Industry Lore and Algorithmic Programming on Netflix

Nick Marx / Colorado State University

Over the last several years, much digital ink has been spilled on Netflix, its allegedly slavish devotion to data, its stubborn refusal to make any of that data public, and its plans for world domination. In the absence of conventional metrics for comparing it to linear television networks, we’re left to cobble together incomplete findings from third-party research firms and infer broader generalizations about Netflix instead. We’d be lying if we said this two-part column isn’t grasping at the same straws, but we hope to reframe some of the available information about Netflix in order to avoid characterizing it as a “red menace” or something inherently threatening to television’s business-as-usual. Doing so can help critics and scholars better understand the context for Netflix’s success and its role as a cultural forum.

Despite growing concerns that Netflix’s algorithm-driven model will replace organic culture with cold, T-1000 ruthlessness, data may well serve to activate new sets of creative possibilities instead. TV producers have always worked within a set of industry constraints. Historically, these have been based on a body of common sense drawn from a combination of passed-down lore and information derived from highly flawed statistical services such as those offered by Nielsen. Working within these limitations, moments of immense creativity emerged, as did a long list of uninspired, derivative drivel.

The Netflix-led “Data Era,” we suggest, promises not to be all that different. Although new data gathering methods may well improve audience-targeting practices, such improvements amount to little more than new industry lore informed by more precise, but not necessarily more useful, information. As a result, new programming possibilities may well open up, with executives now being able to see virtue in unusual connections and combinations that once would have been perceived as nonsense. But how can we better conceptualize this balance of agency and machinery? If we posit at the least a soft connection between data and programming for dissertation help, what does this say about the nature of innovation and creative choice-making? The first part of this column explores the former question, the second, the latter question through a close look at the Netflix original comedy series BoJack Horseman.

Popular press accounts love to portray Netflix content as mostly the product of complex computer algorithms, but it’s important to remember the people interpreting those data, and how they do so differently from linear television. Generally speaking, Netflix’s structure for the relationship between entertainment products and data about them combines human intuition for knowing how to talk about and appreciate media content with a sophisticated system for organizing that content into categories as uniquely customized for a given subscriber as possible. For instance, Netflix employs an army of part-time media buffs to watch and tag content with generic information, the primary data that shape its increasingly-personalized recommendation system. Netflix maintains relatively distinct workplaces, too, between its engineering corps and data scientists based in Northern California and its talent and content acquisition team in the production centers of Southern California. As Chief Product Officer Neil Hunt notes of this division of labor, “The contract between us, roughly, is whatever they buy we figure out how to get the most value out of it by putting the right stuff in front of the right people.”

Ultimately, and not unlike a traditional network head, final say for original programming falls to Chief Content Officer Ted Sarandos, whom profiles portray again and again as a sort of television Billy Beane, the baseball executive known for popularizing the use of advanced metrics in the sport and the subject of 2011’s Moneyball. Sarandos’ daily dilemma, to paraphrase Todd Gitlin, might be called “the problem of knowing too much”: finding useful needles of data among haystacks of distractions AND determining how to use those data to marshal resources for content (and organization of that content) that speaks to loyal viewers.

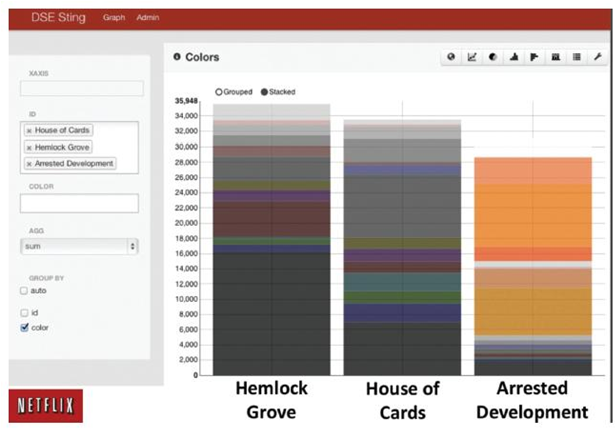

Although the network is notoriously tight-lipped about how and to what ends it deploys data analysis, small indications exist that, in the aggregate, provide a clearer picture about the decision-making process behind Netflix originals like BoJack Horseman. For instance, in interviews creator Raphael Bob-Waksberg highlights Netflix’s eagerness to offer notes on the minutest of creative choices like background music, as well as its amenability to serialized storytelling and binge watching, something he saw as crucial to the show’s comedic sensibility. One can infer, then, that Netflix provided Bob-Waksberg with data supporting these creative choices without forcing them, as accounts of “Netflix-as-culture-machine” would have us believe. For other original shows, Netflix has revealed the importance of title cards to a viewer’s browsing experience and how data about color patterns drive viewers of, say, a PBS prestige drama to a Netflix original like House of Cards.

So what do Netflix’s programming decisions say about its desired or presumed viewership? For most of its short history, Netflix’s original shows have functioned a lot like HBO’s in the 2000s–programs that need to generate buzz and drive subscriptions, not necessarily shows that will make up their production cost. Until recently, this has meant dark or sensational dramas like House of Cards and Orange is the New Black. But the network’s increased forays into original comedies offers further fodder for understanding how Netflix targets certain viewing groups as it continues to grow. At the end of 2013, Netflix hired a new executive to oversee comedy development, Jane Wiseman, whose credits include niche-but-buzzy network fare like New Girl, Community, and Parks & Recreation. Her pedigree and shepherding of BoJack Horseman highlight two key aspects of Netflix’s comedy strategy. First, to develop comedies that resonate with the aesthetic and binge-ability of the prestige dramas–like those mentioned above, as well as Mad Men and Breaking Bad–already owned or licensed by Netflix. Second, to develop content translatable to the international market in order to avoid the time and cost of region-specific licensing as Netflix expands globally, aiming to be in 200 countries by 2016.

To that end, Netflix has signed comedian Adam Sandler to a four-picture deal, one described by Sarandos as “data trumping conventional wisdom” because of Netflix research indicating Sandler performs much better on home video and in foreign markets than at the American box office. The network’s forthcoming day-and-date release of the Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon sequel also represents a clear attempt to establish a foothold in the lucrative Chinese market, but in a way familiar to Western fans of the original film. With this two-pronged approach, then, Netflix is re-interpreting an industrial blueprint in place since the dawn of the FOX network and merger mania of the late 1980s. But what difference, if any, exists in the resulting original programming, and what does this mean about the nature of creativity in the “Data Era?”

Part Two explores this question by looking closely at the Netflix original comedy BoJack Horseman.

Image Credits:

1. Netflix

2. Netflix Color Chart

Great article. thanks