Beyond Privacy: Concerns about social surveillance Jacqueline Ryan Vickery / University of North Texas

Each semester I teach courses on digital media, which means each semester I discuss issues of online privacy with college students. While their concerns and practices have evolved over the course of these conversations, one privacy issue keeps emerging as increasingly concerning to them: (future) employers’ use of the internet to find information about them. While the internet can be a great tool for networking and promoting one’s work etc., it can also lead to unwanted discoveries and misinterpretations. It seems almost every week I read yet another news story about someone being fired for something they said online. To a certain extent, some of these firings seem justified, as might be the case if an employee discusses something that explicitly violates company policies of disclosure or conduct. However, in far too many instances, the firings bring up questions of ethics, privacy, identity expression, and work-life boundaries that make me, and my students, increasingly uncomfortable.

Take for example, the Ohio elementary school teacher who posted pictures of live animals in crates on his Facebook account. He is a vegan and was trying to raise awareness about the inhumane treatment of many farm animals. This is quite clearly a personal value that does not disgrace the school, nor present him as an unacceptable role model for students. Yet, he was fired for expressing his vegan values. The reason? His school was in a rural area of Ohio, one in which many of his students’ families earned their income from farming. He was told he, “might offend the community and the economic interests of the community…if [he] wanted to be a strong vegan advocate, [he] might want to look into something other than teaching.” Nevermind that he was offended by the unethical treatment of animals, his potential to offend others (and threaten their economic interests) was deemed more important that his right to express himself online. To me, the school infringed upon the teacher’s right to his own beliefs and the right to freely express those beliefs in a personal space. What this example highlights (and it is only one of many, many, more like it) is that the ways in which employers are surveilling employees’ online profiles is just as much about identity and speech as It is privacy. Really, it’s about constructing particular subjectivities that are valued in the workforce, even at the cost of other subject positions and identities.

Far too often, conversations about employers’ use of digital media to monitor employees get thrown into the camp of “well, just be careful about what you put online.” In other words, don’t be stupid about what you share with your employer and you’ll be fine. Similar to my earlier Flow column regarding sexting and Snapchat, I believe this rhetoric falsely presumes that we are the only ones responsible for our own privacy and that we have complete control over privacy. It reduces a complicated issue – identity expression and speech – to an issue of mere individual responsibility, and thus dismisses the questions of ethics and boundaries all together. What the Ohio teacher example reveals is the extent to which we are being disciplined to think of our online identities – and therefore our subjectivities – first and foremost in terms of workers. Arguably the Ohio teacher did not do anything patently offensive, did not bring shame or harm upon the school or his students, and in all likelihood thought he was “being smart” about what he posted. Yet, in essence what the school fired him for was for expressing beliefs that were in contrast to those of his work environment. That’s it. And that’s scary.

