Iconic Television and Pathos

Gerald R. Butters, Jr./Aurora University

From the 1950’s through the 1980’s, the medium of television created a number of iconic moments. I define “iconic moment” as a piece of entertainment or historical event that was shared by a large mass of the American public. Specifically, in this time period, it included the birth of Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz’s baby on I Love Lucy (1952), the exoneration of Richard Kimble in the final episode of The Fugitive (1967), the “Who Shot JR?” episode of Dallas (1980) and the series finale of M.A.S.H. (1983).

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=F83m6HaYWIg[/youtube]

All of these events were pieces of television entertainment, significant enough that they were watched by tens of millions of Americans and the majority of the television viewing audience. But iconic television moments of this era also included television coverage of significant historical events including the Kennedy-Nixon television debates (1960), Neil Armstrong walking on the moon (1969), Richard Nixon’s resignation speech (1974) and the explosion of the Challenger (1986).

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j4JOjcDFtBE[/youtube]

These were shared historical moments that were intensified by the medium of television both with the immediate coverage of these events and then with the saturation follow up in their depiction.

Television, in its first thirty years, was a medium almost unrecognizable to today’s generation of youth. In most markets, including major urban areas, television viewers had three or four choices when the television was turned on. The major networks – NBC, CBS and ABC – each had their own channel in major markets. There also was often a UHF station and after 1969, a PBS affiliate. But this only applied to major markets. Rural areas often had even more limited viewing opportunities. Nevertheless, from the 1950’s through the 1970’s, Americans had far more commonalities in their viewing patterns due to the limited number of choices. Whether one was discussing Perry Mason, Archie Bunker, The Fonz or the Clampetts, there was a cultural televisual literacy that the majority of Americans shared.

The medium of television began changing with the introduction of cable television nationally in the 1970’s. By the end of the decade, nearly 16 million households were cable subscribers. Cable television often appealed directly to adult television viewers though. The lack of FCC regulation on cable networks such as HBO and Cinemax allowed the networks to feature more adult entertainment. The advent of the VCR in the early 1980’s and the explosion of videotape rental businesses gave Americans more of a choice when it came to their home entertainment decisions. By the 1980’s, Americans were no longer solely dependent upon the major networks; cable television and videotapes offered a multitude of entertainment possibilities. This began to have a precipitous impact on network affiliate viewing. In 1985-1986, 45.1% of U.S. households were tuned into the major networks on a nightly basis. In the 1980’s, there were still television shows such as The Cosby Show, Family Ties, and Cheers that had mass audiences though. By 2000-2001, the network share had dropped from 45.1% to 32.6%, a 28% drop. The winner for the viewing audience was basic cable which saw its share go from 3.9% in 1985-1986 to 28.2% in 2000-2011. This was a 1382% increase. Even more important, basic cable was almost claiming as many viewers on a nightly basis as network television. The number of choices in basic cable also exploded in the 1980s and 1990’s with channels devoted to home shopping, history, sports, news, children’s programming and home design.1 This meant that Americans were far more fractured in their viewing patterns.

The concept of the mass audience for a televisual entertainment event collapsed with the new century. The first major American reality television show, Survivor Borneo, captured over 51 million viewers in the season finale on August 23, 2000.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=n5M_H56CHgE[/youtube]

The behemoth that is American Idol had its first finale on September 4, 2002. Twenty-three million Americans watched Kelly Clarkson crowned as champion. But that was less than half of the mass audience for Survivor. For the first twelve years of this century, no American television event that is considered entertainment has captured a mass audience. Only 25% of the viewing public still watch a network channel on any given night. Sporting events, primarily the Superbowl, are still able to capture huge audiences but no fictional or reality television show can claim these ratings.

Does this mean that Americans no longer share iconic television moments in our culture? Well, we do, but they are coverage of historical events. And almost all of these events have been significant tragedies. The horror of the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001, the sheer destruction of Hurricane Katrina in 2005 and the recent massacre at Sandy Hook Elementary school (2012) all were tragedies which were covered intensely by network and cable news teams, watched by tens of millions of American viewers.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q_8zXJcoxHY [/youtube]

What does this mean for our culture when the only shared events we have are tragedies; television accounts of suffering and pathos? What does this mean for the medium of television as a cultural force in our nation? If the only shared moments that television can bring to the American people are tremendous losses of human life, inhumanity, violence and terror, what does this say about the future of the television medium? As an “imagined community” are we united only by our sharing of grief, anxiety and tears?

