Without Warning

Melinda Barlow/University of Colorado at Boulder

Once in a Lullaby (Josh Minor, 2008)

It hit. Hard. Late at night. Some thought it sounded like a freight train; others assumed it was a low-flying jet. One woman recognizing the familiar roar simply said “It’s a wind acomin.’”

People lit out for storm cellars, dove under beds, cowered in back rooms, ducked for cover. The air was dead still and full of dust; many could not breathe. Some were pummeled by hail and debris. One man went to sleep and woke up in the street, unclear how he got there. Another, returning from an errand in his car, never made it inside because “the house started leaving.”

Buildings cracked open, windows flew out, the water tower toppled, and the grain elevator collapsed. A telephone operator died at the switchboard. The most famous photograph shows a pickup truck, stripped of everything but its frame and tires, tipped on end, wedged up a tree. The driver was found dead a quarter mile away.

A police chief saw it coming and tried to radio ahead, but the town did not have a police radio then. A train engineer spotted it and blew his whistle as an alert. “We’re all going to be blown away,” one woman cried, “I wish I could call everyone and warn them.”

On May 25th, 1955 at 10:35 p.m., a tornado three-quarters of a mile wide blindsided Udall, Kansas, a small town twenty-five miles southeast of Wichita. Within minutes 80 people were dead and 270 were injured. 192 buildings and 170 homes were destroyed. Although severe weather warnings had been issued in the morning and afternoon, more heavy rain prevented the National Weather Service in Wichita from detecting the approaching funnel, and the weather bulletin issued from Kansas City expired at 10:00 p.m. A television station reported that severe weather had passed.

Now considered an F-5, the highest and most dangerous rating on the not-yet-established Fujita scale for measuring tornado strength, the twister that tore through Udall at 300 miles per hour is still described as the deadliest in Kansas history.1

What a nightmare.

Title Credit from Star 34 (Herk Harvey and Arthur H. Wolf, 1954)

Learning about Udall landed me back in Kansas, where I was born, both the Sunflower State of myth often made to stand for all that is wholesome and decent and ordinary in mid-20th century American films, and the dark and bleak Kansas of Truman Capote, Herk Harvey and Salman Rushdie, a place of apprehension and imagination, where Dorothy Gale’s Auntie Em anxiously watches the sky, and great whirlwinds arise. Star 34—“the 34th State in the Union, with the 34th President, and a star in its own right!”—as enthusiastic easterner Bill Asher, played by Harvey, puts it at the end of the eponymous industrial film made by the Lawrence-based Centron Corporation in 1954, Kansas is also home to Holcomb, the village on the high wheat plains of the west, a lonesome area, writes Capote, that “other Kansans call ‘out there.’”2That Kansas, and what happened there in November 1959, has something in common with the Kansas that Rushdie, in his compelling essay on The Wizard of Oz (Victor Fleming, 1939), calls “that great void,”3 and that Harvey as Asher (the same Harvey who would direct the cult horror film Carnival of Souls [1962], shot in Lawrence and at an abandoned amusement park in Utah), when told he must visit there in order to qualify for an inheritance at the outset of Star 34, calls “nowhere.”

As Rushdie points out, Kansas gets but a few pages at the beginning and end of L. Frank Baum’s book (1900), and this puts to the lie the “conservative little homily”4 “there’s no place like home” with which the film ends. Because both book and film linger in Oz, Rushdie sees it as Dorothy’s real home, and Fleming’s film as a paean to the human dream of leaving, a dream “at least as powerful as its countervailing dream of roots.”5 This is a persuasive idea, one that questions Baum’s claim in his Introduction to have written a “modernized fairy tale, in which the wonderment and joy are retained and the heart-aches and nightmares are left out.”6

Once in a Lullaby (Josh Minor, 2008) also upends this claim, reversing the chronology of Fleming’s iconic film, distilling its underlying darkness into a glowing five-minute gem of condensation and displacement, described by Minor as a “dream gone wrong.”7 In his film’s opening images, Dorothy is already in Oz, already dreaming. Glinda never appears, and Dorothy never leaves, although the glistening orb that heralds the arrival and departure of the Good Witch in the original serves as the vehicle of transport for our entry into and exit from Dorothy’s anxious unconscious imaginings. By saturating the black-and-white sequences which take place in Kansas with extraordinary colors, transforming the Technicolor which is Oz into an even more lurid and spectacular realm, and adding a score of reverberant chimes and ambient drones, Minor creates the unsettling sensation of being trapped in a nightmare that never ends. Backlit by a gold and amber sky resembling smoldering embers, the famous tornado snaking through the prairie never looked so menacing.

Annie Strader, Christine Owens, and Emily Bivens in Warning Signs II (The Bridge Club, 2014), detail

How to read the sky? What are the telltale signs of an oncoming F-5? How to analyze the data, alert the public, take precautions, and survive, a tornado or any other calamity, atmospheric, personal, or otherwise? In “Warning Signs II” (2014), a performance by The Bridge Club at the Ulrich Museum of Art in Wichita at the end of April, in tornado season, Emily Bivens, Christine Owen, Annie Strader and Julie Wills donned their familiar wigs, this time wearing black shifts, and stood sentinel in the Museum’s courtyard, frequently gazing skyward while performing a series of mysterious tasks.8

One woman traced and simultaneously erased locations in an atlas with sandpaper-tipped gloves; another held a cone to her mouth filled with a recording of wailing wind, sending out a symbolic siren sometimes drowned out by the real gusts picking up during that late April evening. Together the women measured and created radiating lines with chalk dust, then partially removed them with spoonfuls of water.

Emily Bivens in “Warning Signs II” (The Bridge Club, 2014), detail

Later, a miniature storm projected on the side of “The Trailer,” its pink and yellow clouds punctuated by tiny forks of lightning, offered a safe, beautiful, luminous souvenir of a potentially threatening situation. Like the volunteer network of “experienced observers at their stations, watching” in the industrial film Tornado (Calvin Productions, ca. 1955), the members of The Bridge Club searched the sky for clues of forces that cannot be controlled, that might strike without warning.

Candace Hilligloss as Mary Henry in Carnival of Souls (Herk Harvey, 1962)

An inexplicable force takes hold of Mary Henry in Carnival of Souls, one that sometimes makes her feel that she no longer exists, and has no place in the world. Unaware that she has driven off a bridge in a drag race, and may or may not be dead, she emerges from a river unsure what has happened to her, and the women she was with. A church organist who takes a job in Utah, insisting that she is never coming back to the town in Kansas where she went to school, her move out of state is haunted by a white-faced ghoul simply called “The Man” (Herk Harvey), who somehow appears instead of her reflection in the windows of both her car and new rooming house (really located in downtown Lawrence, so in some sense Mary never leaves).

