Lindsay Lohan: Star Image Succubus

Andrew Scahill / George Mason University

At this point, stories of Lindsay Lohan’s tumultuous personal and professional life are legion—enough to warrant a timeline of legal woes. They show no sign of abetting, either, as a recent New York Times article entitled “Here’s What Happens When You Cast Lindsay Lohan in Your Movie” chronicles a nightmare scenario of unprofessionalism, melodrama, and ego.

Indeed, stories of her “troubledness,” be it her diva behavior on set, alcohol and drug abuse, frequent trips to rehab, driving under the influence, grand theft, or violating parole after many of these actions, have largely eclipsed the narrative of Lindsay Lohan as a promising young starlet. The new narrative is a familiar one in our construction of the “child star”: squandered talent, Hollywood excess, selfish parents, corrupted innocence, and spiraling addiction. In effect, Lohan’s celebrity image has become her star image—and any role she now undertakes must be presented not despite that image, but through and because of it. Her recent engagements with the star images of Marilyn Monroe and Elizabeth Taylor witness an attempt to accommodate her troubledness within a larger and more prestigious narrative of female stardom and celebrity.

A Star is Reborn

“Stars are actors ‘with biographies’” writes Robert C. Allen in Film History: Theory and Practice.1 This simple definition draws upon Richard Dyer’s assertion that the star is a “structured polysemy” in which multiple meanings and contradictions coexist in the body of the actor through her/his performances, publicity, and celebrity life. John Ellis has referred to stardom as a feedback loop in which performances, celebrity, and audience interpretation continually recapitulate the star’s image, which in turn controls the modes through which the star engages with the public to manufacture meaning. Ellis goes on to claim that the star image is perpetually unstructured—that the promise of cinema is redress incoherencies and to provide a “true” understanding of the star.2

Finally, and perhaps most usefully for examining Lindsay Lohan, Christine Geraghty has argued in “Re-Examining Stardom: Questions of Texts, Bodies, and Performance” that we must unpack the various categories of star to understand “the different ways in which well-known individuals ‘appear’ in the media [and to] understand what film stars have in common and how they differ from other mass media figures.”3 She argues for three categories: “star-as-professional,” whose stable star image makes them a certain type (Stallone, for example), “star-as-performer,” known for their method performance (DeNiro, Streep), and “star-as-celebrity,” known largely for their off-screen personas.

Frequently (at least frequently enough to take note), Lohan’s touted “return” to acting or non-celebrity forms of fame occurs by invoking beloved former female stars. Indeed, Lohan depends of upon the semiotic utility of these stars as not simply “troubled,” but “troubled, AND YET…” By tapping into the semiotic value of Monroe and Taylor, Lohan and her handlers seek to place her within a pantheon of female stars whose troubled celebrity lives stand as evidence of their genius, and where words like “spoiled,” “entitled,” or “addict” can be replaced by “fiery,” “passionate,” or “misunderstood.”

Lindsay Lohan as Marilyn Monroe

Lohan has taken three turns at reproducing the iconic bombshell, first in 2008 when Bert Stern chose Lohan to reproduce his iconic 1962 photos of Monroe for New York Magazine. The original session, just six weeks before Monroe’s barbituate overdose, is often referred to as “The Last Sitting.” Hazy and dreamlike, the original photos suggest an intimate and private experience with Monroe. In the context of her death, the photos take on an ethereal quality—ghostly, or at least angelic—as most of the public would not see them until after her death.

One wonders at the thought process of Lohan, a frequent rehab clinic guest, to reproduce these memento mori photos of Monroe at her most troubled moment. Asks Amanda Fortini of New York Magazine, “…one wonders whether Lohan’s participation in this project, given all the spooky parallels, isn’t the photographic equivalent of moving into a haunted house. (Which, in fact, she may have already done.)”4

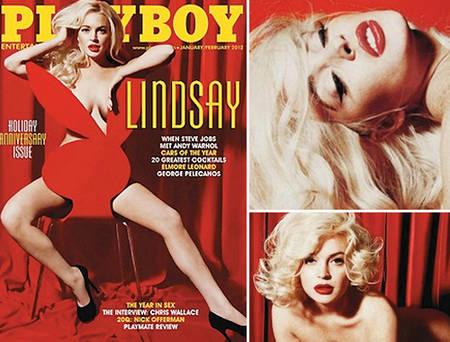

Lohan would return to mimicking Monroe in 2012 by reproducing the star’s centerfold spread for Playboy magazine in 1953. It’s worth noting the trajectory of these reiterations—first at the end of Monroe’s career, then at the early stages… from haziness to freshness and vitality, or—if you choose—from death to life. Ironically, associations with Monroe’s death continued despite this context as the photo spread marked the 50th anniversary of Monroe’s death.

