Shipper Fandoms and Online Polls: Reconsidering Critiques of Clicktivism

Eve Ng / Five College Women’s Studies Research Center and the University of Massachusetts-Amherst

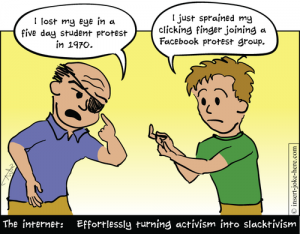

In 2010, two articles critical of digital activism appeared: Malcolm Gladwell’s discussion [click here to access] of what he termed “slacktivism” in The New Yorker and Micah White’s article [click here to access] on “clicktivism” in The Guardian. While their focuses were slightly different – Gladwell was discussing social media such as Twitter and Facebook, while White highlighted tactics used by progressive sites Moveon.org and TckTckTck – both argued that activities that consist of “clicking a few links” or sharing them on Facebook are at best ineffective and at worst detract from offline practices that have previously characterized effective social change. These critiques have sparked various responses (e.g. see Silberman, 2011)1, which I cannot completely summarize here. Instead, I want to insert into the discussion the involvement of fandoms in online entertainment polls and consider what this suggests about not just different types of digital participation, but how the social locations of media users inform their engagement.

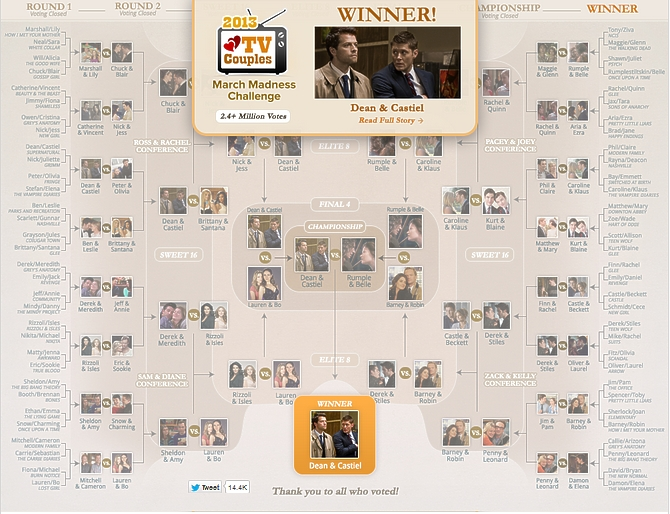

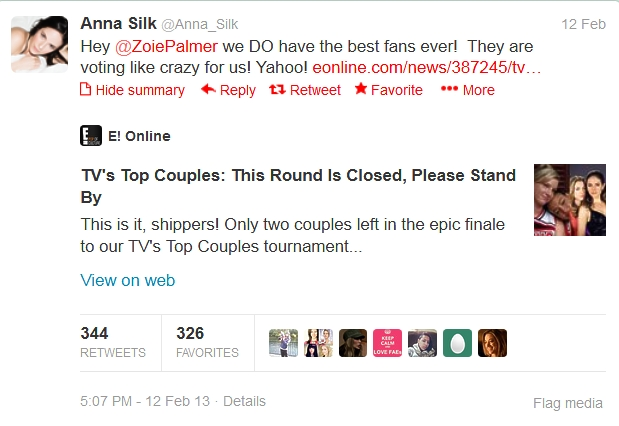

At first blush, it seems easy to apply the clicktivism tag to voting on polls for fictional television (or, less commonly, film) couples. These polls are run by mainstream entertainment websites such as E! Online, Zimbio, and Entertainment Weekly, as well as sites with more narrowly targeted users such as Wetpaint (aimed at young women), AfterEllen (lesbian/bisexual women), and Backlot (formerly AfterElton, aimed at gay/bisexual men). Because being able to vote more than once is the norm – some sites have a once an hour limit, while others only prohibit automated scripts – fan communities mobilize members (typically via Tumblr and message boards) to vote as constantly as possible, preferably around the clock. One tactic is to marshal those living in non-U.S. timezones to vote during the American nighttime hours; it was quite possibly through such means that the Doccubus fans of SyFy’s cult show Lost Girl beat Glee’s huge Brittana fandom in this year’s Valentine’s Day E! Online poll [click here to access]. Furthermore, with a popular format being “March madness” brackets akin to those for U.S. college basketball tournaments, multiple rounds of voting are often required; it takes 6 rounds to narrow down a bracket of 64 couples to the eventual champion. There is therefore a certain amount of organization and labor associated with successful online voting.