In one stunning nocturnal sequence, when The Man disappears, Mary suddenly sees herself, split, her furrowed brow attesting to what she does not understand, the doubling of her image a striking visual reminder of her schism with the world. No wonder she tells a fellow boarder who doggedly pursues her that it is at night when “fantasies get so out of hand.” Her solution to this problem? “Let’s have no more nights!”

Candace Hilligloss as Mary Henry in Carnival of Souls (Herk Harvey, 1962)

But daylight can be full of equally strange occurrences, as her stroll through an abandoned amusement park on the shores of the Great Salt Lake makes clear. One part of this sequence potently evokes her predicament: walking through a Rotor ride long without motion, an aperture-like structure turned on its side, she is, dead still, at the center of a vortex, no longer living, possibly dreaming, the I of a storm who does not survive.9

The Clutter House at night in In Cold Blood (Richard Brooks, 1967)

None of the Clutters survive the ravage wreaked upon their home in Holcomb by Dick Hickock and Perry Smith in the dead of night on November 15th, 1959. Driven by distinct yet related dreams—Hickock by the fantasy of a perfect score, a farmer with a big spread and a safe full of cash, Smith by the promise of buried treasure, nurtured in his childhood by his rodeo performer father—the two have-not ex-cons touch down in the mythic heartland of Kansas (“the land of wheat, corn, Bibles, and natural gas,” in Hickock’s phrase) and kill all four family members in cold blood.

Why do they do it? This is what troubles Alvin Dewey, chief investigator on the case, and a fictional reporter named Jensen who serves as his foil in Richard Brooks’ 1967 film, otherwise fairly faithful to Capote’s true crime non-fiction novel published two years earlier. “A violent, unknown force destroys a decent, ordinary family. No clues. No logic. Makes us all feel vulnerable, frightened,” says Jensen to Dewey as they ponder the reasons for the crime. Perry Smith likewise questions his own motives and marvels at the inexorable unfolding of events, fuelled by his, and Hickock’s, lethal lack of control: “The whole crazy stunt had a life of its own,” he tells Dewey, “Nothing could stop it.” The shot following the final off screen shooting of young Nancy Clutter vividly brings this to life: a tumbleweed whirls at incredible speed past the killers’ car outside the Clutter house on that dark and windy night.

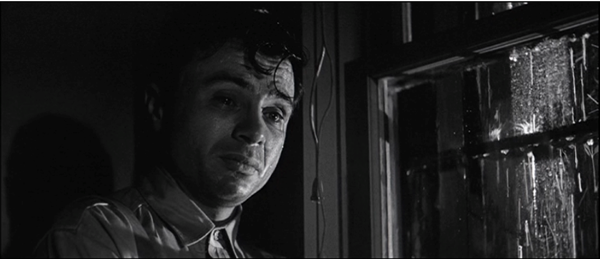

Robert Blake as Perry Smith in In Cold Blood (Richard Brooks, 1967)

The black hole at the center of all dark depictions of Kansas, Richard Brooks’ film, shot on location at the former Clutter home by veteran cinematographer Conrad Hall, achieves its visual apotheosis in the scene just prior to Smith’s execution, during a long poignant monologue he delivers to a priest. Here, Hall exquisitely captures the tormented murderer’s internal divide in the famous shot reflecting the rain outside the window onto Smith’s cheek, thus allowing him to release the tears he feels but cannot unleash as he mourns, with understandable ambivalence, the loss of his abusive, alcoholic father, that “poor old man and his hopeless dreams.”

William Holden as Hal Carter and Kim Novak as Madge Owens in Picnic (Joshua Logan, 1955)

In the dreamy heat of a Kansas late summer night, darkness can also unleash illicit desire, and this is precisely what happens in Picnic (Joshua Logan, 1955). Based on William Inge’s 1953 Pulitzer Prize winning play, the film was shot on location all over Kansas, including Halstead, Nickerson, Sterling, and Salina, starting on May 16th, 1955. When the historic tornado hit Udall nine days later, the cast and crew were 75 miles away, in Hutchinson, and the entire shoot was interrupted almost daily by hailstorms and wailing tornado warnings, meaning that the steamy final scenes at the picnic were completed on a Hollywood soundstage rather than in situ.10

Nonetheless, everything in this film is hot as soon as drifter Hal Carter (William Holden) comes to the fictional town of Salinson, and although slightly misleading, one of the film’s tag lines captures the tornado-like velocity of his effect on every woman around him, including Madge Owen (Kim Novak): “From the moment he hit town she knew it was just a matter of time.” Well, not quite. Madge eyes Hal with shy interest, to be sure, but so does her sister, mother, boarding house owner Mrs. Potts, and aging grade school teacher Rosemary Sydney, and indeed, one of the most amusing riffs in the script is the number of times Holden as Carter is forced to take off his shirt, so that all of the women in the vicinity may ogle him even more.

William Holden as Hal Carter and Kim Novak as Madge Owens in Picnic (Joshua Logan, 1955)

Before Miss Sydney famously tears that shirt in a fit of drunken rage, Hal and Madge do a remarkably sexy dance on a platform by the river, strung with colored lanterns, beautifully shot by James Wong Howe. All the more erotic for the mood of yearning that courses through its classic mid-50s restraint, the “Moonglow” dance number, played out to a sultry jazz standard transformed by composer Morris Stoloff, serves as a tantalizing prelude to the startling shot of Hal and Madge after the picnic, in a tortured embrace on the banks of the river, punctuated by the roar of an oncoming train. The Production Code Administration required that any suggestion that Hal and Madge had slept together after the picnic be cut, but this image stands in for what could not be shown, allowing it to explode through sexualized mise-en-scène. The shot thus provides a libidinous example of what one writer, in a broader exploration of the value of darkness and a need for sensitivity to nocturnal rhythms, evocatively describes as “the singing and blooming of the night.”11

Once in a Lullaby (Josh Minor, 2008)

We need the night. We need its obscurity, ambiguity, and shadow-filled beauty. Our souls and skins crave moonglow. We also need the night’s uncertainty, perhaps even its anxiety, and we always need to dream. And maybe, like Dorothy at the end of Once In a Lullaby—hand in her mouth, orb in her eye, coming and going in a world of clashing colors—sometimes we even need to be at odds with ourselves, if we land in a dream gone wrong.

