Mapping Media Retail in the Global Midwest: Dearborn, MI

Dan Herbert / University of Michigan

When I think of “flow,” I think materially and visually. I see masses in motion – cars on a freeway, groceries going past a register, rivers running, and the wind that suspends my kite. Given my research about video rental stores, I have thought a lot in particular about the ways in which both people and videos flowed into, through, and around these places. When I was composing Videoland, I often had the fantasy of making maps of all the video stores in the country at different historical moments, like snapshots of how these stores flowed across the landscape and then receded. Not surprisingly, I did not have time to produce such maps, and I doubt I could have found all the necessary information in any case.

But I have remained fascinated about how one might visualize the intersecting flows of people and video commodities, historically and geographically, and have begun making some maps that aim to accomplish this. Indeed, I am interested in exploring what mapping might afford scholars in film and media studies more generally, while also assuming that the problems and limitations of such an endeavor could be productive and lead to new research questions. Further, I have taken this opportunity to address two issues not fully covered in Videoland. First, I asserted that video stores “localized” video culture, meaning that they offered geographically convenient access to a relatively wide selection of movies and consequently allowed communities to shape their own place-based movie culture. However, much of the support for this argument derived from interviews conducted between 2009 and 2012, and I have been eager to provide some concrete historical support for this claim. Second, I have wanted to examine video store culture in relation to issues of race and ethnicity, which my book does not really do.

To address both these issues simultaneously, I have examined the number and location of video stores in some towns in the American Midwest that either have significant populations of ethnic minorities or where there has been a notable change in the ethnic composition. I chose these towns, at least in part, because the Midwest is not conventionally considered “global” and yet this region is global in many respects; in this instance, we see that the Midwest is characterized by a global flow of people and media commodities.

I gathered the addresses for the stores from city directories published by R.L. Polk & Co. I also collected data regarding the locations of bookstores, record shops, and movie theaters in order to gain some sense of how the video stores fit within larger entertainment retail environments. Additionally, I gathered census data for the areas in question in order to have these maps indicate demographic information. The final maps were produced with the assistance of Ben Strassfeld, a graduate student in my department of Screen Arts & Cultures at the University of Michigan who is particularly skilled with ArcGIS software.

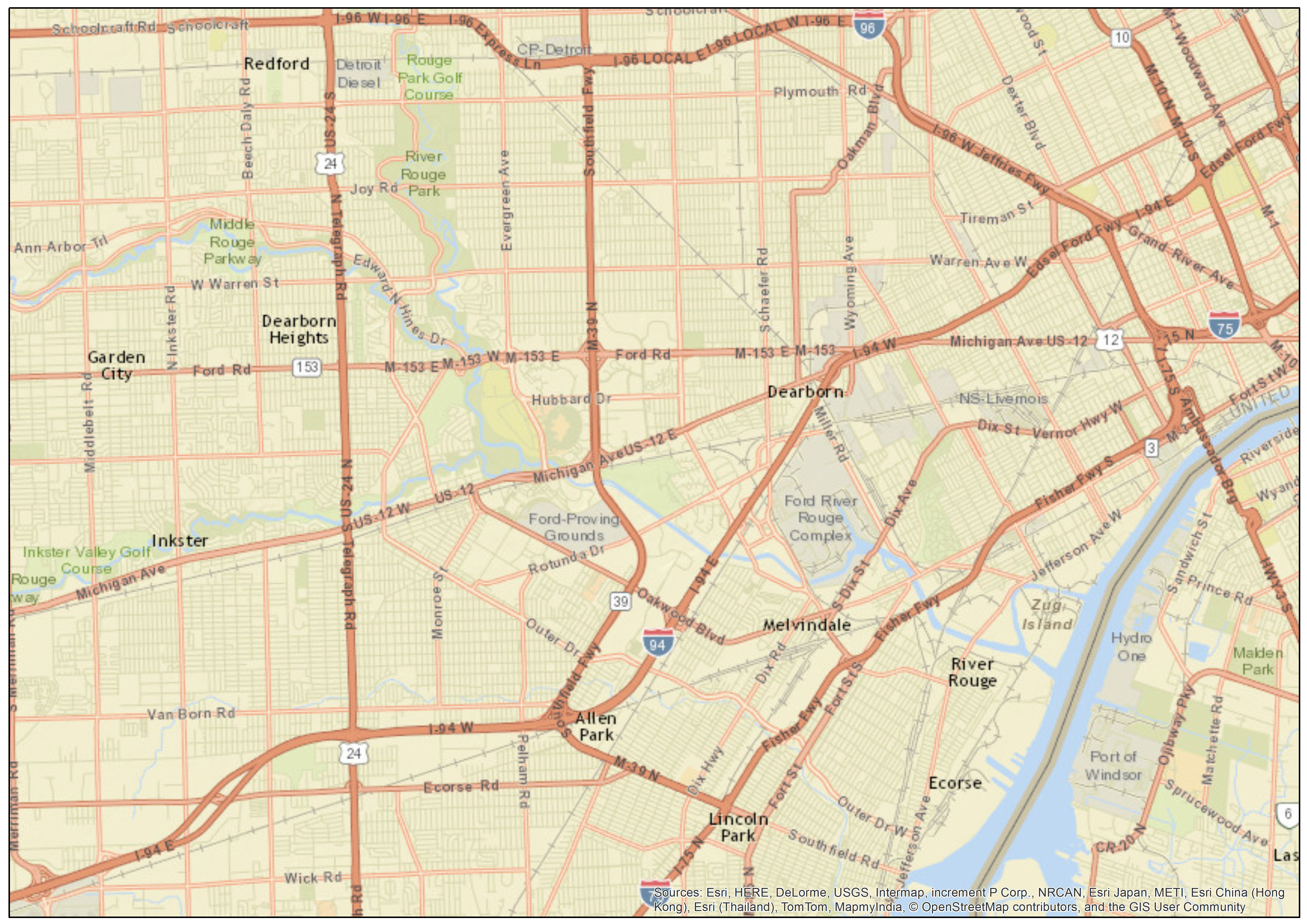

The first town I examined is Dearborn, Michigan, a suburb on Detroit’s southwest border. It is famous for being the location of the headquarters of the Ford Motor Company and the company’s immense River Rouge Complex. Presently, Dearborn has a population of nearly 100,000 people, who are largely working class. The town is notable for having a relatively large Arab American population, a community that has been in the area for over one hundred years and which has grown significantly since the second half of the twentieth century.

