Mobile Mediality II: Locative Mobile Gaming

Mimi Sheller, Drexel University

While mobile art tends to heighten one’s experience of place or embodied sensory perception, LMG is oriented more towards sheer enjoyment of a new kind of hypermediated space through play. Yet it also has implications for the wider production of “augmented” urban space and “net-locality”1, because it draws on location-aware and proximity-aware capacities that are gradually extending into more and more everyday activities. Basic forms of LMG begin with “collecting games” within mobile locative social networks such as SCVNGR, a game “about doing challenges in places”, or Foursquare, in which participants collect “badges” and compete for “mayorships” by checking into particular locations. But it extends towards more complex gaming interfaces that involve multiple players interacting through avatars, game actions, and game screens, as they move through physical space, collecting virtual objects but also potentially generating other kinds of social interactions23. Mixed Reality (MR) gaming combines virtual data with physical locations, generating an immersive and interactive real-time environment, with the potential for narrative and creative story-telling (such as cinema) to take new social and spatial forms.

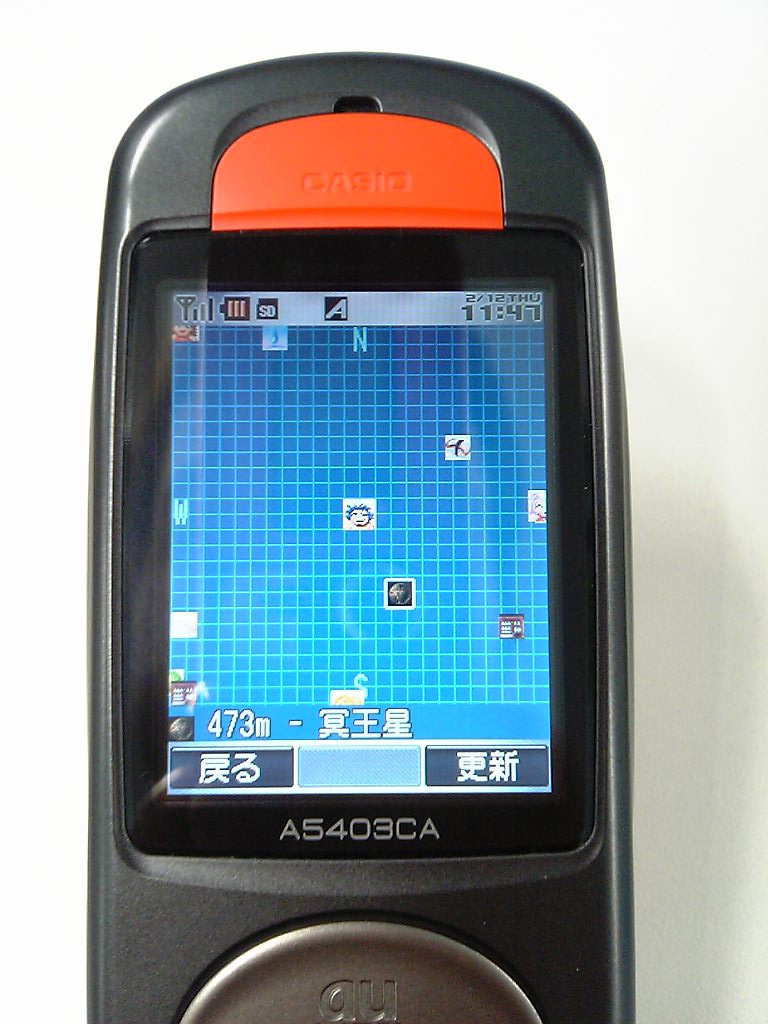

Such mobile locative games first became popular in Japan, beginning with the socially connected mobile roaming game Mogi (Newt Games, Paris, 2003), followed by games like Colonial Living PLUS (Colopl Inc., 2005). As early players enthused, these games hinted at an emerging mixed reality future: “Giving people the tools to play together in the city: Mogi is a brilliant, obvious envisioning of location-based gaming. Mobile multiplayer the way it was meant to be, providing a data layer players can affect and participate in together, as they inhabit the real world. Today on the streets of Tokyo, Mogi is a shimmering glimpse of what is to come – real and virtual coming in direct physical contact through us the players.”4

In locative mobile gaming, the game world is notionally superimposed onto the city’s surface, and the game narrative can influence the players’ movement within the city5, understood now as a “networked place”6. Even in its most rudimentary forms, a transformative potential was sensed. Mobile locative games create a social world that encompasses the vicinity of the players, while the players’ spatial practice forms the conditions for progress within the game narrative. Thus they give new meanings to the players’ physical location, by lending it a mediated resonance as part of the game-play.

Locative mobile gaming can combine analog and digital concepts of play, as well as links between a computer-based interface and phone-based interface. For example, “Rider Spoke” (2007) is a mobile game for urban cyclists, designed by the British collective, Blast Theory, which combines theater with cycling and mobile game play in a public urban environment. Their ideas of immersive theater were developed further in another hybrid mobile gaming project, “You Get Me” (2008), and later “I’d Hide You” (2012) launched at the FutureEverything Festival 2012 in Manchester. Participants logged in online to join runners on the streets of Manchester, seeing the world through their live-streamed video headsets, and interacting and directing the runners as they played a game of team tag7.

I’d Hide You from Blast Theory on Vimeo.