We pick up. Move on. Put down new roots. Leave again. Return once more. Feel the winds of change and try to read the signs as we become more attuned to the meteorology of memory.

Family photograph, found in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 2007

Lawrence, Kansas. Where I was born. This photograph, its own strange rainbow.

For my mother and father, and what began in Kansas, and my whole family, found.

Image Credits:

1. Once in a Lullaby (Josh Minor, 2008).

2. Title Credit for Star 34 (Herk Harvey and Arthur H. Wolf, 1954).

3. Annie Strader, Christine Owens, and Emily Bivens in “Warning Signs II” (The Bridge Club, 2014), detail. Photo credit: Matthew Weedman/Artisan Photo.

4. Emily Bivens in “Warning Signs II” (The Bridge Club, 2014), detail. Photo credit: Matthew Weedman/Artisan Photo.

5. Candace Hilligloss as Mary Henry in Carnival of Souls (Herk Harvey, 1962).

6.Candace Hilligloss as Mary Henry in Carnival of Souls (Herk Harvey, 1962).

7. The Clutter House at night in In Cold Blood (Richard Brooks, 1967).

8. Robert Blake as Perry Smith in In Cold Blood (Richard Brooks, 1967).

9. William Holden as Hal Carter and Kim Novak as Madge Owens in Picnic (Joshua Logan, 1955).

10. William Holden as Hal Carter and Kim Novak as Madge Owens in Picnic (Joshua Logan, 1955).

11. Once in a Lullaby (Josh Minor, 2008).

12. Family photograph, found in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 2007.

Please feel free to comment.

- The facts herein, including the remarks made by survivors, come from multiple accounts of the tornado that struck Udall, Kansas in May of 1955. Some facts occasionally differ (e.g. death toll vs. number of survivors). See the following for more information: http://www.crh.noaa.gov/ict/udall/udall.php; http://www.kshs.org/kansapedia/udall-tornado-1955/12225; http://www.cityofudall.com/history-of-udall.htm; http://eldoradofd.com/1955-udall-tornado-survivor-who-is-she/; http://www.freerepublic.com/focus/f-news/1408292/posts. [↩]

- Truman Capote, In Cold Blood (New York: Vintage Books, 1965), 3. [↩]

- Salman Rushdie, The Wizard of Oz (London: British Film Institute, 1992), 21. [↩]

- Ibid., p. 56. [↩]

- Ibid., p. 23. [↩]

- L. Frank Baum, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (Chicago: George M. Hill Company, 1900), 5. [↩]

- Josh Minor, description of Once in a Lullaby. [↩]

- For more on The Bridge Club, see Melinda Barlow, “When Sleepers Wake and Yet Still

Dream,” Flow, 20.01 Volume 20 (July 2014), and Melinda Barlow, “The Guise of Good Behavior,” in The Bridge Club (art catalog), (Berkeley: Edition One Books), forthcoming, 2014.

[↩] - Bruce Kawin provides an illuminating reading of the film in his essay for the Criterion DVD of Carnival of Souls released in 2000. He describes Mary Henry as a “liminal protagonist” characteristic of the horror film, one who has “gone wrong, and the world with her.” See Bruce Kawin, “Carnival of Souls.” [↩]

- Rosalind Russell, who plays aging grade school teacher Rosemary Sydney in the film, campaigned for the Kansas Disaster Relief Fund established after the catastrophe, and a street in Udall was renamed for her as a result. [↩]

- Akiko Busch, “The Solstice Blues,” The New York Times, June 20th, 2014, I am indebted to this lovely rumination on the value of night for my own closing meditation in this essay. [↩]

Melinda, fascinating read!

I enjoyed how you explored some of the darker aspects of Kansas – the state of your origins. I find it true that Kansas has become this stock location for “all that is decent and wholesome”. The Holden character you mention seems to have that simple, all-american charm. Kansas was, after all, the setting for the novel Little House on The Prairie and even served as the adoptive home of the young Superman, who lived in the quaintly titled ‘Smallville’. Little House on the Prairie glorifies the simplicity of the American heartland. Superman, a figure pent up with so much American machismo, also finds simplistic origins in Kansas. Buster Keaton born in Kansas as was Charlie Parker. But Keaton, Parker and Kent all left the quiet state for a more kinetic environment.

There’s something blissfully bucolic about Kansas, it can be easy to forget the Sunflower State has to deal with Tornadoes, one nature’s deadliest weapons. Minor’s film adds a dark spin on the original beloved classic, but it’s a perspective that emphasizes the treachery of the setting, which Fleming’s film uses as serene bookends. The Udall story was harrowing but sparked my curiosity. To imagine all the destruction from a single event inflicted upon this town is unbelievable. Events such as that, which are so ephemeral, leave their mark embossed into the memories of the survivors. But, most of us outsiders are oblivious to that destruction.

My father was born in Fort Riley, Kansas, so for me, there is some romanticization of the farm culture and simple way of living. I went myself to visit the state for the first time last year, and was impressed with it spaciousness. I wondered just how many of the places we passed had served as a literal stomping ground for a deadly twister. To think, a tragic concoction of air temperatures and pressures can create such a unique force which continues to feed itself until it has been satiated. Nature’s own vicious circle.

Interesting that the Mary Henry character is so reluctant to return to her Kansan roots. It reminds me of this William S. Burroughs quote, “I am getting so far out, one day I won’t come back at all.“. Burroughs, interestingly enough spent a goof deal of time in Lawrence. For him, it was the perfect place to escape following the endless clamor in cities. I think many of us have been usurped by our homeland, though some try and resist it’s grasp. Mary attempts to escape and gets stuck with it’s unfortunate side effects.

Unfortunately, something about that geography of that state has made it a breeding ground for events like that; it’s a juxtaposition of serenity and simplicity. Your retroversion yielded a freshly fermented perspective which, propelled by a tragic event, led you to find the “yang” to the “yin” that helps provide a better picture of the state. Your sojourn provided you insight into what truly lies “over the rainbow” and It was amazing to read about your cinematic associations to the place.

Enjoyable read! Thanks so much,

Branson Stowell

Melinda,

I remember reading the Rushdie book and seeing Josh Minor’s film in Cinema, Magic, and Wonder and thinking about the aesthetics of the Wizard of Oz and the way it depicts female power in it’s various forms. What I like about this piece (and the previous one) are the many dualities: masculine/feminine, light/dark, home/elsewhere, etc. I also appreciate the way you include the historical description of the tornado to link together all of your film examples and the work of The Bridge Club. I also had a discussion with my parents the other day about the many films and literature that focus on or are somehow driven by extreme summer heat as you mention in Picnic: The Great Gatsby, A Streetcar Named Desire, Do the Right Thing, etc. It is fascinating how driven we humans are by elemental forces.

