Female Specters: the Gothic Horror Films of Carlos Enrique Taboada

Kerry Hegarty/ University of Miami Ohio

Mexican horror director Carlos Enrique Taboada (1929-1997) is highly regarded in Mexico as one of the great talents of national cinema. He has influenced a generation of Mexican filmmakers, most famously Guillermo del Toro, whose films The Devil’s Backbone and Pan’s Labyrinth pay tribute to him. Taboada began his career as a screenwriter, and wrote the scripts for the four-film Nostradamus vampire series in 1959, and also wrote the screenplay for the 1962 film The Witch’s Mirror, which is widely considered one of the best-written Mexican horror films. He won two Ariel Awards (Mexican film academy awards) for Best Picture and Best Director for his 1984 film Poison for the Fairies. He is one of the few Mexican directors who chose to work in the horror genre (many others did so out of necessity during periods of industrial crisis). Though all of his films were low budget, he was, at his best, a master of ambiance and suspense, and his work still inspires filmmakers today.

Here I would like to consider the cultural importance of Taboada’s most famous cycle of films- his Gothic horror tetralogy, which includes the films Hasta el viento tiene miedo/Even the Wind is Afraid (1967); El libro de piedra/The Book of Stone (1968); Más negro que la noche/Blacker Than the Night (1974); and Veneno para las hadas/Poison for the Fairies (1984). These films might be considered the first modern Mexican horror films, as they all take place in a Mexico that was contemporary for the time, unlike the classic horror films that were popular from the 1930s to the 1950s, which were monster movies directly influenced by the Universal and Hammer horror studio films. These classic films generally took place during the colonial era, or else they featured modern people visiting or returning to pre-modern spaces like the ranch or the hacienda (as in the films of directors Juan Bustillo Oro and Fernando Méndez). Taboada’s films are some of the first to depict modern-day Mexico as the space of Gothic horror, in which supernatural forces from the past continually exist alongside and threaten to invade the present.1

One of the most significant elements of Taboada’s Gothic horror films-and one that merits more in-depth analysis than space allows here-is the symbolic role of their youth protagonists. The representation of these characters is especially significant within the context of Mexico’s ill-fated youth movement, which arose in 1968 as a protest against the government’s autocracy and was almost immediately quashed by the state, who afterwards maintained a secret police force dedicated to armed control of student gatherings. The conspicuous absence of any meaningful treatment of youth protagonists, especially female ones, in Mexico’s cinematic production of the time underscores the government’s ideological control of the medium. It also differentiates Mexico from other Latin American countries like Cuba, Argentina and Brazil who, in the 1960s, were spearheading politically charged “new cinema” movements.2 In Mexico, in spite of the cataclysmic social changes of the decade, film production consisted of light-hearted and escapist genre films, in which youth protagonists were either treated superficially or were expressly absent. Taboada’s Gothic horror films were some of the only exceptions to this.

As many horror theorists and scholars have posited, the horror genre is uniquely poised to do the cultural work of representing repressed historical forces. As such, it is possible to think about the films of Taboada as giving voice to some of these repressed cultural forces, especially with regard to the narrative constant of the young female as ghost or supernatural intermediary that is present in all four of his Gothic horror films.

The female ghost has a long tradition in Mexican cultural mythology, originating in the figure of “La Llorona,” or the crying woman, who, according to legend, drowned her children in a jealous rage when her husband left her, and to this day walks the night crying in search of them. Interestingly this figure makes an appearance in the earliest sound films in Mexico from the 1930s and 40s, and then reappears in films of the sixties, alongside those of Taboada, in a way that might be said to reveal a specific cultural anxiety surrounding the blatant transgression of female social norms (in this case, the maternal bond).

