Consumption, Class, and Gender in the Made-For-TV Holiday Movie

Kathleen Battles / Oakland University

They start before Thanksgiving and continue through New Years. On the Hallmark Channel, Lifetime TV, and ABC Family, they dominate the schedules. They are the Thanksgiving and Christmas made-for-TV movies. Low budget, formulaic, and primarily geared to themes of romance and family, they are made for women audiences who are packaged and sold as a prime audience for big box stores like Walmart. There are many things that one could say about these movies, but for this piece, I’d like to comment on the contradictory class dynamics of two of these holiday films as inflected by gender, sexuality, and race. The first is the 2011 Lifetime TV film, Dear Santa, starring Buffyverse star, Amy Acker and directed by original Beverly Hills 90210 star, Jason Priestly. The second is the 2013 ABC Family movie, Holidaze, starring original Beverly Hills 90210 and later WB series star, Jenny Garth, and former ABC soap star, Dancing with the Stars contestant, and current Good Morning America contributor, Cameron Mathison (synergy!). These films come at their class politics in different directions, but together tell us something about the relationship between gender and consumption in the neo liberal era.

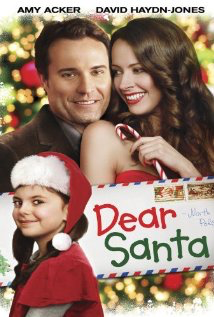

In Dear Santa, Amy Acker plays Crystal, a 30-year-old heiress who spends her days shopping and hanging out with her friends. An ultimatum from her parents that she find some direction for her life or face losing her credit cards leads Crystal on a search for purpose. She finds it in a letter to Santa that “fatefully” blows into her path on a gusty day. The letter was written by a young girl, Olivia, whose Christmas wish is that her widowed father, Derek, find a new wife, and she a new mother. Crystal decides that purpose could be found in helping the family, and proceeds to follow father and daughter around for a day, until she follows Derek into a building, which she turns out to be a soup kitchen. At first, Crystal is befuddled, but her sparkly “can-do” spirit quickly wins the admiration and affection of Derek, Olivia, the gay chef (signaled by his flamboyant hot pink uniform), and the homeless patrons of the kitchen. The movie then proceeds through typical romantic comedy obstacles, the most significant being Derek’s girlfriend, a predatory career woman whose values do not align with his. Over the course of the film, Crystal’s inherent goodness comes to the fore, and she begins to use her money to help the shelter instead of herself, and, as predicted finds love and comfort in a modest, family based life that she could never seem to find as a rich girl.

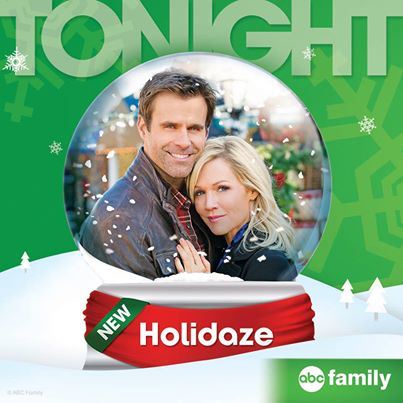

Holidaze is one of a number of holiday films focused on the empty lives of career driven women, and is also much heavier on plot twists than Dear Santa. Melody “Mel” (Jennie Garth) starts out as a high-powered, multi-lingual executive for a large, Walmart style corporation, Save Now. Save Now is planning on opening a store in the small town of Streetsville, Mel’s hometown. Her boss promises her a coveted promotion to international development if she can help finalize the deal with the town. Though less than half an hour from Chicago, Streetsville is more quaint small town than suburb, and its residents, including Mel’s former fiancé, Carter, do not want the big box store, which they fear would cripple the robust small business community, which includes Mel’s mother as well as Carter. In a classic case of head injury induced amnesia, Mel’s dreams that she stayed in Streetsville, married Carter, and opened both a local café and a small inn. Upon awaking, after a second fantasy head injury, Mel decides to commit herself to both Carter and the small town she spent her adult life running away from. Happiness comes when she gains Carter’s renewed love by spearheading the successful attempt to stop the Save Now from opening in Streetsville.

