Media Fixes: Thoughts on Repair Cultures

Lisa Parks / University of California, Santa Barbara

A while back I published an article about TV repair that explored how technical knowledge about television sets circulated in the US during the 1950s and how that process was gendered.1 While conducting that research, and in an effort to deepen my understanding of TV’s insides, I visited a handful of TV repair shops in Madison, Wisconsin and talked to guys who had earned a living for decades by tinkering with and fixing peoples’ broken TV sets. The scattered parts I encountered in repairmen’s work shops (see Illustration 1) serve as apt icons for the entanglement of critical concerns brought forth by acts of repair — from resource economies to creative labor, from planned obsolescence to repurposing, from technological literacy to affective engagements. If there are currently more media devices in consumers’ hands than ever, what role does repair play in media studies? How might a focus on repair connect with Wolfgang Ernst’s work on the operative diagrammatics of media or Maxwell and Miller’s work on the “greening of the media?2 What kinds of media objects and sites lend themselves to a discussion of repair, and why?

During the past two years I found myself returning to the issue of repair while conducting research on the uses of mobile phones and computers in the rural community of Macha, Zambia.3 There, the issue of repair surfaced in ways that resonated with crucial recent research on repair by scholars Steven J. Jackson and Jenna Burrell, who have worked in Namibia and Ghana respectively. 4 Jackson’s path-breaking essay “Rethinking Repair,” calls for a shift away from modernist thinking about technology and embraces “broken world thinking,” which “asserts that breakdown, dissolution, and change, rather than innovation, development, or design… are the key themes and problems facing new media and technology scholarship today.” 5 His collaborative study of ICT repair in Namibia makes the compelling point that scholars tend to privilege “how communities embrace or adapt to new technologies” over “how they organize to sustain, manage, repurpose, or simply live with what they have.”6 Repair, according to Jackson, is a key yet understudied practice that is articulated with technological variation, the circulation of knowledge/power, and the ethics of care.

Jenna Burrell’s equally important study of ICT users in urban Ghana exemplifies how a focus on repair can productively complicate Western assumptions. As she describes the “ecosystem of distribution, repair, and disposal” that supports Accra’s Internet cafés, Burrell suggests the flow of secondhand computers from the US and Europe to Africa has resulted in discussions of e-waste that often ignore local peoples’ understandings of “what is reusable, what is valuable and what is truly waste.” 7 While Burrell acknowledges that secondhand computers can harm the environment and the health of handlers, she points out that their circulation also has facilitated “technical skill development and employment of Ghanian technicians who repair and refurbish nonworking machines locally….”8 Rather than treat repair as a sideshow to the global media economy, Burrell and Jackson position it as a vital dimension of contemporary technological understanding and critique. Building from their work, I offer below two brief scenarios of repair in Macha, Zambia to highlight relational and affective dimensions of repair cultures.

Open-Air Repair

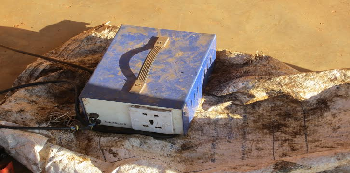

Just off the dirt road leading to Macha’s center, Berian Menyani works at a makeshift repair shop on a small patch of cement outside an abandoned shop where people from the area drop off broken generators, radios, power converters, and other objects, hoping they can be repaired. The objects are arrayed around Menyani as he kneels, crouches or sits on the ground, and, works with a few coveted tools. He cracks things open, pulls the pieces apart, lays them on pieces of cloth, tries to identify the problem, figures out a solution, finds or makes needed parts, and puts machines back together in an effort to extend their lives. Radios or mobile phones are fixed alongside and sometimes in relation to other objects such as small engines, bicycle wheels, or pumps, which support daily life in this agricultural community. Rather than being a specialist (a la the TV repairman) Menyani adopts a relational multi-object approach. Skill and knowledge aggregate through regular and rigorous tactile engagements with different kinds of technical objects rather than via mastery over one thing. When there is a conundrum in repairing one object, another is tackled, and the solution for that repair may inform others.

Since Menyani works outdoors in an openly visible area trafficked by passersby, his repair work is public and performative and draws attention from community members. Customers and friends often gather around to talk and watch. Here, repair not only extends the use value of objects but becomes a mechanism of social interaction. The recurring act of repairing things in the open-air transmits the message that things can be fixed when they fail rather than thrown away. Relational, open-air repair has the potential to extend the social circulation of technical knowledge by bringing people together to watch and talk as different kinds of machines are opened, manipulated, fixed, and re-circulated. Such practices also work to destabilize the logic of the black box.

Guarding a Mobile Phone Tower

Near the center of Macha, a forty-meter mobile phone tower looms above the community, its base surrounded by a spiked fence topped with barbed wire. Installed in October 2006, the Airtel-owned tower hosts transponders for Airtel and competitor MTN and provides commercial mobile phone service to people throughout the area. A Machan man I interviewed (who prefers to remain anonymous) helped dig the hole for and install the tower in 2006. Immediately after the installation, Airtel hired him to be the tower’s guard. For the past seven years, he has spent almost every night from 7:00 p.m. until sunrise sitting on a thin bench in a narrow metal box, listening in the dark for trespassers, getting up periodically to check around the site. If there are any problems, he is to call emergency numbers at Airtel and MTN, though neither company provides him with a mobile phone or buys him talk time. He earns 250 kwachas per month (about $50 USD) and uses this income to support a family of seven people who live ten miles away from the tower. The tower guard takes pride in the fact that there have been no major problems since he began this work and believes that if something were to go wrong he would be individually blamed and held responsible, possibly even punished or imprisoned.

