Marathon Viewing E.R.: Rewatching Television’s Greatest Prime-Time Serial

R. Colin Tait / Texas Christian University

Rewatching the series also makes one wonder, how did E.R. fall through the cracks? How could network TVs most talked about, most expensive, most dramatic, longest-running medical series have so little writing devoted to it? It was nominated for 124 Emmy Awards, and won 23 with prizes in every category it was nominated in. It was also the highest-rated drama series for years running and according to former NBC president Warren Littlefield made the network over three billion dollars and for ten of its fifteen seasons it was a “top ten rated show”1. Despite the fact that it was financed by the network at a deficit, with costs eventually as high as $13 million per episode, the series never lost money.

Its highest-rated episode, “Hell and High Water,” where George Clooney’s pediatrician Doug Ross saves a child from a storm drain garnered 48 million viewers — a benchmark for a dramatic series not likely to be broken in our currently fragmented cable universe and ushering Clooney’s movie stardom.

So, what accounts for the omission? E.R. fits the profile of several other influential shows – like Moonlighting (1985-1989), Northern Exposure (1990-1995) and China Beach (1988-1991) – that are absent in our current streaming environment. Since all of these programs were network shows from the late 80s and early 90s, there is something presumably “middlebrow” about their status as audience-pleasing works, no matter how complex or innovative they may actually be upon second glance.

E.R. also conforms to Jason Mittell’s criteria of what constitutes a “Great [television] Story” embodying both “narrative complexity” and “aesthetics of surprise.” This narrative and genre experimentation was characteristic of the show, not only in episodes when its characters left the hospital but in episodes that seemingly had straightforward plots. For example, in the first episode of season 4, entitled “Ambush” E.R. experimented by with a live episode and then did it again for the West coast audience.

Narrative innovation and experimentation accompanies some term papers most memorable episodes, where characters are killed off without notice (“Be Still My Heart,” “All in the Family,” Season 6 episodes 13 &14), where episodes play events backwards (“Hindsight,” Season 9, Episode 10), or where two opposing time frames converge with satisfying results (“The Lost,” Season 10, Episode 2).

Most episodes begin with a two-minute “oner” where the viewer is swept away into the center of the action. The skilled cinematographers, actors and camera operators made it look so easy that we have somehow forgotten what a feat it was.

Nevertheless, the show featured at least one bravura take per episode – executed with a skill and complexity that would leave even Alejandro González Iñárritu to nod his head with admiration.

[vimeo]http://vimeo.com/111416267[/vimeo]

Perhaps it is the presentist notion of television rhetoric that makes these shows so absent within contemporary scholarship. These shows all existed without internet buzz, making their cultural impact seem less important than today’s “quality” offerings. Since E.R. is also 15 seasons long, with an average of 23 episodes per season, it provides a significant challenge to analyze to the scholar.

Obviously, we need to recuperate E.R. within our critical canon. Opposed to other series’ that ushered in the moment that television became “legitimate,” there is something decidedly adult about the show which may not have spoken to the interests of scholars coming of age within the 1990s, but are highly relevant today. The show also served a mass rather than elevated demographic as in the example of The West Wing (1999-2006), whose viewership was significantly smaller, but whose niche audience provided dissertation writing it with critical, scholarly and network esteem. E.R.’s reputation also suffers without the presence of a bona fide showrunner-auteur at the helm. Despite his immense success with the series, Executive Producer John Wells figures into our history as more of a “company man” with solid credentials in the vein of Donald Bellasario, Aaron Spelling among others, but not in the ranks of writer-producers like Aaron Sorkin, Joss Whedon, or David Lynch.

Taking a closer look means admitting that the series moved beyond our shorthand perception as a mere medical show to a complex work that explored social issues in great depth. It also proves that it was the kind of show that we, as scholars, are constantly crying out for. Do we want intricate, responsible representations of people of color? Enter Dr. Benton (Eriq la Salle), Dr. Gallant (Sharif Atkins), and Dr. Pratt (Mekhi Pfifer). Do we want compelling, complex representations of women? Look no further than Nurse Carol Hathaway (Julianna Marguiles), Dr. Corday (Alex Kingston), Dr. Carrie Weaver (Laura Innes) or Abby Lockhart (Maura Tierney). Do we want social commentary about gun control, the faltering health care system, the Balkan War, AIDS treatment, disability, racism, gay adoption, the Iraq War, the turmoil in the Congo, or just about any other issue that was pressing essay writing in the 1990s/early 2000s? The show had all of these issues on its front burner, leaving no question as to its liberal bias nor its impetus for representing reality as accurately as its Chicago setting allowed for.

E.R., among other long-running network programs such as Law & Order (1990-2010), certainly deserve our scholarly attention. As a thought experiment we might also ask how E.R. would have fared in the twitter universe, or in the present “TV vs. Film” debate. What fandoms armed with hashtags might champion E.R. and how would its impact in our present moment be felt? Regardless of the answers to these questions, E.R. demands the look that it somehow never received in our current moment to write my essay for me— if only to teach and write about our field accurately.

