What Facebook’s Emotion Experiment Tells Us About What We Think About Feelings

Jennifer Petersen / University of Virginia

The news of Facebook’s “emotion contagion” story made its way around the web last month. The company had, in 2012, changed the algorithms governing the newsfeeds of close to 700,000 users, to either favor positive posts or negative ones. The results, published at the end of June, suggested that positive posts from Facebook friends beget positive posts, and vice-versa – or that these moods were transmitted via the social network. The journalistic, if not public, response was of outrage at the invasion, ethics, and untoward manipulation of the study. The Washington Post asked “Was the Facebook Emotion Experiment Unethical?” More alarmed, The New York Times said that the company viewed users as lab rats in “Facebook Tinkers With Users Emotions in News Feed Experiment, Stirring Outcry.” The Guardian said Facebook wanted to control users feelings. Other major news outlets reported on the “criticism” even “furor” of users after study’s publication.

The media brouhaha has largely died down, but it’s still worth taking a minute to consider why so many people got so upset. The study caused more controversy than the earlier experiment aimed at affecting voting behavior.

Certainly, Facebook’s experiment violated informed consent guidelines. It also showcased the company’s use of personal, social communication for its own ends (and, at least according to Vice media, potentially Pentagon interests in predicting civil disorder). These are excellent topics for public discussion and criticism and in fact showcase many of the more everyday and ubiquitous problems of the terms and conditions imposed by the company. Yet, it was the fact that Facebook was monkeying with users’ posts and feelings that was singled out as creepy. But isn’t tinkering with our posts and feelings what Facebook does? It is a “service” that actively and aggressively structures users’ social interactions, from the range of choices supplied by the interface for how to express and present yourself to the sorting algorithms that determine whose posts you get when. On one level, I understand the confusion expressed by the Facebook data engineers. This experiment was par for the course. Facebook regularly manipulates its algorithms without user consent to try to get people to use the site, and interact with each other, in the way that Zuckerberg et al. think we should. So why all the fuss over this one?

I suspect one reason is because this experiment too obviously manipulated users’ emotions. The deliberate selection of posts according to emotional tenor was for many, too invasive. Facebook might invade our privacy, mine our conversations to create user profiles, and “share” this information with advertisers, manipulate the newsfeed to encourage particular types of user behavior on the site, but filtering the feed by feeling went too far. This was personal. This reaction has to do with the particular baggage of emotions in American and Western European thought, their ties to subjectivity and private interiority. We have a long history of thinking about emotions as private, internal, specific to our individual, unique selves. They are what make us “us” in many ways. They are our innermost secrets. What make us tick. In popular parlance, emotional discourse descends into particularity and personal interests, whereas reason is universal, and can help us transcend particularity.

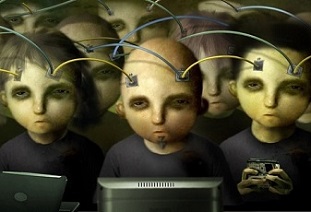

From this view, Facebook’s experiment is a deep intrusion into the innermost recesses of users’ selves. What is creepy about the experiment may be less that the Facebook algorithm manipulated what users saw and read based on the emotional tenor of posts, and more that this manipulation seems to have had an effect. It is that the Facebook algorithm got inside users hearts and minds to affect the moods evinced in users’ posts. If these moods are part of users’ most inner, authentic selves, these selves had just been invaded, or hacked, by a soulless algorithm. The revelation of the experiment and its results, in suggesting that emotions were so easily affected, hinted at a radical loss of self-control and autonomy – not just to other human beings, but to machines.

The sets of oppositions and alignments on which these fears rest are, as hinted at above, historically contingent. We have not always associated emotions with interiority and individual subjectivity. Passions and sentiments were once part of our political vocabulary, expected as part of public discourse. Peter Searns argues that sentiments became domesticated, associated with women and the home, in the late 19th and early 20th century.1 Others locate attempts to tame and suppress emotions within civic discourse to rhetorical and economic shifts in the 17th and 18th centuries.2 Our feelings about our feelings are the product of history and economy as much as personal history or individual psychology.

This understanding of emotions as the product of culture, history, and economy is becoming increasingly popular in fields including cultural studies, history, philosophy, psychology, and neuroscience. This research tells us that feelings are, in part, social or shared. The particular shape, intensity and expression of our feelings are defined by the emotional norms of the day—in other words, by discourse. Emotions do not so much well up from within as leak through porous borders between the individual and his or her social and material contexts. Interestingly enough, this was also the point of the Facebook experiment.

If we step back and consider emotions as social artifacts more than manifestations of our unique histories and psychologies, then the Facebook experiment is no more or less creepy than its everyday data manipulations and experiments. In fact, this experiment was by some metrics, less disturbing. Most of what Facebook does with users’ communication on and through the site instrumentalizes what users experience as interpersonal interaction, trust, intimacy, and personal identity formation into material gain for the corporation.3 The emotions experiment did not aim to capitalize on posts in this way, at least not immediately (though I would not be surprised if the results are used toward some such end).

Perhaps what disturbed in the experiment was not so much the manipulation, but the reminder that our feelings are not completely ours. Because, if they are not ours, who or what are we? Many of the hallmarks of personhood we learn through liberal individualism hinge on autonomy and mastery (or ownership) of our selves. If our feelings and moods are carried by social tides, then we seem less like liberal individuals and more like members of a hive. This need not be a bad thing, as pointed out by scholars such as Dominic Pettman,4 but rather can be an opportunity for re-thinking the subject, ethics and responsibility.

Image Credits:

1. Facebook Status Updates List

2. The Fear of Emotional Contagion

3. Dystopian Vision of the Internet Hive Mind

Please feel free to comment.

- Searns, Peter, American Cool: Constructing A Twentieth-Century Emotional Style (New York: NYU Press, 1994). In the 19th century, Searns argues passion and argument were tightly linked. Indeed, sentiments were encoded as part of manly discourse on matters of public concern within many guarantees of free speech written into U.S. state constitutions in the 19th century. [↩]

- Gross, Daniel, The Secret History of Emotions: From Aristotle’s Rhetoric to Modern Brain Science (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007); Hirschmann, Albert, The Passions and the Interests (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997) [↩]

- Not to mention the fact that Facebook is literally profiting from the trust and social bonds constructed in everyday interactions both offline and on, which are then transferred into Facebook networks and interactions. [↩]

- Pettman, Dominic, Human Error: Species-Being and Media Machines (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2011). This is a wide-ranging literature. Parikka, Jussi, Insect Media: an Archaeology of Animals and Technology (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010); Bennett, Jane, Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2010) are a few of the works thinking through the normative implications of distributed agency and other provocations of actor-network theory. [↩]