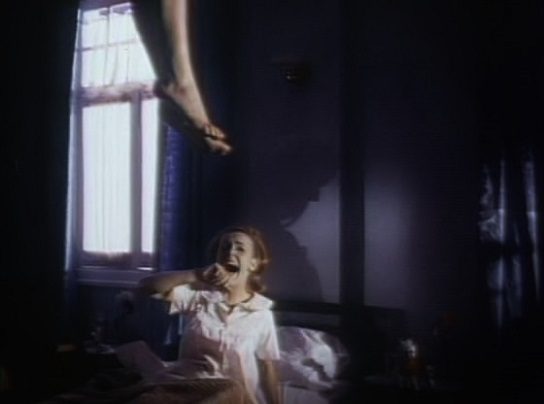

The female ghosts in Taboada’s films continue the legacy of La Llorona in that they all originate from a primordial broken maternal bond which is the unspoken root of their trauma. In Even the Wind is Afraid, which takes place at an upper-class girls’ boarding school outside of Mexico City, the main character is a young girl named Claudia who is haunted by recurring nightmares of a hanging girl calling her to the forbidden tower on the school grounds. Eventually she learns that a former student, Andrea, committed suicide by hanging herself in the tower a few years earlier, when the director of the school, Miss Bernarda, forbid her from seeing her mother before she passed away. Andrea eventually inhabits the body of Claudia, and in this way takes vengeance on the living and is able to put an end to Miss Bernarda’s strict rule, and have her replaced with a kinder, gentler headmistress.

In The Book of Stone, the protagonist is a young girl named Sylvia, whose mother has passed away, and who lives with her emotionally distant father and a stepmother whom she hates. Sylvia insists she has a playmate named Hugo, whose father was an evil magician from Austria, though the adults can only see Hugo as a stone statue in the garden. Sylvia’s father hires a kindly governess to take care of his daughter, but a series of supernatural events occurs and Mariana dies suddenly, while Sylvia’s father cuts the head off of the statue of Hugo in the end out of rage.

In Poison for the Fairies, the main character is ten-year old Veronica, whose parents died in a car accident years ago and who is being raised by her superstitious grandmother. As an outcast at an upscale boarding school, she claims that she is a powerful old witch in disguise, and befriends a new girl named Flavia, whom Veronica tries to induct into her world of black magic. In her attempt to control Flavia, Veronica becomes more and more cruel, until Flavia is forced to brutally avenge herself of Veronica in the end.

In all of these films, the female ghosts and/or young girls who convene with the supernatural are at the outset deemed dysfunctional by the oppressive forces of adult authority, who try to normalize and contain them.3 Eventually, however, the young girls are vindicated, as the monstrous surrogate mother figures they have been forced to bear (headmistress, stepmother, grandmother, etc.), are punished in the narrative at the end.

Even though these oppressive figures are justly punished, however, in most of Taboada’s Gothic horror films the young protagonist herself dies as well, which seems to raise an interpretive question: do these films effect a critique of the dominant ideology of Mexican society of the time (of patriarchy, conservatism, class privilege etc.), and offer a counter-narrative of resistance instead? Or do they reinforce a deeply-rooted cultural anxiety surrounding notions of female sexuality and subjectivity, which would have been brought to the surface by the social changes that were emerging both in Mexico and around the world in the late 1960s? Perhaps the answer is that they articulate the complexity of the social, political and cultural panorama of Mexico in the 1960s, in which transgression of authority was deemed a victory, though ultimately a victory that could not stand up to the deeply-rooted structures of a patriarchal, totalitarian state.

Image Credits:

1. Still from Taboada’s Even the Wind is Afraid

2. The statue of Hugo from Taboada’s The Book of Stone

3. Veronica and Flavia in Poison for the Fairies

Please feel free to comment.

- The lucha-libra films of El Santo, which emerged before Taboada’s Gothic horror films, deal with the supernatural past invading the modern-day world, though these films have more in common with the genre of fantasy than with horror. [↩]

- See Hegarty, K. “Youth Culture on Film: An Analysis of Post-1968 Mexican Cinema.” Studies in Hispanic Cinema. 4:3 (2007): 165-182. [↩]

- The only film that deviates from this construction slightly is Blacker than the Night, in which the ghost of an old woman exacts revenge on the young women living in her house, for their selfishness and irreverence. [↩]