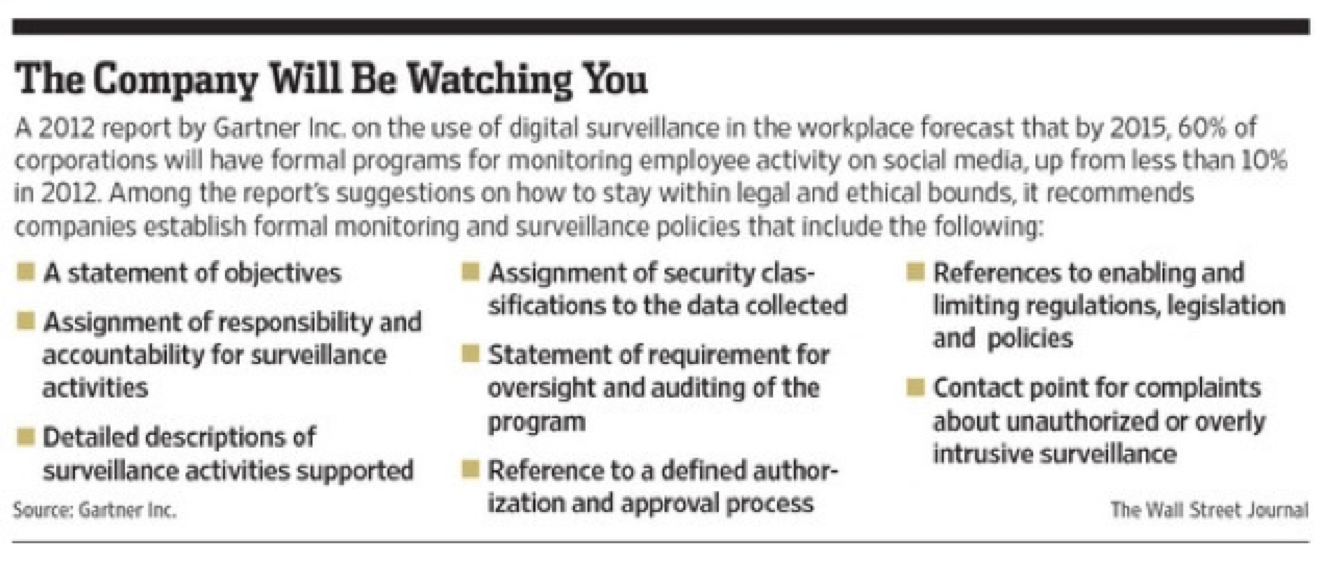

Computers and internet-enabled technologies have been constructed as “boundary-crossing” technologies1 that permeate and blur the boundaries of personal and work life. Such technologies have led to a variety of legal issues, such as, when can an employer view files on a company-owned laptop that the employee also takes home? Can an employer access text messages sent outside of work hours if the employee’s mobile service is paid for by the employer? Can employees have any expectations of privacy when accessing personal email at work? Such issues have been addressed in court to varying degrees. At the heart of the issues is the fact that telecommunication technologies allow for our personal lives to be increasingly visible and accessible at work, and of course that means it is increasingly possible for work to invade our personal spaces and time as well (e.g. how many of us check work email from home and “off the clock” on a daily basis?).

Thus, the use of social media becomes just the latest iteration of slippery legal and ethical questions we must consider, questions that require us to re-think boundaries between personal and work life. Certainly a lot of employees create and maintain accounts on social media prior to being hired, they use them to connect with individuals outside of work, and often think of them as personal and private spaces. Even though employees may know their employers may have some access to the accounts, that doesn’t negate the fact that we still tend to think of our social media profiles as personal spaces for expression and connections. Research demonstrates that social networking sites are useful in helping us maintain latent and weak ties, and to acquire emotional and social capital.2 There are a lot of uses, motivations, and benefits of participating in social media that have little to nothing to do with our roles as workers in the marketplace.

Likewise, the internet has been heralded as a tool for democracy that allows underrepresented or misrepresented populations to express their opinions and experiences.3 While we know that there are limitations and deep-seeded systematic inequalities that cannot be easily eradicated via the internet, it does nonetheless provide spaces for marginalized populations to potentially network, build community, organize, and foster change.4 However, such opportunities are likely to be stifled when we are disciplined to first and foremost think of ourselves in terms of (potential) employees. Within a neoliberal context, we are being disciplined to use online spaces as sites to invest in our “human capital”.5 Thus, I think it is imperative we ask: what are we sacrificing and what is the cost (to ourselves and to society) when we must not only police what we share and say in online spaces out of fear of being fired for personal activities, but when we must also think about how our personal values could potentially hurt our reputation in the workforce (even when they do not intersect with our job descriptions)?

Furthermore, the extent to which individuals must invest in their “good worker” identities (i.e. ability to capitalize on their skills, qualifications, qualities, etc.) becomes even more problematic when we take into consideration the literacies and skillsets necessary to intentionally construct positive online identities (as are interpreted by the marketplace). Research reveals that some individuals are better prepared and equipped to participate in such ways, as compared to others. Knowingly constructing an “acceptable” online identity involves not only technical access and competencies, but also an understanding of social and network literacies that some individuals have not developed,6 nor do employees and employers necessarily share the same culturally contextualized understandings of these spaces and identities.

To return to the concerns expressed by the college students in my classroom, here’s what I’m seeing – to a certain degree they are hyper aware of online privacy concerns; they know not to post pictures of red Solo cups, they know that even a cigarette might be mistaken for a joint, they know better than to be blatantly racist or homophobic. In other words, they’re trying to do all the “right” things online so they can get jobs. But what I’m hearing is that they are so afraid of something being taken out of context – an offhand joke between friends – or that their sexual or religious or political identities might be used against them, that some are opting out of online social networking almost all together. There’s a reason they are using private Instagram accounts, ephemeral Snapcaht apps, and anonymous Tumblrs – these sites are disconnected from any sort of public online profile or community. On the one hand, these are effective strategies that afford greater privacy and therefore more freedom of expression. But, we also know that social networking sites such as Facebook and Twitter are good at maintaining weak ties with those who aren’t in our immediate social circles.7 Weak ties are valuable for exposure to diverse ideas, for getting jobs, and expanding opportunities. When students opt out of the more diverse and open “networked publics” for the more insular and private forms of interpersonal communication, what is lost?

