Media Infrastructures and Affect

Lisa Parks/ University of California at Santa Barbara

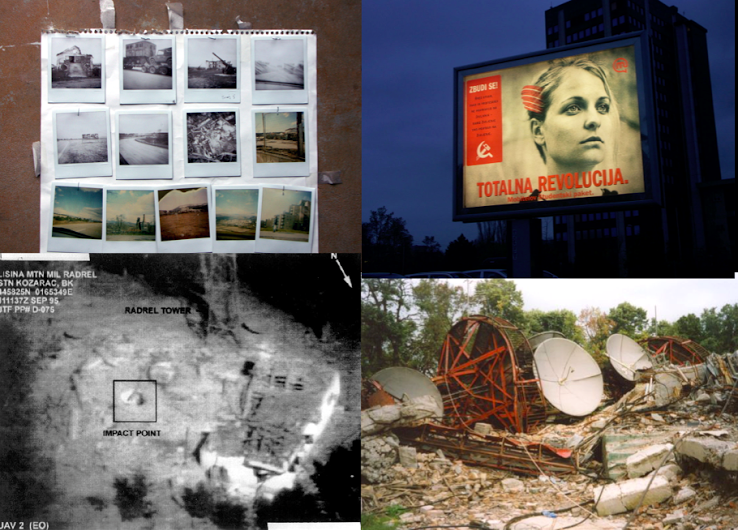

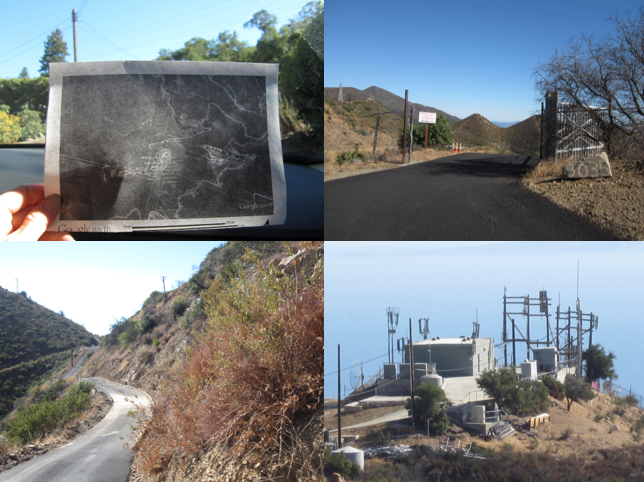

Some of my recent research1 has combined phenomenological and ethnographically-inspired approaches to explore the physical sites, objects and discourses that shape what might be called infrastructural imaginaries—different ways of thinking about what infrastructures are, where they are located, who controls them, and what they do. By exploring such topics as the destruction of telecommunication and broadcast systems during the war in the former Yugoslavia (Figure 1), the reinvention of mobile telephone systems by walking phone workers in Mongolia (Figure 2), and the lifeworlds around cable endings and transmission towers in California (Figure 3), I have tried to develop a critical methodology for analyzing specific infrastructural sites and objects in relation to surrounding environmental, socio-economic, and geopolitical conditions.2 This methodology has involved site visits and physical investigations of infrastructure using personal observation, photography, maps, video, art, drawings, and other visualizations. These observations and mediations are intended to foster infrastructural intelligibility by breaking infrastructures down into discrete parts and framing them as objects of curiosity, power, investigation, and concern.3

In his article on the politics and poetics of infrastructure, Brian Larkin foregrounds the many ways infrastructure has been thought about and studied in the field of anthropology, noting “the sheer diversity of ways to conceive of and analyze infrastructures that cumulatively point to the productive instability of the basic unit of research.”4 In the spirit of extending the “productive instability” of infrastructure and situating it within media studies, I want to sketch out a continuum for thinking about infrastructure and affect that brings phenomenological and political autonomist approaches into dialogue, marking them as distinct yet equally important and ultimately related to one another. My general argument is that there is a need, on the one hand, for a broader imagining of infrastructural affects—experiences, sensations, structures of feeling—generated through peoples’ material encounters with media infrastructures (not just interfaces but physical sites, installations, facilities, hardware), while, on the other hand, there is a need for an ongoing critique of the ways in which affect continues to serve as part of the base of media infrastructural operations.

