Afterlife

Denise Bielby / University of California, Santa Barbara

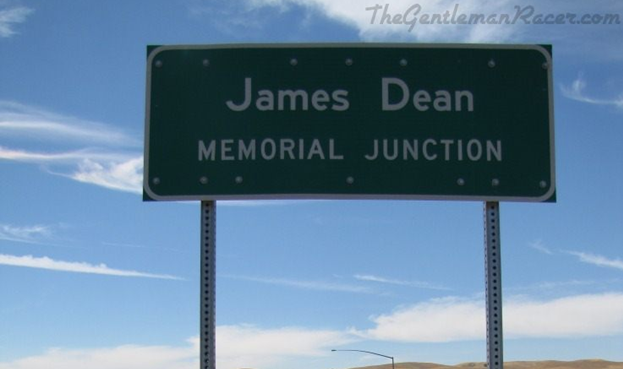

Memorial marking the site of James Dean’s death

On July 13, 2013, Glee’s Cory Monteith died in a Vancouver hotel room of a deadly mixture of heroin and alcohol. On November 30, 2013, in Santa Clarita, California, Paul Walker, of The Fast and the Furious franchise, was killed in a horrific car crash as the passenger in an ultra-high-performance Porsche driven by his financial adviser. On September 30, 1955, James Dean, the break-out embodiment of adolescent rebellion in the then-fledgling teen film market, totaled his Porsche race car and died on-scene while speeding to a dinner in Paso Robles, California. Sadly, as I write this there is now one more name to be added: Phillip Seymour Hoffman, from an overdose of heroin. These tragic deaths of valued younger actors register differently from those like Jean Stapleton’s, whose passing was brought about by natural causes after a long and storied career, or even James Gandolfini’s, who, although he died unexpectedly from a heart attack, at least had lived to middle age and had had the opportunity to be at the top of his game and acclaim. The loss of younger actors is particularly difficult to make sense of at many levels, not the least of which is from the haunting legacy of the “what-could-have-beens” that fill the wake left behind by an actor’s vivid impression on an equally vividly engaged audience.

Grief and grieving are not unknown to audiences. In fact, loss, grief, and grieving are central to the audience/consumer experience. They are, however, under-studied aspects of it. It’s not that these emotions are unrecognized by media analysts, in fact, quite the opposite. Popular television series that come to an end are routinely mourned for us by those who are tasked to speak for audiences (see, for example, Lloyd, 2013; Susman, 2003; Roush, 2013; http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2013/05/20/buffy-the-vampire-slayer-finale_n_3305813.html). The cancellation of popular, or critically acclaimed, or otherwise notable series and of long-running soap operas is marked publicly, and recognition of the significance of this lamenting has even made its way into the vernacular of other series, as is heard in the repeated sarcasm expressed by The Big Bang Theory’s “Sheldon Cooper” about the untimely early cancellation of Joss Whedon’s Firefly (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vB9iAuw8ZCE&list=PLA5C5FF44E78C8949). Public mourning is also not uncommon when popular characters in popular series are killed off unexpectedly (MI-5’s “Adam Carter,” Mash’s “Henry Blake,” the many losses in Game of Thrones, or Downton Abbey’s “Matthew Crawley”), but these deaths are different, especially when it is in service of the creative goals of the head writer or because it is the actor’s preference. What is worth noting, however, is that these mournings are more than “just” an obituary – the factual record of the details that made up a life. At its fullest, this media coverage is a highly visible collective expression of the deep personal significance of the actor, or character, or series, to our lives, to our culture, and, arguably, to the world.