While tower guarding might be thought of as security work, this kind of labor also falls within the rubric of repair since its purpose is not only to protect property but also to prevent service interruptions. Put another way, this tower’s smooth operation is inseparable from this guard’s presence, time, and attention. Having monitored the tower’s functioning night after night, month after month, year after year, he has learned which electronic buzzes are normal and what it sounds like when there is a power outage and the generator is activated. He also has learned to listen to movement around the site in the dark and distinguish the sounds of an animal’s movements from a human’s. As Jackson astutely observes, repair is not just about fixing things; it involves maintaining or caring for them as well, and as such is articulated with the “ethics of care.”9 During the past decade, mobile phone tower guards have been hired worldwide to perform similar work. My conversation with Macha’s tower guard suggests this work exceeds mere functionalism and extends into the realm of affect. The guard’s descriptions of his work oscillated from boredom to fear, pride to contempt, privilege to exploitation, revealing that the labor of repair is part of affective human-machine dynamics that demand deeper investigation.

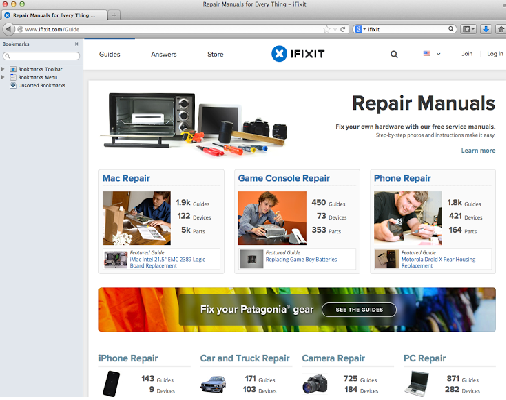

It is my hope that critical work on repair will continue in media studies across different axes of social and national/local difference and in relation to different kinds of technical objects. In the US, an active “teardown culture” has recently emerged as manifest by the book Things Come Apart and the website ifixit.com, which cleverly insists on consumers’ “right to repair.”10 While these cultural sites have immense potential to extend the social circulation of technical knowledge, they sometimes link repair to a heroic masculinity more preoccupied with restoring order or turning the insides of machines into spectacles than tackling social issues. In classic high-tech speak, ifixit.com promises to be “the free repair guide for everything written by everyone” yet on the website’s “Repair Manuals” page only white men appear fixing machines; women and people of color are absent.11 Such images are not only evocative of 1950s discourses on TV repair, but suggest the need to approach the breakdown of things as opportunities to imagine social fixes as well.

Image Credits:

1. Electronic Parts in a TV Repair Shop, Photo by Author

2. An Open-air Repairman, Photo by Author

3. A Power Convertor Awaiting Repair, Photo by Author

4. A Mobile Phone Tower, Photo by Author

5. Screen Shot of ifixit.com’s “Repair Manuals” page, Photo by Author

Please feel free to comment.

- Lisa Parks, “Cracking Open the Set: Television Repair and Tinkering with Gender 1949-1955,” Television and New Media, Aug. 2000, vol. 1 (3), pp. 257-278. [↩]

- Jussi Parikka “Operative Media Archaeology: Wolfgang Ernst’s Materialist Media Diagrammatics,” Theory, Culture and Society, 2011, vol. 28 (5), 52-71; Wolfgang Ernst, Digital Memory and the Archive, Jussi Parikka, ed. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013; Rick Maxwell and Toby Miller, Greening the Media, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012. [↩]

- This research is related to a four-year interdisciplinary study with Elizabeth Belding entitled, “VillageNet: Intelligent Wireless Networks for Rural Areas,” funded by the National Science Foundation, 2011-2015. I thank Chief Macha, Consider Mudenda, Lindsay Palmer, Abby Hinsman, and the people in the community of Macha for helping with this research. [↩]

- Steven Jackson, Alex Pompe, Gabriel Krieshok, “Repair Worlds: Maintenance, Repair, and ICT for Development in Rural Namibia,” CSCW’ 12, Feb 11-15, 2012, Seattle, Wa.; Jenna Burrell, Invisible Users: Youth in the Internet Cafés of Urban Ghana, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2012. [↩]

- Steven J. Jackson, “Rethinking Repair,” Media Technologies: Essays on Communication, Materiality and Society, Tarleton Gillespie, et al, eds. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2013, p. 222. [↩]

- Steven J. Jackson, Alex Pompe, Gabriel Krieshok, “Repair Worlds: Maintenance, Repair, and ICT for Development in Rural Namibia,” CSCW’ 12, Feb 11-15, 2012, Seattle, Wa., p. 1. [↩]

- Burrell, Invisible Users, p. 161, p. 181. [↩]

- Ibid, p. 181. [↩]

- Jackson, “Rethinking Repair,” p. 231. [↩]

- Todd McLellan, Things Come Apart: A Teardown Manual for Modern Living, Thames and Hudson, 2013. [↩]

- “Repair Manuals,” IFIXIT website, available at http://www.ifixit.com/Guide, accessed Dec. 3, 2013. [↩]