When Screens Touch Back

David Parisi / College of Charleston

Jacques Derrida1

“When you’re thinking about computers, touch is dramatically missing. And it’s so profound. It’s the first sense in your life, and it’s probably the last one. From a tactile standpoint, a touchscreen is literally dead.”

Christophe Ramstein, Chief Technology Officer, Immersion Corporation

2

The current proliferation of mobile computing technologies would be unthinkable without the touchscreen interface. Tablets, smartphones, e-readers, dashboard automobile entertainment systems—all depend on the finger’s ability to dexterously manipulate onscreen representations. But the imperative to manipulate the images using our digits brings with it a corresponding desire to reach through the screen and feel the thing being represented. The act of holding the screen, the process of manipulating, caressing, rubbing and pinching the image it presents leaves the fingers hungry for lost tactile sensations. This memory of sensations lost, a memory that haunts the fingertips, signifies what C. Nadia Seremetakis describes as “the numbing and erasure of sensory realities.”3 Sensorial experience, when subjected to the pressures of changing perceptual technologies, fragments and breaks down, before being coated in dust and eventually forgotten.

Rather than merely serving to index lost sensations, I want to understand the touchscreen’s flat glass, and the benumbed finger that comes into contact with it, as a potentially generative space. The touchscreen, approached from this perspective, becomes capable of marking “moments of socio-cultural transformation”4 by exploding possibilities of distanced contact and virtualized touch. While it might be tempting to indulge this nostalgic lament over lost tactile sensations, an interface designer like Ramstein seizes the finger as a dormant channel that might, under the right conditions, be flooded with new information.

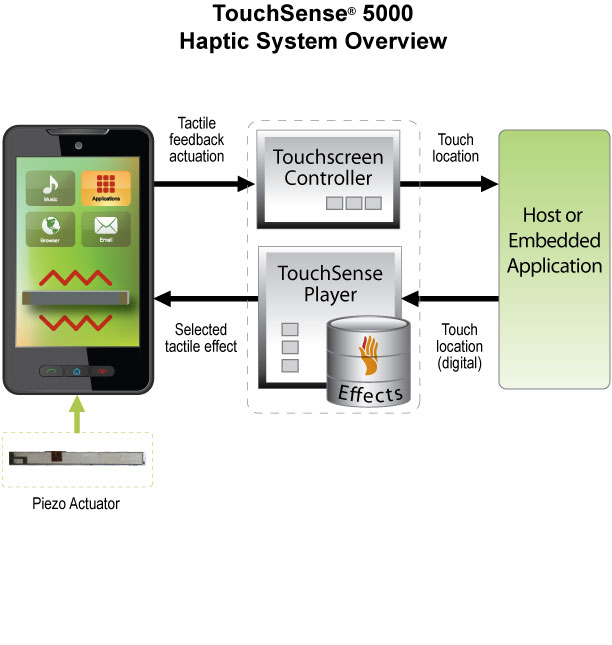

The contact between user and screen, devoid of tactile differentiation, becomes for the interface designer a canvas onto which he can paint a range of new sensations. Using an array of techniques—for example, mechanical vibrations transmitted to specific points of contact on the screen, or electrostatics to produce sensations in the fingertip—screens acquire a layer of tactile sensations. Banks of ‘tactile effects’—discrete sequences of code that control the interface at a material level—coordinate the sensation felt by the finger as it moves across the glass. By providing a stable storehouse of repeatable and standardized cues for touch, these tactile effects enter into a semantic relationship with visual and auditory sensations.

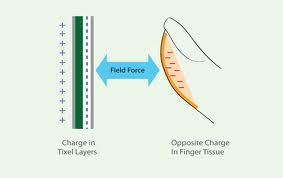

By submitting to further technicization, a benumbed perceptual modality reacquires its sensory reality, if only in traces. The visual illusion of texture, rendered through the algorithmic manipulation of pixels, is confirmed and supplanted by a corresponding and temporary illusion of tactile texture, rendered through the algorithmic manipulation of Tixels™. Through electromechanical inscription, the smooth space traversed by the fingertip acquires striations.

