Ice Beauty, Dancing Beast: Women Athletes, Showmances, and Dancing with the Stars

Kathleen Battles / Oakland University

After mounting two seasons a year for 9 years, by 2014 Dancing with the Stars (DWTS) was suffering the natural exhaustion all reality formulas do and increasing trouble locating bona fide “stars” to compete. In the absence of stars, the program increasingly relies on a number of canned, well-worn, easily available story arcs that add dramatic tension and keep viewers engaged in spite of inconsistencies in talent and performances. These narratives are constructed by the producers through weekly filmed rehearsal “packages,” the dancers and stars, the program’s judges, and audiences. In a competition centered on intense relationships between opposite sex dance partners – one positioned as a teacher, the other as student – heterosexual romance – the showmance – reigns supreme.

The DWTS showmance is strongly shaped by a key tension in the gendered discourses of ballroom dancing: on the one hand, dance teams are almost always opposite sex pairs whose performances involve hyper performances of heterosexual desire; on the other, male performers are frequently scrutinized as to whether they are, in fact, heterosexual. Intense fan scrutiny of dance pairs’ relationship status becomes a key way to resolve such tensions. The intensive physical, mental, and time demands of the series, which requires presumed novices to master ballroom dance techniques and learn a new dance a week, undoubtedly fosters close ties between the dance professionals and their celebrity partners. The “showmance” occurs when there are any hints of romance between stars and pros. Playing off the “will they or won’t they” trope, a key television narrative device at least since the days of Moonlighting, a well-played “showmance” can guarantee fan support.

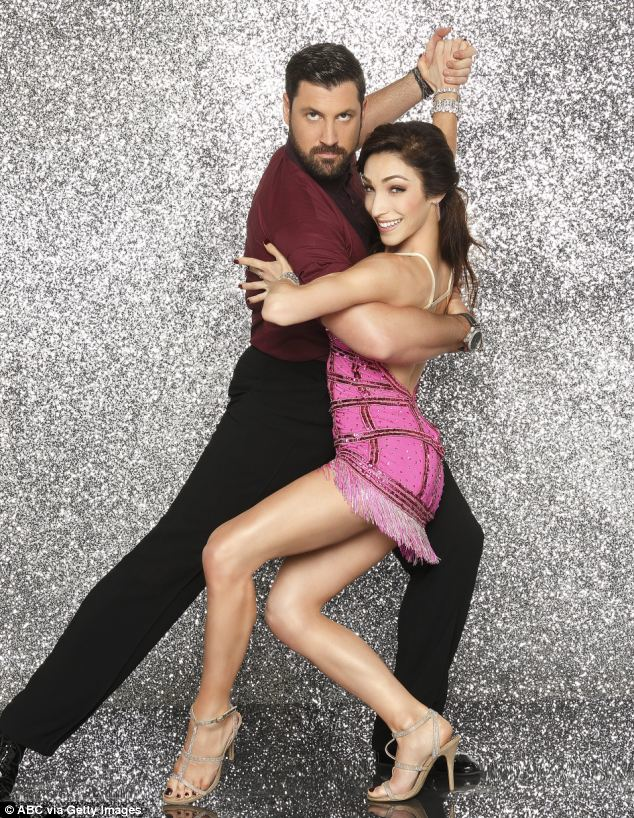

Season 18 began with a leading contender for showmance of the season, as contestant James Maslow was paired with pro dancer, Peta Murgatroyd, after the two had reportedly dated. Enter the ringers, Sochi Olympic gold medalist ice dancing pair, Meryl Davis and Charlie White. Quickly, the relationship between Davis, and long time series pro, Maksim Chmerkovskiy emerged as the dominant showmance of the season. While Davis’s dancing prowess was to be expected given her background, the unexpected chemistry between the quiet, calm Davis and the loud, quick to anger Chmerkovskiy was increasingly read as a tale of Beauty and the Beast, and constructed as a redemption narrative of the pro, effectively reducing the contestant to supporting player. In the process, Davis’s own accomplishments as an athlete were consistently placed as second to her relationship with her dancing and skating partners.

From the start, Davis was situated first and foremost as “partner” to her male counterparts. Publicity in the week’s leading up the show continually tried to emphasize that Davis and her skating partner, Charlie White, also a contestant, would now be pitted against each other. Like ballroom dancing, ice dancing is performed by opposite sex pairs who are often read as potential romantic partners rather than teammates. The 17 year partnership between Davis and White was already the source of intense speculation, and the pair had a devoted following of shippers, presuming or wishing that they were a couple.1 The fact that the skaters would now be performing with different partners was treated as a possible threat to their relationship. Pre season publicity for Chmerkovskiy, focused on the DWTS pro’s bad boy reputation, earned for his quick temper and contentious relationship with the judges. In fact that relationship had grown so contentious that Chmerkovskiy was returning to the show after a two-season absence with a desire to clean up his act. The filmed “package,” purportedly capturing the first meeting between the pair quickly establishes Davis’s currency, as Chmerkovskiy asks her if she is dating White, and expresses his instant attraction and satisfaction with her obvious talent.

