Cult Streaming: Warner Archive Instant

Derek Kompare / Southern Methodist University

The rapid rise of streaming media over the past few years has altered the media landscape in many significant ways. While the shift of media access over the past few decades from ephemeral experience, to physical object, to downloadable file, and back to ephemeral experience has been subtle and overlapping, it has had profound consequences for the way media works are conceived, produced, distributed, and consumed.

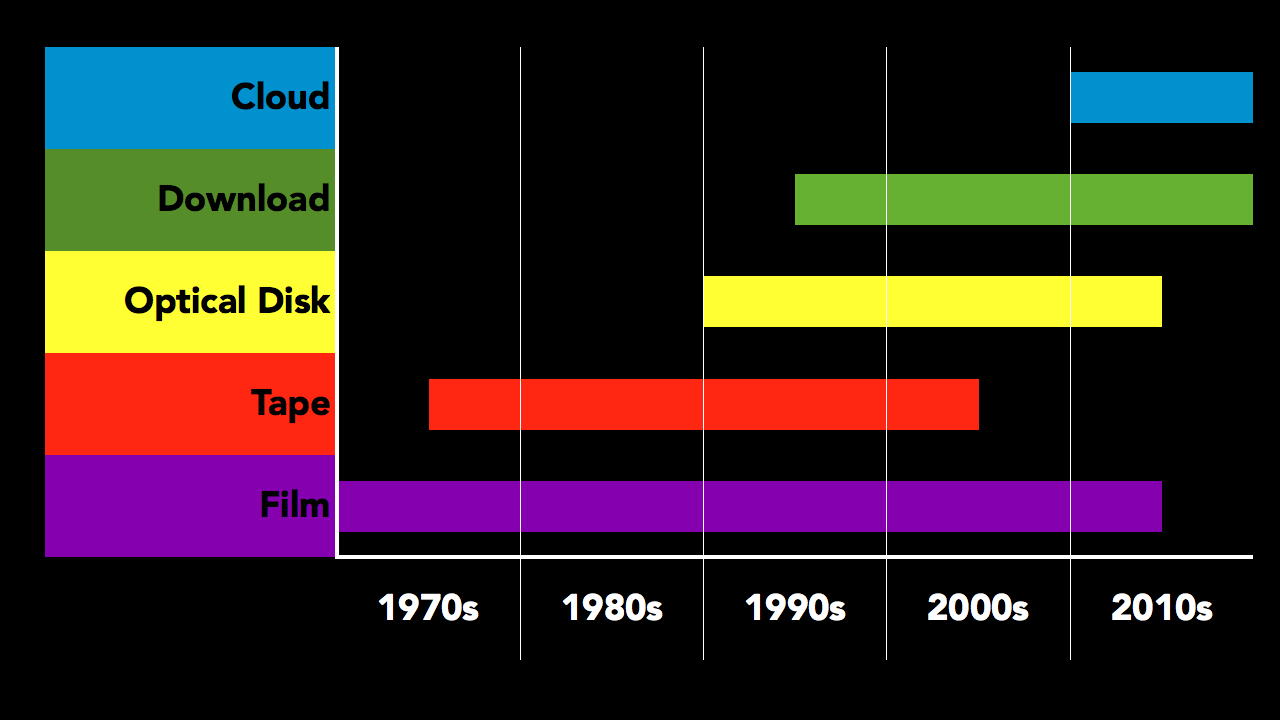

We are deep along a transition from physical to virtual media objects, and while its parameters and pace are certainly debatable, the overall trajectory is not:

As this chart indicates, over the past few decades the prominence of audiovisual media objects in the culture has gradually moved from analog to digital, and from tangible to remote. The steep decline in the sales and use of physical audiovisual media objects in the recent past has been particularly impactful. The default availability of films and TV programs as tangible consumer products (as tapes in the 1970s-90s, or discs since then) has long been taken for granted, but is starting to recede as mature markets plateau and fall, and digital devices increasingly marginalize disc playback, or, more commonly in a WiFi-ed era of phones, tablets, and lighter laptops, leave it out entirely.

