We Resign from Sexism and Games Effective Immediately: Positive Steps Toward Gender Equality in Gaming Cultures Jennifer deWinter / Worcester Polytechnic Institute Carly Kocurek / Illinois Institute of Technology

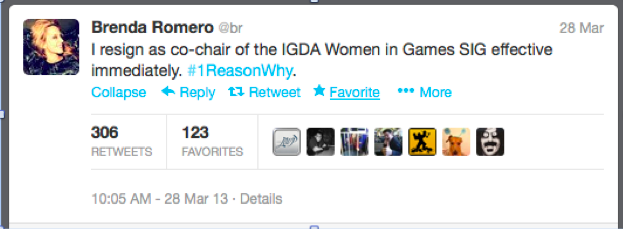

We know, we know… Every time we start one of these columns, we begin with yet another appalling anecdote from the game culture that emphasizes gender disparity in and around games. And this month is no different because the 2013 Game Developers Conference in San Francisco just wrapped up, and one of the most talked about, blogged about, and tweeted about stories comes from the surprising resignations of Brenda Romero and Darius Kazemi from IGDA.

A resignation might not be so shocking within itself. A resignation at the major institutional event might add to a sense of surprise and bewilderment. But it is the hashtag on which this message was tweeted—#1reasonwhy (see our last column)—that hints at a deeper problem. Brenda Romero had just presented on the panel #1reasontobe at the GDC in which she and other game developers were making a case that there are many reasons for women to join the game workforce. Later that evening, there was an industry party co-sponsored by IGDA and YetiZen at which scantily clad young female dancers (or models, or paid gamers – reports vary) entertained the audience on stage.

After months of media attention and a maelstrom of editorials, blog posts, and news reports about women and gaming, the timing on this particular form of entertainment was bad, to say the least. People were outraged at the sexism! People resigned from official posts! Official statements were made.

In response to this, other people were outraged that the feminists were at it again (many comments explain that “it’s just a party!”). Other people scoffed at Brenda Romero’s resignation (Kazemi’s resignation was apparently less worthy of scorn). And more official statements were made.

Interestingly, a similar event was hosted at GDC 2012, and while some people expressed their disgust, there were no public condemnation of the event. Fast-forward a year, post Anita Sarkeesian, post #1reasonwhy, post a lot of public and industry discourse, and the response is markedly different. This is not a criticism of industry hypocrisy—“last year it was okay, but this year it’s not.” This points to something much more positive:

Industry expectations are changing.

Reshaping the Future Industry

In writing about sexism in gaming, there is an impulse to throw up our hands and say, “Well, what can be done?” We would argue a lot can be done, and in fact, many individuals and organizations are already working toward building a more inclusive gaming culture. But this inclusivity, like many cultural changes, requires multiple institutions to change how they approach women and games. Below, we offer concrete suggestions and references to resources that might help:

Diversify Representations in Games

There are simply fewer female avatars in games—significantly fewer. That is not to say that there are not representations of females in games as secondary or supporting characters. However, these characters tend to be objects of desire. That desire is constructed through the female as the reward for the win condition (think Mario and the Princess) or a desire for a sexualized being. You may think that we are about to say get rid of this type of representation. We are not. We would argue not for less sex, but for more. Drawing on E. Ann Kaplan’s work on music videos’ depiction of sex and sexuality, we would suggest the problem with the “sex sells” mentality so prevalent in the game industry is not its mere presence, but rather the narrowness of that vision.1 Not every game needs to make direct overtures to the heteronormative male gaze. Diversifying representations exposes players to a wider variety of characters, which obviously affects the player experience and allows for various forms of identification. Further, players often become designers, and a designer’s toolbox is comprised of what came before.

Institutionally Support Women in Games

The gaming industry is beginning to professionalize. We can see this in the rise of the game program at universities, the contemporary discussions about institutionalizing a “game maker’s guild” in the same way that there is a “screen actors guild,” and formalized mentoring in the industry. These professionalization attempts mean that institutions are poised to teach and lead the next generation of game designers. For example, game design programs at some universities have taken a proactive approach to recruiting and retaining more women students. Some of the strategies employed are so common sense that it’s appalling more programs aren’t already doing these things. For example, a faculty member from one university explained how the demo reels of student games did not feature a single female student designer. And this program had graduated famous female designers. By including women on these demo reels, in the promotional materials, and as speakers at recruiting events, this faculty member reported that female enrollment had jumped from just above 10% to approximately 30% in just a couple of years.

