Calling “Action” in the GoldieBlox Franchise Derek Johnson / University of Wisconsin – Madison

The GoldieBlox company emerged in 2012 amid an ongoing dialogue about the limitations with which major toy marketers imagined the play of young girls. The LEGO Group had gained significant attention that year for trying to look beyond its core target of boys to more explicitly connect girls to the construction-based play long credited with preparing children for careers in design and engineering. This move was heavily critiqued by feminist voices like Anita Sarkeesian’s Feminist Frequency and activist organizations like SPARK that shared LEGO’s goal but found counterproductive its emphasis on baking, shopping, caregiving and other normative gender scripts (as termed by Mary Kearney and Ellen van Oost).1 With the “What it is is beautiful” girl of the 1980s becoming a social media meme, GoldieBlox entered the market as a would be savior who could turn back the clock on the scripts that ruled the current toy market and reconnect girls with the pleasures of engineering. Each product in the line, from “GoldieBlox and the Movie Machine” to “Goldie Blox and the Dunk Tank,” presented young builders with a box of spindles, ribbons, axles, and cranks.

Vowing to “disrupt the pink aisle” logic of the industry, GoldieBlox garnered significant public attention via Kickstarter, promotional videos on YouTube, public battles with The Beastie Boys over unauthorized use of their song “Girls” in one of these videos, and even Super Bowl advertisement. Some public commentators have also thrown cold water on this would-be feminist mission by decrying the persistent pink-and-purple (and white and blond) cuteness of the GoldieBlox character displayed on the packaging to provide a feminized narrative frame for use of the construction materials. Others have simply pointed out how the toys are not that fun and have limited engineering functionality. What interests me most, however, is the announcement earlier this month that the company would add an action figure to its construction toy line. Both this new product and the announcement itself depend on a narrative of “action” well worn in the toy industry to distinguish boys’ playthings from girls’.