What is striking about these movies is that happiness for both Crystal and Melody is found through downward social mobility, a kind of reverse Cinderella story. While both women are urban and urbane in their tastes and preferences, they both fall for flannel shirt wearing, working class men; Derek runs a snow plow business; Carter a furniture building business. Both films build a stark contrast between the sterile coldness of urban consumption based lifestyles and the more homespun values of working class or small town life. Both Crystal and Melody live in high rise type buildings devoid of “hominess,” while Derek and Carter live in a simple wood frame house and quaint historic inn, respectively. The more complicated Holidaze offers and even more complex set of binaries between the small town, small business, “Main Street” values of Streetsville merchants and the giant, global, impersonal, exploitative, profit above all values of Save Now. Redemption and happiness for both heroines is found in leaving behind the trappings of shallow self centered consumption or careerism, in favor of a “simpler” life of “traditional” values.

But, these films are also made specifically as placeholders for the onslaught of consumer advertising key to the economic success of the holiday season. In other words, these films cannot completely reject consumption; in fact, consumption becomes key to each character’s development. The connection between gender and consumption in the neoliberal era is one that has been explored by a number of media scholars. A number agree that the current moment has ushered in a postfeminist moment in which feminist goals of independence and equality for women as a group have devolved into a vision of female self empowerment enabled through individual lifestyle choices fueled by consumption and brand logics. From Sarah Banet-Weiser’s discussion of the “can-do” girl, Yvonne Tasker’s analysis of Enchanted, to Rosalind Gill’s discussion of shifting ideas of romance in postfeminist media culture, we see that media targeted at women offers us plucky, independent, spirited heroines who nonetheless long for a return to pre “feminist” modes of femininity; i.e. a traditional life.123

Frivolous consumption and single-minded careerism are not good qualities for white women in these films. But, fortunately, these qualities can be recuperated. Poor little rich girl, Crystal, might have once been aimless, but her lifetime of training in childlike frivolity is precisely what infuses joy back into the hearts of Derek, Olivia, and even the homeless patrons of the soup kitchen. While the shopping montage scene is a key transformative moment towards upward class mobility in films like Pretty Women and Enchanted, in Dear Santa, Crystal empties out her closet of designer outerwear to bestow upon the homeless in a moment of selfless transformation. The key shopping montage is when Crystal takes Olivia out shopping after learning she is being teased in school for her unhip, Dad purchased wardrobe. A dying party is brought back to life by the urbane Crystal and her gay BFF through an infusion of dance music, homemade eggnog, and canapés. In Holidaze, Melody ends up gaining the trust and love of Carter by saving Streetsville and his inn from the imposing Save Now by appealing to a higher level executive who assures the residents that the corporation would never intrude where it was not wanted. While a great deal of the film is spent elevating the values of small businesses over and against multinational conglomerates, by the end we find rapprochement when the executive agrees to Melody’s plan to franchise a line of homey cafes in Save Now stores, complete with local produce and products. Mel can have love, a small business, and even a franchise, as long as she gives up her more cosmopolitan, career-driven lifestyle.

Steeped in romance, and chock full of those conservative, heteropatriarchal values that made Eve Sedgwick refer to the Christmas season as that time when our social institutions speak in one voice, holiday made-for-TV movies consistently emphasize heterosexual coupling and traditional family life as the key to happiness for women.4 But in the postfeminist era of multinational capital and the social imperative of lifestyle-based consumption as the key to identity building, these movies cannot be too traditional. While stories of upward class mobility continue to abound (there are plenty of holiday movies about regular women ending up with princes!), these tales of downward mobility work to close the gap between a nostalgic longing for “tradition” and the compulsory gendered requirement of full participation in consumption based lifestyles.

Image Credits:

1. ABC Family’s 25 Days of Christmas

2. Hallmark’s Countdown to Christmas

3. Lifetime’s Dear Santa

4. ABC Family’s Holidaze

5. Jennie Garth as Mel in Holidaze

Please feel free to comment.

- Banet-Weiser, S. (2012). Authentic™: The politics of ambivalence in a brand culture. NYC, NY: NYU Press. http://nyupress.org/books/9780814787137/ [↩]

- Tasker, Y. (2011). Enchanted by postfeminism: Gender, irony, and the new romantic comedy. In H. Radner & R. Stringer (Eds.), Feminism at the Movies: Understanding gender in contemporary popular cinema. London: Routledge. http://www.routledge.com/books/details/9780415895880/ [↩]

- Gill, R. (2007). Gender and the media. London: Polity. http://www.polity.co.uk/book.asp?ref=9780745619156 [↩]

- Sedgwick, E. (1993). Tendencies. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. http://books.google.com/books/about/Tendencies.html?id=t38DOGvPZiIC [↩]

I liked how Jennie Grath’s character Mel is handled in the movie. I liked Holidaze more than Dear Santa.