“SNL 40” and the Death of Liveness

Nick Marx / Colorado State University

Liveness has long been popularly thought to be at the core of television’s essence as both an information and aesthetic medium1. Today, though, what’s left of the collectively-experienced, evanescent moments made possible by live broadcasting provide the only incentive for audiences to tune-in at appointed times and schlep through commercial breaks. Over a decade in to television’s on-demand-driven era of convergence, we’ve grown alternately to embrace and tolerate liveness mostly for major sports match-ups and special events like awards ceremonies. This trend only seems likely to continue with every new record-breaking telecast rights deal between networks and sports leagues or record ad rate for an Oscar broadcast. At the same time, and with considerably less hullabaloo, the pleasures and possibilities of liveness have inexorably ebbed from just about every other form of scripted television entertainment. This has been particularly apparent in the last two seasons of Saturday Night Live, coming to a head earlier this month with the sketch comedy stalwart’s 40th anniversary special, “SNL 40.”

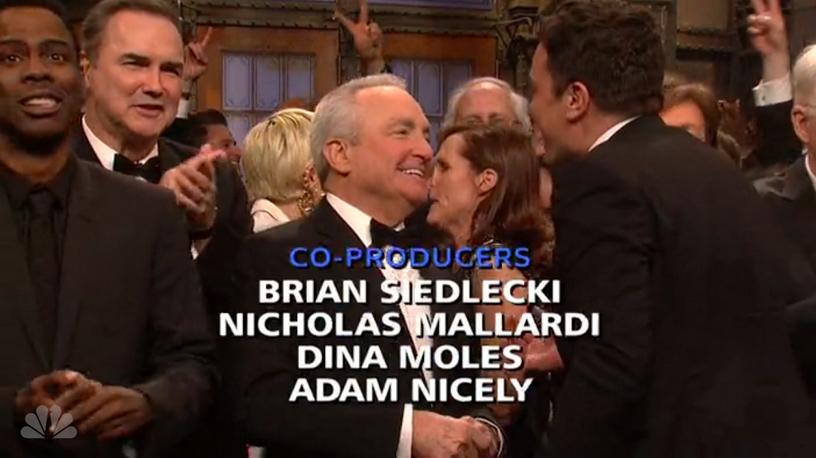

As it’s always been with SNL, the small, fleeting moments tend to be the show’s most significant ones. To the chagrin of many SNL devotees, Eddie Murphy’s appearance on “SNL 40” was stilted and brief, awkwardly cutting to commercial when it became clear Murphy would give little more than a perfunctory “thanks.” Noted small person and longtime Lorne Michaels confidant Paul Simon closed the show with “Still Crazy After All These Years,” a gentle performance no less touching than the first time he sang it on SNL’s second episode in 1975. Maybe the most meaningful small moment of the special, though, arrived at the end as several generations of SNL cast-members and celebrities crowded the studio 8H stage to wave goodnight. Michaels grudgingly received their well wishes as the credits rolled, but not before The Tonight Show host Jimmy Fallon quickly darted over and shared a private sentiment that elicited a rare, publicly visible smile and laugh from Michaels.

Fallon had opened the show performing a medley of SNL highlights alongside Justin Timberlake in exactly the kind of quick-hit mash-up that’s ready made for Internet spreadability. Of course, excerptible digital videos have become The Tonight Show’s calling card under Fallon and Michaels, extending the show’s cultural reach beyond late night in much the same way The Lonely Island’s digital shorts did for SNL a decade ago. Eddie Murphy’s “SNL 40” appearance has similarly lived on in social media conversations not because of what he did or said onstage, but because of the stories popping up in its wake. According to former cast-member Norm Macdonald, Murphy declined the opportunity to lampoon Bill Cosby’s many sexual assault allegations in a “Jeopardy!” sketch, a decision for which Cosby then publicly thanked Murphy.

As Mike Myers and Dana Carvey unintentionally noted in a “Top Ten” list during their “Wayne’s World” sketch, liveness has become the least important aspect of Saturday Night Live, particularly as a site of aesthetic innovation. Splitsider’s Erik Voss made a similar observation in breaking down last season’s brilliant “Darrell’s House” sketches, in which a public access television host played by Zach Galifianakis frustratedly asks for several of his flubs to be fixed in post, with the version containing his requested cuts airing half an hour later in SNL’s live broadcast. According to Voss, the sketch demonstrates an experimental sensibility—one fundamentally based in liveness—rarely seen in SNL’s predictable parade of pre-“Weekend Update” parodies of celebrities and political goings-on.

SNL’s move away from liveness is partly a matter of survival. The show is in year two of a very rough rebuilding process, and it has increasingly relied on recorded material—comprising a full third of the show now—and writers trained at the Internet comedy powerhouses of Funny or Die and CollegeHumor to ease the transition. The diminished role of liveness on SNL is also a matter of generational tastes. The baby boomers of SNL’s early cast and writers were weaned on the vaudevillian holdovers and boozy breaking of live, network era, variety-style comedy. The current cast, all of whom were born after SNL’s 1975 premiere, are more literate in the millennial sensibilities of mash-up and distracted viewing.

More than anything, though, SNL is participating in a broader debunking of liveness as television’s ontological essence. Certainly, live events continue to be incredibly important to television networks and advertisers. Their cultural import, however, is highly dependent on their afterlife among social media networks and news cycles, or at least upon the success or failure of the next hastily-produced awards show to generate clicks. Some live events seem to be cynically conceived of as a Twitter trending topic first and as a television entertainment program in name only. With an increasing investment in collapsing the distinction between the two, SNL might just as well have displayed a graphic for “Liveness” during the “In Memoriam” segment of “SNL 40.”

Image Credits:

All images are from the author’s personal collection.

Please feel free to comment!

- Of course, the notion of liveness as television’s ontological essence has been thoroughly critiqued by television scholars over the years. See, among others, Jane Feuer, “The Concept of Live Television: Ontology as Ideology,” in Regarding Television: Critical Approaches—An Anthology, ed. E. Ann Kaplan (Los Angeles: The American Film Institute, 1983) and Elana Levine, “Live! Defining Television Quality at the Turn of the 21st Century,” http://cmsw.mit.edu/mit3/papers/elana_levine.pdf [↩]

So we know about the game.