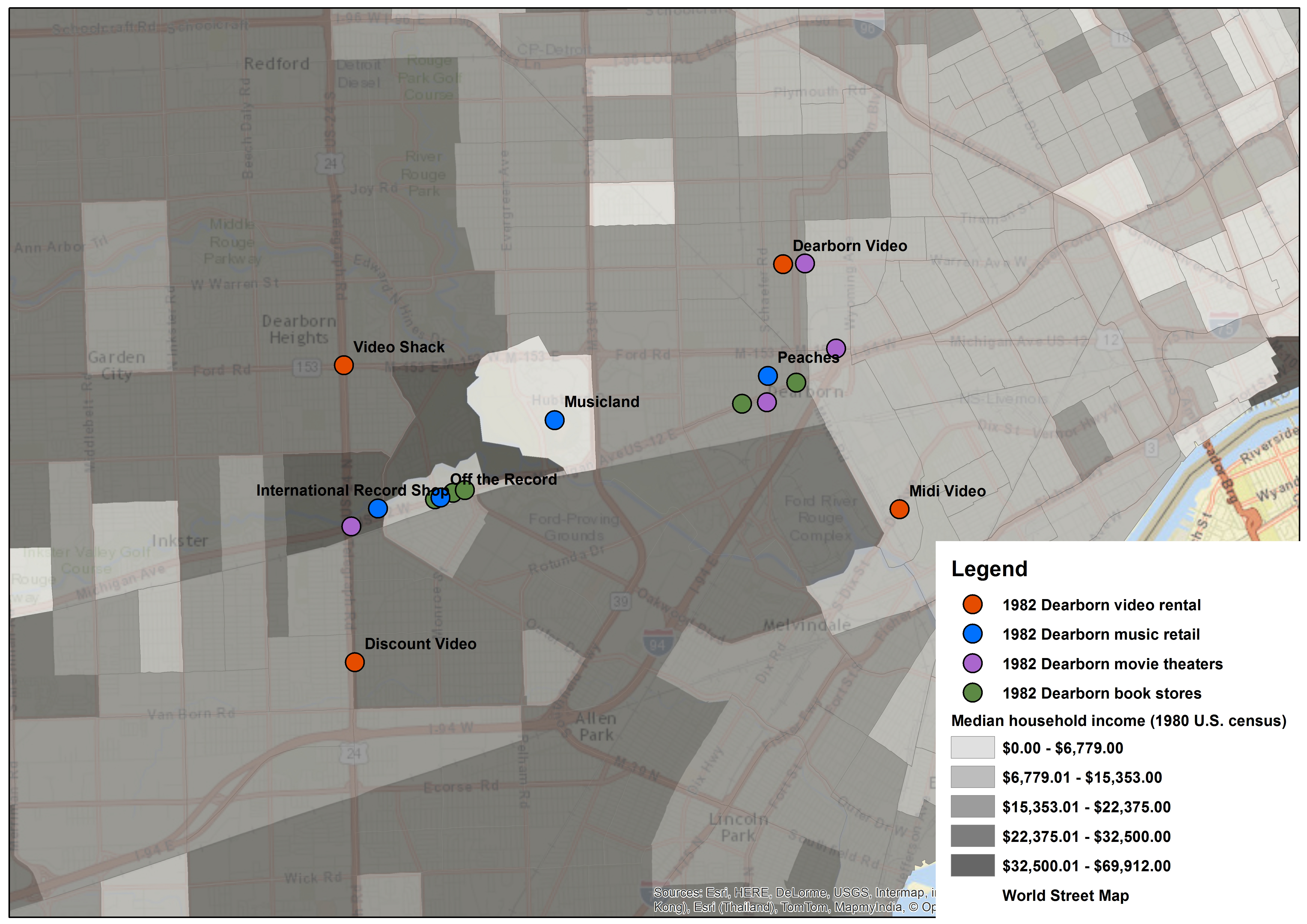

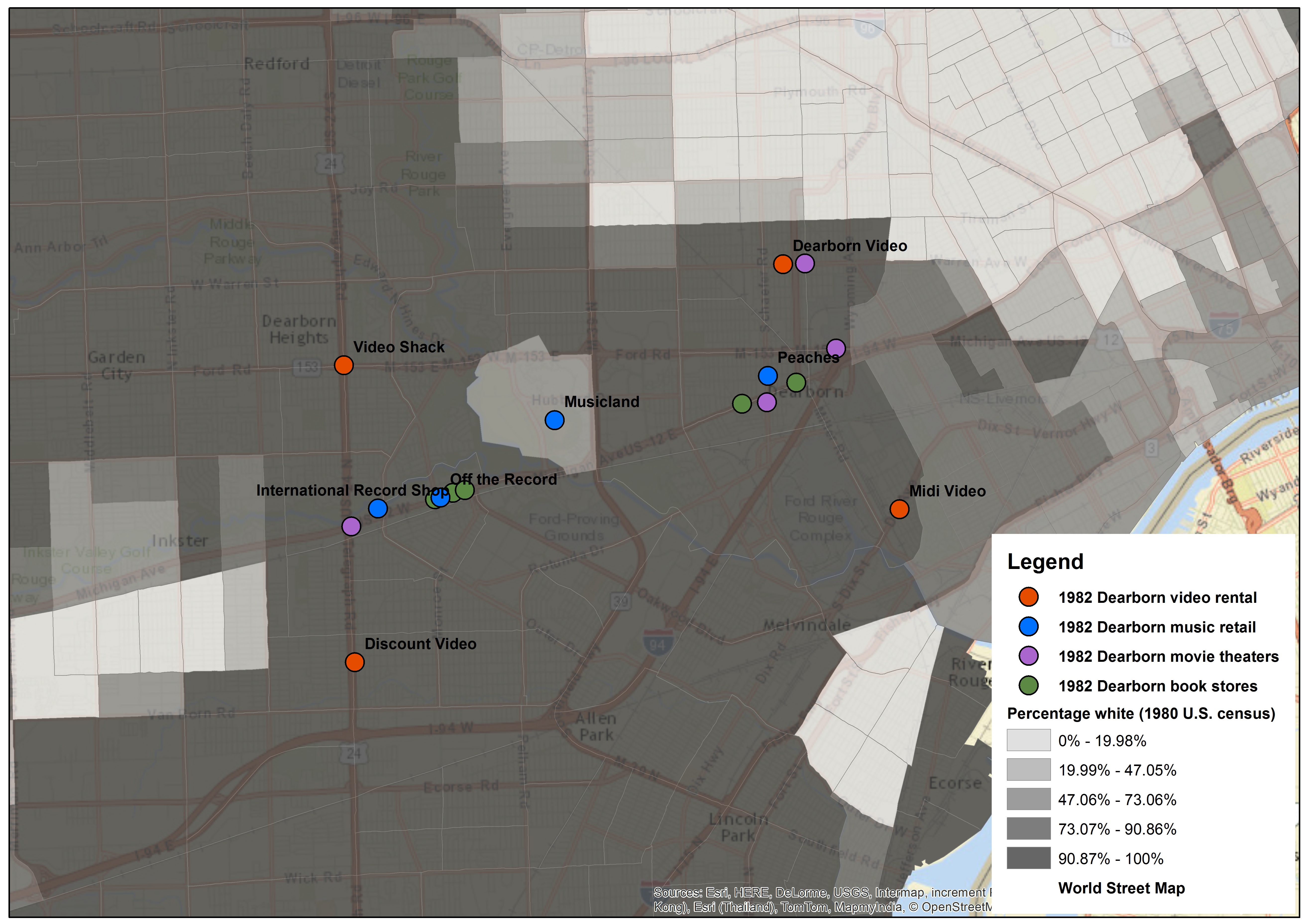

This first map (Figure 1) shows the location of video stores in 1982 and the shading indicates household income. Immediately, we see that although there is a commercial corridor (Michigan Avenue) where one can find the majority of bookstores, record shops, and movie theaters, the video stores are comparatively decentralized. This suggests that, in fact, video stores were more “localized” in this town than other retail sites, to the extent that the video stores were more embedded within neighborhoods.

