Expanded Cinematography, or the Problems Workflow Won’t Solve

Christopher Lucas, Trinity University

In 2013, two articles came to my attention that raised difficult questions about the future of cinematography. One was a critical look at the state of gender equity in the trade. The other was by the founder of a forward-looking education project attempting to reclaim a share of authorship that has seeped away from cinematographers with the rise of digital filmmaking techniques. The art and craft of cinematography is changing, and certainly new technologies fo dissertation writer and specializations will be part of the new definition of the craft, but I want to suggest here that the idea of an expansive, open cinematography may rely less on the number of new workflows it learns, and more on the openness of its practitioners, and those that hire them, to new types of artistic voices.

Precisely what cinematography means in this day and age has become a pressing question for the craft (and, hopefully, some educators). Yes, skilled cinematographers continue to be hired for projects large and small, although, as I wrote in my last Flow submission, pay scales have become severely depressed in the growing online and non-union sectors of the industry. And, of course, Academy Awards are still awarded to the high-end practitioners in this branch of the “art and science” of motion pictures, helping extend our image of cinematography as a coherent professional locus. Increasingly, though, there is widespread confusion over how the visual design of films is conceived and executed and who is responsible for that work. For example, between 2011 and 2014 the academy awards for cinematography and visual effects were awarded to the same films: Avatar, Inception, Hugo, and Life of Pi. The 2015 Oscars may be an exception that proves a new rule as Birdman’s Emmanuel Lubezki won for Cinematography (for a film with many visual effects elements) and Interstellar won for Visual Effects (for elegant if rather familiarly-defined “outer space” visual effects).

In 2012, two established and respected cinematographers, Vilmos Zsigmond, ASC, and Yuri Neyman, ASC, founded the Global Cinematography Institute, a training program in Los Angeles built around a concept they call “expanded cinematography”—arguing that cinematographers must find a way to expand their craft influence into the pre-visualization, visual effects, and post-production stages of film production. GCI promised to do that with courses and workshops from experts from those neighboring specializations. As Neyman wrote in a series of articles and op eds accompanying the group’s launch, GCI has recognized that the “pre- through post-“ workflow of classical film production is increasingly a weak construct for understanding how creative decision-making actually happens in film production. The new by-word is non-linear/real-time: workflows in which decisions about look, contrast, color, tone, and grain (or any number of aesthetic qualities usually associated with cinematography), as well as editing, visual effects, and other craft work may be taken at any point in the production process. GCI’s stated goal is to create a new model of cinematographer, better able to assert “image control” and cinematographers’ intentions in this new work process.

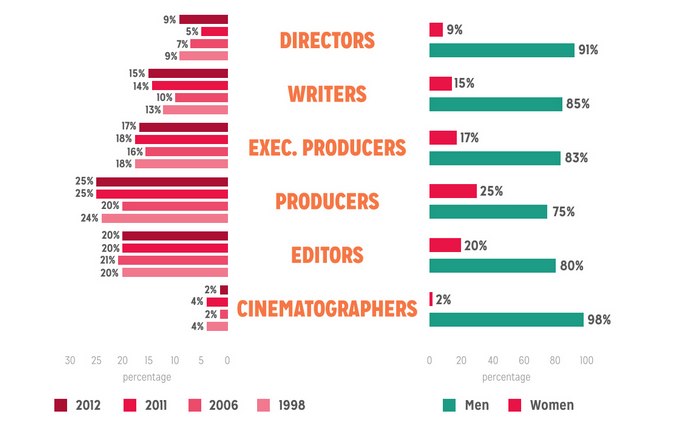

Alongside this narrative of technological obsolescence, cinematography has periodically grappled with the lack of gender equity in its professional ranks. In 2013, The New York Film Academy issued a report that raised this question yet again. To the surprise of many, the report showed the industry making almost no headway, with women photographing only 2-4% of the Top 250 films over the last five years. This, despite broad discussion of the issue, increased enrollments of women in film schools, films like Women Behind the Camera and efforts by some cinematographers to advocate for more diverse crews. In the wake of this sobering report, lists emerged highlighting talented women DPs (often recycling the same small pool of names), and yet more think-pieces dwelling on the sources of this disparity.