Building on phenomenological writings, Melissa Gregg and Gregory Siegworth describe affect as “a gradient of bodily capacity-a supple incrementalism of ever-modulating force-relations—that rises and falls not only along various rhythms and modalities of encounter but also through the troughs and sieves of sensation and sensibility….”5 Infrastructures become part of such “force-relations” as peoples’ encounters with them in everyday life generates different experiences, rhythms, moods, and sensations. For many people, the default disposition to infrastructure might be indifference, apathy, or disinterest, but it is also possible that a broad spectrum of infrastructural affects remains unspoken and unknown, simply because certain kinds of questions have not been asked.

As a way of thinking through the possibility of extending infrastructural imaginaries, I want to briefly discuss Darin Barney’s ethnographic study of “grain-handling technologies” and “railway branchlines” on the Canadian prairies. Immersing himself in the life worlds of small-town grain farmers, Barney describes grain silos and railroads as places of focused attention and exchange in rural communities.6 One of his informants describes the grain elevator at Fairlight, Saskatchewan as “a place to hear the news—news of births and deaths and war and peace. It’s been a place to debate politics, wheat prices, wheat boards and hockey; a place to shake the loneliness of life on the land.”7 The take over of these facilities by big agribusiness during the past two decades, Barney explains, not only resulted in the gradual demolition and replacement of these infrastructure sites with more “efficient” farming equipment, but also generated feelings of isolation and frustration as farmers sat in long lines alone in their trucks waiting to unload grain in conglomerates’ new “through-put terminals.” By shedding light on “the complex ways in which infrastructural technologies mediate the organization of social and political life,” Barney’s research brings affective dimensions of infrastructures to the surface, while bringing different objects and actants into the repertoire of media studies.8

A phenomenology of infrastructure and affect might begin by excavating the various dispositions, feelings, moods, or sensations people experience during encounters with infrastructure sites, facilities or processes. Such an imaginary might begin with a continuum that recognizes, on one end, the general tendency of infrastructures to normalize behavior (such that they become relatively invisible and unnoticed), and, on the other, as the potential for disruption of that normalization, which occurs during instances of inaccessibility, breakdown, replacement, or reinvention. By sketching out this continuum, I hope to build upon Wendy Chun’s crucial work on networks of control and freedom and to suggest that an array of interesting infrastructural affects lay in the gray zone between them.9 The intention of this critical move, then, is not to reduce affect or turn it into a list of discernable emotions, but rather to catalyze further thinking about the range of ways people perceive and experience infrastructures in everyday life and how these experiences differentially orient or position people in the world.

In addition to this phenomenological approach, I want to briefly touch on the relationship between media infrastructures and affective labor, a concept derived from critiques of late capitalism’s shift from purely industrial labor to “invisible” or “immaterial” forms of labor involving various social skills, services, and modes of care.10 As Brian Massumi puts it, “affect is a real condition, an intrinsic variable of the late capitalist system, as infrastructural as a factory.”11 The case already has been made that network infrastructures rely upon the affective or immaterial labor of users in order to function and sustain themselves over time. Tiziana Terranova reveals that the Internet is not only a technical system; it operates by virtue of the time, energy, and attention of the scattered collectives of people who use it.12 Building on Terranova’s work, I argue that the use of immaterial labor to sustain media infrastructures is an historical and pre-digital process that dates back at least to the emergence of telegraphy in the mid 19th century. What we have in the current historical conjuncture is a compounding and intensifying demand for immaterial labor as industrial societies have undergone a shift from only one telecommunication infrastructure – telegraphy – to a post-industrial order in which multiple media infrastructures – telephony, radio, television, cable, satellite, Internet, and mobile telephony – co-operate and compete for user time, attention and energy. Landline telephony has fewer users today than it did one decade ago not because the system no longer technically functions, but because most people simply do not have enough time, attention and money to use their landlines and their mobile phones. Satellite radio networks shower hundreds of niche signals into continental footprints, but listeners do not have enough time to hear them all. Since most listen to satellite radio while driving, users would have to drive around perpetually for the rest of their lives in order to try and hear all content streams and still probably would never get through them all.

Such a scenario is suggestive of the compounding affective demands that have become part of media infrastructures’ current conditions of operation. The capacity to produce and distribute networked data not only creates what Marc Andrejevic describes as “infoglut”; these conditions, he suggests, turn affect into “an exploitable resource” that becomes “part of the ‘infrastructure.’”13 Andrejevic builds upon Daniel Smith’s assertion that affects “are not your own, so to speak. They are…part of the capitalist infrastructure…”14 Within such conditions, media infrastructures once thought of as public utilities have been re-organized as utility publics –-that is to say, infrastructures not only deliver utilities to publics but, in the process, re-utilize publics as part of the base of their operations. To concretize this, consider how much of your daily time and attention is consumed by computer interfaces, TV screens, ATM transactions, mobile phone calls, text messages, radio stations, GPS-based services. Then add to this, activities such as upgrading software, charging batteries, backing up data, synchronizing devices, and fixing equipment when it fails, and on.