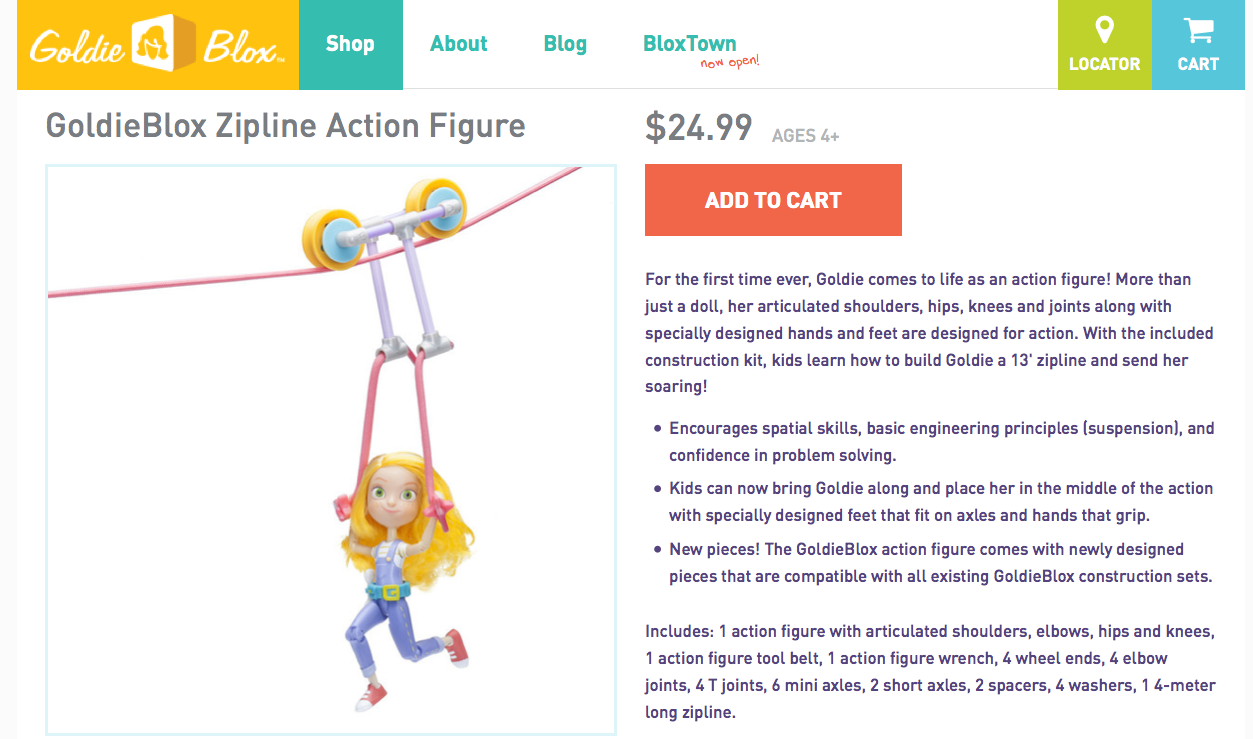

The “GoldieBlox Zipline Action Figure” brings new focus to the GoldieBlox character. While existing products did feature small animal tokens in addition to engineering components, Goldie herself remained two-dimensional—a figure featured on packaging, instructions, and marketing materials (including downloadable apps). In this action figure, Goldie gets a plastic form of her own. The figure includes new building pieces compatible with old sets, intended to construct a zipline carriage to traverse Goldie across whatever chasm can support the 13-foot cord (indeed, this seems incredibly fun). As promoted by the company, however, the focal point of the product appears here https://grademiners.com/dissertation-help to be Goldie herself and her difference from other human avatars for children’s play. “For the first time ever, Goldie comes to life as an action figure!” the product page boasts. “More than just a doll, her articulated shoulders, hips, knees, and joints along with specially designed hands and feet are designed for action!”

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fLO0eQuc-sQ[/youtube]

Besides extending the industry’s longstanding investment in action as a marker of distinction from traditional girls’ toys, this video extends the principles of ongoing television/video narrative by which many action toys have been franchised It is easy to imagine Goldie’s action heroine, good-versus-evil battle against the sinister organization Big Sister in the same vein as the never-ending conflict of GI Joe versus Cobra or Inspector Gadget versus K.L.A.W. As developed out of partnerships between toymakers, comic book publishers, syndicated television producers, and others in the 1980s, these serialized good versus evil narratives helped to build brands that could be marketed across media platforms. As much as I think Big Sister could present an ongoing narrative threat to Goldie, I’m not entirely convinced that’s exactly what the future will hold (still, it’s fun to imagine villains to add to the action figure line: The Patriarch? Backlash? Scareotype?). Yet already in operation across GoldieBlox’s television commercial and online videos is the construction of a good-versus-evil industry narrative. GoldieBlox the character only now stands in for GoldieBlox the company and its heroic struggle against established industry interests and beliefs—a struggle validated through the discourse of “action.”

Action is important. Activism, whether possible through the creation of new consumer products or not, requires it. Yet the GoldieBlox franchise, GoldieBlox company, and GoldieBlox character ask us to think about the degree to which culture industries have already defined the terms of “action” and articulated them to the gender distinctions upon which they construct markets. It’s definitely possible for GoldieBlox to deconstruct and recuperate the cultural and industrial privilege accorded “action” without buying into the gender hierarchies it has underwritten thus far; but I remain worried that in seizing onto terms of action long valued in articulation to boys without interrogating those values, GoldieBlox contributes to the continued devaluation of dolls on the basis of them being “for girls.” What instead would be the comparative politics of an “action doll”? Perhaps that would be the worst of all worlds. But I wonder nevertheless whether the action figure as imagined by the culture industries so far is up to the task of supporting more gender-inclusive imagination of play. I hope that subsequent attempts within the industry to improve these possibilities (by GoldieBlox or otherwise) will spend more time thinking not just about the politics of the doll, but also the relatively less explored politics of the action figure.

Image Credits:

1. The GoldieBlox action figure.

2. The website for the GoldieBlox Zipline Action Figure announces that “Goldie comes to life as an action figure!”

3. Advertisement for a 2010 art show in Lauderville, Florida.

4. The rogue woman brings down Big Brother in the landmark “1984” Apple commercial.

Please feel free to comment.

- Mary Kearney, “Pink Technology: Mediamaking Gear for Girls”, Camera Obscura 25.2 (2010): 1-39; Ellen van Oost, “Materialized Gender: How Shavers Configure the Users’ Femininity and Masculinity,” in Oudshoorn and Pinch (eds.), How Users Matter: The Co-Construction of Users and Technologies, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2003, pages 193-208. For more on this LEGO controversy, see my chapter “Chicks with Bricks: Building Creativity Across Industrial Design Cultures and Gendered Construction Play) in Wolf (ed.) LEGO Studies, New York: Routledge, 2014. [↩]

Interesting piece! While agree with the flaws you’ve found in the marketing of the action figure, I must admit that I’m still all for any toy that helps break up the astonishingly gender divided market. Last year, I nannied a six year old girl whose toys included Legos, toy cars, dolls, stuffed animals, train sets, and princess tea sets, crossing the gender divide. Yet, she still believed that pink is a “girl color” and refused to believe me when I said there were boys that liked pink and girls that hated it. Gender role conditioning is still incredibly present in consumer society and I think that Goldie Blox has received startlingly little media attention outside of niche circles.

I also think it’s interesting that we associate “action” with boys and the action figure, and yet dolls are for more interactive, if not “active” in the traditional sense. I think of action figures being posed, played with or maybe battled. Dolls on the other hand can be held, dressed, have their hair styled, and even talk, cry, and drink water. Yes, these are traditionally feminine activities, but the interactivity factor is still interesting to think about.

Pingback: Testimonial Blog