Teach-Ins and Twitter

Michael Newman / University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

The first teach-in was held at the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor in 1965, and the -in came from the sit-ins at lunch counters and other segregated public places in the 1950s and 60s where African-Americans demanded equality. It was organized by professors who gathered up members of the campus community to protest the Vietnam War by teaching about the conflict, an alternative to a work stoppage. A teach-in was to be “a shrewd means of energizing the university without disrupting it.”1 The overnight event was attended by thousands of students and hundreds of professors. It was covered in the national news.

Many more teach-ins were staged on college campuses during these tumultuous years when universities were at the center of movements for social justice and New Left politics. They were thought to make many students who had not been paying much attention to foreign affairs conscious of America’s involvement in Vietnam. A teach-in at Berkeley attracted as many as 30,000 participants (such estimates being contentious) and was a bona fide media event, with folk singers and well-known figures like Dr. Benjamin Spock and Norman Mailer. It was broadcast on the radio. There were also pro-war teach-ins, but whatever ideas were conveyed, the key purpose of a teach-in was nonviolent demonstration through pedagogy, building a platform for public intellectual discourse. Faculty and students along with members of the public could engage politically within the space of the university, and the university gave legitimacy to dissent over the war.

One statement at a 1965 teach-in provoked a huge controversy over academic freedom and political speech. Eugene D. Genovese, a history professor at Rutgers University, spoke these words at a teach-in on his campus: “Those of you who know me know that I am a Marxist and a Socialist. Therefore, unlike most of my distinguished colleagues here this morning, I do not fear or regret the impending Viet Cong victory in Vietnam. I welcome it.” This was quoted in the papers, and became an issue in the New Jersey gubernatorial race when the challenger called on the sitting governor to fire Prof. Genovese. In this instance, the academic freedom of an outspoken critic was protected when Rutgers’ president and Board of Governors took no action against him.

Teach-ins have not been common for several generations, but the engagement of university students and faculty in political debate perseveres, and in some ways it has a more public presence than it ever did. As they have for years, critical scholars speak publicly, appear on television and radio, and write for mainstream media outlets. But few platforms have the real-time immediacy of twitter, or its potential to become the grounds for controversy. Twitter is a polarizing medium. Its ardent users really get it, and use it in ways that outsiders find irritating, confounding, or nonsensical. Twitter is many things for many people, but one way it is being used is very similar to the teach-ins of the 1960s. It is a platform for academics’ social and political criticism, with an often broader potential for spreading dissent than can be contained in a campus auditorium. But the same public soapbox that twitter represents as a place for critical opinion, commentary, and information is also a bright potential target for the outrage machines seeking offending statements to call out.

The most famous case of this is Steven Salaita, and the tweets at the middle of his ordeal are, like the statements of the Vietnam protests, about a war that should be of concern to all Americans. The Israel-Gaza conflict in the summer of 2014 may have shed no American blood, but our government’s policies in the Middle East mean that we are never disinterested bystanders to clashes between Israelis and Palestinians. Salaita, who was hired to teach at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign beginning in Fall 2014, tweeted passionately and with great urgency and anger about a catastrophic Israeli military assault.2 Salaita was “unhired” during the summer of 2014 as a consequence of his tweets on the war and Israel’s occupation of Palestine, and his legal action against the university is ongoing.

He is not the only scholar whose tweeted statements on matters of public concern have drawn chilling responses from right-wing media as well as campus leaders. Saida Grundy, recently hired to teach at Boston University, faced conservative outrage over tweets she wrote about racial politics and American history, particularly for calling out white people. Sara Goldrick-Rab, a professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, was similarly targeted for a tweet describing a conversation with her grandfather, who saw similarities between our Governor Walker and Adolph Hitler, and calling Walker and Republican lawmakers fascists, as well as tweets at undergraduates about the situation in the UW System suffering cuts and changes to tenure and shared governance. It can hardly be random that those singled out for their critical, so-called offensive views are often women and people of color.