Some might be tempted to dismiss these fan practices, both because the most popular polls occur on commercial sites and hence comprise the mainstreaming of media user “participation” more generally and because the outcomes of these polls are not determinative of any canonical narrative directions. I would like to suggest, however, other ways to weigh the impact of these polls, and – more importantly – the need for considering poll participation in terms of the positionality of the voters and the broader context of their motivations.

An avenue for queer visibility

First, it is no accident that same-sex couples, both canonical and non-canonical, have featured prominently even on mainstream polls, such as Rachel/Quinn (“Faberry”) on Glee or Dean/Castiel (“Destiel”) on Supernatural [click here to access], and for these fandoms, coming out on top of numerous canonical straight couples is an especially satisfying result for queer visibility. In addition, another common goal is to signal to showrunners that the pairing has significant support, so even if a romantic relationship between two characters would never be depicted on the show, perhaps they could enjoy increased screentime. Also, actors themselves sometimes become involved in encouraging fans to vote, so polls provide an appealing avenue for demonstrating fan support as well as fan-performer interactions.

Mainstream media certainly circulate representations that maintain dominant norms, but at critical moments, they have also provided powerful challenges to the status quo. In fact, in his response to Gladwell (2010), Brandzel (2010)2 argued that media visibility was a key component of even pre-Internet movements, including the civil rights protests that Gladwell discussed, by showing viewers elsewhere what is possible. Online polls do not have the same audience and are not intended to incite the same sorts of actions, but when they result in victories unexpected by general audiences, queer fan imaginaries that have been skirting mainstream and margins are become widely visible, if only for a moment.

Digital activism and positionality

In an early account of fan activism online, Shefrin (2004)3 framed the emerging dynamics as forms of “participatory fandom,” and Jenkins (2006) significantly expanded the discourses of fan participation. Yet with the tide having turned significantly against “digital optimists” in recent years, Jonathan Sterne’s (2012)4 [click here to access] comments in a Flow article last year are more typical, when he asked whether interactivity is the new passivity:

“What if all the bad things that media critics have been [saying] about passivity for the past century or two are now equally applicable to all the demands to interact, to participate? What if interactivity is now one of the central hinges through which power works?”

Coupled with critiques like Gladwell’s (2010) and White’s (2010)5, digital participation seems to have lost much of its lustre amidst exhortations to return to more traditional forms of activism. But missing in these discussions is an acknowledgment of the different social locations of activists, or media users more generally. Though generally unstated – and such unstating reveals the familiar privileged positions of unmarked gender, racial, and class categories – critics of the slacktivist seem to envision white, male-bodied, cis-gendered individuals who are taking the easy way out on their electronic devices rather than doing something more meaningful.

Nevertheless, people with differently embodied identities experience different risks and challenges in physical forms of activism. Scholarship on the Occupy movement, for example, has highlighted the challenges experienced by women (Anonymous, 2012), people of color (e.g. Campbell, 20116; Juris, Ronayne, Shokooh-Valle, & Wengronowitz, 2012)7, trans people (Ng & Toupin, in press)8, as well as those who could not easily set aside work and family commitments for long-term presence at the encampments (Smith & Glidden, 2012). Of course, this has not prevented such participants from being instrumental in Occupy and many offline mobilizations, and not all offline action involves street protest—letter-writing and phone calls have long been considered more effective than emails, for example. However, we should also be careful not to categorically privilege physical presence as if everyone were equally well-positioned to make that choice.

The corollary is not to treat or dismiss all forms of online activism as the same enervated beast. One case of vocabulary slippage occurred in a recent Al Jazeera article [click here to access] critiquing the Kony 2012 campaign, where the author referred to “clicktivism, or internet activism” as if the two were equivalent. Counter to this perspective, John (2010)9 [click here to access] discussed the online-only actions associated with Wikileaks, while others such as Carr (2012)10 [click here to access] and Manilov & James (2010)11 [click here to access] have detailed how social media can be key in bringing about “big change” and not, as Gladwell (2010) argued, generally serve only as a way to disseminate information.