In addition to universities representing their female student body, the Entertainment Software Association, Sony Entertainment, and Google have all invested significant funds into scholarships and educational programs intended to recruit and retain women and underrepresented minorities into technical fields; the ESA and Sony have focused their efforts specifically on gaming. Summer camps and programs like Black Girls Code, where girls code together, correlate to more of those girls choosing a technical track at university.

Provide Mentorship

Training more women for careers in the gaming industry and supporting those women as they pursue those careers is absolutely vital. The financial support scholarship programs provide is great, but personal and professional support is equally essential.

The #1reasonwhy tag we discussed in our last column has generated some great responses from individuals, including the #1ReasonMentors list (http://storify.com/pixelsprite/1reasonwhy-mentors-resource), which includes professionals willing to mentor women interested in working in the game industry. Organizations like Women in Games International (www.womeningamesinternational.org/) also help build a community of women game industry professionals.

Recruit a Critical Mass of Women into the Industry

Game development is a young man’s game. And we mean that quite literally. An old timer in the development field is in his early forties. In her paper “Forces in Play: The Business and Culture of Videogame Production,” Robin Potanin notes that computer game development is a bastion of machismo in which young men, often in their twenties and thirties, slave to create the games they want to play.2 This leads to the “I” Methodology, with the games themselves reflecting the lives of their creators. Such a method of creation perpetuates the problems that we discuss—men create what they want to play, other people play it, other young men are inspired because it reflects their values, those men enter the industry. We do not merely need to help women get into the gaming industry. We need to help a lot of women enter the industry.

There is a notion of critical mass often invoked when discussing the importance of recruiting and retaining women in technical fields; the idea is that once there is a certain number of women at a lab, a company, or other organization, other women will be more interested in working in that environment and the organization will become more welcoming to women. Gaming clearly has a critical mass at the level of play; this doesn’t mean women players are treated equally, but it does mean that there is no time like the present for gaming culture to change. At the production level, the industry needs a harder push. While the efforts of the ESA and Sony to train and retain women game developers are heartening, those efforts will not be enough if those same women enter openly hostile work environments or face some kind of pixelated glass ceiling as they work to level up in their careers.

Image Credits:

1. Brenda Romero’s #1reasonwhy resignation announcement on Twitter

2. Still of Sarkeesian’s Tropes vs. Women

Please feel free to comment.

- Kaplan, E. Ann, Rocking Around the Clock: Music Television, Post Modernism, and Consumer Culture (London: Routledge, 1987). [↩]

- Potanin, Robin. “Forces in Play: The Business and Culture of Video Game Production.” Fun and Games ’10 Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Fun and Games, Leuven, Belgium (Sept. 2010): 135-43. [↩]

All great points.

I would add one: Economics. That’s why EA will not stop being a shitty company and fix the new Simcity as long as we pay for it. They are not beholden to morals but to their shareholders.

Well, in the same vein, if I’m a company I would love to have the women demographic as my clientele? I’d have female avatars so that women are more likely to play and don’t turn it into the whole “Let the male audience choose their ideal-hot-women as the female avatar” like the Mass Effect 3 debacle. I feel like that’s how the movie industry evolved – “Holy shit, %50 of the Dark Knight audience is women?!” – and that’s how we shall have more of an equality in the gaming world. I’d say there has been a considerable improvement by the way; the Mass Effect 3 debacle was averted by a swift stroke and the new Tomb Raider – from what I’ve seen – seems like a colossal improvement over the prior “Male Fantasy sex-bot with breasts like a bazooka”.

Overall; I think appealing to companies and making sure that the demand is there would be a huge step.

Thanks for the article.

I definitely agree with Omer on the point of the Dark Knight as a point of comparison. I think TV and Film (though certainly not examples of great female representation in company leadership roles according to a study last fall) are coming around to the idea that fangirls are a bigger demographic than they realized and maybe they should keep that in mind when creating content. Gaming is not there yet, and I think it’ll probably take another decade of female gamers and game developers really breaking into the industry to kind of alter how the industry works.

Realizing you have female gamers and developing the right content for them are two different things. Too often I think male developers might try to guess what female gamers want, and the result can be patronizing. The author is right that the best way to figure out what they want is just bring in more female game designers. The answer will probably surprise them.

I saw this related article yesterday. While I suppose the author tries to couch his comments with calls for more realistic depictions of women in games, I feel like the dismissive attitude towards whether you would want to play this game in front of friends is missing the point. I’d be embarrassed to play that game by myself. I’m a red-blooded male gaming fan, and I get annoyed when I feel like the gaming industry thinks so little of me that they think a sophomoric sexual depiction will win my dollars. It’s not just that I think the gaming industry doesn’t understand it has female audiences, I don’t think they understand that their male fan base doesn’t just consist of 14-year-olds anymore.