Thanks for a great read!

Natalie

Fantastic piece, Melinda!

I am honored for the inclusion of my film.

I’m really keen on this idea of the “schism” that you mention, as experienced by Mary Henry in Carnival of Souls. The concept rhymes very well with the relationship between the light and dark sides of Kansas. There is this fracture between the iconic, idealistic paradigm of Americana that we so typically see in depictions of the Heartland’s past, and the underlying reality of life, which can be much grimmer and darker. As you alluded to, I touched on this dichotomy in Once in a Lullaby. Similar to Mary Henry’s doubling, the double image of Dorothy’s profile amidst the torment of the storm symbolizes her state of limbo – she is not quite there, in the present, but caught lingering somewhere between the dream world and the real.

I love the connection to the projected lightning storm as a curio to be observed which ties so neatly into the BridgeClub’s ongoing trailer project. Also the map as charting the vanishing of a place as the girls sanded out paths across the map, so good!

As someone who was born and grew up in “nowhere” Illinois, which is closely related to its Kansas twin these connections of home and the comfort of professed but unlikely terror are quite familiar. I remember fondly the bi-annual tornado drills throughout grade school. While staring out the window from the classroom onto the rows of cornfields we would be asked to walk out into the hallway in an orderly manor and quietly tuck into a ball in front of the concrete block hallway walls that were painted thickly with institutional blue, green and yellow paint that purported to keep us calm and focused on our studies. We were ordered to silently remain with our hands over our heads and our heads towards the wall, which left our asses hanging out into the hallway, and wait for instructions. While listening to the tapping of the teachers shoes walking down the hallway I would always imagine a tornado ripping the classrooms away and leaving the vertebrae-like hallway undamaged and the shame of not being able to see it as we had to keep our heads down.

This is an incredibly fond memory of mine that i revisit from time to time. I feel that growing up in a place that is so safe from predators and almost all other natural disasters that it was essential to keep this fear alive as a way to have a relatively safe relationship with destruction and death. Growing up in the 80s the only other possible fear was that russia would parachute down and take over the school as “Red Dawn” had proposed to my young mind. These fears were part of everyday play growing up, tea parties were not for me but rather survival games ruled the backyards of me and my friends.

I still imagine threats in my adult life although now they are diseases or other hypochondriac fantasies. It is an entertaining defense mechanism against real fears of course and perhaps is why a place like kansas has plenty of satan fearing advertising going on. Another excellent choice for a fear that comes from the outside and is extremely unlikely to affect your day to day but rather waits for when you have some time to whirl it into a frenzy.

This essay really brings home (pun completely intended) this idea that the safety of home needs an aestheticized threat of destruction to heighten the power of its protection. We must have access to both comfort and fear or the other is meaningless or at least boring. I have always thought that this is one of arts main functions and this essay for better or worse has further cemented that into my mind.

Thanks for a great read.

Matt

Melinda,

I loved this swirl of images.

It does seems to be a trope of good Americana that things looks smooth, normal and even homely on the surface and all the while something more complex, dark and lurid lurks below. The native Kansas plant called ninebark has roots that can grow 16 feet long. It is a simple shrub, little white flowers, extraordinary only in its tenacity…. and what is not seen. Not unlike the obscurity of night, what is under Kim Novak’s dress or the famous prairie storm clouds that threaten to wash away all that grid-like order of agriculture and religion that keep the roofs tied down. Normalcy begets it’s opposite- sometimes just tawdry, sometimes dangerous- always the leveling of the scale. Be it the aching desire that hangs on the edges of housewives doilies or the sinister crimes in Cold Blood, it cannot be erased – only hidden or dressed up to go to town. Kansas seems to be synonymous with this kind of oxymoron. All things invisible need form to show that they don’t exist and vice versa. The final image of your family, no faces visible- just gestures. A nod to unity and complexity. Love, loss and other things just out of view, that we long to touch, but cannot. A haunting meditation on home and the difficulty of finding it.

Thank you again for such a thought provoking article that illuminates both the world of film and your own past, as we have discussed movies are the primary lens through which I view my past so I’m right there with you. Something that always cracks my friends up is that I know when events happened by what movie came out that week/year rather than by date, for example I know I graduated from high school the weekend before the second Austin Powers came out, which following a quick Google search means I graduated the first week of June 1999.

Beyond semi-goofy anecdotes I’m drawn as I always am to the links between dreams and movies. From Dream of a Rarebit Fiend through Inception and beyond the links between the movies and dreams are far to plentiful to go into here. However a connection I had never made until reading your article is that the main time frame when people think of going to the movies is at night. The 7:00 show times are called the “Prime Set” by those in the movie theater industry. More than that I always tend to think of film people as being night people. With this in mind I’m now wondering if this ties back into the realm of dreaming and seeing movies as visiting a dream. Do we watch movies primarily at night as a way to dream? What about those of us who spend the vast majority of our time watching and analyzing movies, do we live in a state of waking dreams? And when dreams become your everyday reality are we like Dorothy in Once in a Lullaby in a constant state of dreaming? If so does that mean that our conflict is less with the dreams than it is with when the “real world” encroaches on our dreams? I’m sorry for the series of almost free-association questions but I think your article opens us up on to what we delineate as being home and safe which in my world generally means there is a movie (or eight) involved.

I completely agree that we need the night, and I think that is part of what draws audiences to the horror film, particularly those of the supernatural variety like Carnival of Souls. Night and the dark open our minds to how fragile we as human beings are, whether it is in the face of a supernatural or natural terror, and in this understanding we can use horror movies as a release of those fears by placing them into a self contained world of a movie where by the end of the film there is some manner of closure. One might argue that in the horror film we face our nightmares in order to be able to better enjoy our happy dreams. By the end of a horror film we have seen the darkest parts of the world and can leave back into the light. While it would be easy to take this idea into the realm of Plato’s Allegory of the Cave I will instead say thank you again for the article, cue up Wizard of Oz in my DVD player and end with a quote we are both fans of: “Leave the door open for the unknown, the door into the dark. That’s where the most important things come from, where you yourself came from, and where you will go” (Rebecca Solnit, from A Field Guide to Getting Lost).

Robby Mehls

BAMA Candidate

University of Colorado, Boulder

Dear Dr. Barlow,

You have once again written a beautiful piece that resonates deeply with me and my own experience.