So: how do we ‘read’ the tactility of the touchscreen? The interface designer offers one answer: as a space that will inevitably be populated by instrumentalized, machine-generated haptic sensations, capable of restoring the feeling audiovisual interfacing robbed us of. As Baratunde Thurston explained in a segment on haptics for Popular Science’s Future of Communication series:

“our computer user experience has been dominated by sight and sound, but what about touch? […] What if you could experience the texture of an orange, the wetness of water, the presence of a nearby friend? In the future, haptic technology will allow us to connect more naturally to our apps and devices, and give us a closer, more emotional connection to each other.” 5

This vision of touch’s future contains some seductive promises: once our screens become tactile, they will help to ameliorate touch’s alienation from contemporary interface schematics, allowing the fingers to join the eyes and ears in transcending the body’s spatiotemporal limits. And doing so will not induce further feelings of technological detachment, but instead yield a closer and more natural relationship to the technologies that increasingly encroach upon our tactile field.

As students of media, however, we are (rightly) trained to be suspicious of technofetishistic and deterministic narratives. Instead of grounding our analysis in what tactile touch screens promise to do later, we should rather try to understand them for what they are being asked to do, to understand the desires embodied in the various attempts to give touchscreens a dynamic tactility. The following questions then come into view: what economic imperatives are steering and configuring this project of making tactile? What sensations does the screen allow into the tactile field, and which ones does it shield the user from? What sensations are desirable, and which are to be marginalized? What sorts of new intersubjective contacts are opened up? When the screen can touch us, whose touch is it acting as a surrogate for? (Or, “who penetrates whom”6 through tactile prosthesis?)

Tactile touchscreens also signal a renewed fascination with tactile knowledge—an attentiveness to the sensory environment audiovisual media threaten to liquidate. Tactile touchscreens serve as an ‘anti-environment’: by attempting to reconstruct lost tactile sensations, they call attention to the existence of an de-naturalized environment, now understood as constructed. Further, reconstructing these sensations through the haptic interface requires intensifying the nineteenth century project of transforming the various tactile processes into objects of technoscientific knowledge; or as Immersion Corporation nakedly declares: “Haptics is Quite Literally The Science of Touch.”7

Derrida identified—and pushed back against—the spontaneous “tendency to believe that touching resists virtualization.”8 In heeding his advice, we ought to discard our naive assumptions about touch’s fundamental irreducibility to technics, while preparing to confront the consequences of “the archiving of data that are increasingly differentiated and overdetermined in their coding.”9

In my next post, I’ll discuss one of the psychophysiological symptoms of our bonding to mobile screenic devices—phantom vibration syndrome, or vibranxiety– a perceptual ‘disorder’ likely familiar to anyone who has ever owned a mobile communication device with a vibrating alert , from a pager to an iPhone.

Image Credits:

1. Senseg Interfaces

2. Immersion Corporation: TouchSense® 5000

3. Senseg Tixel

Please feel free to comment.

- Jacques Derrida, On Touching—Jean Luc Nancy (Sanford: Stanford University Press, 2005), 300. [↩]

- “Pop Sci’s Future of Communication: Haptics,” Popular Science, accessed October 17, 2012, http://science.discovery.com/tv-shows/pop-scis-future-of/videos/popscis-future-of-haptics.htm [↩]

- C. Nadia Seremetakis, “The Memory of the Senses: Historical Perception, Commensal Exchange, and Modernity,” Visual Anthropology Review 9, No. 2 (Fall 1993): 2. [↩]

- Ibid. [↩]

- “Pop Sci’s Future of Communication: Haptics.” [↩]

- Michel Foucault, The History of Sexuality Volume 3: The Care of the Self (New York: Pantheon, 1986), 30. [↩]

- “What Is Haptics?,” Immersion Corporation, accessed October 17, 2012, http://www.immersion.com/haptics-technology/what-is-haptics/index.html [↩]

- Derrida, On Touching, 300. Emphasis original. [↩]

- Ibid., 301. [↩]

Pingback: When Screens Touch Back | Comm / Tech / Theory / Society