These crises within cinematography may seem unrelated or only loosely joined, but its notable that both are rooted in a very traditional notion of the division of labor in film production. Ultimately, in each, the concept of cinematography circles around the notion of the “on set” cinematographer. Not without reason, since the idea of director of photography as head of the camera department retains significant currency in labor force organization to write my essay, and within the union definitions that guide hiring and compensation. In this traditional conception, the on set cinematographer is the primary interpreter of story in visual terms—the “visual storyteller”—second only to the director in the realization of the look of the film. To include women in this vital role, prescriptions of groups like IATSE typically involve bringing more women into entry level camera crew positions or focusing on making camera crews more welcoming to women (sexism on set remains a pervasive problem). Even the “expanded cinematography” of GCI envisions the cinematographer as needing to reach out, seeking invitations from beyond his or her base on the film set to influence other parts in the production process.

All of these discussions may miss an important point in the emerging film production process. Simply put, in more and more cases the job of a film crew is to realize shots (or even just elements of shots) planned, designed, and conceived by others in the filmmaking process. Such work requires a lot of skill and collaborative sensibility, of course, but it also cuts against the discursive construction of the cinematographer as artist/technician contributing their singular vision to the film. Arguably, Sharon Calahan is one of the most influential cinematographers (man or woman) of the last 15 years. As first a “lighting designer” on Toy Story (2005), then Director of Photography on later Pixar projects, she has translated the language of cinematography into the created at https://grademiners.com/research-paper worlds of animation. In 2014, Calahan was invited to join the ASC—the first cinematographer the group invited a member whose entire body of work was digitally created. I find this both remarkable and entirely predictable in that, as Calahan has noted, her work represents the most visible edge of hundreds of animators and coders tasked with creating visual looks in the virtual animated worlds of Pixar’s films. In other words, it’s a definition of the cinematographer that fits quite nicely with ASC’s efforts to define the work of its members as primarily “conceptual.” Given the prominence of next generation DPs like Calahan, it’s not surprising that some respected traditional cinematographers have also moved into animation in a “consultative” role, as with Roger Deakins’ work on Wall-E (2008), How to Train Your Dragon (2010), and Rango (2011).

So, what kind of “expanded cinematography” do we want at the end of the day? For both the digital crisis and the equity crisis, “solving” the problems is placed almost entirely at the feet of cinematographers. In keeping with craft’s long-standing investment in individual virtuosity, the (by-now familiar) refrain is: innovate or die. In practice, though, producers and director are responsible for hiring cinematographers, and have enormous influence (through budget and stylistic goal-setting) on the workflows built around specific film projects. In other words, although cinematography absorbs a great deal of blame for its resistance to digital cinema, as well as residual misogyny and slow acceptance of women in the workforce, a large part of the essential conservatism of the craft comes from these hiring practices in which older, established cinematographers, laden with awards or thick CVs, always get the first call from risk-averse producers and directors.

The old school of cinematography can do its best to train itself in these new specializations, although the industry has already created and staffed those roles and it unlikely to “un-crowd” the workflow with technicians. Battles over creative authority will be eternal, and next generation cinematographers will push back on pre-viz artists, colorists, and the VFX department to make its contribution known. But the recent trend is toward more centralization of that authority under directors and producers, now enabled to bring visual design decisions further “above the line” than they have since the earliest days of the art form. Meanwhile, craft areas will fight over smaller crumbs of creative input, and more hyphenates (director-cinematographers, etc.) will emerge reflecting that centralization. Cinematographers can continue to circle the wagons around their traditional notion of the journeyman-craftsperson on-set, a blue-collar, classed and gendered concept of the work, or it can embrace its more creative legacy, the pluralism of artistic endeavor. It can open the doors to a wider variety of artists. It’s time for cinematography—and the producers and directors that support it as an art form—to consider a truly expanded cinematography, a more intersectional cinematography, that welcomes more women, people of color, and greater diversity of sexualities.

Image Credits:

1. Bradford Young, cinematographer for A Most Violent Year.

2. A new training program founded by Vilmos Zsigmond, ASC, and Yuri Neyman, ASC promises to expand the definition of cinematography.

3. A study by the New York Film Academy showed little progress for gender equality if key roles in film production.

4. Pixar “Lighting Director of Photography” Sharon Calahan was admitted to the ASC in 2014, the first member whose entire body of work was computer generated.

Please feel free to comment.

We help writ http://writingby1click.com/