Free to Be You and Me

Kristen Hatch/UC Irvine

Free to Be You and Me turns forty this year. Like thousands of other children, I owned both the record album and the book, and at some point I watched the television special, which aired for the first time in 1974; to this day, I can recite much of the “Boy Meets Girl” skit by heart. Free to Be was the brain child of actress Marlo Thomas and Ms. Magazine editor Letty Cottin Pogrebin, who had introduced the “Stories for Free Children” feature in the magazine. Like those stories, Free to Be You and Me invited parents to engage their children in the great twentieth-century experiment in gender-neutral child rearing, an idea that was particularly appealing to middle-class women like my mother, whose ambitions had been stunted by the demands of domesticity and by social conventions and legal policies that limited women’s access to jobs.

Ms. promoted the album with an exhortation to “liberate little ears,” noting that “the sounds of sexism are all around us—and children are the first to hear them.” The project reflects a faith in the power of media to shape ideology, carefully crafting its messages to counteract the representations of women found throughout popular culture” The poem “Housework,” read by Carol Channing on the album, offers a rudimentary introduction to media literacy:

You know, there are times when we happen to be

Just sitting there quietly watching TV,

When the program we’re watching will stop for a while

And suddenly someone appears with a smile

And starts to show us how terribly urgent

It is to buy some brand of detergent . . .

“That lady,” the poem explains, “is smiling because she’s an actress. And she’s earning money for learning those speeches.” Rather than imagining that housework is a fun sport for women, listeners are exhorted to share the burden of cleaning.

Promoted in the pages of Ms. Magazine as “the very first record that is designed for use by children of all ages, colors, and sex [sic],” Free to Be offers the vision of a future that is not shaped by stale gender and racial ideologies. The opening song, “Free to Be . . . You and Me” describes an imagined world, perhaps a future forged by the album’s young listeners, in which “every boy . . . grows to be his own man” and “every girl grows to be her own woman.” The song is followed by a brief skit, “Boy Meets Girl,” in which two babies (voiced by Mel Brooks and Marlo Thomas) try to determine their gender:

Hi.

Hi.

I’m a baby.

What do you think I am, a loaf of bread?

The babies rely on faulty visual cues (his dainty feet, her bald head) and gender stereotypes (she wants to be a fireman, he aspires to become a cocktail waitress) to identify their genders until a diaper check reveals the “truth” (“You’re a boy, and I’m a girl!). The skit conveys Free to Be’s central message, that biology is not destiny. This message is reinforced by “Parents are People,” in which Thomas and Harry Belafonte sing “Parents can be almost anything they want to be,” and “When We Grow Up,” performed by Michael Jackson and Roberta Flack for the television show, where an overturned fishbowl serves as an astronaut’s helmet in their imagined future explorations of the moon.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EwJaDK02CAk[/youtube]

This message of self-determination is reinforced in the retelling of a Greek legend, “Atalanta” voiced by Thomas and Alan Alda, in which a king offers his daughter’s hand in marriage to the swiftest runner in the land. Atalanta agrees to the arrangement, provided she be allowed to participate in the race, and if she wins she can choose whether she wants to marry at all. Every night she practices her sprints until she has run the course faster than anyone before. However, a local boy, Young John, also practices regularly, and on the day of the race the two are tied at the finish line. The story ends ambiguously; one day they might marry, but then again they might not. Meanwhile each will explore the world. Through their hard work, they have earned the right to determine their futures.

