I Love the 90s…and so does the post-network television industry.

I Love the 90s…and so does the post-network television industry.In just the last couple weeks, several new television productions have been announced that suggest the network plundering of the 1990s is now fully underway as a concrete production cycle.

Fox has announced that it will produce a 6-episode limited series of new

X-Files episodes with Gillian Anderson and David Duchovny returning to their original roles. In a move I suspect far fewer saw coming,

NBC has resurrected the football-themed sitcom

Coach, apparently unable to imagine keeping Craig T. Nelson off its schedule after the recent cancellation of

Parenthood. The Disney Channel had already drawn from ABC’s old TGIF programming block to bring back

Boy Meets World as

Girl Meets World in 2014, and now Netflix wants to do the same in

reviving Full House as

Fuller House. With this reinvestment in 1990s television properties come accompanying reports about the difficulties of executing that strategy; David Lynch has apparently

parted ways with Showtime despite their once shared desire to update

Twin Peaks for the 21st Century, and the overall future of the project remains in doubt. Nevertheless, even struggles to mine the 1990s for renewable resources call our attention to the lengths to which programmers are going to extract new value from the television of that era. Despite all the changes wrought by the post-network era, networks, cable channels, and over-the-top digital services alike can all comprehend the future as yet another extension of old broadcast programming.

