Liberal Scribbles on my Newsfeed: Political Gestures on Social Media

Eve Ng / Five College Women’s Studies Research Center and the University of Massachusetts-Amherst

The Day After, 1

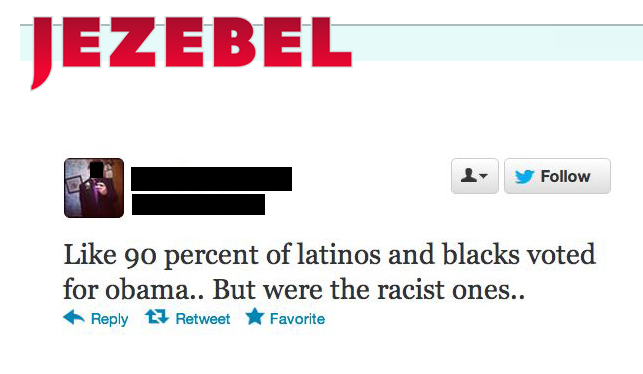

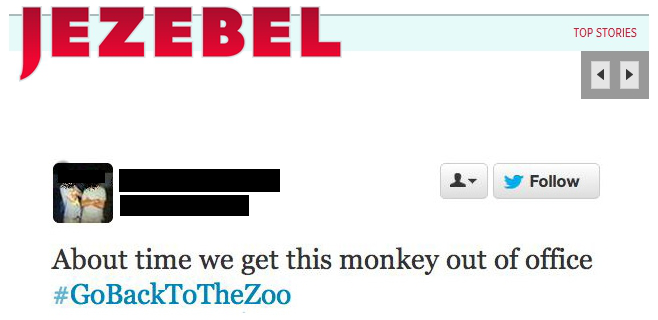

On November 7, the day after the U.S. elections, my Facebook newsfeed contained several links to Tracie Morrissey’s Jezebel article1 about tweets expressing blatantly racist disgust at President Obama’s victory. Many of these tweets, Morrissey noted, were posted by high school students, whose photos and names she did not obscure. Noting that some of them “have or are looking for sports scholarships for college,” she invited readers to “share these exceptionally racist remarks with their future schools.” Some readers questioned the ethics of identifying Twitter users who were minors and encouraging the possible derailment of their academic paths, while others argued that anyone posting such material publicly should be prepared to face the consequences. Asked about the issue by Forbes contributor Kashmir Hill, Jezebel editor Jessica Coen commented, “As soon as you are old enough to understand what you’re saying — and high school is definitely past that point — what you say online matters.”2 In a follow-up piece a couple of days later,3 Morrissey revealed that several of the Twitter accounts she had referenced had been shut down. However, all the tweets that had been screencapped in her earlier article are still available there, and will probably have an indefinite digital life elsewhere.

Flashback 1

The outrage in Morrissey’s pieces clearly resonated with many people, and reminded me of how, in July 2009, my Facebook newsfeed lit up with a chorus of condemnation as soon as the first reports came out about Harvard professor Henry Louis Gates, who is African American, being arrested outside his Cambridge house by a white police officer, James Crowley. The posts were annotated with comments assuming racial bias against Gates on Crowley’s part, and certainly, the posters were not alone; President Obama himself commented a few days after the incident that “there is a long history in this country of African-Americans and Latinos being stopped by law enforcement disproportionately. That’s just a fact,” while an email circulated by Crowley’s fellow Boston Police Department officer Justin Barrett describing Gates as a “jungle monkey” was a stark example of racism in the BPD. What struck me most about the response I saw on Facebook to Gates’ arrest was how readily some commentators jumped on this story, eagerly displaying their indignation.

The Day After, 2

Another item on my Facebook newsfeed on November 7, 2012, was the White People Mourning Romney tumblr site4 (hereafter abbreviated WPMR), which displays photos of disconsolate, (presumed) white supporters of the losing presidential candidate. One of the first items I saw there had been featured for an article for the UK’s Daily Mail, and showed a grey-haired couple sitting on a stack of flat cardboard boxes, the woman holding a blue and white “Romney: Believe in America” sign, the man with his hands resting below his belly. With his blue jeans and corporeality, the presentation of the man in particular seemed to signify a working class identity, with the composition as a whole decidedly heartland America.

Flashback 2

In this instance, I recalled learning about the People of Walmart website5 (PoW) a couple of years earlier also through a Facebook friend’s post. This site posts photos of Walmart customers deemed by contributors to be affronts to fashion, deportment, and fitness; displaying, in other words, the tastelessness and excess attributed to working class bodies. On PoW, then, the class-based judgments are rather obvious and consistent, particularly given Walmart’s association with a clientele attracted by inexpensive goods.

On first blush, it might seem strange to compare WPMR to PoW; after all, many of the images at WPMR show male Republican supporters in button-up shirts, ties and blazers and the smartly dressed equivalents for women, their class thus marked as middle and upper class. And given the plethora of election post-mortems identifying the GOP as being, among other things, too white, is WPMR not simply highlighting that position, albeit in an unabashedly gleeful manner? As conservative New York Times Ross Douthat columnist observed peevishly, “Winning an election doesn’t just offer the chance to govern the country. It offers a chance to feel morally and intellectually superior to the party you’ve just beaten.”6 However, WPMR should not simply be seen as equal opportunity class-wise in its “liberal gloat,” which would evade the inequalities of class positions. Whatever is problematic about a site containing images of sexually objectified women, for example, would not dissipate even if the site also included images of sexually objectified men.