The weather is omnipresent in the mind and life of former residents of Kansas, and tornado alley, and no doubt with the present ones. As every spring and summer day has the potential to change one’s life – and not for the better – the sky is always watched with a sense of apprehension, fear and foreboding. Any slight change to its color, stillness and weight can evoke feelings of anxiety that tornadic activity could change your peaceful existence in the blink of an eye. While driving in Illinois many years ago, my eight year old nephew looked at me and said “I don’t like that sky, there could be a tornado” everyone knows the signs, I remember saying to him “it will be alright” but, I too had been looking at it with apprehension thinking the exact same thing. Watching the weather became a daily activity, it didn’t matter that we had moved away from tornado alley. It was a mild obsession, but ever present. My grandfather would watch the weather all the time, listen to the radio and say things like “you can’t go there – there’s a tornado!” My own father watched the weather incessantly, a trait that I now possess and my sister do as well. The fearful beauty of the fateful sky. It doesn’t matter that we don’t live there anymore – it stays with us – the near and remote knowledge that your life can change on a dime. As you note, quite eloquently I might add, that “We pick up. Move on. Put down new roots. Leave again. Return once more. Feel the winds of change and try to read the signs as we become more attuned to the meteorology of memory.”

Thank you for writing such a lovely piece.

-Amy

“A telephone operator died at the switchboard.” A telephone line cut, gravity unbound as foundations are swallowed up in the vortex, both external and internal, and we are left, like Dorothy, wondering where we are, and how we got there. Barlow takes us through a Kansas more like Minor’s version of Oz than Fleming’s, a paradise with a hint of hell. This view of the juxtaposition of darkness and light reminds me of multiple instances within Nietzsche’s The Birth of Tragedy. First, in Raphael’s Transfiguration, the celestial Appollonian air-bound gods rely upon the grungy chaotic Dionysean foundation to stand upon as they mockingly float above.

Within the Kansas of Barlow’s work lies this darkness, of mass-murderers, drag race drivers, and sweeping storms. Nietzsche also remarks upon negative sunspots. “When we make a determined attempt to look directly at the sun and turn away blinded, we have dark-coloured specks in front of our eyes, like a remedy, as it were. Those illuminated illusory pictures of the Sophoclean hero, briefly put, the Apollonian mask, are the reverse of that, necessary creations of a glimpse into the inner terror of nature, bright spots, so to speak, to heal us from the horrifying night of the crippled gaze.”

In Barlow’s essay we are allowed to sink into the chaotic abyss and lie within the storm and embrace the sublime maelstrom of nature and the soul that we live within. Here, we are not allowed to bask in classic “serenity” but rather allowed to jump into the chasm of darkness, and flow within its superabundance, as dark surpasses anything that is not light. The ferocity of storms as they overtake the landscape with darkness can feel like a connection to a divine force, which reminds me of this short film documenting a supercell I saw in the last couple of months, as it went viral on the internet. (Please don’t listen to the god awful music within it). There is some security in having a transmitted medium between the viewer and storm, a sense of cgi that the atrocity is not one’s own.

I have always found watching storms incredibly entertaining. On the brink of puberty, my own physical storm, I sat on a porch in the Florida Keys with my father and watched a series thunderstorms hit the ocean with such ferocity that a waterspout came out of nowhere. Why is it we like to watch storms with such beauty but we fear their imminence? Just like Michael Shannon in Take Shelter we wait for the storm to overtake our soul, and no matter how much preparation we do there is no way to know what will hit until it lands.

Thank you Melinda for this thought-provoking article that has, Without Warning, brewed my own internal storm.

-Silas Rudel

Melinda,

This is a very interesting read! The thought of home is what stands out to me. I have lived in Boulder my whole life and it is definitely my home, yet it still feels not quite right. I believe people are never fully satisfied with “home” and are always looking for change- the grass is greener on the other side. In the beginning of The Wizard Of Oz, Dorothy wants nothing but to leave Kansas. Yet as soon as she finds herself in a new place, she wants to go back home. Kansas for her-just as Boulder is for me- will always be home. No matter where we move to- where we are from always sticks with us. Yet when we are home, we constantly want change, we want something new. Everyone in Salinson is infatuated with the new guy in town because of exactly that- he is new. He brings something different to the table- which is he knows more of the world. He is a drifter- he has tried new places constantly and thats something these girls in this small town want. Being with Hal may be the closest they ever get to leaving their small town.

Being from Boulder means that CU is usually a safe bet for college. Many of my friends (and me included) want to go out of state more than anything. Yet most the people who do end up going out of state transfer to CU a year later. In theory leaving home sounds amazing- but in reality it is much harder. There really is no place like home- where ever that may be.

Naomi Weingast

Potential BAMA Candidate

University of Colorado Boulder

Melinda,

What a beautiful and enlightening read!

Once in a Lullaby provides the perfect framework to expand from; it reveals the dark, nightmarish quality hidden beneath the ordinary, safe fairytale. By revealing the darkness beneath the light, the danger behind the calm, you bring us to our nightmares, our dreams, our uncertainty, you bring us to Kansas: a living example of a space in between, given to us in the form of dust and wind.

I now think of Kansas as a schism – a space in between, the essence of an elsewhere and the structure of a dream. The void, the tunnel, the nowhere, the place left behind. But Kansas isn’t just nowhere, it’s the middle of nowhere; violent, tumultuous but also plain and wholesome as you said. In film Kansas is used as the perfect setting for growth, for characters to explore their darker side, and eventually it is a place for leaving. It is a primordial home, one that is not a place but an elsewhere, a reflection of our own psyche; our struggles with the unknown self.

There’s no place like home, but what is home; is it even something that can be left behind? Or will it follow you like it did Dorothy, roots still clinging to clumps of soil, creating a twisted dreamscape where we must face ourselves in the I of the storm. I can’t help but think of an ego/id duality between Kansas’s wholesome surface and violent weather, which ties in perfectly to dreams and nightmares; the supposed gateways to our unconscious minds.

Before reading this I had two different Kansases existing in my mind: the all-American, wholesome Kansas, and the dangerous, violent tornado Kansas. Never did I think to merge the two, to see them as one and the same. This article has helped link up these two opposing ideas into a bizarro-Kansas that is both a fairytale and a nightmare rolled into one; a reflecting pool to ourselves, a placeless location that we have all left behind.

Thank you for a great read!

-Melanie

The Matter with Kansas.

