Who’s To Say? Why Television Criticism Is Complicated

Denise Bielby / University of California, Santa Barbara

When the door opened for anyone with an opinion about a television show to post it on the internet, like-minded viewers were better able to close the door on divergent opinions, while for others it offered an avalanche of insights that broadened viewing perspectives. But this landscape of abundant opinion also brought spoilers that ruined the reason to watch a series, details about production drama that overshadowed the show’s narrative, and idiosyncratic recommendations that led to wasted investments of time and money. In short, the internet was not always the most reliable, or beneficial, source for viewing recommendations.

Much has been said about how self-appointed critics have jeopardized the role, value, employment, and influence of professional critics. But professional critics are still around, and they remain influential. Understanding the reasons for their continued presence and ongoing importance can be addressed in two key ways: why, and how. Why reviews matter is important (see, for example, Bourdieu, 1984), but to more fully understand why they matter, how they come to matter, that is, the mechanisms through which they are able to achieve influence, warrants focused consideration. What practices do reviewers use to make their assessments effective? Despite considerable interest in why we watch what we

watch, the scholarship on how reviews matter, and how that is connected to the why, is fairly limited. The two media industries that most often come to mind when we think of criticism are film and television. The traditional separation between these two industries, which is becoming increasingly blurred as creative workers leave behind the formulaic plots and excessive commercialism of Hollywood to seek the ever-growing creative freedom of the subscriber-driven television industry, do still need to be regarded as somewhat distinct when it comes to criticism, given the different defining characteristics of each medium. Film, excluding sequels, is a multi-hour self-contained narrative, while television is a serialized form that can run from weeks to years, or, in the case of soaps, decades. What, exactly, should one review? The film industry is twice as old as television, and it has an established canon, an intellectualized discourse, organizations that confer awards to consecrate its products, crafts, and members, and an established field in academia.1 Perhaps most importantly, despite film’s obvious commercial imperative, for all these reasons it has come to be regarded as art, for which there is a valued place for critical judgment. Television, in contrast, is not, yet anyway, regarded as art, although it has certainly has become recognizably “artier” since the mid-1980s’ emergence of niche networks on cable. As the product of advertisers who in the industry’s earliest days owned the shows they aired, television missed the opportunity to establish itself as art despite its early potential to do so because of its imperative to reach the largest possible audience through content that would achieve widespread acceptance and popularity necessary for commercial success, and through its minimization of more controversial subject matter that made its consumption in family settings problematic. Television’s shorter history, its ubiquity as a medium that is regarded as mundane because of its embeddedness in everyday life, and its presumed lack of creative content, among other things, has made the medium of television an ongoing work in progress, and its appraisal a more complicated and underappreciated task. In short, until The Sopranos, it was a challenge to “appreciate” television as a creative medium and art form in its own right.

The practice of television criticism – how criticism comes to matter – has always been a complicated endeavor. One reason is that television is a cultural product with attributes that are a mixture of aesthetic properties and popular or commercial ones. This makes finding the balance between the art of television and the worthiness of its entertainment value a complicated task. Another is that the professional television critic has always occupied an over-determined structural location. Most reviewers of television programming, then as well as now, write for mass circulation newspapers

and magazines, so there are few specialized venues for critics to reach aficionados of the medium. As a result, criticism tends to focus on “Will the viewer like the program?” rather than the “public conscience” approach of elite publications written from the perspective of “Should the viewer like a program?” 2 A third is that most television programs still air on advertiser-supported networks that follow social trends rather than lead with creative content or themes that might alienate advertisers and consumers of their products. A fourth is that there is little opportunity for television critics to write about undiscovered or promising new creators whose work is breaking new ground. Because of the economics of the industry, new ideas do not get produced until they have been evaluated by the business interests who screen out proposed series that appear not to be commercially viable.

The emergence of artier television in the mid-1980s, initially on the narrowcast “weblets” (Fox, UPN, WB) and the niche-market subscriber-supported cable networks (e.g., HBO, Showtime) that brought an end to the era of the three major television networks, and more recently by video-on-demand services (e.g., Netflix), has freed television from these commercial constraints and has heightened audience interest in criticism that recognizes and appraises the qualities of television’s artier potential. But has television criticism evolved to reflect this? Blank states that reviews in general address two very basic questions: “What is it?” and “Is it any good?”, and that there are two basic types of reviews: connoisseurial, for such elite arts as theater, opera, or ballet, which are typically authored and draw on the unique and refined talent of reviewers, and procedural, for commercial products such as cars, appliances, or computer software, which rely on ratings/rankings groups of products and are comparatively un-authored or impersonal.3 These two types of reviews, Blank argues, follow different logics, focus on different kinds of texts, are created by different organizations, and are read differently by audiences. But television requires a mixture both types of reviews, and as Baumann revealed in his case study of film, when critics intellectualize their discourse, a cultural product can shift from “entertainment” to “art,” as happened to film.4