With multiple competing media infrastructures in the marketplace, it remains to be determined whether there is enough human bandwidth to sustain them all, as well as figuring out what sustaining them means. As recent research by both Sarah Sharma and Jonathan Crary has emphasized, human time, attention, and energy are not boundless, even if capitalism operates as if they were.15 One incentive for mobile phone and satellite conglomerates reaching out to the so-called O3B—the “other three billion” people on the planet who currently lack Internet access—is to be able tap a more global pool of affective labor. Plans for migrating poor people from the global south onto the Internet can be read as a beneficent cover for schemes to expand digital capitalism’s human resources. Within such conditions, offering more critical analyses and phenomenological accounts of infrastructure and affect in different sites around the world seems more important than ever.

Image Credits:

1. Broadcast Systems in the Former Yugoslavia, Image by Lisa Parks

2. Walking Phone Workers in Mongolia, Image by Lisa Parks

3. Cable Endings and Transmission Towers in California, Image by Lisa Parks

4. High through-put grain silo. Photo by Darin Barney

5. Call Center Workers

Please feel free to comment.

- This essay is a short version of a paper presented at the Media and Materiality workshop at New York University in March 2014. [↩]

- See Lisa Parks, “Where the Cable Ends: Television Beyond Fringe Areas,” in Cable Visions: Television Beyond Broadcasting, Sarah Banet-Weiser, Cynthia Chris and Anthony Freitas, eds. New York: New York University Press, 2007, 103-126; “Postwar Footprints: Satellite and Wireless Stories in Slovenia and Croatia,” in B-Zone: Becoming Europe and Beyond, Anselm Franke, ed. Barcelona: ACTAR Press, 2005; “Walking Phone Workers,” The Routledge Handbook of Mobilities, Peter Adey, et al, eds., London: Routledge, 2013, 243-255; and “Earth Observation and Signal Territories: Studying U.S. Broadcast Infrastructure through Historical Network Maps, Google Earth, and Fieldwork,” special issue on Earth Observing Media, Chris Russill, ed., Canadian Journal of Communication, Vol. 38, 2013, 1-24. [↩]

- For further discussion of infrastructural imaginaries and intelligibility see Lisa Parks, “‘Stuff You Can Kick’: Toward a Theory of Media Infrastructures,” Humanities and the Digital, David Theo Goldberg and Patrik Svensson, eds. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, forthcoming. [↩]

- Brian Larkin, “The Politics and Poetics of Infrastructure,” Annual Review of Anthropology, 42:1, 2013, 339. [↩]

- Melissa Gregg and Gregory J. Siegworth, The Affect Theory Reader, Durham: Duke University Press, 2010, 2. [↩]

- Darin Barney, “To hear the whistle blow: technology and politics on the Battle River branchline.” TOPIA: Canadian Journal of Cultural Studies, 25: Spring 2011, 7. [↩]

- Ibid, 8. [↩]

- Ibid, 7. [↩]

- Wendy Chun, Control and Freedom: Power and Paranoia in the Age of Fiber Optics, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2008. [↩]

- As Hardt and Negri explain, “Unlike emotions, which are mental phenomena, affects refer equally to body and mind. In fact, affects, such as joy and sadness, reveal the present state of life in the entire organism, expressing a certain state of the body along with a certain mode of thinking. Affective labor, then, is labor which produces or manipulates affects….” From Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri, Multitude: War and Democracy in the Age of Empire, 2004, 108. [↩]

- Brian Massumi, Parables for the Virtual: Movement, Affect, Sensation, Durham: Duke University Press, 2002, 45. [↩]

- Tiziana Terranova, Network Culture: Politics for the Information Age, Pluto Press, 2004. [↩]

- Mark Andrejevic, Infoglut: How Too Much Information is Changing the Way We Think and Know, New York: Routledge, 2013, 52. [↩]

- Daniel W. Smith, “Deleuze and the Question of Desire: Towards an Immanent Theory of Ethics,” in Deleuze and Ethics, Nathan Jun and Daniel W. Smith, eds. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2011, 137. [↩]

- Sarah Sharma, In the Meantime: Temporality and Cultural Politics, Duke University Press, 2014; and Jonathan Crary, 24/7: Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep, London: Verso, 2013. [↩]

Pingback: Week Three – ARTS3091 Advanced Media Issues

Pingback: Networked Dream Worlds — Real Life - l2com