Another iteration of Monroe’s image will occur in 2013 as Lohan uses an avatar for revenge against the paparazzi. She can be seen in this (nearly unwatchable) trailer for InAPPropriate Comedy reproducing Monroe’s famous scene from The Seven Year Itch and then gunning down photographers who take her photo.

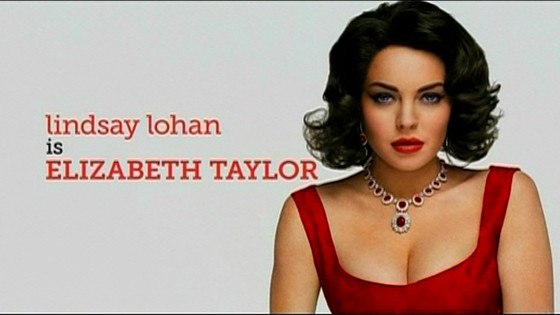

Lindsay Lohan as Elizabeth Taylor

The promotion for Liz & Dick was essentially two-fold, both features entirely reliant upon Lohan’s celebrity image. First was anticipation (rightfully) that the media would discuss at length the “train wreck” potential of the film. Indeed, both mainstream and gossip outlets balked at Lohan’s casting, and much of the draw of the film seemed to be its potential for spectacular failure. Stories of Lohan’s on-set antics—including a paramedic visit and car crash—did nothing but fuel these expectations.

This was played out, for the most part, as the media summarily panned the film for writing and performances. Claiming that the film was tailor-made for drinking games, Tim Goodman at The Hollywood Reporter called it “an instant classic of unintentional hilarity.”5

The second mode of promotion was to subsume Elizabeth Taylor completely and to promise the spectator a film about Lindsay Lohan as her star-as-celebrity persona overrules her performance. This recalls Ellis’s suggestion that cinema is a forever unfulfilled promise to finally reveal, in toto, the full star.

The litany of phrases on the poster reference Taylor, certainly, but are there most potently to address Lohan’s persona. Phrases like “PAPARAZZI,” “TABLOID FRONT PAGE,” “SCANDAL,” and “CHILD STAR” seem more directed at Lohan, especially as the film itself makes no mention of Taylor’s early career as a child actress. “DIAMONDS” becomes almost parodic in light of Lohan’s frequent bouts with jewelry theft.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lCNFGJWNjZs&feature=youtu.be[/youtube]

In a behind-the-scenes promotional clip, Lohan describes herself as a huge Elizabeth Taylor fan, and details their similarities, including “living in the public eye” and “dealing with the stress of what people say.” Costar Grant Bowler even goes so far as to call Lohan “pretty much Elizabeth Taylor, reincarnated.”

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mV8lzhW-qMM&feature=youtu.be[/youtube]

The media, too, touted the similarities, often talking as if the film were a biopic about Lohan rather than Taylor. In a November appearance on Good Morning America, the interviewer says, “Liz Taylor’s life was out of control at times, and to be honest, so has yours. From the moment you step out of your house there is often times drama, there has been legal troubles.” Lohan later discusses her performance, saying that one “can never you be, y’know, a clone of the person, so you have to bring some of yourself into it, and [I] relate to Elizabeth Taylor in a lot of ways.”

Certainly Lohan feels some sort of commonality with these former stars, but her actions seem to suggest that something more is at play here. The young actress seems to also trounce the boundary between fan and actress by engaging in mimicry behavior6 which reproduces the semiotically fertile exterior image of the stars without attempting to inhabit their personas. In essence, Taylor (and Monroe before her) become conduits for Lohan to navigate and attempt alter her own star image within the Hollywood system.