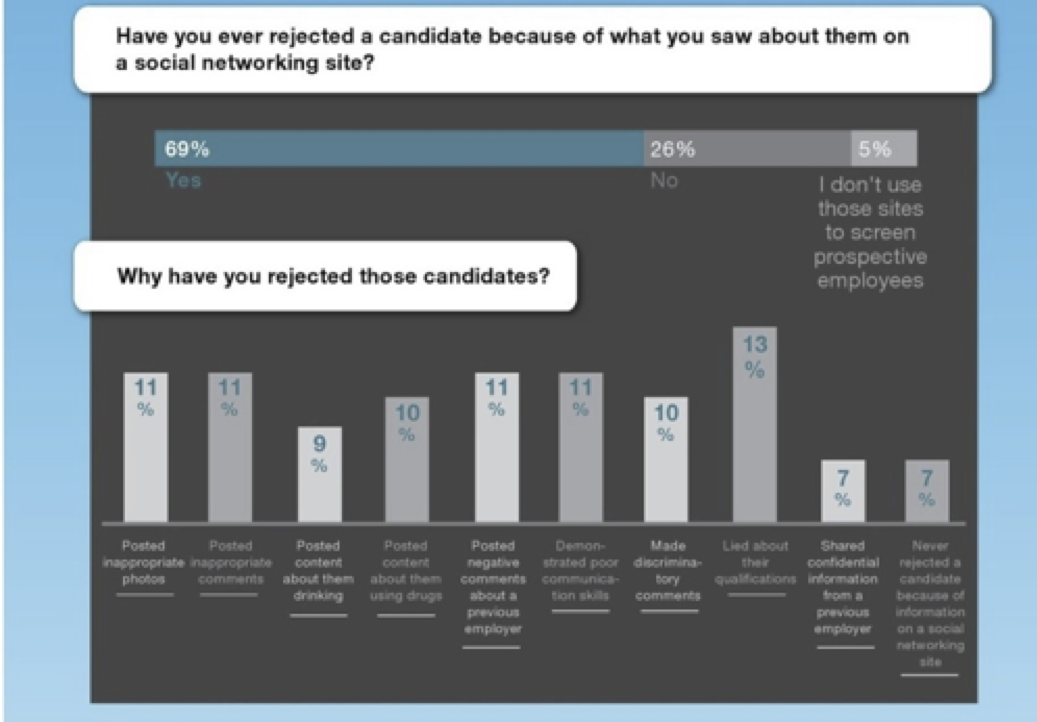

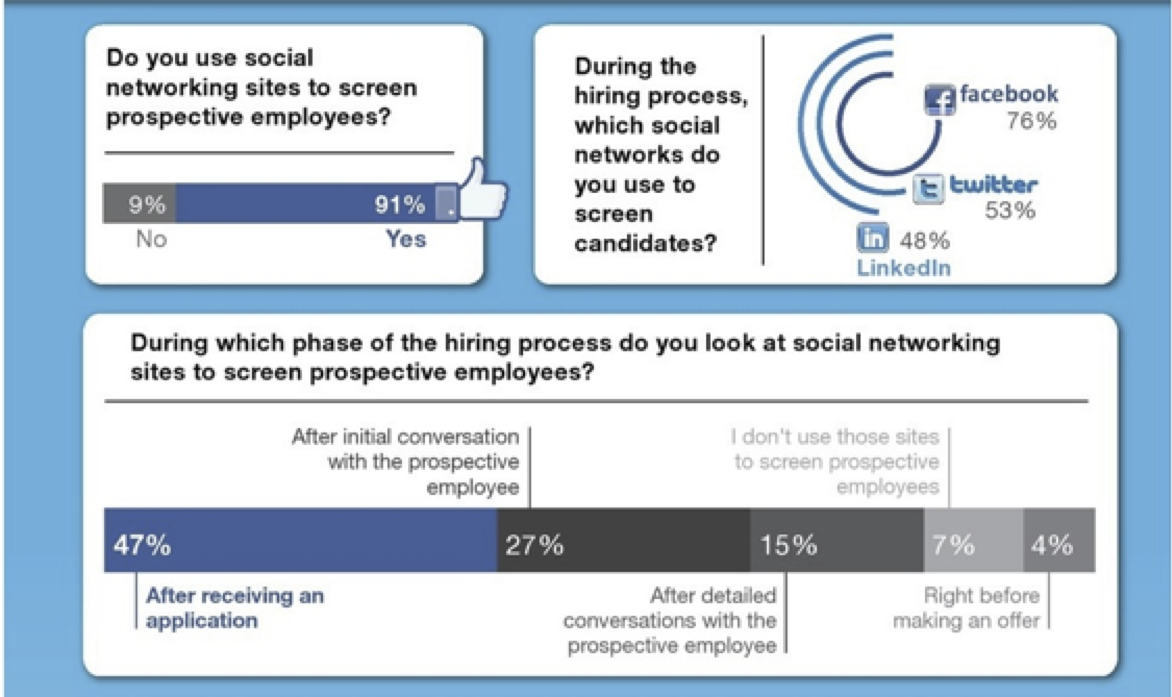

Lastly, I’ve been primarily discussing this in the context of middle-class jobs and middle class employees. But how do these issues become even more important when we think about minimum wage jobs and nondominant populations? Low-income workers are often subjected to greater surveillance,8 for example, as evidenced by drug testing for minimum wage jobs (but not white-collar jobs). Additionally, many nondominant populations may not have the digital and social literacies required to protect their privacy and construct “good” online identities. We should be concerned that employee surveillance further exasperates inequalities. Who is being monitored, in what ways, for what purposes? How much transparency is there? To what extent should employers at the very least inform employees that they are being searched and monitored? What about individuals who opt out of online networks all together? Or those who have really common names that can lead to mistaken identities or guilt by algorithmic association? Or those who have adolescent mistakes in their past they would like to cover up and move on from? Or what about nondominant expressions of cultural capital that are ripe for misinterpretation from those who benefit from and maintain the status quo?9 And, of course we can’t overlook the opportunities for blatant discrimination based on age, sex, ethnicity, and religion. While these are legally protected categories, we know that in practice it is all too easy for an employer to ascertain this information online. And we cannot forget that there are still 29 states in the U.S. in which it is legal to fire someone for being gay (an identity no one should have to hide, and yet social media often renders visible and thus open to discrimination).

These are all legitimate privacy concerns, and thankfully some are starting to be addressed in legal literature.10 But what I’m also increasingly concerned about are the unintended consequences that extend beyond explicit questions of privacy in and of itself. I worry that these modes of surveillance have the potential to chill speech, further silence marginalized identities and experiences, and hinder opportunities for individuals to invest in and acquire other kinds of capital (such as social, emotional, and political). The effects of employee monitoring serve to discipline individuals into modes of self-regulation that have potentially detrimental effects and consequences that far exceed blatant discriminatory hiring/firing practices. Thus, we need to think deeply and critically about how privacy laws and norms must evolve to take into consideration not only expectations of privacy, but also the detrimental consequences surveillance has on other areas of online and offline life and society. And lastly, we need to know who is most likely to be harmed by these practices. My concern is that not all populations are equally affected by increasing modes of online surveillance, thus as researchers we must continue to conduct in-depth, empirical, critical, and diverse research into such questions.

