1970s, Hammer Studios rewrote the script on the horror genre, challenging boundaries of moral decency through the subversive (and successful!) use of gothic horror as an ethical compromise between conservative mythologies and progressive textualities. Hammer horror constituted the first mainstream studio effort to translate horror pictures into glorious Technicolor, exciting audiences and censors with the canonization of onscreen gore. The results were monumental, leading Hammer to years of successful franchising and sequelizing in ways that ought ring familiar with contemporary Cineplex audiences. Film series starting with The Curse of Frankenstein (1957), The Horror of Dracula (1958), and The Mummy (1959) became concomitantly associated with the career-defining works of Peter Cushing and Christopher Lee (no coincidence, George Lucas used both as a meta-fan homage within his Star Wars saga). Like the redressed sets, costumes, and props, Hammer exhausted recombinations of Hammer’s stock actors. Yet as time progresses, so do audience tastes, preferences produced by and reflected within popular culture. Indeed Hollywood film studios continue, often in vain, to exploit the pantheon of public domain characters for mass marketed simulacral commodification. But where does the line draw between film history fandom and industry commoditization?

Despite the epic run of sensation horror films, Hammer met a tragic end by end of the 1970s. A short-lived horror anthology series did not resuscitate the studio. Ultimately Hammer closed its doors just as slasher franchises took hold of teens in the 1980s. Hammer largely remained dormant, a relic in cinema history, until its resurrection by TCM. As previously noted, TCM offered red-carpet treatment (and cult-like devotion) in 2010 with a weekly spotlight complete with the cabler’s iconic brand of paratextual discourse. In subsequent years since, Robert Osborne, Ben Mankiewicz, and even comedian Bill Hader hosted some of TCM’s signature vignette bumpers, transforming Hammer horror marathons from cinematic aesthetic to something resembling binge-watching in its televisual form.

Vignettes exude a performative value in their own right that adds an informational aesthetic value to the screen text, particularly former B-movies traditionally relegated to follow-up feature status at drive-ins (another ghostly paratextual communal experience altogether). Uniquely, this informational aesthetic value functions as paratextual discourse through further intertextual referencing. The combined efforts situate a context for viewers familiar and foreign to Hammer. For repeat viewers, the ritualistic repetition of insider information blankets the text in a refurbished reassurance that becomes appointment viewing, marked by TCM’s bookend intros and outros and pseudo-celebrity hosts.

TCM’s self-referentiality as an “archive” legitimates their status (in audiences minds) as a premiere cable channel. At the same time, the programming function promotes access to hard to find (e.g. “sacred”) cultural texts while also practicing exclusivity by withholding particular features until certain seasons or rotational themes circulate again. Such give-and-take tension performs a kind of televisual burlesque show akin to Hammer’s gothic horror tropes; for example, the Victorian tension between sexual repression and expression, visualized onscreen through claustrophobic multi-layered full body suits and dresses juxtaposed against strategic cleavage and recurring nightgown tiptoeing throughout drafty castles. Thus, the product becomes transformative, as the texts reinforce the channel while the channel’s programmers purport a unique access portal for viewers.

TCM’s October strategy, along with other campaigns like their routine Summer under the Stars “festival,” suggests a seasonal approach to programming not unlike traditional networks with contemporary scripted shows. This affords TCM the luxury of blurring lines between viewing and screening, including infrequent and thus exclusive habits like advertising TCM Presents theatrical specials, including a two-date rerelease of Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho in conjunction with Fathom Events in fall 2015. Bringing the public/private, inclusive/exclusive cycle full-circle, Psycho’s theatrical mini-release features vignette bumpers from TCM’s second-most recognizable host, Ben Mankiewicz. This synergistic strategy communicates telling insight into the state of the film and cable television industries and the effect Internet and streaming services have on both. In the Hammer horror tradition, what emerges is an amalgamation of the former two, a multi-modal monstrosity uncanny in its convergence culture communiqué.

Discussion to be continued in Flow 22.03.

Image Credits:

1. Hammer Credits

2. TCM Logo

3. The Curse of Frankenstein (1957) Poster

4. The Mummy (1959) Poster

5. Peter Cushing in The Horror of Dracula (1958)

6. Christopher Lee in The Horror of Dracula (1958)

7. Nightgown vampire from The Horror of Dracula (1958)

8. Robert Osborne & Ben Mankiewitcz

9. TCM Presents Psycho Poster

10. Graham Humphries Hammer Horror Compilation

Please feel free to comment.

- Phillips, Kendall. Projected Fears: Horror Films and American Culture. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers, 2005. 8-10. [↩]

Pingback: Franchising Horror for Television Garret Castleberry / Oklahoma City University – Flow

Fun article! One piece of pedantry – the caption on the 3rd image should read ‘The Horror of Dracula’ (1958) instead of ‘The Curse of Dracula’ (which, if it exists, was not made by Hammer)

The story of Dracula is a very popular trend. I was in Transylvania and I saw his castle. I wrote about this in my essay uk.paperell.com , which I ordered here. I have long been interested in the history of Romania and the castles of central Europe.

I have thought so many times of entering the blogging world as I love reading them. I think I finally have the courage to give it a try. Thank you so much for all of the ideas!

i love to see movies of dracula. These movies reminds me the late 90s. I find your article so much informative and entertaining. writingmyessay.com is platform that can write about all stories of kids.