However conscious we as cultural analysts may be of these public registerings, comprehending the underlying emotional experience of loss by audiences is not very well understood. There is, however, some scholarship that we can draw upon to guide us toward thinking more systematically about this. Foundational fan research recognized the importance of the affective economy of fandom1 , that is, the relevance and significance of where fans place their emotional investments according to their tastes – the mattering maps that differentiate one fan’s interests from those of another – that render as legitimate the expression of their emotional investments to themselves and to others. What one can draw from this early work is that not all losses are the same, depending on who or what is lost, and by whom, but that there are socially (as well as personally) legitimate reasons for a profound sense of loss. Another useful contribution to understanding the emotion expressed in these accounts can be derived from probing the importance of our cultural investment in satisfactory narrative closure2 . Conjoining work about the importance of the “good death”3 with Mittell’s typology of television endings4, Harrington illuminates the relevance of the cultural imperatives that coalesce into Western expectations for a “good textual death,” the expectation of not just an ending, but of the necessity for the ending that harmoniously achieves coherence, finality, and resolution of the narrative arc that led to it.2 The importance of this imperative cannot be underscored strongly enough, a fact readily observed and glaringly revealed when a show’s creator violates their established contract with fans. Fans’ seething outrage at ABC Family’s unexpected cancellation of its flagship show Kyle XY (http://mattdallasworld.blogspot.com/2013/01/kyle-xy-woe-and-why.html) or at Glee creator Ryan Murphy for the heartless erasure of the pivotal “heart-and-soul” contribution of Cory Monteith and his character “Finn Hudson” to the show (http://althemius.tumblr.com/archive/) are but two graphic examples, recognizing, of course, that in the television industry, network interference may also be a culprit in these destructive detours. Still, such perceived betrayals can not only terminate fans’ affective investments in a show, they can create bitter memories that endure in the landscape of fans’ long-term mattering maps.

Cory Monteith’s death in July at the age of 31 from mixed drug toxicity combined with alcohol meant his hit show,Glee, had to figure out how best to deal with his character. Monteith’s character, Finn Hudson, center, also died on the series, though the cause of death was not revealed.

How the cultural imperative about “good” textual endings applies to the premature death of a pivotal actor deserves special attention, because in these instances the death is a truncation of a career whose course will remain forever unresolved5. Here, established scholarship on survivor grief6 joined with emerging scholarship on the relevance of age, aging, and movement through the life course that accounts for how fans engage actors, characters, texts, and textual endings is useful7. Fan/actor/character/text interactions are complex: Fans age in tandem with actors, characters, and texts; texts age as time passes through the accretion of audience and industry memory, commemoration, and canonization, and may be re-signified in the process; actors and their characters may age asynchonistically; fans’ chronological age and location in the life course can affect how an actor or character or text is engaged initially and over time; and, nostalgia for and memory of what once was, or even the revisiting of what once was, can expand upon personal (as well as societal) meaning in uncharted ways8.

Why are these matters so important? A perhaps too obvious answer is the pervasiveness and facileness of social media; sentiment, as well as information, moves rapidly, and everywhere. What seems to be needed is a more systematic mapping of how audiences spend (more) of their lives engaged with such concerns through a variety of means that includes social media. To what extent are social media sites now, also, becoming a public space for the conduct of traditional cultural rituals such as mourning the death and preserving the memory of beloved cultural figures9. Another perhaps too obvious answer is the pervasiveness of celebrity culture. How can our understanding of it more adequately capture the significance of audience encounters with the loss of actors and texts and the reasons for the emotions that follow? The wealth of research produced in the second wave of fandom studies documented how fandom is integrated with modern life10, and yet there is still a great deal of work that remains to be done for the third wave on fans’ individual motivations, enjoyment, and pleasures. This entails, in particular, “furthering our understanding of how we form emotional bonds with ourselves and others in a modern, mediated world” (2007, p. 10). Very recent scholarship on how age and the kind of changes that come with it contribute to the social bonds that comprise the everyday life of audiences/consumers offers rich insight into the ever-deepening embeddedness of media in the lives of individuals in the 21st century11.

To be sure, the unexpected passing of an actor is not only a cause for grief and mourning, but also places untold personal as well professional demands on creative workers.

Director Douglas Trumbull said of the struggle to finish the project, “Getting the movie done was extremely heartbreaking and difficult.”

Paul Walker’s death may have put a halt on production of The Fast and the Furious 7, but director James Wan confirms that the film will not be abandoned.

The death of Philip Seymour Hoffman apparently won’t affect the release of the rest of The Hunger Games films in the franchise, as he had reportedly completed filming of most of his scenes as game master Plutarch Heavensbee.

Here’s a look at other celebrities who have died during the production of movies and TV shows.

Image Credits:

1. James Dean Memorial Junction

2. Glee

3. Natalie Wood

4. Paul Walker

5. Philip Seymour Hoffman

Please feel free to comment.