*Author’s note: This article is very much a work-in-progress as I am beginning a much larger empirical study into these questions. I would greatly appreciate any advice and feedback about the direction the research should take.

- Abril, P.S., Levin, A., and Del Riego, A. (2012). Blurred boundaries: social media privacy and the twenty-first-century employee. American Business Law Journal, 49(1), pp. 63-124. [↩]

- Ellison, N.B., Steinfield, C., and Lampe, C. (2007). The benefits of Facebook ‘friends’: social capital and college students’ use of online social network sites. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 12(4), pp. 1143-1168. [↩]

- See Rheingold, H. (2002). Smart Mobs. Cambridge, MA: Basic Books; Shirky, C. (2008). Here Comes Everybody. New York: Penguin Press. [↩]

- See Jenkins, Henry. (2006). Confronting the Challenges of Participatory Culture. Digital Media & Learning. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.; McChesney, R. (2012). Digital Disconnect: How Capitalism turned the Internet against Democracy. New York: The New Press. [↩]

- Foucault, M. (2008). The Birth of Biopolitics: Lectures at the College de France, 1978-1979. New York: Palgrave MacMillan. [↩]

- See Arthur, J. and Davinson, J. (2000). Social Literacy and Citizenship Education in the School Curriculum. The Curriculum Journal, Vol. 11, No. 1, pp. 9-23.; Miles, A. (2007). Network Literacy: The New Path to Knowledge. Screen Education Autumn.45, pp. 24-30. [↩]

- Steinfield, C., Ellison, N.B., and Lampe, C. (2008). Social capital, self-esteem, and use of online social network sites: a longitudinal analysis. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 29(6), pp. 434-445. [↩]

- Gilliom, J. (2001). Overseers of the Poor. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. [↩]

- See Carter, Prudence. (2007). Keepin’ It Real: School Success Beyond Black and White. New York: Oxford University Press. [↩]

- See Abril, P.S., Levin, A., and Del Riego, A. (2012). Blurred boundaries: social media privacy and the twenty-first-century employee. American Business Law Journal, 49(1), pp. 63-124.; Kane, B. (2010). Balancing anonymity, popularity and micro-celebrity: the crossroads of social networking & privacy. 20 Alb. L.J. Sci. & Tech. 327. ; Strutin, K. (2011). Social media and the vanishing points of ethical and Constitutional boundaries. Pace Law Review, 31(1), article 6. [↩]

So this was so useful for me.