Since its inception, television, as an artistic form, has rested on its appeal to the audience’s emotions. Those singular iconic television moments that resounded throughout our culture were often dependent upon universal human events (births, marriages, deaths) or finales which masses of people could relate to. Now that the American television audience is fractured into millions of individual components, with individuals not only viewing hundreds of different television channels but also watching television when they desire, be it streaming, on demand, on the internet or on DVD, the singular iconic television moment in the form of entertainment, ceases to exist. So all we have, as a shared community, are historical incidents of deep pathos. If the only iconic television moments we share are depictions of suffering, does this reflect the deep cultural and political divides in our nation? Victories, be they political or judicial, are not shared by an American people deeply fractured.

The one unique exception to this model was the 2012 London Olympics. Prior to the summer of 2012, many cultural commentators believed that the Olympics were passé, a relic of the twentieth century. Yet more than 219.4 million Americans watched the Olympics, making it the most watched event in U.S. television history. NBC’s coverage of the Olympics was wildly castigated by the critics as human interest stories (rather than sport) seemed to construct the coverage and that the network almost exclusively focused on American athletes. Yet this combination of Lifetime/Hallmark emotion and rampant nationalism played well with the American people, with over 31 million Americans watching the coverage every viewing night. Perhaps this sharing of a sporting event, draped in melodramatic emotion and patriotism, supplanted the relentless parade of tragedy on television.2 This relationship between a mass medium, iconic shared moments, and national identity, in the twenty-first century, is ripe for exploration. The old models no longer apply.

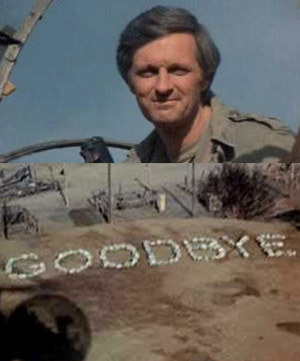

Image Credits:

1. Final Moments of MASH

Please feel free to comment.

- Bill Gorman, Where Did the Primetime Broadcast Television Audience Go? TV By the Numbers http://tvbythenumbers.zap2it.com/2010/04/12/where-did-the-primetime-broadcast-tv-audience-go/47976/ [↩]

- London Olympic 2012 Ratings: Most Watched Event in TV History, http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2012/08/13/london-olympics-2012-ratings-most-watched-ever_n_1774032.html [↩]

It is indeed a morbid thought that the most prominent iconic moments on contemporary television are tragedies on the news such as terrorist attacks and natural disasters. That is, as you stated, with the exception of the Olympics, and sporting events like the Superbowl. In response to your question, “are we united only by our sharing of grief, anxiety and tears?” I want to believe the answer is no. I agree there has been a clear decrease in iconic moments for televisual entertainment – the simultaneous viewing of a live television program – but is there any accurate way to gauge the overall viewing of that moment/program over time? I understand this doesn’t meet your definition for the old standard “iconic moment” but maybe these new times deserve a new way for defining the iconic moments that are happening on an entertainment level. In the end, is there a real difference between 10 million people watching Lucy and Desi have a baby at the same exact minute versus over a week? The current TV audience wants to watch “their” entertainment when they want to and are able to. When tragic events or sporting events happen there is a different sense of immediacy to be involved, to stop the usual routine to be in “the know.”

The silver lining is perhaps the public is not being distracted from the world by television anymore, but rather they are now engaging with the world through television. Whereas the aforementioned “iconic moments” of the 50s and 60s were all of significance with respect to their entertainment value, the new “iconic tragedies” of the 21st Century are of historical significance. America’s reaction to the Sandy Hook shooting is going to cause gun reform. Hurricane Katrina convinced many that they could not rely on the government for their safety during a natural disaster. And there’s no need to even begin to scrape the surface of how the 9/11 attacks changed our perception. The country may not have been able to sit in awe together for the finale of Lost or when Ed Stark gets decapitated on Game of Thrones, but they are able to do so for the moments that will matter 100 years from now.