Twitter seems to invite clashes of contexts, and as a platform for dissent and public pedagogy, it has clear virtues and limitations. To members of a community within the world of twitter, who engage with one another on a regular basis and share each other’s codes and references, twitter can sustain remarkably vigorous discussion and debate. The short character limit is a constraint (though it also makes for succinct writing), but detractors often miss the crucial point that you can tweet more than once. Twitter is a constant flow of ideas among communities just as much as it is a collection of very brief expressions by individuals. It’s also a medium typically used for conversation rather than polished, edited prose. To outsiders, however, tweets are easily excerpted from the flow, abstracted from their context, and run up the flagpole as banners of transgression. They said WHAT!? Because twitter is so public, and tweets are so easy to quote and embed in stories, the public intellectuals using it are taking huge risks. This isn’t always good for movements critical of the current power structures, and yet it does help to spread a message. The potential for public pedagogy in scholarly tweets is promising but there can be unreasonable costs.

And these costs can only be managed if our universities rededicate themselves to the fundamental values of shared governance and academic freedom. If only the leadership of the University of Illinois in 2014 had shown the same judgment as the Rutgers administrators and Governors in 1965. Much has changed since then, but one undeniable factor has to be the shrinking investment of the state in public education, and the privatization and corporatization of academe. The influence of pro-Israel donors on the UIUC administration and the Board of Trustees was undoubtedly a cause of Salaita’s unhiring.

My own University of Wisconsin System — where I earned two degrees and have taught for 18 years — has been one prominent example of a public institution weakening its academic freedom protections as its transforms from a thriving public trust into a corporatized and privatized shadow of itself. To be nimble, flexible, efficient, etc., our masters in state government, abetted by a friendly Board of Regents appointed by a very conservative governor, have dramatically diminished the faculty’s rights. In place of the nation’s strongest tenure and shared governance protections enshrined in state statute we have new conditions wherein layoffs can be made in the event of academic program changes imposed from on high. This weakening of our position might seem disconnected from the contemporaneous outrages over Salaita and other outspoken tweeting profs. They are actually part of the same political process of curtailment of the freedom to do critical or controversial work in higher education. Who on a UW System campus will feel free to speak out against an Israeli (or American) war, or will sustain research programs on stem cells or climate change, or will have confidence to criticize an administration’s complicity in shifting the costs of education from the public to the individual? Why would we feel confident that administrators will protect us?

Under current conditions, all kinds of pedagogy are under threat — our work in the traditional classroom as well as the public discourse of blogs, tweets, Facebook updates, Chronicle columns, and whatever else we do to share our knowledge and insight online or off. A real university needs not just to tolerate but to incubate critical, unpopular, and controversial ideas. The teach-ins of the 21st Century, whatever forms they assume, will need the freedom even to outrage.

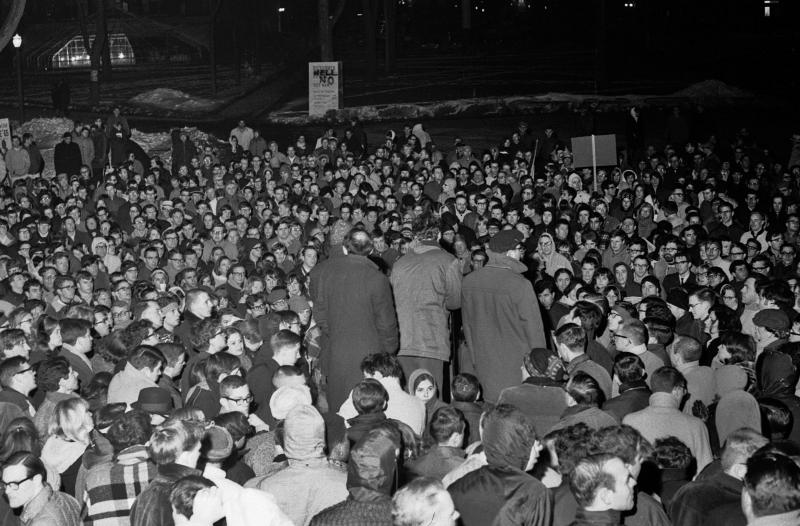

Image Credits:

1. Vietnam War era Teach-in, March 1965.

Please feel free to comment.

Pingback: Teach-Ins in the Time of Trump - Top 10 RSS Feeds | Follow the Most Popular RSS Feeds