Aspect Jumping

J.D. Connor / Yale University

Two examples:

1. You are watching The Dark Knight (Nolan, Warners, 2008) at your semi-local IMAX theater, and you have seen, in the first 90 minutes, several sequences where the conventional widescreen jumps out (or, up and down) to fill the enormous near-square in front of you. These are sequences where something undeniably grand is on display—Hong Kong, say—so when it happens this time, as Harvey Dent is being transported in an armored police convoy, you may wonder why. You’ve already seen Chicago-Gotham, and this sequence is taking place in the Blues-Brothers-y world of Lower Wacker Drive. It’s decidedly squat.

But then Batman shows up and hooks the Joker’s semi-truck, flipping it ass-over-teakettle, and as the trailer rises through the image, spanning it top to bottom, and some sternum-shaking, diesel-metal groan crawls up through the stadium seating, you say, “ohhhhh” and now it makes sense that we were in IMAX.

2. You are watching your Local Football Franchise in glorious HD. The new angles that the 16:9 screen makes possible—an all-22 view of the field, or that swooping cable cam on the kickoffs—are thrilling. A pass is completed, or not, right on the sideline, and although you have pretty definitive evidence as a result of some stunning superslomo, they cut to commercial while the ref takes a second look. It’s a locally programmed break, and the first spot is for a car dealer. The image is not only pillarboxed down to 4:3 but within that 4:3 the manufacturer-provided b-roll is letterboxed further down to 16:9. As a result, someone is yelling at you about excellent financing deals while your gorgeous flatscreen shows a miniature, windowboxed image.

The sort of deeply meant aspect jumping we see in TDK is almost absent on television, where shifts from 4:3 to 16:9 and back happen far more often. At some level that isn’t surprising. Hollywood cinema has managed to fret publicly over medium specificity as part of its assertion of cultural primacy even in an era where an ascendant television has made stronger and stronger claims to quality, even superiority. There is a reason that Keanu Reeves can get excited enough about the digital turn that he wants to talk to everyone about it, as he does in the documentary Side by Side (Kenneally, Tribeca, 2012).

But if aspect jumping in film is an occasion for obsession, it has been all but neglected in television studies, and that, too, seems almost natural. Ask yourself: what was the last 4:3 tv show you watched? You probably know that The Master is in limited 70mm release and that it is likely one of the very last films in that format. You probably cannot say what the last 4:3 television series on ABC was. (It was Extreme Makeover: Home Edition.)

Some blame for this ignorance falls to us as scholars. But surely the larger share belongs to television industry itself, which has a vested interest in downplaying epochal events in its own technological history because its industrial organization makes a hash of any such historical breakpoints.

If the digital cinema rollout has been fraught (and I’m underplaying it here), the parallel change in television has been a mess. Each phase—production, distribution, and exhibition—has contributed to a less-than-optimal process and the results have been a blurry historical transition.

For over-the-air consumers, there was a multibillion-dollar digital antenna coupon program that would allow the installed base of SD TVs to continue to work. For cable and satellite consumers, set-top boxes were supposed to adjust the screen image to fit the aspect ratio of the program, but they have tended to be terrible at it. And rather than fish around for the right remote, consumers routinely fail to adjust the display to account for these changes. As a result, millions of televisions are warping the images that they are supposed to show. Not ours, of course, but maybe Mom & Dad’s, certainly Grandma’s, and probably the one in the department seminar room. This can be maddening. Charlie Brooker put it this way: “There are only two kinds of people in this world: those who don’t have any problem with watching things that are randomly stretched or squashed, and decent human beings who still have standards.”

For producers, the HD switchover brought endless handwringing about resolution—would Bill O’Reilly be intolerably blotchy? (Yes.) Would newsdesks look like the cheap constructions they were? (Yes.) How would soap operas survive? (Most didn’t.) —and some angst about “filling the frame.”

Parts of the production side, like sports, adapted quickly. Other multicamera shows had difficulty. You can still see this on talkshows—the standard two-shot is awkward once there is 50% more screen. The Daily Show and others adapted by adding vertical framing monitors in the background, effectively masking down the interview image. But it is still not uncommon to see, say, Jon Stewart’s hands drift into the bottom edge of a one-shot of a correspondent on the right side of the desk.

With a widescreen image, the cameras need to be father apart to maintain clean setups, and many studios make that difficult.