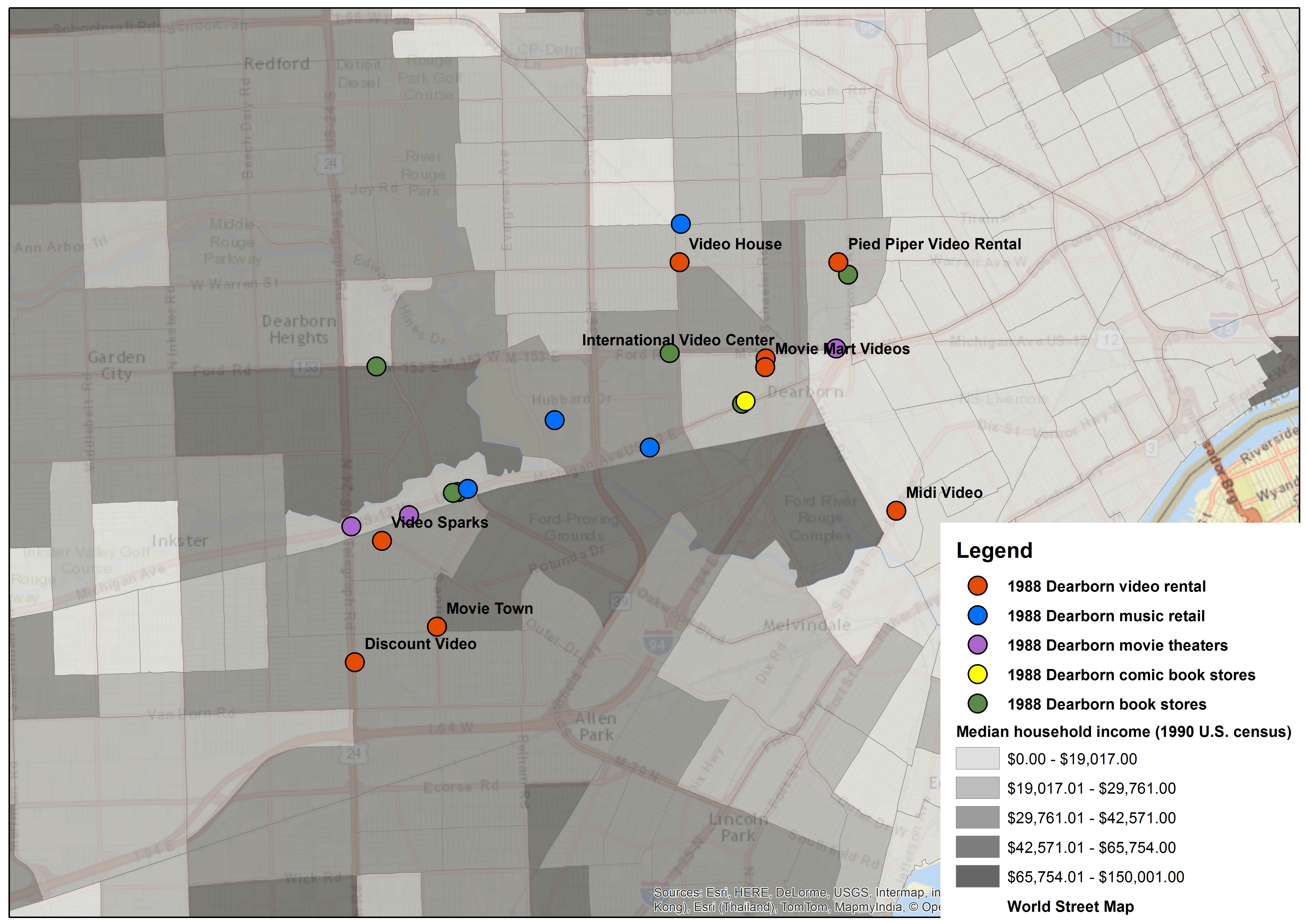

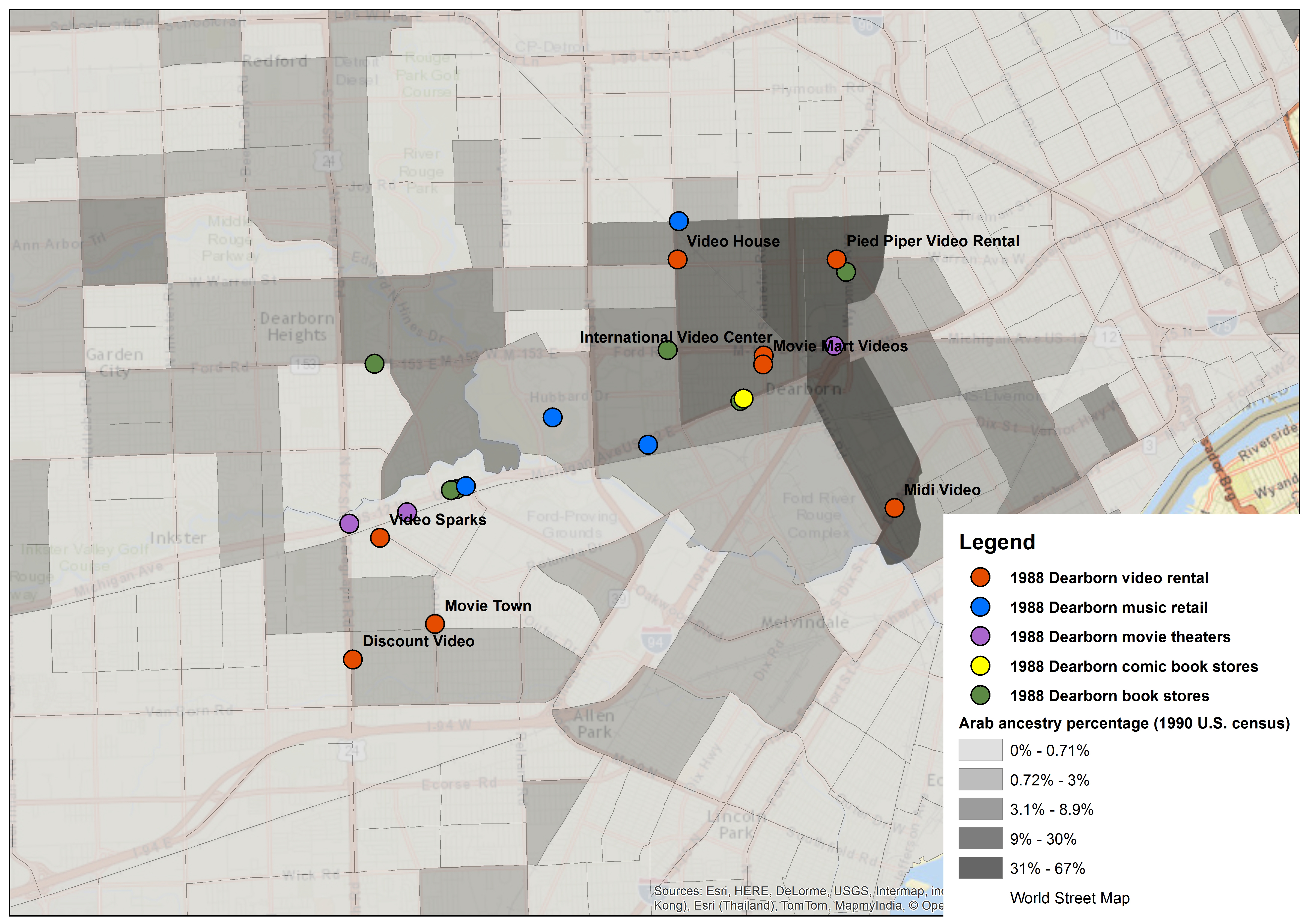

Moving forward to 1988 (Figure 2), we see an growth in the number of video stores, which is unsurprising given the way the larger home video industry developed during this period. We also see that these stores continue to be located in a dispersed fashion. Although we see that bookstores and record stores are similarly located some distance away from one another, these sites generally stick to the main commercial strips.