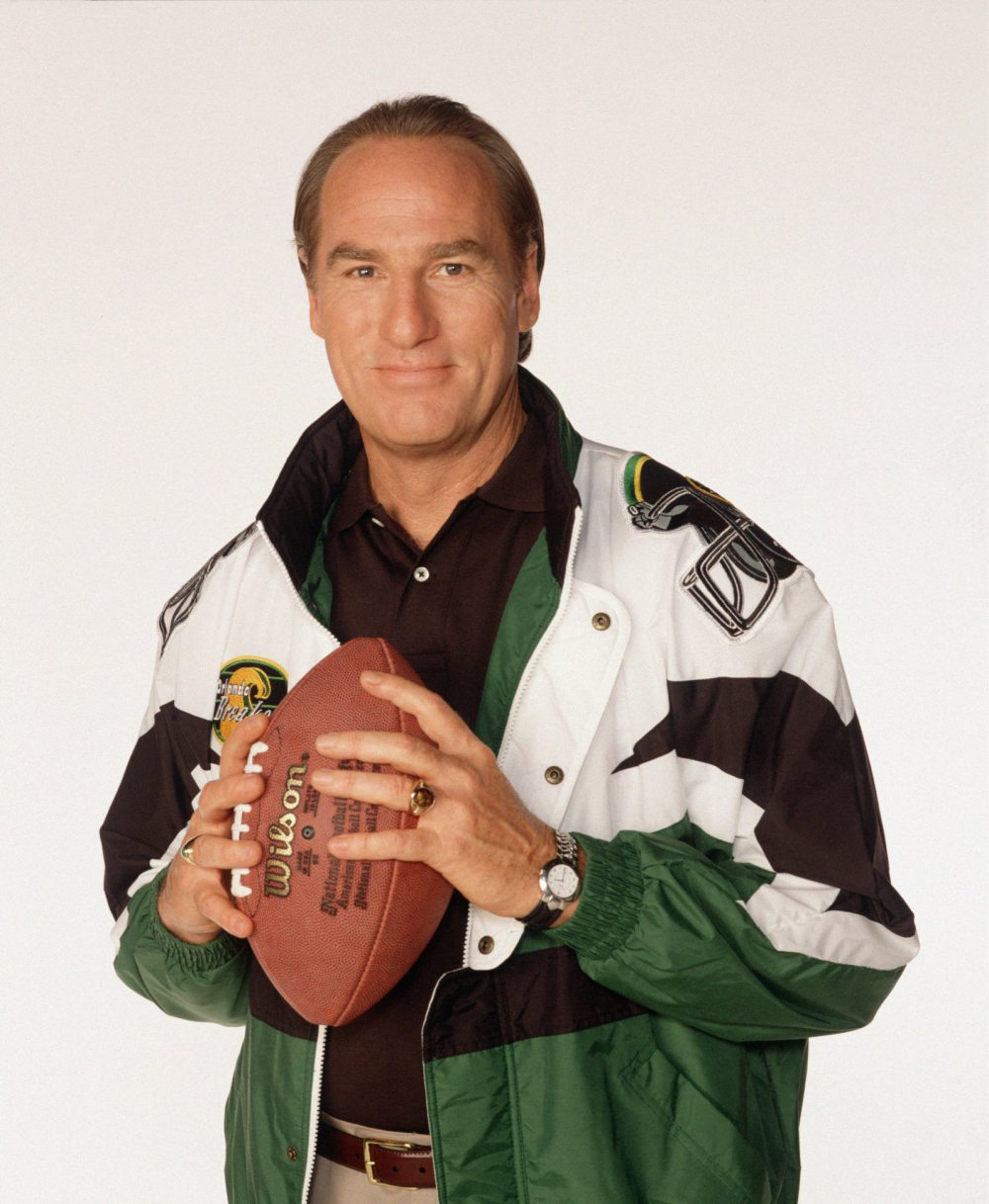

Craig T. Nelson returns as Coach Hayden Fox on Coach

Craig T. Nelson returns as Coach Hayden Fox on CoachWe’ve had recent waves of 1970s and 1980s revivals as well, so it shouldn’t be all that surprising to reach this point with the 1990s. But I’ve been trying to reflect on what the programming of the 1990s specifically might have to offer contemporary television from network to Netflix, and whether this nostalgic storytelling is a new moment in television franchising or just more of the same.

In my all-time favorite Flow column, Bob Rehak examined the 2003-2009 Battlestar Galactica series as an exemplar of the “reboot” strategy whereby the television industry continually renews and reinvents its proven properties to pitch them at new audiences in different cultural moments. Rehak understood the “reimagining” of Battlestar for the 21st century less as the force of cultural zeitgeist, however, and more as part of the “rhythms of franchise.” Regardless of cultural change, remakes and relaunches are part of the industrial process of maintaining and managing the serial production of television franchises over time. “Such is the nature of the successful media franchise,” Rehak wrote, “doomed to plow forward under the ever-increasing inertia of its own fecund replication.” I’ve sometimes taken issue with the bleakness this implies; rather than “doom,” another way to think about this is how franchising may be just as reliant on innovation and dynamism (even if only in small doses) than formula and creative stasis. Regardless, from his vantage point in 2007, Rehak helps us to see how the serial processes and temporalities of television franchising in the first decade of the century pushed toward continual narrative reinvention.

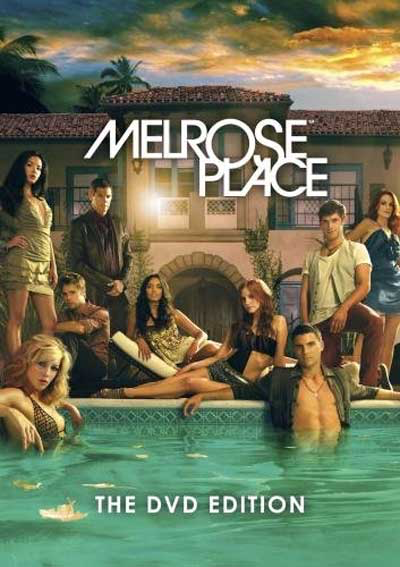

I wonder if this cycle of 1990s nostalgia represents a move away from the logic of the rebooted reinvention. Yes, the industry is going back to the well in a familiar way, but instead of reboots we are seeing revivals. We aren’t seeing young, fresh reinterpretations of Mulder and Scully or even Uncle Joey; instead, we’re going back to continue what was started and (it now seems) left unfinished in the 1990s with the original interpretations of the characters. I’m not suggesting this move is unprecedented or even particularly new. Beyond the occasional reunion show in the past, we’ve seen television writers pick up the storylines of long lost characters on dramas like the recent 90210 and Melrose Place on The CW, as well as the Dallas revival on TNT. Yet in these cases, the returns of Jennie Garth, Laura Leighton, and Larry Hagman as their original characters (Kelly Taylor, Syndey Andrews, and JR Ewing, respectively) each seemed to be as much as part of a process of torch passing to a new generation of characters who share narrative focus or even come to be the new focus. While these current slate of 1990s revivals remain in pre-production, and I’m sure new elements and characters will be announced in the future, the initial hype surrounding them has very little to say on what new might be brought to the table. The only things disclosed about either X-Files or Coach focus on the casting of familiar returning leads—and likely very little other casting has yet been done to disclose. These programs are being ordered straight to series without pilots on the basis of the old that’s being revived, not the new of reinvention.

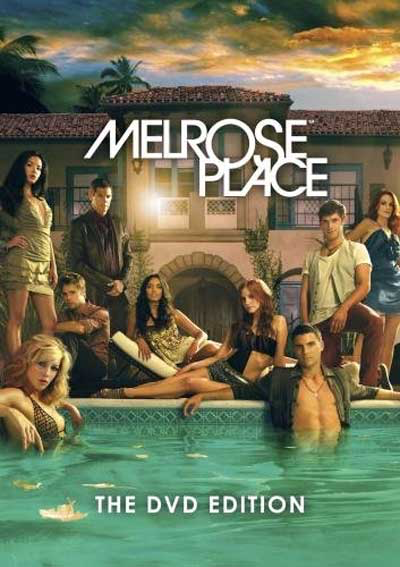

Dr. Michael Mancini (Thomas Calabro) and Sydney Andrews (Laure Leighton) stand in the background to support a new cast of Melrose Place tenants in the 2009 series.

