Past Media, Present Flows

Derek Kompare / Southern Methodist University

Every Flow conference is fueled by enduring, yet always-shifting, questions of what constitutes television, and how we try to understand it. This year, from Horace Newcomb’s attempts to pin down veteran TV writers and critics on the question of television as a broad cultural forum, to Kevin Reilly’s admitted bewilderment at the function of audiences, the discussions largely centered around the changing relationships between viewers and medium (if we can still call something distributed and consumed through many different platforms “a medium”). In the panels I attended and participated in, the questions were largely ones of distribution and access: Does television “flow” the way Raymond Williams described it in 1974, or is it predominantly an ad-hoc, on-demand system? What are the politics of enunciative fandom in an era of (supposed) geek domination over media? Who now controls access to content and users?

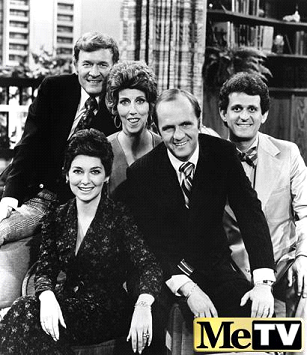

I’m primarily interested in what happens to past media within all this change. This concern entails not only with the “whats” of preservation and recirculation (i.e., whether or not a particular work is saved), but also the “hows” and “whys”: How is an older work restored and accessed? Why is there so much variation in restoration and access? In an age of seeming media ubiquity, we often assume that most past media works are readily available at a few keystrokes and mouse clicks. However, as with so many other “hidden” parts of our media systems, this presumption glosses over the complex processes involved in preserving, restoring, redistributing, and consuming past media. Many decisions and practices have shaped the availability of that episode of The Bob Newhart Show you’re watching on Hulu long before you’ve clicked on it.

While such streaming and/or downloading garner the most attention today, viable methods of distributing and viewing any kind of television still include successful systems established decades ago, including over-the-air broadcasting, cable, satellite, and physical media. While those who wish to appear tech-savvy will disregard older methods, asking “who does that any more?!?” or making classist jokes at the Emmys about VCR usage, most of these methods are still quite relevant today. However, they each still matter in different ways, and as scholars and (more precisely) historians, we need to attend more carefully to how these methods relate to each other in shifting media environments.

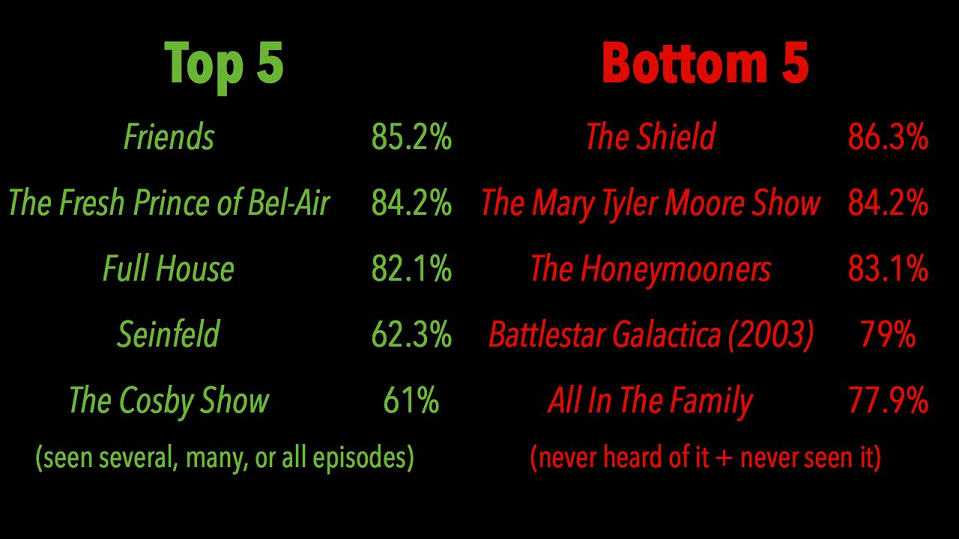

In my core conversation talk, I discussed a survey of 95 of my students this year that had gauged their exposure to older TV shows. While space doesn’t permit a complete description of the results, it was clear that continuous runs of shows on cable channels like TBS, USA, and Nickelodeon had mattered more to my students (all aged 18-25) than the mere presence of a title on a streaming service or as a DVD box set. In this case, a wide majority of students were very familiar with Friends and The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air, but very few had even heard of all-time TV classic The Mary Tyler Moore Show, or hard-edged 2000s critical darling The Shield.

While admittedly this isn’t a robust sample of changing perceptions of TV, it still suggests that we need to consider how we’ve experienced television in the past as much, if not more, as how we’re experiencing it now. TV shows aren’t isolated bundles that are encountered on their own, but texts that always come embedded in particular industrial and cultural contexts, whether broadcast schedule, journalistic retrospective, tumblr blog, streaming choice, or, yes, media studies syllabus. These always-shifting contexts determine how viewers encounter past media; de facto canons (e.g., as generated by us media scholars) are relatively tiny pieces of those contexts.

