“I wanted to hug the whole f*cking world.”: An Airborne Body in the Drone Age

Kevin Hamilton / University of Illinois

The August 18th, 1960 edition of the Universal Newsreel began with images from the Soviet trial of downed U-2 pilot Gary Powers, followed by a segment on Air Force balloonist Captain Joseph Kittinger’s “daring ascent into the stratosphere.” Viewers would have likely understood Kittinger’s record-setting flight and subsequent jump as part of the growing space race, but in fact the Air Force had designed Project Excelsior to help pilots like Gary Powers with the particular challenges of bailing out at the high altitudes required for airborne espionage. Though the newsreel narrator described Kittinger’s mission as “scientific,” the story’s placement after the Powers segment also served as a response to Soviet protest, as if promising continued espionage from even greater heights.

The same newsreel of Kittinger’s record-setting flight appeared again last January at the beginning of a video released on Youtube as an extension of a 30-second Super Bowl ad for GoPro, a camera company. Cropped and centered in the frame to create the illusion of a smaller and more antiquated format, the new presentation of the old sequence renders the Cold War firmly in the past. New footage interrupts the old newsreel, as we cut to a screen-filling, high definition view from the perspective of a contemporary high-altitude balloon belonging to “extreme” athlete Felix Baumgartner.

Excelsior and Stratos both took place in New Mexico. Kittinger seems to have designed the project very much based on his own, including the same training regime and number of total ascents. Stratos also stylistically mimics NASA projects of the 1960s; the day of his record-setting launch, Baumgartner emerged from the back of a silver Airstream trailer, and the operation also relied on a “Mission Control” reminiscent of the storied control rooms of Houston or Orlando.

Stratos producers designed the event for online presentation. Baumgartner’s descent streamed live over Youtube, with reports of over 8 million watching. The daredevil athlete broke the speed record for a human body exposed to the elements, encased in nothing but a suit. But the project was only possible through the accompanying eyes of viewers, setting their own record for simultaneous streams of a single video feed, just as sponsors had likely hoped. A human form screamed through the sky as servers somewhere far from view strained to accommodate the data load.

After the jump, Red Bull and GoPro released other cuts and a feature length documentary (the latter available only for subscribers to Rdio, the music streaming service). At the start of the longer documentary, we see a team originated by a phone call, and an effort built from scratch in the private realm. Where in the earlier Air Force operation, Kittinger performed as a stand-in for other pilots, taking on extreme conditions in order to design safer ways of withstanding them, Baumgartner is not only the sole pilot, but the very reason for the existence of the program. In 1960, Kittinger chose the flight suit he thought would make him most like other pilots; in the Stratos documentary, Baumgartner grows jealous upon seeing even one other trainee (a stand-in during a period of claustrophobia) wearing “his” pressure suit.

So what new “data” did Stratos produce? To answer this question, we should examine three key camera positions present in both jumps, as well as the time scales and viewerships they afford. Both experiments relied, among other points of view, on one camera position in the gondola, another from the ground, and a third on the jumper’s body.

For Excelsior, none of the views afforded a view in real time, and so could only serve as “data” after the fact. This temporality suggests at here http://samedayessays.org/ a forensic function – one of recovering what happened in the case of a negative outcome – namely, death of the jumper.

For Stratos, two of the three views – from the ground and from the gondola – afforded real time monitoring for project managers and online viewers. The key question in both experiments was whether the jumper would spin so fast as to lose consciousness and die; in the case of Stratos, new telescopic lenses and digital video afforded visible answers to this question from Baumgartner’s first step off the gondola.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_lEsLcGB7Vo[/youtube]

The resulting slow motion imagery of Kittinger is profoundly dreamlike, especially as viewed in the many edits that include multiple views of the same few seconds from different gondola cameras. The first three seconds of the Stratos drop, by contrast, communicates the matter-of-fact gravity of a body falling straight away from the camera. Where Kittinger appears as some sort of agent essay writer adrift (and even appropriated as such in a hauntological music video for Boards of Canada), Baumgartner appears as a human bomb.

From Excelsior to Stratos we move from government to private operations, from low-resolution to high-resolution, from a floating man in disorienting crisis to a falling man in seeming self-reliance. In both cases a man has traced the path of a bomb. But a final obvious shadow on this story is that where Kittinger’s efforts would help coax pilots aboard spy planes, Baumgartner’s took place at dissertation chapter 3 a time when airborne pilots were no longer needed for espionage or even attack. Surveillance pilots remain largely on the ground, bombs don’t fall straight down, and most high altitude aggressions take place in a dense network of visual analysis with, save leaks, little to no documents to show for it.

Image Credits:

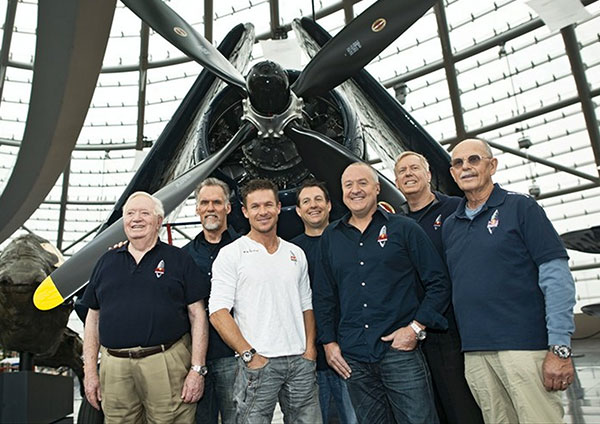

1. Felix Baumgartner, “Colonel Joe” Kittinger and the Stratos Team

2. Stratos Mission Control, Roswell NM

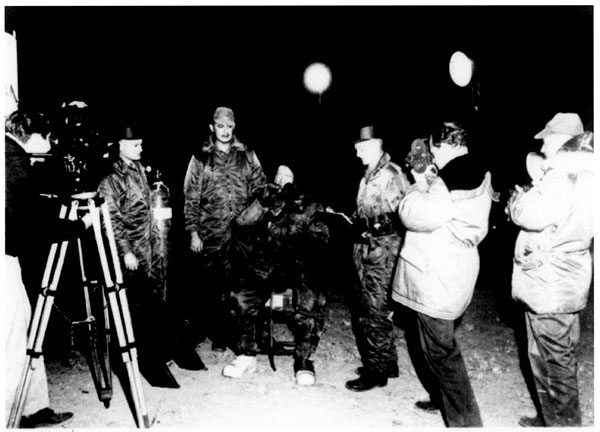

3. 1352nd Photographic unit of the USAF with Kittinger before ascent

4. A historic m45 artillery mount

5. Camera mount adapted from the M45 by the 1352nd Photographic Group, and likely used to track Excelsior

6. Camera afforded visibility of Stratos from the ground, run by the Flightline company

7. Kittinger viewed from a camera in the balloon

8. Baumgartner viewed from a camera in the balloon

9. What Kittinger saw

10. What Felix saw

Please feel free to comment.

Pingback: Turning the Lights Back On | Complex Fields