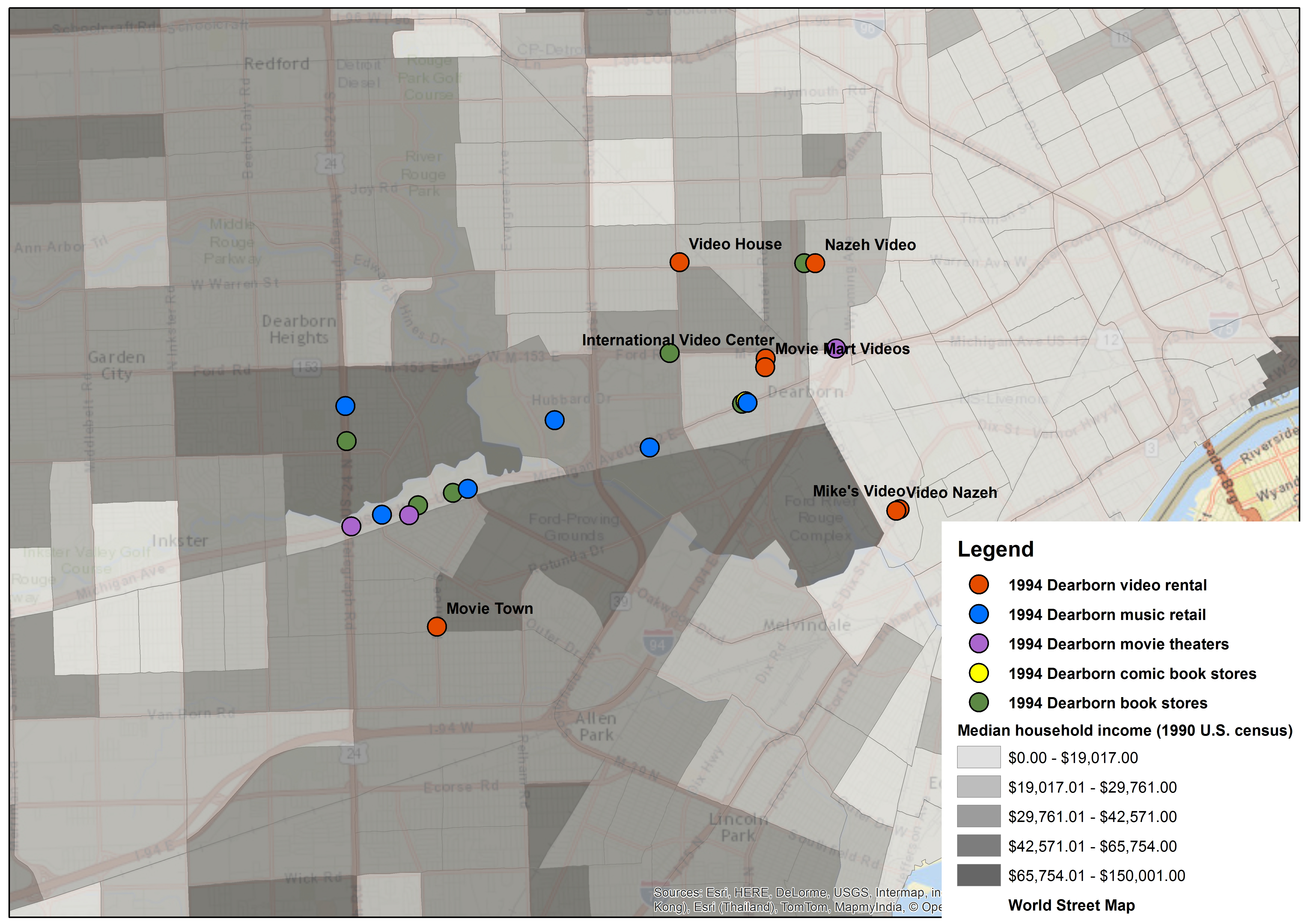

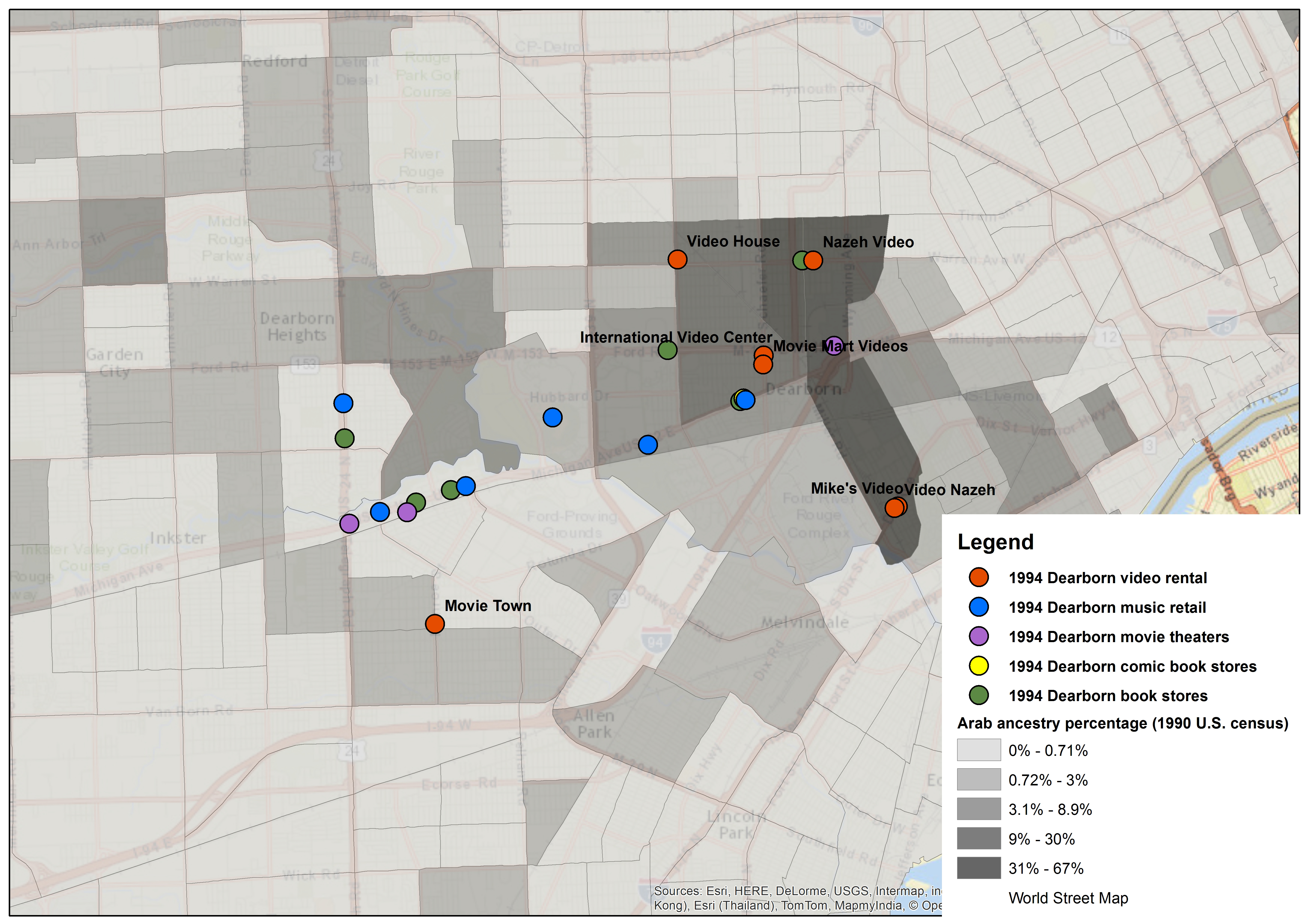

When we move to 1994 (Figure 3), we see a slight reduction in the number of video stores as well as the persistence of a corridor of other entertainment retail sites. Generally, we see no correlation between income level and the location of any of these retail locations.