This transition has been, and deserves to be, a key locus of analysis and debate across the culture, and especially within media studies. Scholars like Wheeler Winston Dixon1 and Chuck Tryon 2 have provided especially insightful investigations of this shift so far, focusing in particular on the impact on the production and distribution of film. However, in exploring these digital media practices, we should also consider how they diverge. Despite blanket descriptions of “the digital,” and some industrial calls for technical standards, there are still relatively few common digital forms, practices, and interfaces. This is not “a” transition, but many.

Among these, the movement of older extant media works to digital platforms is a particularly important transition. As physical media declines, accessible digital versions (whether rented, sold, or streamed) are key in maintaining the historical connection to these works. Just as syndicated and cable television and home video were instrumental in the wider circulation of film and television history, so the internet must be now if similar relationships to the media past are to continue.

One iteration of the streamed past can be found at Warner Archive Instant (WAI), the streaming version of the Warner Archive home video label. Wholly-owned by Warner Bros. Entertainment, Warner Archive is a manufacture-on-demand (MOD) DVD label focusing exclusively on past films and television shows at the margins of the market. Their offerings are typically too obscure for mass retailing, but nonetheless still too lucrative to leave entirely off the shelf. Thus, it is aimed primarily not at general media consumers, but rather to fans who seek out particular genres and figures: pre-code melodrama, sixties noir, made-for-TV movies, or actors like Jack Palance, Jeanette MacDonald, and John Saxon. Typical label releases include films like the Crime Does Not Pay shorts (1935-47), the sex comedy Pretty Maids All In A Row (1971), and the post-apocalyptic drama The World, The Flesh and the Devil (1959); and TV shows like the western Sugarfoot (1957-61), the Saturday morning adventure Thundarr The Barbarian (1980-82), and the sitcom Bridget Loves Bernie (1972-73). WAI streams many (though not all or even most) of the titles available in the Warner Archive collection for a monthly subscription fee of $9.99.