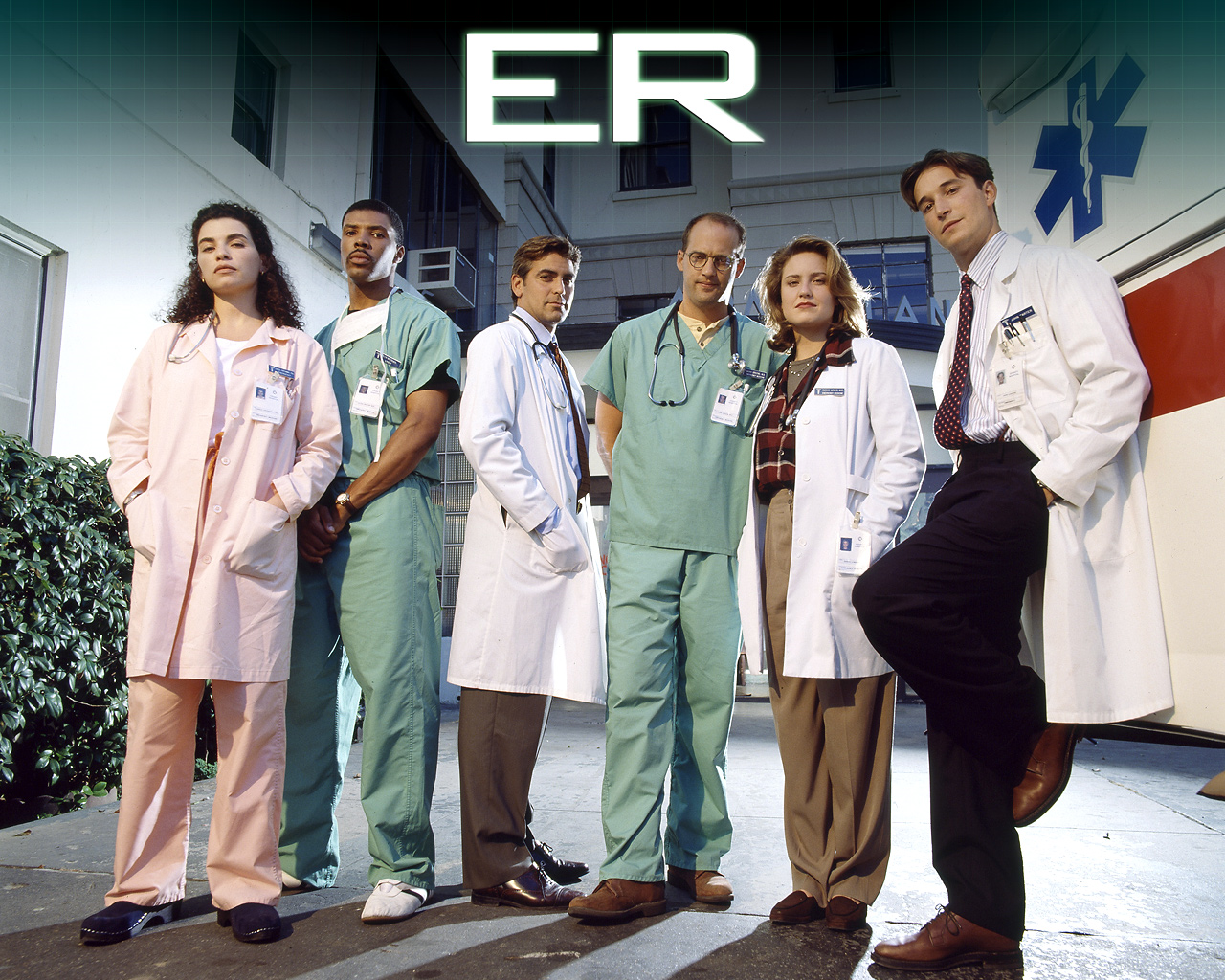

Image Credits:

1. E.R. Season 1

2. George Clooney’s star-making turn as Dr. Doug Ross in Season 2’s “Hell and High Water”

3. In the episode “All in the Family” two characters were suddenly stabbed, with shocking results for the series.

4. E.R. Season 11

Please feel free to comment.

- Littlefield, Warren, and T R. Pearson. Top of the Rock: Inside the Rise and Fall of Must See Tv. New York: Anchor Books, 2013. Print. [↩]

Pingback: The Chant | Longing for laser tag and the littlest pet shop: an analysis of 90s nostalgia

Pingback: These Are the 28 Highest-Grossing Television Shows of All Time – WORLDNEWS

Pingback: These Are the 28 Highest-Grossing Television Shows of All Time – FergPlace