As for online entertainment polls, the passionate involvement of media fandoms doesn’t quite fit the weak ties involvement that Gladwell (2010) attributes to typical Facebook and Twitter activities, and the Internet offers numerous spaces for fan solidarity, including shippers of every ilk. This isn’t to claim that such online communities aren’t themselves stratified or implicated in dominant discourses; even queer fandoms overwhelmingly favor normative gender expression, if poll results are anything to go by. Still, counter to sweeping dismissals of clicktivism, I suggest examining how voters negotiate their varying levels of cultural agency, and situating their investments and actions within a larger, complex field of digital participation.

Image Credits:

1. The New Yorker Logo

2. Zimbo: March Madness Challenge 2013

3. Anna Silk Tweet

4. Slacktivism Cartoon

Please feel free to comment.

- Silberman, M. (2011, January 6). Looking for what works: Best online organizing reads of 2010. Huffington Post. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/michael-silberman/looking-for-what-works-be_b_804871.html [↩]

- Brandzel, B. (2010, November 15). What Malcolm Gladwell missed about online organizing and creating big change. The Nation. http://www.thenation.com/article/156447/what-malcolm-gladwell-missed-about-online-organizing-and-creating-big-change

Gladwell, Malcolm. (2010, October 4). Small change: Why the revolution will not be tweeted. The New Yorker. http://www.newyorker.com/reporting/2010/10/04/101004fa_fact_gladwell?currentPage=all

[↩] - Shefrin, E. (2004). Lord of the Rings, Star Wars, and participatory fandom: Mapping new congruencies between the Internet and media entertainment culture. Critical Studies in Media Communication, 21(3), 261–281. [↩]

- Sterne, J. (2012, April 9). What if interactivity is the new passivity? Flow, 15(10). http://flowjournal.org/2012/04/the-new-passivity/

[↩] - White, M. (2010, August 12). Clicktivism is ruining leftist activism. The Guardian. http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/2010/aug/12/clicktivism-ruining-leftist-activism [↩]

- Campbell, E. R. A. (2011). A critique of the Occupy movement from a black Occupier. The Black Scholar, 41(4), 42–51. [↩]

- Juris, J., Ronayne, M., Shokooh-Valle, F., & Wengronowitz, R. (2012). Negotiating power and difference within the 99%. Social Movement Studies, 11(3–4), 434–440. [↩]

- Ng, E. & Toupin, S. (in press). Occupy and feminist practice: A case study of online and offline activism at Occupy Wall Street. Networking Knowledge. [↩]

- John, J. (2010, December 9). Operation Avenge Assange as digital direct action. Read Write. http://readwrite.com/2010/12/09/operation_avenge_assange_as_digital_direct_action [↩]

- Carr, D. (2012, March 25). Hashtag activism, and its limits. New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2012/03/26/business/media/hashtag-activism-and-its-limits.html [↩]

- Manilov, T. & James, M. (2010). Movement building and deep change: A call to mobilize strong and weak ties. Huffington Post. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/taj-james/movement-building-and-dee_b_765362.html [↩]

As a fervent Tumblr and Twitter user, I’ve seen my fair share of ship polls, or, as this article would like to suggest, internet activism. I’ve seen ship polls hosted on all the sites mentioned – E!, EW, Wetpaint- and more. I’ve seen all different types of polls – vote once, vote once per hour, once per day, and nonstop. I’m also familiar with all of these ships and have even voted for some of them in some polls. On average, I probably see, at least, one ship poll per day. Sometimes I take part in them, sometimes I don’t. I’m certainly not as involved as some of my peers though. I know people who just sit there all day, every day, just clicking, like they have nothing better to do, no job or school to get to. With so many people voting, including computers sometimes, it can be incredibly hard to win an online poll. What I don’t get is what the voters of these polls are desiring their win to do. Why put in all this energy? What are they trying to prove? The way I see it, ships polls are just created so that the sites hosting them can generate hits. I like the idea that voters think that if their ship wins the poll they might get more screen time, but these polls don’t influence the canon, as many writers and producers have said before. I’d love to hear from someone who votes constantly as to why they vote. For me, it’s just so that I can feel like I’m supporting my ship and my shipmates.