As various people have noted, we produce online identities through social media sites like Facebook and Twitter (e.g. see boyd, 2006; Enli and Thumim, 2012; Livingstone, 20087). While profile summaries and photos may be the most obvious items involved, the links posted are not simply informational, but work like “likes” and other indicators of the poster’s positions on any number of topics. A link to Morrissey’s article, then, marks the poster as someone who also condemns racism. However, it is not only individual identities that are being produced; these posts can also collectively reinforce dominant discourses or encourage a pitchfork crowd mentality, even if the linked article offers valid critique or some insightful discussion.

The character of Facebook does not encourage link-vetting; like other social media sites, posts tend to be made and consumed at a rapid pace, and it is no doubt the norm for users not to check out everything that they post. Ascertaining the reliability of online sources, even if a user were so inclined, requires more digging than most people have time for, and with Google dominating search engine use, also includes the difficulty of uncovering the political agendas of “cloaked websites” (Daniels, 20098). But beyond the issue of fact-checking is taking a more critical perspective on the sites that we drive traffic to. Morrissey’s articles and the WPMR tumblr were understandably enticing sites for progressives to link to, yet Morrissey’s approach sits uneasily with progressive philosophies around wrongdoing by minors, while WPMR illustrates that the animus that some progressives have towards conservatives goes both up and down the class ladder.

Social media certainly has the capacity for advancing progressive agendas: as a key element of connecting people in mobilizations such as Occupy Wall Street or the various instantiations of the Arab Spring, enabling crowdfunding for projects that would otherwise not be possible, as well as drawing attention to injustice and the efforts against it. In writing this piece, I also traced the Facebook timelines of several people back to July 2009, and found a link to a Salon.com article that eschewed the position of righteous indignation on Gates’ behalf, instead offering a nuanced analysis discussing the complex intersections of race and class involved.9 I’d missed this particular link the first time around amidst the other Gates posts, but it was heartening to see that it had been there.

Finally, I am not innocent in all of this; I have “liked” links without even reading them, not to mention that my newsfeed looks a certain way because of who I am Facebook friends with. My primary goal, therefore, is not to chastise those who linked to the sites I discussed here or even to take those specific sites to task, but to open a discussion about how posts on social media sites meant to signal support of liberal politics can end up reinscribing anti-progressive impulses in a manner more insidious than the phenomena those sites are critiquing. Social media is not charged with the mandate of always promoting constructive debate, but let us still recognize that the effects of mass linking to politically fraught sites don’t simply disappear when those parts of our newsfeeds move down into seeming Facebook oblivion.

Image Credits:

1. One tweet featured in Morrissey’s article after the U.S. presidential elections with the user’s face, name, and username blacked out by me.

2. One of the milder tweets.

3. From the White People Mourning Romney tumblr site.

4. Facebook generic profile picture.

Please feel free to comment.

- Morrissey, Tracie Egan. (2012, November 7). Twitter racists react to ‘that nigger’ getting reelected. Jezebel. Retrieved November 17, 2012, from http://jezebel.com/5958490/twitter-racists-react-to-that-nigger-getting-reelected/gallery/1 [↩]

- Hill, Kashmir. (2012, November 9). Should teenagers have racist election tweets in their Google results for life? Jezebel votes yes. Forbes. Retrieved November 17, 2012, from http://www.forbes.com/sites/kashmirhill/2012/11/09/should-teenagers-have-racist-election-tweets-in-their-google-results-for-life-jezebel-votes-yes/ [↩]

- Morrissey, Tracie Egan. (2012, November 9). Racist teens forced to answer for tweets about the ‘nigger’ president. Jezebel. Retrieved November 17, 2012, from http://jezebel.com/5958993/racist-teens-forced-to-answer-for-tweets-about-the-nigger-president [↩]

- http://whitepeoplemourningromney.tumblr.com [↩]

- http://www.peopleofwalmart.com/ [↩]

- Douthat, Ross. (2012, November 17). The liberal gloat. New York Times. Retrieved November 17, 2012, from http://www.nytimes.com/2012/11/18/opinion/sunday/douthat-The-Liberal-Gloat.html [↩]

- boyd, danah. (2007). Why youth (heart) social network sites: The role of networked publics in teenage social life. In David Buckingham (Ed.), Youth, identity, and digital media (MacArthur Foundation Series on Digital Learning). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; Enli, Gunn Sara and Thumim, Nancy. (2012). Socializing and self-representation online: Exploring Facebook. Observatorio, 6(1), 87-105; Livingstone, Sonia. (2008). Taking risky opportunities in youthful content creation: Teenagers’ use of social networking sites for intimacy, privacy and self-expression. New Media & Society, 10(3), 393-411. [↩]

- Daniels, Jessie. (2009). Cloaked websites: propaganda, cyber-racism and epistemology in the digital era. New Media & Society, 11(5), 659-683. [↩]

- A Phantom Negro. (2009, Jul 24). Skip Gates, please sit down. Salon.com. Retrieved November 17, 2012, from http://www.salon.com/2009/07/24/gates_12/ [↩]

It’s very simple to find out any matter on net as compared to textbooks, as I found this post at this web site.

Helpful information. Lucky me I discovered your site unintentionally, and I’m shocked why this twist of fate did not happened in advance! I bookmarked it.