Over the next few weeks, the pair increasingly becomes situated within a beauty and the beast narrative. Tall, “dark”, bearded, muscular, and hot tempered, the Ukrainian native Chmerkovskiy’s rugged masculinity was the exact opposite of the blonde, slight, clean shaven, perpetually cheerful and upbeat Charlie White’s boyish masculinity. Chmerkovskiy was a beast, and the beautiful, ethereal, and ever-unflappable Davis was set up as his saving beauty. In the week 6 rehearsal package, viewers hear Davis express dismay at their low scores from the week before and see her competitive spirit kick in. However, as the package proceeds, we witness Chmerkovskiy grow increasingly frustrated so that Davis ends up comforting him, letting him know that they can support each other. This narrative of transformation is further highlighted by judges’ comments, especially from Carrie Ann Inaba, who excitedly tells the pair that they bring out the best in each other.

During week 9, the beauty and the beast narrative reaches a critical point. In the rehearsal footage, we first see Davis get a visit from her idol, figure skater and former DWTS contestant, Kristi Yamaguchi, to talk about her experience on the show and handling its unique pressures. But the attention quickly turns to Chmerkovskiy’s temper. Telling her that he feels the stress of having the best dancer on show, we see him get angry during rehearsal, frustrated that Davis cannot learn her steps. After throwing his microphone towards the camera operator, we see a confessional of Davis explaining away his behavior, and finally a scene of her flirtatiously giggling and trying to distract him and get him out of his mood.

By the finale, weeks of intense media speculation, impressive performances, and carefully curated video packages had created a seemingly unstoppable showmance train. From questions by the producers through comments from the judges and hosts, marriage emerges as the only possible conclusion, despite the fact that the pair had neither confirmed nor denied that they were even dating. Producers query both on their future, and while Davis hedges, Chmerkovskiy, cheekily declares his desire to have “big Russian babies” named Boris and Oleg with Meryl. Erin Andrews interviews them right after they see the tape, and we see the beastly Chmerkovskiy, finally tamed. Even host Tom Bergeron jokingly refers to him as the “Blushing Russian.”

During the pair’s final “freestyle” dance, they come close to, but never actually kiss. Well, is there anything more tantalizing that denied consummation? The intensity is too much for judge Carrie Ann Inaba. Overcome with emotion, she blurts out what no doubt many fans had been wishing, “first of all, I think you should get married!” The desire of romantic closure is heightened when host Erin Andrews cheekily teases the pair about their non-kiss.

Other moments in the competition continued to highlight Davis’s status as currency. During week 4, in an attempt to add interest to the formula, the show’s producers decided that contestants would switch partners. In this case, Davis moved from being paired with Maksim Chmerkovskiy to his brother and fellow DWTS pro, Valentin Chmerkovskiy. In the rehearsal package we witness a jealous Maksim, upset to see how well Valentin and Davis are dancing together. And while the program generally downplayed the competition between Davis and her long time skating partner, White, they were purposely pitted against each other in the semi final elimination round. Placed on stage as the last two to hear their fates for going forward to the final, they are told that they do not necessarily have the lowest number of votes, but that one will be going home. White publicly expressed his frustration with producers afterwards.

Were Davis and Chmerkovskiy romantically involved? Were they cynically playing up the showmance for ratings and votes? I personally suspect the truth the lies somewhere in between. But there can be no doubt that the pair were formidable competitors with a natural chemistry that easily translated to the screen. Of course, they are each trained to perform such chemistry as a key to their professional success. The point here, however, is the sometimes disturbing way that their narrative was presented. Rather than situated as a professional, accomplished athlete (though to be fair, the judges often praised her dancing abilities), in the constructed discourses of the show Davis was reduced to currency traded between her male partners. The troubling beauty and the beast frame discursively stripped her of any agency beyond her function of helping her dancing partner achieve his goal of mirror ball victory. This is not to say that this was the experience of the pair themselves, but rather speaks to our broader cultural investment in a narrow set of gender norms in which women and athlete continue to remain incompatible categories, and in which heterosexual romance is reinforced as a woman’s truest desire and greatest accomplishment.

Image Credits:

1. Meryl Davis tames the beast, Maksim Chmerkovskiy

Please feel free to comment.

- There are any number of fan fiction stories and videos on line. See for example, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sx3O-NnBFSg [↩]

I really enjoyed your discussion of the beauty and the beast narrative as a way to understand Maks and Meryl’s showmance narrative. I think the context of Disney as the parent company of ABC makes this particularly salient. Of course they are interested in forwarding a certain flavor of princess/romance type story within DWTS that matches with their larger brand. I appreciate your discussion of the negative aspects of that narrative. In particular, some of these clips were really disturbing in terms of the “beast” narrative that let his abusive sort of behavior be explained away by Meryl and/or justified by their “love” as demonstrated through their dancing. I didn’t watch the show, but even in these short clips, I could feel the back and forth pull of the beauty and the beast narrative and emotional drama that makes shows like this so popular. Great piece!

I just wanted to respond and say I really love this piece. The fact that I don’t Olympic athlete could somehow have her athleticism made secondary is quite a narrative accomplishment. It speaks to the nature in the power in danger of these narrative troops as they are laid out in these kinds of shows. This to me acts as a template of what to look out for. I’m definitely using this with my classes in the future. Thank you so much!

A quick correction for the above post, which I made on a phone. Ugh:

I just wanted to respond and say I really love this piece. The fact that an Olympic athlete could somehow have her athleticism made secondary is quite a narrative accomplishment. It speaks to the nature in the power in danger of these narrative troops as they are laid out in these kinds of shows. This to me acts as a template of “what to look out for when watching DWTS or any other competition show that involves athleticism and heteronormative coupling”. I’m definitely using this with my classes in the future. Thank you so much!