Talk about Darkness on the Edge of Town. So very refreshing to read crisp, clean straightforward writing, nicely paced with key snaps as we scroll down, with choice words here and there adding poetic chiaroscuro to the evocatively descriptive causes and events and quietly surprising linkages —all emerging from the same Source, your Kansas and ours, with the ever-present sounds of the foreboding winds of the Main Event, circa ’55, blowing through the streets and plains of all these disparate yet twined towns without pity…

The best kind of essay writing welcomes us in real time, providing interesting and informative historical background details while still inspiring us to visit or revisit the works in question on our own, inviting us to take the case deeper and wider, to place all of these unlikely scenes into kind of an imaginary bas-relief map of the whole, methodically building the case for magical co-incidents and connections, as we rise up above the flats and plains of Kansas and and begin to see the larger view, that big picture window of the American dreamscape itself…

Love this kind of (wholly uncommercial) mashup that is not interested in its own cleverness, but rather in offering us a kind of GPS to imaginary places where the whole is cumulatively greater than than sum, and, yes, you can get there from here (follow the yellow brick road, click your heels, etc.). From the wild gales of Udall and Baum to Josh’s Minor keys and “smoldering” skies, over Annie’s Black Shift Bridge by way of Harvey’s doubled mirrors, Brooks’ window teardrops, and the shirtless (poor Bill) Holden, all flaring out at road’s end, the family aflame…

“Our souls and skins crave moonglow.”

Agreed.

Phil Solomon

Professor, Film Studies

CU Boulder

PS – re: Ghouls and boys.

I was reminded of seeing Carnival of Souls at a Saturday matinee and being absolutely terrified of those black and white abandoned amusement parks and the constant –threat–of haunted reflections…these childhood fears would eventually work their way into my own work, the riderless carousels of the night of Nocturne and Clepsydra, the yearly televised terrors of Oz eventually transmogrifying into my nightmarish Secret Garden. Your lovely and understated essay invoked all that and more…

PPS – The mention of Herk Harvey’s apprenticeship in 16mm industrials brings to mind the cine-roots of Mr. American Darkness himself, the late Robert Altman, and his 65 films made for the Calvin company…of Kansas.

I wonder if our fascination with dark and dangerous events, imposed upon the unwitting residents of an ‘innocent’ geography, relies upon our shared desire for the possibility of intercession? A tornado is pure potential, in this regard: potentially, we could be struck down or spared; potentially, we could see evidence of the universe’s impartiality or favor. The Bridge Club’s treatment of this subject in the work described here invokes an attempt to decipher clues laid out by the natural world, as if to ‘earn’ intercession by reading the metaphysical signs. This has been an element in several of our past works, as well— i.e., Medium, in which the performers seek arcane knowledge through patterns in sound and light. However, this essay gives heightened attention to the need for innocence— or its perception— in the population seeking divine or superstitious providence, and I anticipate that these ideas will inform our future works in potent ways! Thank you Melinda, once again, for offering us the benefit of your finely-tuned and expansive ideas. It is an honor to be included in the realm of your interests and analysis!

Julie Wills

http://www.juliewills.com

http://www.thebridgeclub.net

This is a great article to read! It is a piece where each example truly captures the duality of Kansas (conscious/unconscious, wholesome/darkness or voids, dreams/nightmares, etc!) Having too many associations to the state itself, I was particularly intrigued reading about Rushdie’s concept of Oz being Dorothy’s real home instead of her home in Kansas. After having written my thesis and viewing Kansas as home and Oz as her unconscious desires – it was refreshing eye opening to view Oz in a new light, especially in regards to Rushdie’s claims and Minor’s film. Thinking of Oz and this article on Kansas – I am reminded of a memory almost forgotten. When I was 6 or 7 – my family visited Liberal, KS where my aunt and uncle lived (My mom and her siblings were raised in Garden City and Wichita). We visited Dorothy’s House and Land of Oz museum/attraction. Included was a house that looked like Dorothy’s but there was also Oz and the yellow brick road. Of course the day we visited, the place was closed. We could walk the yellow brick road – but could not see Oz or the house. Although we were unable to enter – looking back – it is interesting to see that the world of Oz “exists” in the real land of KS. If Rushdie describes Oz as Dorothy’s home – then it is now in her home state of Kansas. It’s a weird association, but this article triggered this specific memory.

Along with Minor’s film – this article emphasizes the need for the night – especially in films based in Kansas. Where it is “wholesome and decent and ordinary” in both reality and films, Kansas is a place where the people are humble, religion is extremely prevalent, and the roads from state line to state line are flat. Having driven through KS multiple times – my sisters and I nicknamed the state Purgatory. It is a never-ending void – “nowhere”. The night is needed to dream, desire, and act and this has been well expressed in the films that Melinda has mentioned. This article also perfectly compliments our dualities as humans – day/night: conscious/unconscious. In a sense, we as unique individuals are Kansas.

Lastly, the concept of the uncontrollable nature and wonder of tornadoes is astounding. As tornadoes are an unpredictable destructive force, Melinda cleverly weaves the properties of a tornado in each and every example. Describing Mary Henry’s dream (?) world as “the center of the vortex…the I of storm who does not survive”, is particularly memorable.

As I could personally identify with many points in this article (+ with innumerable associations with Kansas itself) – there is a lot that I could refer too and comment on! However, I will refrain from doing so. As a comment can only say so much – take the time to read this article as it is telling, deep, and refreshing. This is yet another great article written by Melinda and it was a true pleasure to read! Thanks Melinda!

Kelli M Johnson

M.A. Candidate – Cinema Studies

University of Toronto

Thanks for this evocative essay.

To me, the plains of Kansas seem to blur into the plains of eastern Colorado. That’s in real life, not in the movies. The natural topography of the prairie makes these two states feel more than just geographically coterminous…do they also share a sensibility, an attitude, a sunny exterior concealing a gothic underbelly? KS and CO share a border, of course: one of those artificially drawn borders that characterize so many western states, a line drawn on a map rather than a division that follows any natural boundary. (I’ve never understood why they drew the western states as a bunch of arbitrary squares rather than using natural divisions such as the Rocky Mountains.) Most importantly, eastern CO and western KS share a landscape. In film, so many actual locations function as “stunt landscapes,” one place used to stand in for another. Terrence Malick’s BADLANDS was shot in Colorado, for example, though the story is set in South Dakota and Montana. I have always loved that THE WIZARD OF OZ uses a sound stage to conjure up the image of Kansas. Sound stages are the ultimate stunt locations. This article makes me think again about the relationship between landscape, location, and meaning.

Also, an aside: Kim Novak as Judy Barton in VERTIGO is from Salina, Kansas — another film about the “meteorology of memory,” what a resonant term that is.

I will definitely look for the Herk Harvey industrial film STAR 34, which sounds dismally boosterish (in the best possible way, of course). I see it’s on the Criterion DVD for CARNIVAL OF SOULS.