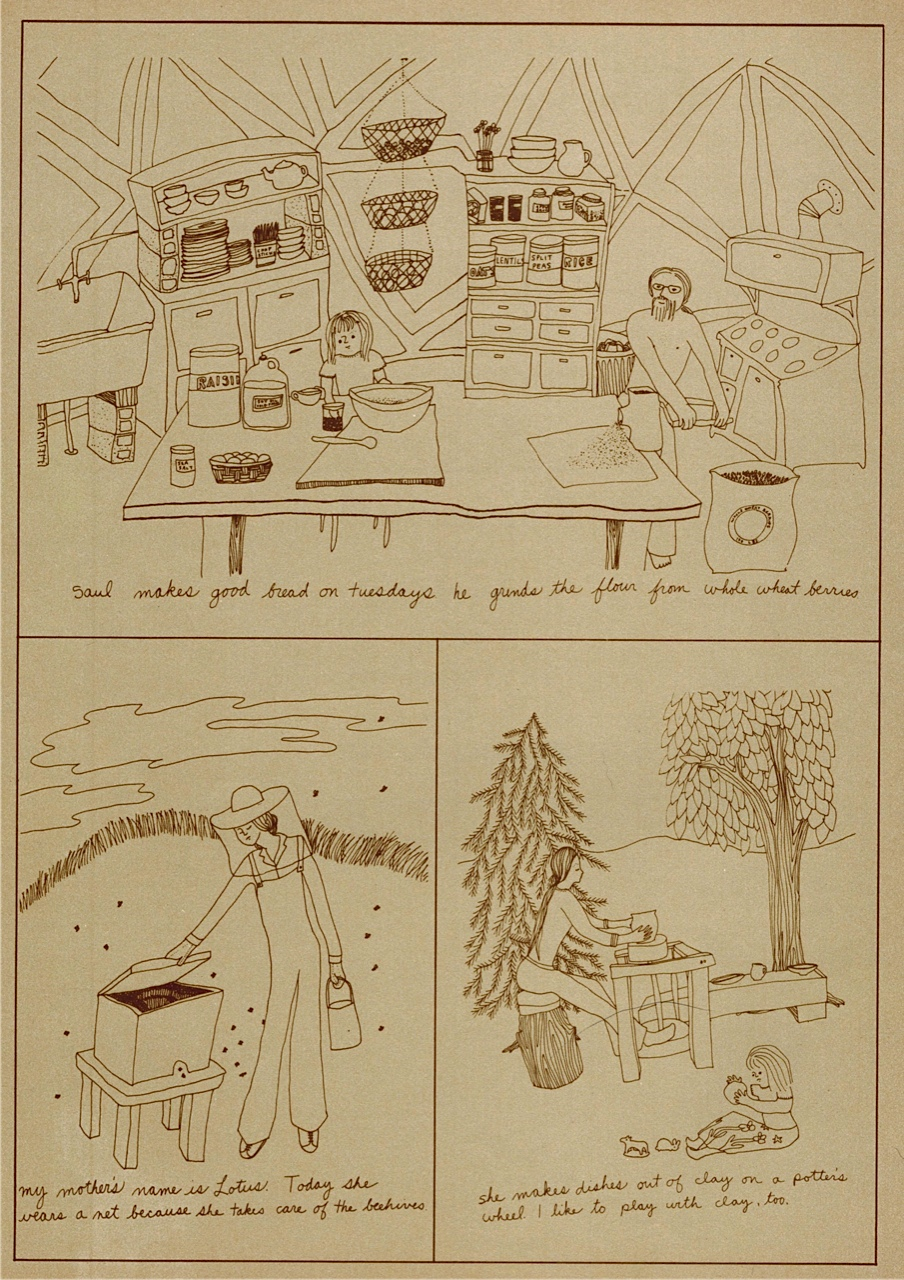

At the time of its release, Free to Be met with its share of criticism. “Housework” inspired complaints from women who objected to its representation of domestic labor as universally loathsome. Indeed, in suggesting that it is more demeaning to smile over housework than it is to smile because one is paid to smile, the story implies that the problem with housework is not that it is gendered but that it is unremunerated. Likewise, radical feminists criticized the album’s valorization heterosexuality and the nuclear family. Not included in the book, album, or television show were stories like “Sylvie Sunflower” by Alicia Bay Laurel, which depicted daily life on a commune. Rather, consumerism and traditional parenting are celebrated in songs like “William’s Doll,” which doesn’t so much embrace variety in children’s gendered desires as it works to expand the concept of boyhood masculinity to include nurturing (and crying, in “It’s All Right to Cry,” sung by pro football player Rosey Grier). In the song, voiced by Alan Alda and Marlo Thomas, Bill withstands the taunts of the other children and proves himself at every sport, but is denied a doll until his grandmother intervenes, explaining:

William wants a doll

So when he has a baby some day

He’ll know how to . . .

. . . care for his baby

As every good father should learn to do.

At no point does the song suggest that William might make his own doll out of rags, or that he make a trade with the tomboy next door. Rather, the song equates gender with the purchase of various commodities: toys, marbles, a baseball glove, etc.

The children who grew up singing along to songs like “Brothers and Sisters” came of age in Reagan’s America, at a moment when the broad project of economic parity gave way to the goal of prosperity that has dominated American life and politics since the 1980s, when the goal of “equality”—of equal pay, equal access, and equal rights—gave way to the ideal of “freedom,” particularly free markets. Looking back, it’s disheartening to realize that the vision of self-determination that was so central to Free to Be’s songs and skits is also one of the central tenets of neoliberalism, and that the messages so carefully crafted to help children defy the limitations produced in the context of one national discourse would help to obscure the limitations produced by another; if anything, it has become more difficult to envision an identity outside the marketplace than it was in 1972. If we’ve learned anything over the last forty years, it’s that the media work in unpredictable ways.

Image Credits:

1. Ms. Magazine, Free to Be You and Me, Album Art, November 1972, from author’s collection

2. Ms. Magazine promotes Free to Be You and Me, from author’s collection

3. Ms. Magazine, November, 1972, from author’s collection

4. Illustration from Sylvie Sunflower, from author’s collection

5. Illustration from Sylvie Sunflower, from author’s collection

Please feel free to comment.

Excellent. And I love that you can embed Roberta Flack and Michael Jackson – will go looking for Alan Alda singing…

The doll example you end on makes me wish there were room for a longer version of this piece that could discuss why and how playing with a doll is gendered in the media age.

For instance, without looking outside the mainstream market for toys, there are lots of action figures (for instance of fire fighters, since you mention them), and of course there’s a story-telling tradition of the stereotypical male making a life-like representation to project wishes unto…