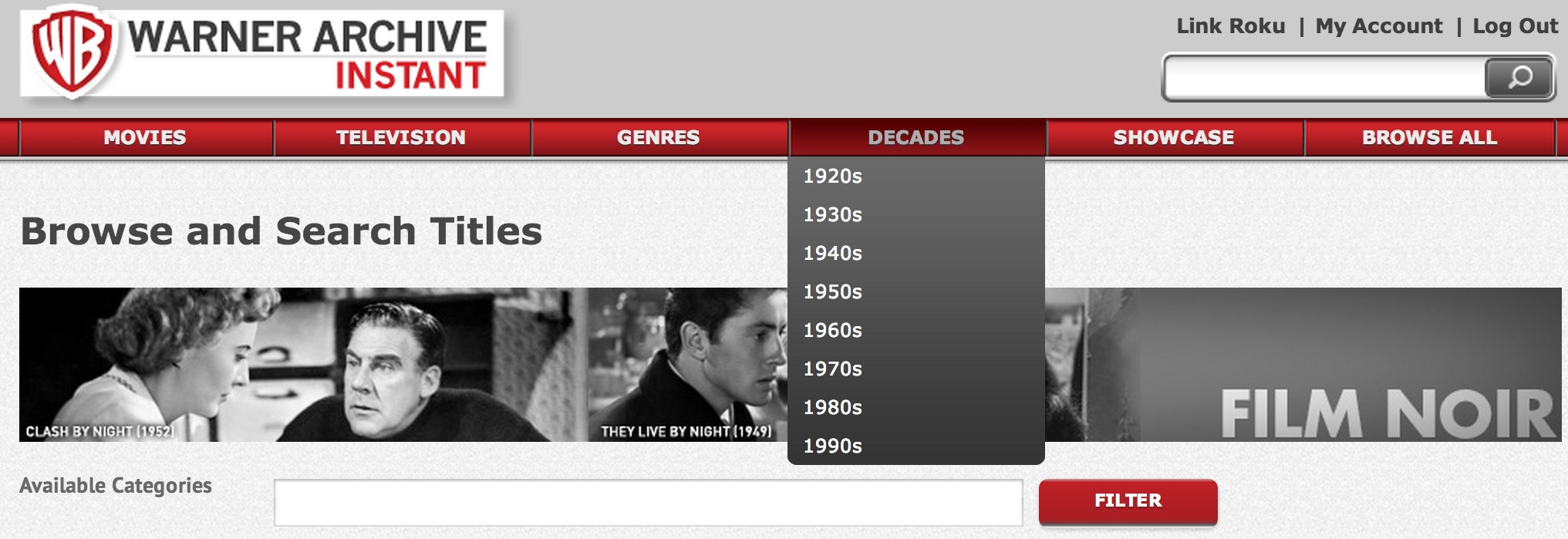

By focusing on these titles, rather than more well-known and mainstream fare, WAI aims itself precisely at fans of myriad “cult” sensibilities. As Matt Hills3 has argued, the “cult” designation of any work is impossible to fix, as it is produced by the combination of textual features, media discourses, and fan practices (rather than any one of these factors). WAI encourages all three of these angles through its social media outlets (including a lively Twitter account, podcast and YouTube channel), and its curation practices. While any title, actor, or director in the site can be found in a search (as with all streamers), WAI is also distinctly organized by format, genre, decades, and special, periodic “showcases.” Thus, fans of “television,” “mondo/cult,” “1970s,” or “On Location: Los Angeles” could all use those categories to browse for content on WAI.

WAI’s classification schema isn’t unlike more “traditional,” pre-digital forms of curation, including libraries, theaters, cable TV networks, and media studies scholars, programs, and publishers. However, unlike more well-known streamers like Hulu, Netflix, or Amazon, WAI’s focus on cinematic and televisual marginalia (and mostly Hollywood marginalia at that) locates it as a boutique streamer. It does not provide something for everyone (as the top streamers all purport to), but rather markets its more limited fare to a limited audience. It has adopted the strategy of a narrowcast cable channel or specialty video label (as Warner Archive itself still is), but to a monthly subscription model, rather than advertiser-supported (as most cable channels still are) or direct payment (e.g., purchasing a DVD). It is not the only streamer which follows this model–other services with similarly limited fare include Crunchyroll (anime), Viki (global TV), Fandor (indie films), and SnagFilms (indie films)–but so far it is the only one to occupy its particular niche of half-forgotten Hollywood. While it lacks the scope and access of the major streamers (e.g., so far the only way to watch its fare is via its often-problematic website, or through a Roku box), it nonetheless connects to a smaller audience for whom some convenience may be sacrificed for audiovisual quality and eclecticism.

Ultimately, WAI’s curation practices are where the “old” context of physical media and “new” context of boundless streaming connect. By offering up material that would not otherwise be accessible, WAI, like its parent video label, and other similar commercial reissue ventures (e.g., Shout! Factory, Kino, Something Weird, Fantagraphics) serve as de facto archives of 20th century media culture that might otherwise be forgotten. In Digital Cultures, Milad Doueihi 4 writes that the digital transition “has the potential to alter our historical perspective and inform the ways in which we define and understand the notion of a record, of historical record, and the narratives we will be able to produce about the events that determine our cultural history” (122). As the physical record gives way to the virtual, we need to continue to monitor this transition, accepting both its advantages and limitations, but interrogating its presumptions, textures and depths.

Image Credits:

1.Media Transition: author-made chart

2.Warner Archive Instant: screengrab of Warner Archive Instant website, owned by author

Please feel free to comment.

- Wheeler Winston Dixon, Streaming: Movies, Media, and Instant Access (Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky, 2013). [↩]

- Chuck Tryon, On-Demand Culture: Digital Delivery and the Future of Movies (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2013). [↩]

- Matt Hills, “Defining Cult TV: Intertexts, Texts, and Fan Audiences,” in The Television Studies Reader, ed. Robert C. Allen and Annette Hill (New York: Routledge, 2004) 509-23. [↩]

- Milad Doueihi, Digital Cultures (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2011). [↩]

Pingback: My 3 Words # 31 | emilykarn

Pingback: Past Media, Present Flows Derek Kompare / Southern Methodist University | Flow