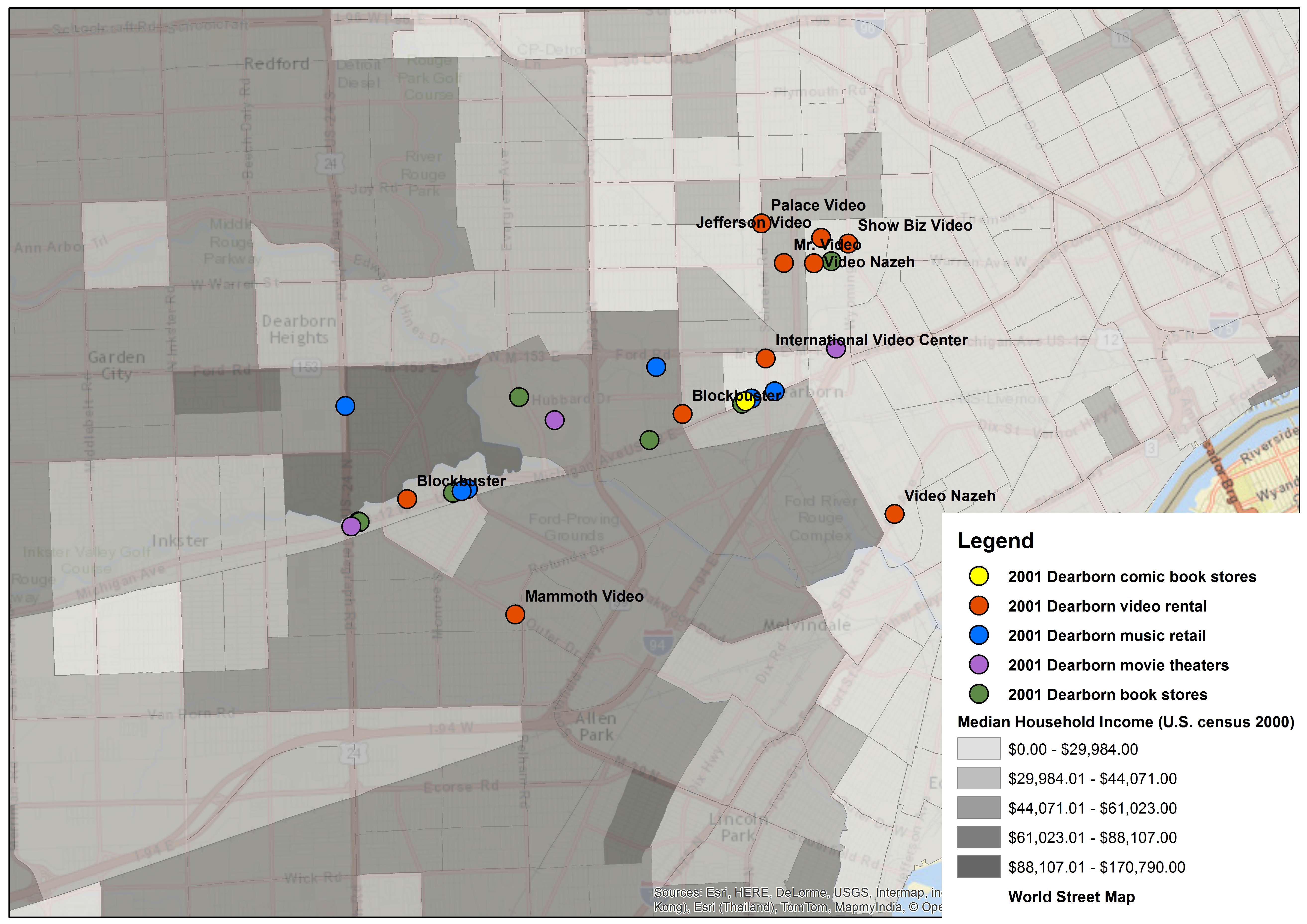

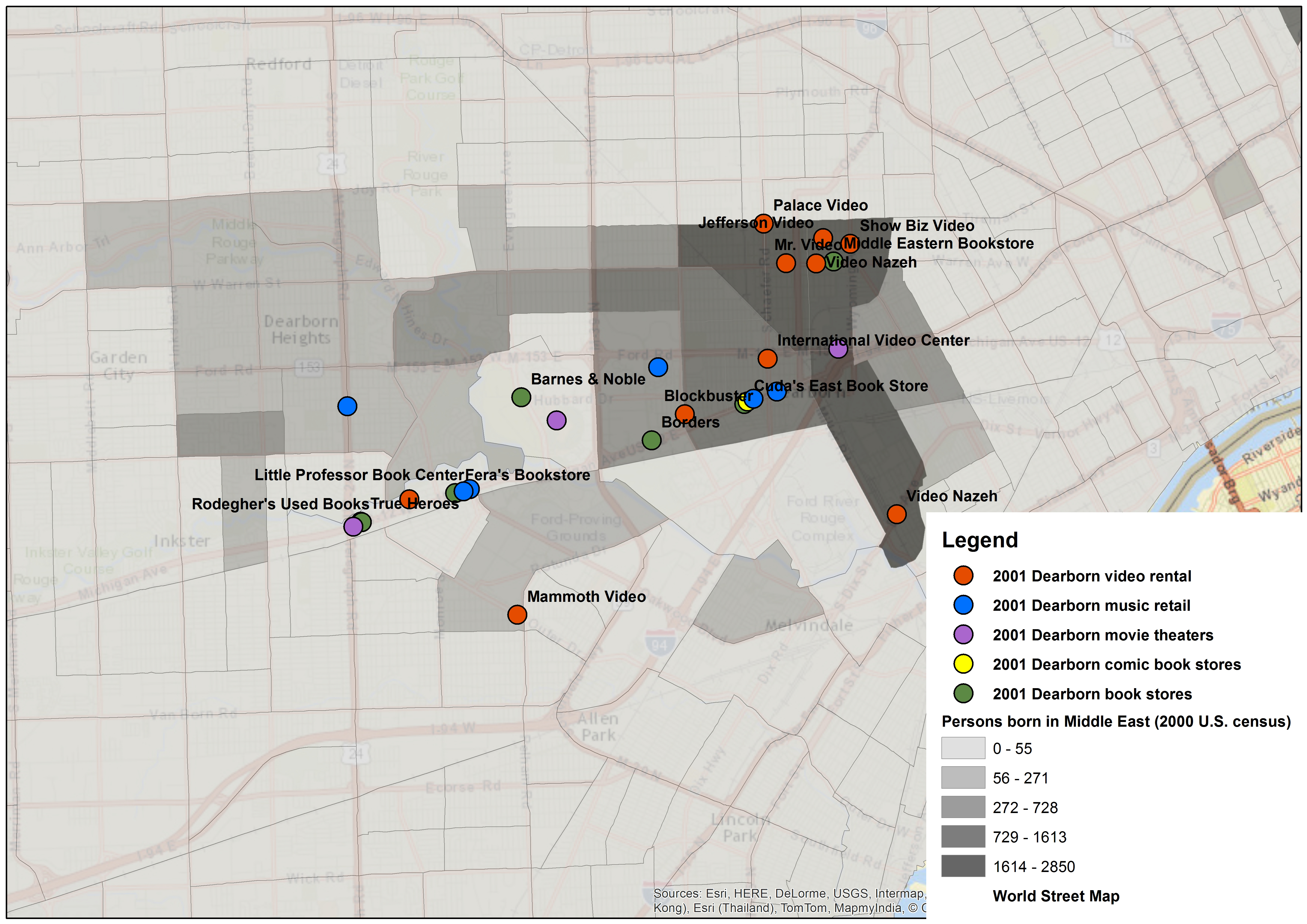

Unfortunately, I was only able to gather data through 2001. Nevertheless, the map for this year is very striking (Figure 4).

First, we see a general reduction in income levels, especially when compared to 1988 levels. Second, we see the persistence of the commercial corridor along Michigan Avenue and that book stores, record stores and movie theaters remain on this line. We also see the appearance of two corporate video stores, both Blockbuster Videos, and unlike the independently owned stores these are located on the Michigan Avenue strip. But the third and most striking element of this map is the cluster of video stores in the northeast part of the town. This clustering defies the previously demonstrated distribution of video stores in the area.