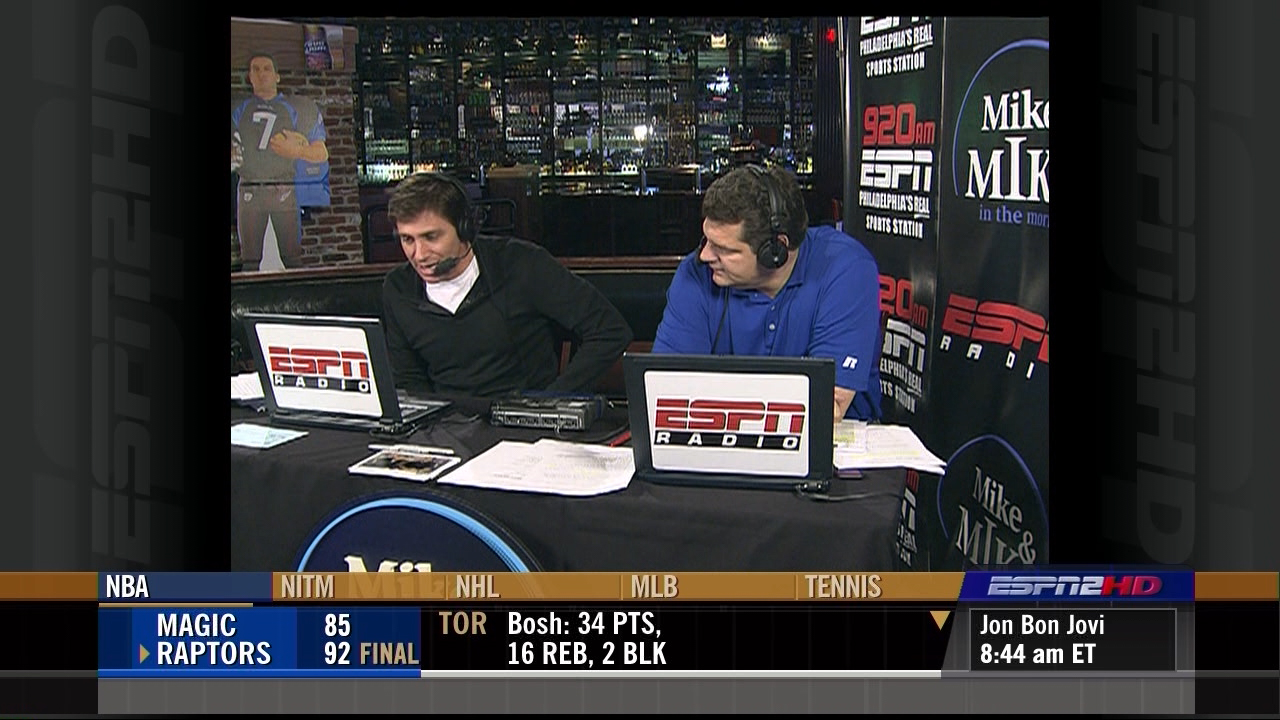

Widescreen posed new and interesting challenges for sports and talk, but it caused all sorts of problems for what I’ll call multisourced programs. Programs that rely on footage provided by others—like news and documentary—find themselves with dead pillars once they go widescreen. Sesame Street shifted to HD in 2008, but its enormous library of animation and short films is 4:3, and so the show jumps all the time. From 2004 to 2007, when ESPN was showing 4:3 footage, they simply threw the ESPNHD logo into the pillars, deadening the space.

In 2007, they opted to squeeze in a version of their “rundown” column on one side, which was a temporary solution.

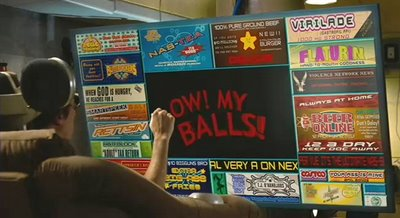

(Down that road lies the madness of the BloombergTV J-frame and the Idiocracy tile-o-vision).

For producers, HD and widescreen conversion was a mark of network confidence. All My Children and One Life to Live were both supposed to switch in 2009. AMC did; OLTL did not, and that was a clear indication that it was doomed. Last Call with Carson Daly converted in 2011, becoming the last series on NBC to make the move, making it clear how little the network had invested in the show.

But no matter how confident a network might have been, no matter how large the investment in new sets and new cameras might be, television producers are unable to insist upon the meaningfulness of aspect ratio changes because even today distribution and exhibition can undo them. Lost might have been shot in widescreen from the get-go, but your local cable company might have sent it out as a standard signal, perhaps letterboxed, perhaps clipped. Who knows?

Contrast all that with a second cinematic example, Argo, (Affleck, Warners, 2012), a love letter to the film industry and all its various arts and sciences. The early scenes of Iranian students overrunning the U.S. embassy in Tehran jump back and forth between widescreen and not-so-widescreen (imdb lists 7 different “source formats,” including some blown-up Super8), and here the rhetorical difference does not read as formal, as in TDK, but as authentic. At the end of the film, the credits roll beneath pairs of images—one from the narrative matched against one from the historical record, a TV still or a news photo. But while the content of the images is still, the images themselves are shifting. As their aspect ratios converge, it becomes easier to compare them. And it becomes easier to assert that the film is accurate, that its production design is excellent, and that cinema maintains its primacy over other media. Argo’s nostalgia registers its bad faith.

Image Credits:

1. The streets in The Dark Knight – screen capture by author

2. Jon Stewart’s hands enter the frame on The Daily Show – screen capture by author

3. ESPN’s logo in pillars

4. ESPN adds another column – screen capture by author

5. BloombergTV’s J-frame – screen capture by author

6. Idiocracy‘s busy tile-o-vision – screen capture by author

Please feel free to comment.

Pingback: Space Ghosts: Cartoons and Talk Shows J.D. Connor / Yale University | Flow