First of all, I want to say that the shifts in television both structurally and technologically have come from a mass cultural desire for change. The formation of todays more individualized TV experience is a direct result of cultural need. TV has always been defined as culturally specific and temporally limited. It is an ever-developing genre, and therefore changes in the medium are a direct reflection on society. We may no longer share iconic TV moments in the same way as people did in the 1950s, but we also don’t share the same notions of female empowerment or racial segregation. Times have changed; society in relation to most everything has progressed. I think it’s ridiculous to say that the modern “imagined community” that is created through the shared experience of the audience is united only in grief. This is simply untrue. We may no longer share moments of entertainment or history at one concrete hour, but I would argue that entertainment is more widely shared and more far reaching today than ever before. The over flow of TV onto the Internet has increased our ability to interact with television shows and fans. Social media sites have allowed for fans from all over the world to discuss and share TV moments like never before. Even in 2001, this shift in mass consumption and flow of TV content was clear, as outlined in Will Brooker’s article “Living on Dawson’s creek”. Brooker sates: “The [TV] structures are there to enable an immersive, participatory engagement with the programme that crosses multiple media platforms and invites active contribution; not only from fans, who after all have been engaged in participatory culture around their favored texts for decades, but also as part of the regular, ‘mainstream’ viewing experience. [TV Shifts] will happen, increasingly, and we will need new terms to discuss the shifting nature of the television audience. The concept of overflow helps to establish this new vocabulary.” The viewing experience has changed; the audience is no longer confined to the living room or limited to the network’s schedule. This freedom has allowed for programs and TV moments to be shared over and over again around the world, creating a global community united through the TV medium.

A common phrase you will hear in writing classes is, “Universality through specificity.” The world of Lena Dunham’s GIRLS is populated specifically by white, upper or upper middle class 20-something females, and through its specificity it is universal.

I agree with your statement that “it is within that context that we may or perhaps must assess the show. The posture, the problems, the values, the politics, the angst… all steeped in whiteness.” Yet I also have issues with the idea of a character as “representative of his race.” Watching a television show might give an audience insight into the culture of the race of the characters that appear on screen, but the show never sets out to paint a picture of a race. The race of a character should instead be considered just another piece of the social and historical context in which they operate.

Also the argument that the “inability or unwillingness of many White people to think of themselves in racial terms has decidedly negative consequences…[and] produces huge blind spots,” fails to get to the root of why this is. Race is such an ambiguous and ill-defined concept that it is no wonder White people have a problem identifying themselves in racial terms. Many White people Will self-identify as White, but there is little cohesion of identity within the White population of the world. White people are in fact very diverse, and tend to place more emphasis on cultural heritage than racial heritage. Caucasian Turks and Italian-Americans are both white, but they will not naturally group themselves together.

While the concepts coined by such terms as “iconic moments” and “mass audience” are, as you stated, decreasing in numbers contemporarily, does the fact that the very nature of television as a medium has been evolving not demand that the concepts behind these terms evolve as well?

Even though recently most of the “iconic moments” as shared by “mass audience”, meaning nationally, have been tragedies, how can we disregard the each individual little moments as shared by audiences around the country as not a mass but as groups, people who share the same interests, have the same “niche”, or are within the same aesthetic community? Do these moments not add up to a more positive effect as it allows greater flexibility in individuality, given the massive selection of channels and shows?

In fact, what does “mass audience” as bringing together a nation even mean? How does a nation become brought together? Is this a result of a massive number of people watching the same show, obtaining the same information, and somehow are able to form a collective consciousness? Why can’t people choose to form this collective consciousness with people who are more proximate with them in terms of viewing choices? In the 50’s and 60’s, the limitation in numbers of networks forced forming of “mass audience” but cannot ensure that everyone who tunes in is by choice. It may be simply from a lack of choice.

Is the fact that the audience no longer are forced into big clumps of uniform preference but instead have the choice to customize what they view not something to be happy about? Does this not signify the fact that as individuals of a larger group (such as the nation), people have gained the relative freewill of commercial intake not a triumph?

The idea of iconic moments in television still exist but in a different way. I don’t think it means that our culture is morbid when the only shared events we have are tragedies. There is so much more opportunity for customizing entertainment consumption today Its not surprising that the nation now only unites en mass to watch tragedies on the news such as terrorist attacks and natural disasters. Its not surprising because these events are day and date specific, and to stay informed and current on the situation you need to watch at a certain time. The way we consume entertainment and watch television has changed drastically since the days of “I Love Lucy” and “MASH,” now we can watch whenever/wherever we want. The new “iconic” moments are newsworthy because if we miss watching them at the precise moment they air then we miss out, just like tuning in to watch Lucy give birth or the series finale of MASH was back in the day.

I still think that Americans connect over television moments but just on a different scale than before. Audiences are so segmented now and individualized that I think it would be impossible to share an “iconic” moment in television on the same scale that is being compared. For example for the fans of Portlandia, there are many iconic moments in that show but those don’t translate universally because the show is not targeted for a mass appeal, it has a niche audience which I think is the case for most contemporary television. We need to rethink the concept of inconic tv moments in a way that makes sense for the ever evolving medium of television.

he is so cute