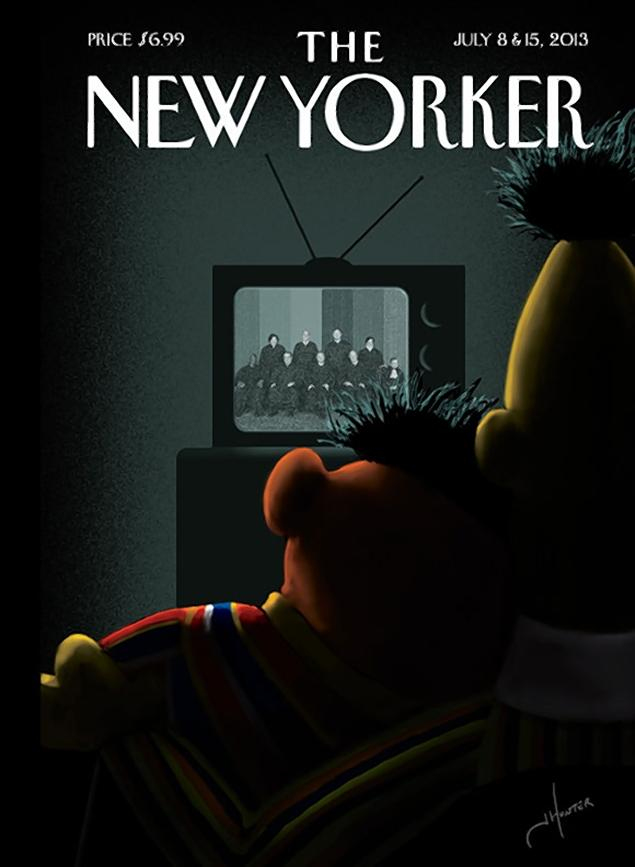

In a study of television criticism from the mid-1980s through 2000 that corresponded to the onset of the industry transformation described above, my research team and I found that television critics did, indeed, increasingly attend to the properties of television as an art form while they simultaneously retained a more traditional consideration of aspects such as entertainment value that are of interest to audiences and business constituencies alike.5 What did this shift in focus look like? First, we found that television critics explicitly attended with growing frequency to the emerging artistic/filmic aesthetic elements of television, and they did so within the context of specific genres (drama, sitcoms), thus distinguishing among different types of entertainment; this enunciated distinct expectations among established forms of programming. Second, critics offered opinion about the accomplishment or failure of those elements within the context of specific genres. In short, television critics had reason to emphasize a more connoisseurial voice through sensitivity to the nuance and complexity of television’s narratives, writing, and characterization. This shift in focus has, in turn, conferred increased status to the medium of television and its audience, which we now see reflected in disparate outlets such as the Los Angeles Times (whose lead television critic is Mary McNamara), which has historically emphasized industry-oriented coverage, the upmarket New York Times (and its critic Dave Itzkoff), which has evolved into one of a handful of elite newspapers in the U.S. with a national and international reach and impact, and the elite periodical The New Yorker (and its critic Emily Nussbaum), which focuses exclusively on artier cable shows, series with cult followings, and the cultural impact of television and the evolution of its audience. But what makes these critics – or any critic for that matter – influential? According to Blank the character (i.e., professionalism) and competence (i.e., knowledge and insight) of critics is key to readers’ judgments of reviewer credibility, in short, a critic’s unique skills, sensitivity, training, and experience matter.6 Blank argues further that credibility is not anchored just in persuasive rhetoric, but also in a critic’s authoritativeness – do they know what they are talking about (i.e., are they reliable), and are they truthful and on the listeners’ side (i.e., their character)? These attributes are established through consistency over time in the quality of a critic’s evaluations and the credibility of the organizational context in which their criticism is produced. In our socially diverse society this is often challenged by whether a review reflects the interests of particular groups. But this last point brings us back to the benefits and perils of the internet. While there is no shortage of particular critics who can speak to groups with particular interests, the internet-of-personal-opinion often lacks a credible organizational context. Unless one is committed to a long term commitment to building a trusted relationship, professional television critics not only have a future, they also have a rich one for scholars to explore.

Postscript: We note the passing of an era with the closing down of two venerable digital properties in April: Daily Candy and Television Without Pity.

Image Credits:

1. T.V. Criticism

2. The Sopranos

3. TV Guide

4. House of Cards

5. The New Yorker

6. Television Without Pity

Please feel free to comment.

- Baumann, S. 2001. Intellectualization and art world development: Film in the United States. American Sociological Review, 66: 404-426. [↩]

- Lang, K. 1958. Mass, class, and the reviewer. Social Problems, 6: 11-21. 15. [↩]

- Blank, G. 2007. Critics, Ratings, and Society. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. 7. [↩]

- Baumann, S. 2001. Intellectualization and art world development: Film in the United States. American Sociological Review, 66: 404-426. [↩]

- Bielby, D., M. Moloney, and B. Ngo. 2005. Aesthetics of television criticism: Mapping critics’ reviews in an era of industry transformation. In Candace Jones and Patricia Thornton (eds.), Research in the Sociology of Organizations: Transformation in Cultural Industries. Greenwich, CT and London, England: Elsevier. [↩]

- Blank, G. 2007. Critics, Ratings, and Society. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. [↩]

I was the Tv critic for the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, syndicated 3x a week first by Scripps Howard, later by Knight Ridder, from 1995-2008, when the job disappeared. I never met or talked to Denise Bielby, but I found this paper shrewd, nuanced, perceptive and refreshingly free of academic jargon. Yay!