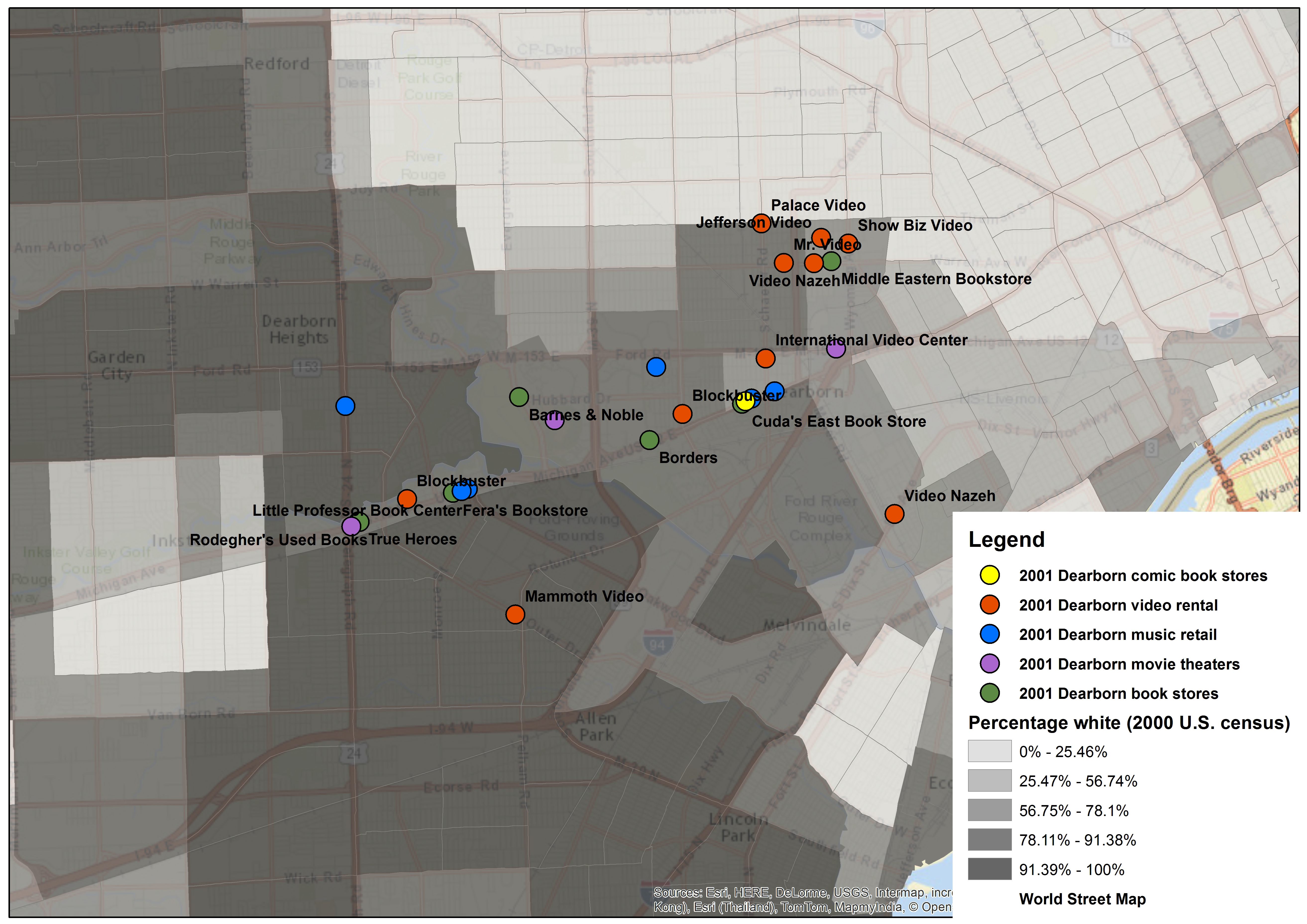

If we switch the demographic information to represent race, looking specifically at the location of Caucasians in 1982 and 2001 (Figures 5 and 6), we see no correlation with the location of the video stores, just as there was no correlation with household income.

However, if we change the maps to represent Arab ancestry, and look at the maps for 1988, 1994, and 2001 [Figs. 7, 8, and 9], there appears to be an explanation for the clustering of the video stores; at the minimum, there appears to be a strong relationship between the location of people with Arab ancestry and a number of video stores in the area.

Indeed, these maps indicate the existence of a vibrant commercial district within the Arab American community and, further, suggest that this population was particularly supportive of independently owned video stores. Some of the stores’ names also suggest this relationship, such as with International Video Center and Video Nazeh; note that the Middle Eastern Bookstore is also located in this district.

Although these maps strongly suggest that these video stores, and some other retail sites, served as de facto cultural centers for Arab Americans in the area, they also have some significant limitations that merit consideration. First, the maps are unable to indicate these stores’ actual patterns of use; that is to say, they cannot indicate what videos these stores held, how often particular titles were rented, or to whom. Second, and extending from this, the maps are unable to indicate where the customers for these video stores actually came from. Although it is likely that these stores were primarily used by people living nearby, they could well have been serving people, Arab American or otherwise, that drove a greater distance to rent their tapes. For instance, I did not map the location of video stores in Detroit, just to the north, and it could well be that people in Dearborn rented tapes in Detroit and vice versa. In these two ways, we see that these maps indicate some sorts of “flow” but not others.

Third and finally (for the moment), these maps depend crucially on the ways in which the city directories define retail spaces and the ways in which the census defines human beings. Thus, video rental could have been happening in this area prior to 1982, at electronics shops, record stores, etc., but the directories had no specific category for “video rental” until that year. Simultaneously, the census’ racial, ethnic, and national categories are both essentializing and homogenizing, where in fact peoples’ individual and communal identities are much more fluid and hybrid. In this respect, the maps rely on information that is problematically fixed, somewhat analogously to the way in which they present dynamically changing social, cultural, and economic flows in a static form.

These problems aside, another major issue of this work is the extent to which the example of Dearborn, Michigan is representative or generalizable. It seems to me that the way in which this Arab American community made use of video rental stores could very well be a local phenomenon. Another social group in another town could indicate very different patterns of cultural and economic activity.

Next stop, Elkhart, Indiana.

Special Thanks: I am indebted to the Institute for the Humanities at the University of Michigan for grant funds distributed through the Humanities Without Walls consortium “Global Midwest” initiative. HWW is a Mellon-funded initiative under the leadership of Dianne Harris of the Illinois Program for Research in the Humanities at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Many thanks to the larger research team of Richard Abel, Kathryn Brownell, Phil Hallman, Johannes von Moltke, and Greg Waller, whose comments and associated projects influenced my work significantly. Yuki Nakayama and Dimitri Pavlounis provided helpful feedback as well. Thanks again to Ben Strassfeld for making the maps.

Image Credits:

1. Dearborn, Michigan (author’s personal collection)

2. Figure 1: 1982 Dearborn, MI Video Store Locations (image made by Ben Strassfeld, provided by the author)

3. Figure 2: 1988 Dearborn, MI Video Store Locations (image made by Ben Strassfeld, provided by the author)

4. Figure 3: 1994 Dearborn, MI Video Store Locations (image made by Ben Strassfeld, provided by the author)

5. Figure 4: 2001 Dearborn, MI Video Store Locations (image made by Ben Strassfeld, provided by the author)

6. Figure 5: 1982 Dearborn, MI Caucasian Residents’ Locations (image made by Ben Strassfeld, provided by the author)

7. Figure 6: 2001 Dearborn, MI Caucasian Residents’ Locations (image made by Ben Strassfeld, provided by the author)

8. Figure 7: 1988 Dearborn, MI Arab Residents’ Locations (image made by Ben Strassfeld, provided by the author)

9. Figure 8: 1994 Dearborn, MI Arab Residents’ Locations (image made by Ben Strassfeld, provided by the author)

10. Figure 9: 2001 Dearborn, MI Arab Residents’ Locations (image made by Ben Strassfeld, provided by the author)

Please feel free to comment.

Fascinating media geography project, Dan!!