Accordingly, barring radical change to the economy, the market terms of our media culture cannot be overstated: there will always be sellers and buyers of media. Sellers always produce and/or obtain new works, but will only continue to offer old works if they perceive some buyer demand for it (“buyers” running the gamut from channels or services looking for programming to attract advertisers or subscribers, to fans wanting to own physical copies of their favorite shows). While the conditions which trigger that demand, and the seller response to it, are certainly complex, the general case for marketing a library or “back catalog” of content for a seller, as I argued in Rerun Nation, is that it is a) potentially easier to sell, since it has already made an initial appearance in the culture, and b) potentially more profitable, since production costs may have been paid off years or decades ago. Moreover, for decades new media technologies, ranging from UHF TV to cable channels to home video to the internet, have always been launched into prominence largely through old media.

Indeed, one particular category in the US, the broadcast digital subchannel, or “digi-net,” has greatly expanded in the five years since the HD conversion and reallocation of broadcast frequencies. National networks specializing in past television, like Cozi TV, MeTV, Antenna TV, Hot TV, and Retro TV, have effectively recreated the rerun-heavy independent station of the 1960s-80s. While their audiences are tiny, and their availability is often spotty (e.g., many cable systems don’t bother to carry them at all), they have been lucrative enough to warrant expansion and even generate their own fan bases. As I mentioned in my Flow talk, because of these channels, the golden age of over-the-air reruns is apparently right now; Dr. Hartley is in session on Monday nights on MeTV.

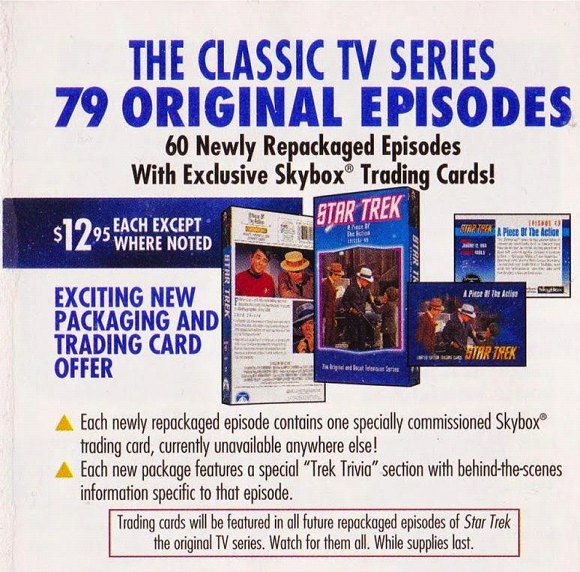

Because of both audience fragmentation, multiple distribution platforms, and more precise data analysis, viewers, as fans, increasingly factor into the availability of past television, even of less prominent titles. Music and video publisher Shout! Factory has long based its business around licensing and redistributing past media directly to fans. Time-Life and Warner Archive (as I’ve previously examined) also specialize in selling otherwise marginal titles to fans. At the conference, this commercial role of fans (as potential consumers, rather than “textual poachers”) came out in discussions with Ryan Adams and David Grant from CBS Multimedia Services, who oversee most of that studio’s television restoration and repackaging. They indicated that while their work orders generally come from “above,” i.e., from CBS’ program marketing, they also seek input and feedback from fans of older shows. They claimed discussion with fans at Star Trek conventions has helped shape the production of the remastered Trek series on HD and Blu-Ray. At Flow, at least two TV fans–each prominent media studies scholars–approached Adams and Grant at the conference with a request to exhume Frank’s Place, the critically-acclaimed but otherwise long-forgotten 1987-88 CBS dramedy about a fish-out-of-water Ivy League professor running a New Orleans restaurant.

Even if distribution is possible, the particular form the past media work takes on its return is certainly variable. The technical standards of television images and sounds have changed drastically over time, and this poses a particular challenge for older material. At the conference, Adams and Grant displayed before and after clips of the HD conversion work they oversaw on Star Trek and Star Trek: The Next Generation. While the film restoration work of live-action shots (from original camera negatives) is meticulous and impressive, the creation of new, CGI special effects shots, while necessary for the latter show to match the higher resolution, does replace existing material, though as close to the spirit of the original shots as possible. I agree with Adams that pragmatism has to meet idealism at some point, and the new shots are certainly better than not getting the show at all. Still, CBS’ cost-saving decision to split the restoration of seasons between their own, outstanding digital crew, and various outside firms, has resulted in some problematic differences. However, rather than follow an impossible quest for a commercial release of somehow unmodified “original versions” of material, we should appreciate the transactions necessary to bring them back out at all, and approach new versions as new textual iterations of the original work. These iterations will be almost certainly different than the original, and marked by their own contexts of production, but ideally still resonant enough to effectively represent the past for each present. Our task, as media historians, is to not take past media for granted, but work to understand more of how redistribution works, and help provide context along the way.

Image Credits:

1. Core Conversation 2, Courtesy of Kyle Wrather.

2. What are students watching, Graph submitted by Author.

3. Star Trek VHS

4. Bob Newhart Show

5. Frank’s Place

Please feel free to comment.