Image Credits:

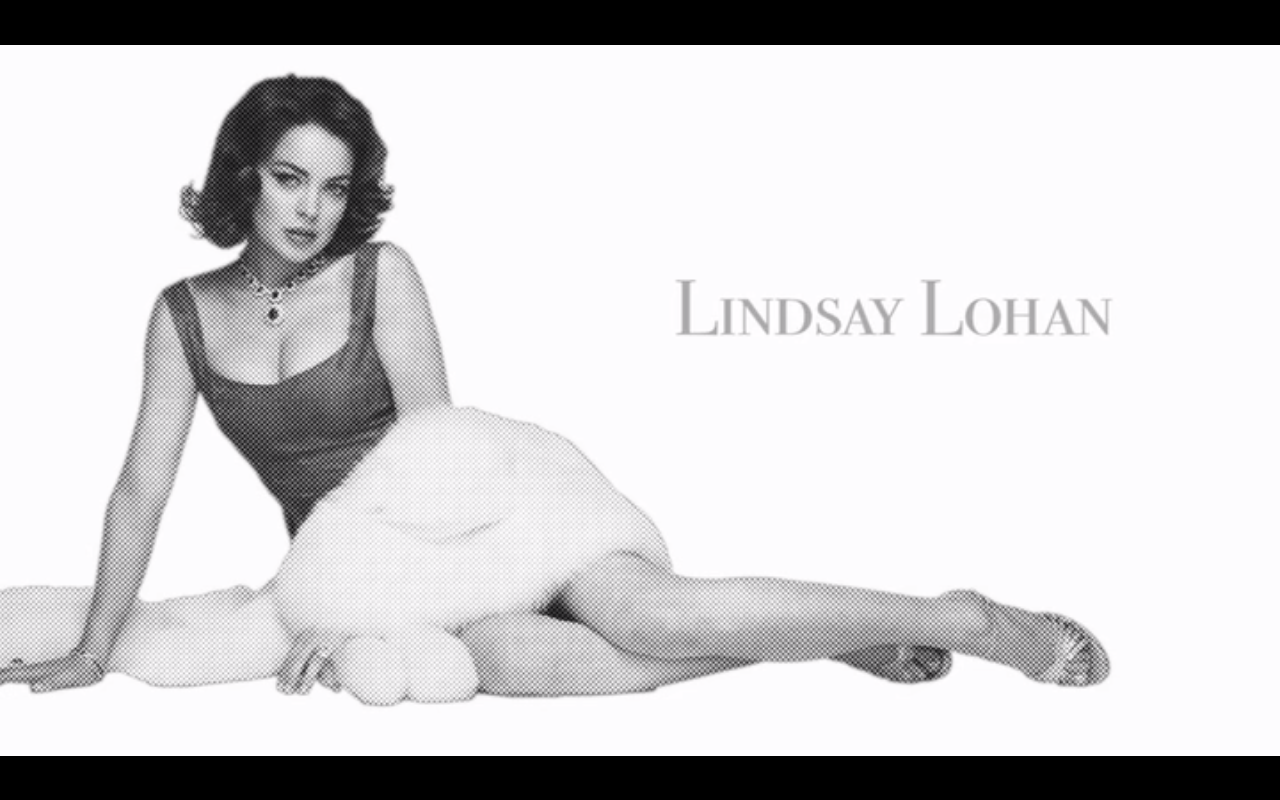

1. Lohan as Taylor presented as a photo effect of newsprint (Author’s screengrab)

2. Lohan in a side-by-side comparison

3. The cover and select cropped photos from Playboy

4. Lohan in InAPPropriate Comedy

5. Lohan as Taylor

6. Taylor in later life (Author’s screengrab)

7. Lifetime‘s poster for Liz & Dick

Please feel free to comment.