- Grossberg, Lawrence. 1992. We gotta get out of this place: Popular conservatism and postmodern culture. New York: Routledge. [↩]

- Harrington, C. L. 2013. The ars moriendi of US serial television: Towards a good textual death. International Journal of Cultural Studies, 6 (6): 579-595. [↩] [↩]

- Duclow, D. F. 2011 Ars moriendi: Encyclopedia of Death and Dying. Available at: http://www.deathreference.com/A-Bi/Ars-Moriendi.html [↩]

- Mittell, J. 2011. Preparing for the end: metafiction in the final seasons of The Wire and Lost. Paper presented at the annual meetings of the Society for Cinema and Media Studies. New Orleans, March. http://justtv.wordpress.com/2011/03/13/preparing-for-the-end-metafiction-in-the-final-seasons-of-the-wire-and-lost/ [↩]

- France, Lisa Respers. 2014. Philip Seymour Hoffman and other stars who died during production. http://us.cnn.com/2014/02/04/showbiz/philip-seymour-hoffman-stars-died-production/?iref=obnetwork [↩]

- Maciejewski, P.K., B. Zhang, S.D. Block, and H.G. Prigerson, H.G. 2007. An empirical examination of the stage theory of grief. Journal of the American Medical Association, 297 (7): 716-723. [↩]

- Harrington, C. L. and D. Bielby. 2010. A life course perspective on fandom. International Journal of Cultural Studies, 13 (5): 429-450; Harrington, C. L., D. Bielby, and A. Bardo. 2011. Life course transitions and the future of fandom. International Journal of Cultural Studies, 14(6): 567-590; Harrington, C.L., D. Bielby, and A. Bardo. Forthcoming. Aging, Media, and Culture. Lanham, MD: Lexington Press; Harrington, C. L. and D. Brothers, D. 2010. Constructing the older audience: Age and aging on soaps. The Survival of Soap Operas: Strategies for a New Media Era, edited by Abigail De Kosnik, Sam Ford and C. Lee Harrington. Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi. 300-14. [↩]

- Bryant, K., D. Bielby, and C. L. Harrington. Forthcoming. Populating the universe: The role of toys in adult lives. In Koos Zwan, Linda Duits, and Stijn Reijnders (eds.), Ashgate Research Companion to Fan Cultures. Surrey, England: Ashgate Publishing. [↩]

- Khatchatourian, M. 2013. “The memory of Cory Monteith lives on (and on) via Social Media.” Variety, July 31, 2013. Available at: http://variety.com/2013/digital/news/the-memory-of-cory-monteith-lives-on-and-on-on-social-media-1200569547/ [↩]

- Gray, J., C. Sandvoss, and C. L. Harrington. 2007. Fandom: Identities and Communities in a Mediated World. New York: New York University Press. [↩]

- Harrington, C. L. and D. Bielby. 2010. A life course perspective on fandom. International Journal of Cultural Studies, 13 (5): 429-450; Harrington, C.L., D. Bielby, and A. Bardo. Forthcoming. Aging, Media, and Culture. Lanham, MD: Lexington Press. [↩]

This is a fascinating and timely approach to various issues surrounding media’s relation to the unexpected death of an actor. I’m curious what the author thinks about the instructional aspects of these televised“good textual deaths”particularly in shows geared at young teens. While it is obvious that TV shows reflect and test social norms and boundaries, it is interesting to note the ways in which Glee and shows like it act under educational pretenses. After the airing of Finn’s memorial episode, it was complimented for being tasteful and for going“out of their way to step around the obvious” (http://nyti.ms/1mLr5Bi). But it also was criticized for not seizing the opportunity to teach young audiences another life-lesson about drug abuse. By not attributing a cause of death and including the impact it has on the remaining cast, it sets an authoritative example on proper grieving behavior and tradition as well. This“highly visible collective expression” creates a visual and narrative language on dealing with such issues that youth can then carry into social media and their every day lives. It teaches audiences by both setting an example for the consumer’s everyday behavior but also on a visual level how media can be used for such emotional outlets.

Early on in the article Bielby mentions the field’s understanding of the audience’s fandom and emotional mapping onto a fictional arc, and how Western notions of narrative closure need “coherence, finality, and resolution.”Social media serves as a device for the audience to shape their own culture and tradition of mourning in this style. Bielby rightly calls for studies to better understand the extent of this practice and its impact. This emotional attachment to media that extends over time opens up new channels of emotional interactions. For example, the Internet allowed for users to anonymously post crass humor about Montieth’s death. In this sense social media introduces reactions to death that would not typically be present in public.

The way in which emotional memory exists is also drastically changed by television and social media’s permanence. The continuous availability of both have been suggested by some to worsen our dependence on our own personal memory (see Wired’s discussion and summary of studies, http://wrd.cm/1hs7lkW). While it is hard to know how this impacts the memory of a dead actor or character, with further studies it would be interesting to know how social media users progress through stages of grief in comparison to non-users.