Studies of mobile gaming raise crucial questions about how such mobile mediality potentially blurs, undermines, or transforms privacy, publics, place-making and social connections. Some critics charge that many forms of “gamification” are simply a commercialization of mobile social networks (used to promote products or nearby places through free offers and e-coupons). Problems with stalking and concerns over locational privacy have emerged in some gaming contexts8. Others feel that such games may potentially promote a technological apparatus of surveillance that “intersects with corporate and military interests.”910

Augmented reality applications will become increasingly important in the production of new mobile games. Smartphones have already brought applications like Junaio and Layar into common use, with digital pop-up ads and mobile augmented reality [AR] covers appearing on magazines (e.g.,Time Out New York Kids, Esquire, Popular Science) and 3-D displays in catalogues (e.g., IKEA 2013). Mobile locative apps are beginning to flourish with AR data displays promising to guide us to coffee shops and subway stops, reveal historical photographs and lost buildings, star gaze and navigate mountainous terrain, not to mention shoot baskets and fight aliens. Locational 3-D simulations are making their way into architectural practice, design charrettes, and urban planning. And mobile AR games are starting to appear that engage players with virtual objects and networked players embedded into their physical surroundings11.

In 2013 such applications will be improving their capabilities by incorporating new motion-detection and proximity sensors. Start-up companies are jumping into the market, pulling data from the cloud and ever more tightly coupling it with geo-spatial locations. New platforms are also emerging. TIME magazine declared Google’s Project Glass the best invention of 2012 because “it’s the device that will make augmented reality part of our daily lives,” although not until it debuts on the market in 2014. It will certainly be of great interest to game designers and players. And car makers like Mercedes-Benz were showing off their plans for augmented-reality and gesture-controlled features on car windshields at the 2012 International Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas, with even more new AR platforms in store for 2013. Will cars be the next platform for AR and MR gaming?

In contrast to these commercial trends and worries about the social impacts of mobile gaming, we might instead ask whether it is possible to build vibrant games that use mobile, geo-located, and/or augmented reality experiences for more positive, or at least thoughtful, forms of interaction with place, locality, and public engagement. As noted in the previous column on Mobile Mediality, many artists are already experimenting with these potentials. We can envision ways in which mobile locative gaming might extend and build on the following activities, which are more akin to “serendipitous play” than more commercial types of “gamification”:

Urban annotation and gleaning

Situated interactive oral history

Soundscapes and acoustic walks

Public mobile art projects as mixed reality immersion

Location-based social networking games for civic engagement

Grassroots mapping and open data participatory games

Digital sharing economies and convivial spaces

Because mobile locative gaming offers new ways for mobile connectivity to be drawn into gaming activity, it can be considered as a form of “remediation” of gaming in which “the real is no longer that which is free from mediation, but that which is thoroughly enmeshed with networks of social, technical, aesthetic, political, cultural, or economic mediation”12. In that regard, there is a drive to produce alternative practices of mobile mediality, some of which are pushing towards the commercialization of mobile gaming, but others are aiming to create more disruptive spaces of resistance, of sharing, and of convivial mobile publics. I will explore these possibilities further in the final column on mobile mediality.

Image Credits:

1. Early Locative Mobile Game, played in Japan: Mogi (Newt Games, Paris, 2003)

2. An early MLG: Japan’s Colonial Living PLUS (Colopl Inc., 2005)

3. Mogi – “Players can see on their mobile phones a map of Tokyo showing the location of hidden items, as well as other players.” Courtesy of Paul Baron

4. Google Project Glass

Please feel free to comment.

- Gordon, E. and de Souza e Silva, A. (2011) Net Locality: Why location matters in a networked world, Boston: Blackwell Publishers. [↩]

- Licoppe, C. and Inada, Y. (2006) “Emergent Uses Of A Multiplayer Location-Aware Mobile Game: The Interactional Consequences Of Mediated Encounters”, Mobilities 1(1): pp. 39-61 [↩]

- Licoppe, C. and Inada, Y. (2009) “Mediated Proximity and Its Dangers in A Location-Aware Community: A Case Of ‘Stalking”, in A. de Souza e Silva, & D. M. Sutko (Eds.) Digital Cityscapes: Merging Digital and Urban Playspaces, pp. 100-128 (New York: Peter Lang) [↩]

- http://thefeaturearchives.com/100501.html, 01 April 2004, accessed 04 January 2013 [↩]

- Drakopoulou, Sophia (2010) A Moment of Experimentation: Spatial Practice and Representation of Space as Narrative Elements in Location-based Games. Aether: Journal of Media Geography, 5A: 63-76. [↩]

- Varnelis, K. and Friedberg, A. (2006) “Place: Networked Place”, in Networked Publics (MIT Press), Accessed 10 October 2010 at: http://networkedpublics.org/book/place [↩]

- http://vimeo.com/48141546 [↩]

- Licoppe, C. and Inada, Y. (2009) “Mediated Proximity and Its Dangers in A Location-Aware

Community: A Case Of ‘Stalking”, in A. de Souza e Silva, & D. M. Sutko (Eds.) Digital Cityscapes: Merging Digital and Urban Playspaces, pp. 100-128 (New York: Peter Lang). [↩] - Farman, Jason (2012) Mobile Interface Theory: Embodied Space and Locative Media, London and New York: Routledge [↩]

- Tuters, M. and Varnelis, K. (2006) “Beyond Locative Media: Giving shape to the internet of things”, in Networked Publics (MIT Press). Accessed 10 October 2010 at http://networkedpublics.org/locative_media/beyond_locative_media [↩]

- De Souza e Silva, Adriana and Sutko, Daniel M. (eds.) (2009), Digital Cityscapes: Merging Digital and Urban Playspaces (New York: Peter Lang). [↩]

- Grusin, Robert (2010) Premediation: Affect and Mediality after 9/11. Houndmills and New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [↩]

So we have got this thing which is very useful for us so that we can generate the madden coins.