- Robert C Allen, “The Role of the Star in Film History,” Film History: Theory and Practice. NY: McGraw Hill, 1985. [↩]

- John Ellis, Visible Fictions. NY: Routledge & Kegan Paul, Ltd. 1982. [↩]

- Christine Geraghty, “Re-Examining Stardom: Questions of Texts, Bodies and Performance,” Reinventing Film Studies. Eds. Christine Gledhill and Linda Williams. London: Arnold Publishers, 2000. 187. [↩]

- Amanda Fortini, “Lindsay Lohan as Marilyn Monroe in ‘The Last Sitting’,” New York Magazine. http://nymag.com/fashion/08/spring/44247/ [↩]

- Tim Goodman, “Liz & Dick: TV Review.” The Hollywood Reporter. http://www.hollywoodreporter.com/review/lindsay-lohan-liz-dick-tv-391316 [↩]

- See Jackie Stacey’s Star Gazing: Hollywood Cinema and Female Spectatorship for an examination of female fan behavior, including imitation and copying. [↩]

Lindsay Lohan used to be so cute. So fresh-faced, so innocent. Now she’s a slow-moving train wreck that’s picking up speed. The only question is when and where that train is going to crash, and if the result will be catastrophic. In just a few short years, she’s gone from an adorable ‘tween movie star to a shell of a woman whose Wikipedia page features a long, four-paragraph section called “Car Accidents, DUIs and Rehabilitation.” That’s never a good sign. She’s withering away, both literally and otherwise. That fresh, innocent face is long gone, a pair of comically enhanced lips all that remains in its wake. The quintessential good girl-turned-Mean Girl-turned-bad girl, Lohan has become her generation’s poster child for regular arrests, embarassing drunken nights caught on film, shoplifting charges and a total career crash and burn. She’s had two DUIs, three trips rehab, and has been sentenced to 240 days in jail over four separate stints (although she’s only served a total of 15 days, plus 35 days of house arrest). Her most recent probation ended in March.

Right now, Lohan’s career prospects aren’t terribly promising. She’s signed up to appear in a new reality-TV show that will follow her terrible mother, Dina, and her siblings throughout whatever it is they do with their lives. She also will play adult film star Linda Lovelace in a new movie that has yet to start shooting.

Her clothing line 6126, which sells leggings and a few other questionable pieces, will debut a new collection shortly, and Lohan has been contemplating posing nude in the promotional materials. Items from the line, named after Marilyn Monroe’s birthday, retail for between $200 and $800. In a sad, if self-aware, development, Lohan is putting out a significantly cheaper line as well, called 7286: her birthday.

But who knows? This is Hollywood, and Lohan is ripe for a comeback. With a little luck and a little lenience from the judicial system, 7286 might just turn around and punch us all in the face.

Since I was born in 1990, I was fortunate to see Lindsay Lohan rise to fame with movies such as “The Parent Trap,””Freaky Friday,” and “Mean Girls.” She had so much potential and could have been truly great, had she considered a quieter, more conservative life, such as Hilary Duff; another child star. Often times, these starlets grow up in the spotlight, and aren’t aware of the real world around them, and that often times, their actions, will have consequences, despite their fame or fortunes.

In my opinion, the opportunity to portray the likes of Marilyn Monroe or Elizabeth Taylor, would be considered a great honor. These women changed history and their stories will never be forgotten. Through other articles I’ve read about the shooting of “Liz and Dick,” Lohan caused many problems and set-backs for the already lower budget biopic. These included car accidents, racking up ridiculous hotel bills, Partying all night with Lady Gaga, and missing call times. This technically “un-insurable” actress made a mockery of what should have been a masterpiece, outlining the life of a real troubled star.

Unfortunately, in this day and age, our culture spends an average of 34 hours a week watching television. The majority of this comes from adolescents who are still impressionable and look to celebrities for guidance and inspiration. More and more young stars are headed down paths that are destructive and create a bad influence for children to follow (prime examples are Amanda Bynes, Jodie Sweetin, and Macaulay Culkin). She went from a beautiful, bouncy red head with all the promise in the world, to a run-down addict that looks at least 10 years older than she really is. As a film studies major, Things such as this don’t go un-noticed and have become a hot topic for discussion. I am the eldest of 6, and television is most definitely not what it was when I was a kid, and most certainly not what it was when my parent’s generations were kids. Lohan’s contributions to this problem have been staggering.