Dr. Michael Mancini (Thomas Calabro) and Sydney Andrews (Laure Leighton) stand in the background to support a new cast of Melrose Place tenants in the 2009 series. If this programming trend does constitute a move away from the reimagining and the reboot, I continue to wonder what factors might be driving such a shift. My critical eye might be compromised here, as I’m personally fascinated by these revivals. I’m thrilled to see the media industries invest more in television revivals on television; as a fan, I would have much rather seen properties like

Firefly and

Veronica Mars revived as ongoing series (even limited like

The X-Files) than one-off films. I am also compelled by the chance to revisit a handful of television worlds that I watched when coming of age as both a viewer and budding television scholar in the 1990s. In my daily, stripped viewing of it,

Coach is literally the lens through which I came to think about and appreciate syndication and repetition; along with the

Star Trek spin-offs of the 1990s,

The X-Files introduced me to fandom (though I never cared for

Full House). So as much as I should be suspicious of both my complicity in the ideology of nostalgia and the industry’s ability to pull these off in a satisfying way, I am a little gleeful nonetheless. But if only because I’ve considered the possibility of other parts of this 1990s television heritage being revived—it won’t be a true return to the 1990s, in my opinion, until there’s another

Star Trek in production—I keep wondering what industrial purposes the revival of such series serves.

Michael Dorn can’t get studio support for his “Captain Worf” Star Trek pitch.

Michael Dorn can’t get studio support for his “Captain Worf” Star Trek pitch.Has the availability and repeatability of programming on Netflix and Amazon Prime reshaped the temporalities of viewing in such a way that older interpretations of television narratives have become (perceived as) more marketable than rebooted reinventions? As the temporalities of access to older programs change because of these new viewing platforms, has it become difficult for the industry to imagine separating viewers from their interests in these original incarnations? Is there an economic imperative to produce new, narratively compatible content that can be packaged along with existing programming libraries on these subscription services for

dissertation help (or in other venues of repetition like

TV Land?). In restarting production of

Star Trek as

Star Trek: The Next Generation after a 20-year hiatus, for example, Paramount Television reasoned that even if the new series was a failure, it could simply be added to the syndication package of the original, thereby increasing the value of that package. Forbes has suggested a similar dynamic may be in play on

Netflix.

The NetfliX-Files

The NetfliX-FilesAt the same time, might there be anything about the nature of 1990s television narrative and its embrace of “cumulative,” hybrid episodic-serial structure that makes a greater demand for revival and in-continuity follow-up?

Twin Peaks,

The X-Files, and yes, even

Coach played with ongoing storylines that helped usher in new kinds of narrative norms in US television by the end of the 1990s. And each of them also experimented with “soft” reboots in their final seasons:

Twin Peaks tried to move on from the mystery of Laura Palmer’s killer,

X-Files introduced new lead agents, and

Coach moved Hayden Fox from Minnesota college football to a pro team in Orlando. Maybe the push toward reinvention already contained within these cumulative forms—and the failure of those original reinventions to stave off cancellation—has led to more of a back-to-basics embrace of familiarity over reimagining.

As noted above, the Star Trek spin-offs remain a particularly interesting point of comparison, both in representing an earlier moment of in-continuity revival, and in being persistently absent from the current nostalgia party. The obstacles standing in between Star Trek and a television revival are too numerous to name here, but its worth noting that over the years Next Generation stars like Jonathan Frakes and Michael Dorn have expressed interests in returning their characters to television production. While such revivals will probably remain pipedreams for them, they have somehow materialized for many of the other television series over here https://grademiners.com/book-report of that same era. Who would have guessed that in 2015 Coach would become a more easily exploited franchise than Star Trek—and how does it underscore the real industrial and cultural shifts that must have occurred since the 1990s for this to happen?

Image Credits:

1. I Love the 90s…and so does the post-network television industry.

2. Craig T. Nelson returns as Coach Hayden Fox on Coach.

3. Dr. Michael Mancini (Thomas Calabro) and Sydney Andrews (Laure Leighton) stand in the background to support a new cast of Melrose Place tenants in the 2009 series.

4. Michael Dorn can’t get studio support for his “Captain Worf” Star Trek pitch.

5. The NetfliX-Files

Please feel free to comment.