If and when people from other parts of Canada and elsewhere think of Alberta’s landscape they picture the Rocky Mountains and the picture-perfect town of Banff – the first National Park established in Canada. They may too think of Calgary the booming city with its oil companies. It was not until I moved here that it dawned on me that 80% of the province is prairie and the mountains form only a thin spine along the western border between Alberta and British Columbia. We are justifiably proud of them and the spectacular landscape that they represent but the mountain landscape really belongs to British Columbia. Our prairies, which back up first to the foothills and then the Rockies, make us one of the tornado capitals of Canada. I didn’t know that until recently. That they now advertise “tornado chasing tours” here is another new revelation. What I do know is that, like the people of Kansas and the rest of the Midwest, our eyes are often searching skyward, trying to interpret the weather and what is coming. A seemingly sunny clear calm day can in a moment turn ominously black and the sky can unleash its fury of rain, hail and tornados. The suddenness of it leaves us breathless and exposed with nowhere to run. We don’t hold storm drills nor do we have tornado cellars here. Perhaps we should. But we all feel that vulnerability when it comes. The performance of the Bridge Club mirrors our own.

Those days here remind me of the opening scene in the Wizard of Oz when the storm begins to swirl. It is a constant reminder that we do not control our world, at least not outside. And when that storm starts within, that emotion too cannot always be controlled. We are neither safe inside nor out and we cannot always comprehend or explain it. As the storm passes, everyone is anxious to reveal their photos, capturing it at its most intense – the light, the dark and the terror. The photos somehow provide proof we have survived this time and they somehow normalize the experience and neutralize our fear.

Melinda’s choice of film and performance pieces weaves a captivating story that captures this dichotomy between light and dark. Her writing inspires us to revisit the ways in which it invades our own lives and despite our best intention to live in the light, perhaps at our core we do need the night with its uncertainty and its anxiety and dreams in order to understand and appreciate that light.

I’m intrigued by the connection between the timing and location of the Udall tornado and the filming of Picnic. I recently directed the stage version, and we found tornadoes to be woven into the play’s Kansas landscape, though not explicitly. As I was working with the actor who played Hal in our production, I was reminded of a Neko Case song, “This Tornado Loves You,” in which a tornado lays waste to everything in its path just to get close to the one it loves. I never encountered a better metaphor for Hal, a young man with good intentions who consistently wreaks havoc everywhere he goes. It was only after I located that metaphor that I became aware of the significance of an early conversation in the play – the women are sitting outside on the porch, and the neighbor Mrs. Potts says she’d “welcome a good cyclone” in the late summer heat. She’s the first (possibly only?) to sincerely welcome Hal when he gets to town.

This article also brought to mind a recent performance piece a friend of mine created about being from Kansas. She regularly gets unoriginal jokes about ruby slippers, “you’re not in Kansas anymore!” and the like, but her piece was about growing up in the shadow of Fred Phelps and the Westboro Baptist church, and realizing after leaving home that in other places, hateful picketing is not the norm. Talk about conflicting cultural images of home.

A last point about Picnic in context of this article – every character in the play is introduced as a type. We have the pretty sister, the ugly/smart sister, the bad boy, the standup good guy, the spinster schoolteacher. And every character rejects that type internally and reveals so much more complexity throughout the course of the play. How appropriate that Picnic, a play about the contrast between surfaces and depth, is set in the romantic Kansas of Oz and the oppressive Kansas of Westboro. After Madge’s illicit night with Hal, some local boys drive by catcalling her about going out with them for a night. What else to call their jeers but slut shaming? The play brilliantly allows for that duality in its open ending. Viewers can decide whether Madge and Hal living happily together after, or if things go very badly for them. The ending, like the play, and like the state, can be romantic or oppressive. Probably a bit of both.

Heidi Schmidt

Ph.D. candidate

Department of Theatre & Dance

University of Colorado Boulder

I am attracted to Dr. Barlow’s choice of Kansas and films about Kansas as a space that can be invaded by darkness, madness, fantasy, and chaos, despite the land’s remoteness and protection of nostalgia. These films and stills, most of which are shot at night, suggest Kansas as one of the few remaining places where the subconscious has enough space and repression to emerge as churning force, of nature and human nature. Only under the sanctuary of dark can Dorothy dream, Hickock and Smith murder, or Hal and Madge make love.

It also appears that Dr. Barlow connects this theme of darkness with the inability to escape, as if Kansas on film has no roads under a starless sky. It is interesting that you use your own family photograph as the only image of Kansas with “its own strange rainbow.” Even if you are still dreaming about Kansas, you did in fact leave.

Kate Faulk

MA Candidate

Department of Art History

University of Wisconsin-Madison

Melinda,

a very poetic read! The films, literature and performance art (spanning the 1930s up to the present) beautifully weave together a haunting depiction of Kansas. On one hand you have the heartland, a place stable and strong (where Dorothy returns, where towns are rebuilt after tornadoes, where good ordinary people like the Clutters live), but on the other, it is a place that can instantly turn on that perceived wholesomeness (the Clutters – gone, Udall – gone, The Bridge Club’s storm tracking — chalk lines / atlas lines disappear, Dorothy swept away, a drifter unsettles a town)

But what I especially love is how you take it further and express how we all need this night, this necessary darkness , dreaming anxiety to set us straight. It causes us to rethink, rebuild, uproot, move on. Although there is an inherint, underlying darkness — we need this and there is beauty here too. I loved the ending with the “rainbow” over your family photo

Thanks for such a wonderful article — Carnival of Souls and Picnic are two films I need to see again!

Jen Dean

Film Editor

Arcade Edit

Melinda,

Great opening! It puts me in the middle of a time I can’t quite imagine. You bring all these pieces together so well, and have managed to weave a story of variegated character but connected by a consistent thread. As a Rushdie fan, I loved that this helped form the backbone of your piece.

The theme of leaving is a compelling one – one that transcends these particular arts and touches all parts of human experience. As a student of civil conflict and terrorism and their impact on civilians, leaving, and why we leave, are among the most powerful narratives I find in my own research. I particularly liked your closing – the power of night and shadows contrasted with those bright and dark images – and the idea that leaving and change in fact hold us together.

Emily Gade

Richard B Wesley Fellow in International Security

PhD Candidate, University of Washington, Department of Political Science

MSc London School of Economics

Hi Melinda!

Coming from the woods, tornados are like a myth. I’ve seen the first signs of 2 in my whole life for the first time a few weeks ago, and despite the AT&T warnings and dark skies, I haven’t gotten close to feeling some kind of impending doom.