I truly hope that one day, Lohan will wake up and decide to turn her life around and be the person we all know she can. Everyone loses their way sometimes, but strength comes from accepting the things you can’t change and acting upon the ones you can. She could make a complete recovery with a little luck and a lot of self control

Since I am in my early 20’s, I was born at a time when Lindsay Lohan was the adorable little girl that mesmerized us in cute movies such as the “Parent Trap”. Now she is all grown up and going from rehab to facing jail time. We have watched her go from sweet and innocent to a train wreck. I believe the bulk of her problems stem from bad parenting. Parents of celebrity children become so engulfed with thier child’s fame that they lose sight of what’s important to teach your child. Without stable parenting it becomes easy for a child to lose sight of themselves. They then become more susceptible to things such as substance abuse, eating disorders, depression, and legal issues. Looking bask at her upbringing and her home life some might just feel sorry for her.

My hope is that since she is still young she will bounce back from all this. Having an opportunity to play roles such as Marilyn Monroe or Liz Taylor would surely help her get on the right track and hopefully get her life back in order.

Given the recent downhill spiral that Amanda Bynes seems to have embarked on, I found it fascinating that people writing about her always made a point to set her apart from Lindsay Lohan. Reading this, I feel like it hits on a key difference between Lindsay and these other starlets. You hit on this at the center of your argument. In building up her image, Lindsay and her team have done a remarkable job of aligning her with, as you put it quite well, “a pantheon of female stars whose troubled celebrity lives stand as evidence of their genius, and where words like “spoiled,” “entitled,” or “addict” can be replaced by “fiery,” “passionate,” or “misunderstood.” Whereas Amanda Bynes may seem off-the-rails in a really bizarre manner when she suddenly starts tweeting images that draw assumptions that she is trying to fashion herself into a living Barbie doll, Lindsay has had a kind of tragic vibe for me that I’m now realizing stems from all of the associations between her and Marilyn and Elizabeth in recent years. I’d also be interested to know if the choice to put her in retro/vintage personas, one that is rooted in old Hollywood glamour, might have something to do with this effect.

It is definitely an interesting method of rehabilitating one’s image without actually changing the behavior that caused it, feeding off of the sentimental value that comes with other troubled stars’ personas. It doesn’t seem like a particularly sustainable tactic, if it is being used as a deliberate, overarching strategy.

My bigger question whenever the issue of Lindsay Lohan’s troubles comes up is why the American public has felt some sort of ownership of Lindsay–and in general, of female stars (and more specifically their bodies) since the age of celebrity–from Marilyn Monroe to Elizabeth Taylor to Liza Minnelli to Oprah to Whitney Houston to Britney Spears, and now Lindsay Lohan. The list goes on and on. Everyone consistently comments on Lohan’s sweet, innocent appeal when she first started as a child actress and her blossoming into a promising young teenager, and how she has turned into a “train wreck” since then. Discussion of weight gain and loss, drug and alcohol abuse, rehab, depression, violence, etc plague the careers of these women much more harshly than it does their male contemporaries, and people speak about them, whether realizing it or not, in language that conveys some kind of ownership of female bodies.

This is not a new phenomenon, of course. “Submission” to or penetration of the male gaze–like in this article, Marilyn’s spread for Playboy and Lindsay’s recreation of it–lends itself to this idea of ownership. Which is not to place women at blame in the slightest–it is more to mention that men and women alike come to understand a female body as something to be stared at, something to appreciate, something to obsess over, and eventually, something to be controlled. This emerges when we speak about our disappointment in her, our expectations of her (offscreen especially), or like the article mentions, using words like “spoiled” and “entitled,” in ways that seem to be an effort to try and determine what decisions she should make based on this collective sense of ownership and fantasized female image developed by the public.

To whom does Lindsay owe the responsibility of being the most morally upright citizen? Why do stars like Richard Burton, Heath Ledger (rest his soul) or Charlie Sheen get a pass, even at times becoming celebrated for their “exciting” lifestyles, but we spend years and years analyzing, obsessing over and shaming troubled female stars? The complicated relationships between fandom, celebrity and gender/sexuality are at play whenever we have a discussion over someone like Lindsay Lohan, and undoubtedly the conversation centers around Lindsay’s “belonging” to us, as we’ve come to believe. And perhaps this unfair possession of Lindsay and her body is in fact contributing to her “downfall,” as it is, since she is the ultimate victim of it. Inspired by the now (in)famous words of Internet celebrity Chris Crocker, “LEAVE LINDSAY ALONE!” :)