This anxiety of impending doom that can be felt in “Picnic” and “Carnival of Souls” and the way you identified it reminded me of my favorite concepts from R. Barthes in his “Discourse of Love”; for a few pages he mentions a state of mind which he pin-points as “Estar a Oscura”, the idea that one can never ever understand their partner, one will always dwell in the darkness of their mysterious, ever-evolving being. Estar a oscura is a meditative state of everlasting darkness.

Now, “Estoy in Tinieblas” resonates more with the tornado; as the situation is similar; one realizes that their partner will never be fully known, however, the modus operandi is different. This concept isn’t a state of mind, as “estoy” means “I am”, it’s a realization of one embodying the anxiety, or being possessed by the anxiety of not knowing one’s partner.

This push and pull between Estar and Estoy is an eternal struggle and we, as human being center ourselves too deep into either or situation, and often forget to take a step back and forward, to understand that we need darkness to grow, and we need oasis of light to move on.

As you said:

“We need the night. We need its obscurity, ambiguity, and shadow-filled beauty. Our souls and skins crave moon glow. We also need the night’s uncertainty, perhaps even its anxiety, and we always need to dream.”

Perfect! <3

-Maya

Hi Melinda!

Coming from the woods, tornados are like a myth. I’ve seen the first signs of 2 in my whole life for the first time a few weeks ago, and despite the AT&T warnings and dark skies, I haven’t gotten close to feeling some kind of impending doom.

This anxiety of impending doom that can be felt in “Picnic” and “Carnival of Souls” and the way you identified it reminded me of my favorite concepts from R. Barthes in his “Discourse of Love”; for a few pages he mentions a state of mind which he pin-points as “Estar a Oscura”, the idea that one can never ever understand their partner, one will always dwell in the darkness of their mysterious, ever-evolving being. Estar a oscura is a meditative state of everlasting darkness.

Now, “Estoy in Tinieblas” resonates more with the tornado; as the situation is similar; one realizes that their partner will never be fully known, however, the modus operandi is different. This concept isn’t a state of mind, as “estoy” means “I am”, it’s a realization of one embodying the anxiety, or being possessed by the anxiety of not knowing one’s partner.

This push and pull between Estar and Estoy is an eternal struggle and we, as human being center ourselves too deep into either or situation, and often forget to take a step back and forward, to understand that we need darkness to grow, and we need oasis of light to move on.

As you said:

“We need the night. We need its obscurity, ambiguity, and shadow-filled beauty. Our souls and skins crave moon glow. We also need the night’s uncertainty, perhaps even its anxiety, and we always need to dream.”

Perfect! <3

-Maya

Professor Barlow,

This essay and its structure intrigues me. I reached the end, in which you explain how “We need the night,” and I was initially confused, in part because I felt some personal resistance to the idea. I’ve never been one for ‘night,’ I thought – sleep annoys me, I only ever have bad dreams, etc. But then I went back and re-read the essay, re-analyzing all your examples with knowledge of your ultimate conclusion, and I had an entirely different takeaway, understanding how my initial reaction – “How can we need the night?” – is part of your overall argument, about the dichotomy of night’s horrors and night’s possibility. Reality, as you explain, is harsh. Rough. Unpredictable. We culturally value the ‘day’ as the bastion of ‘reality,’ the world in which we are meant to exist, but there’s no reason a tornado cannot strike in broad daylight, in our waking and alert hours. And if all of reality is harsh, at least the night, with its many unknowable qualities, has a certain freeing possibility to offer us. That possibility can be bad or good – the murders of In Cold Blood are only tragic and confusing, of course – but either way, it is in those hours we might get a better sense of ourselves, our inhibitions, and our desires. Dreams do this, of course, but simply being awake at night, feeling a little more disconnected from the world when there is no light, can also shine some enlightenment upon us. I always try to overcome this by writing during the day, but it rarely fails that I do my best writing when it’s dark outside, when I should probably be sleeping, when there’s nothing else out there to capture my attention. You mention the night’s anxiety – indeed, there is a certain anxiety to being awake at night, and perhaps that fuels my ability to write during those hours, or anyone’s ability to see themselves and their ideas more fully at night. The anxiety is propellant.

This is a complex piece – I am still grappling with its ideas, and shall continue to do so, but after two readings, I find it quite thought-provoking.

Jonathan R. Lack

BAMA Candidate

University of Colorado at Boulder

Thanks so much for the inclusion of The Bridge Club’s work in both this and your essay When Sleepers Wake and Yet Still Dream. Your thoughtful analysis of our work and the works of others are so poignant and woven together in such a poetic and effortless manner.

I packed up a U-haul in 2009 and drove down 70 E to Wichita KS where I lived for 3 years while in a visiting artist position at Wichita State University. It was on that drive that I saw my first tornado- what I described as a giant ice cream cone in the sky hovering over the Colby, KS exit. I couldn’t believe I had barely arrived in KS and there was this legendary threat right in my path.

This was no doubt a warning sign for me, a sign that my life would be picked up and turned upside down and changed by my experience in what seemed like a very strange new place. When I first arrived I, like Dorothy just wanted to go home –I thought I had landed in the wrong place. At first it appeared so void of inspiration but over time I found that this “nowhere,” “that great void” held a great and long lasting fascination for me. The Kansas landscape and its’ treacherous storms made me acutely aware of my own internal landscape, my own storms and rainbows. It is truly a place of contrasts as you so eloquently described and in it’s vast landscapes and skies a place where so many things can be revealed. Your essay provides so many wonderful connections, insights and references, I am so thankful that you are interested in our work and I am so grateful for your writing.

Thank you!

Annie Strader

Assistant Professor

Department of Art

Sam Houston State University

http://www.anniestrader.com

http://www.thebridgeclub.net

Melinda,

Reading this essay, I’m fixating on fractures. The wholesome stereotype of Kansas torn up by the darkness and turmoil of a tornado. The fear and uncertainty of nighttime soothed by our need to dream in the moonglow. The anguish of existential crisis (Mary Henry in Carnival of Souls) experienced within the privilege of living, a privilege lost by those tornado victims. The schism between father and daughter, mother and son, as your family photograph fades into the picturesque glow of a rainbow. These contrasts compliment; fracture creates beautiful nuance.

I think that there is a beauty to be found in sadness, darkness, and trauma — or at least, I look for it as a comfort within my own life. I experience it in your writing.

Megan Gafford

MFA Candidate, Painting and Drawing

University of Colorado at Boulder

Pingback: Antiqued Blog