The chef who played too much: Performing masculinities in The Galloping Gourmet

Irina D. Mihalache / American University of Paris

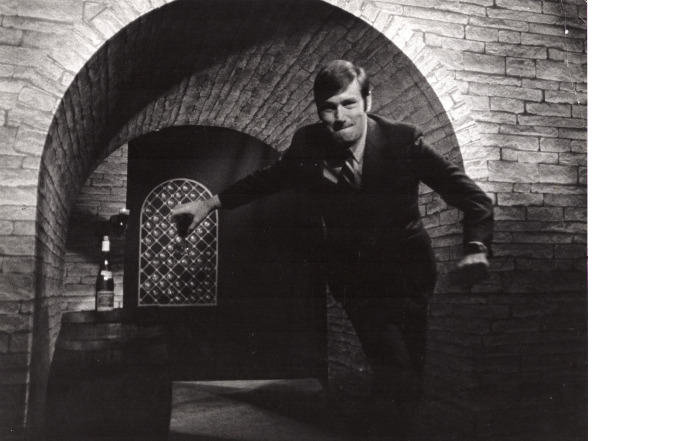

Also known as an “international man of mystery,” Graham Kerr was one of the first performers of masculinity in the kitchen. His very popular show The Galloping Gourmet1, which was broadcasted between 1969 and 19712, sums up many of the stories about masculinity told in cooking shows today. Kerr used the kitchen space as a playground, a laboratory and classroom; he surrounded himself with objects which were associated with high class British masculinity in the seventies; and cooked in a casual and effortless manner. On the Cooking Channel website, Kerr is described as a “trailblazer” chef who “does not take himself seriously” and “delights viewers with culinary shenanigans and mishaps.” What defines Kerr as a chef is his playfulness in the kitchen, his sense of adventure and his ability to entertain while cooking.

In this first article about men in the kitchen, I will explore how the kitchen has been transformed into a legitimate stage for the performance of different discourses about masculinity by analyzing discourses of play. I start my story with Graham Kerr because I find him to be a prime example of playfulness in the kitchen. In The Galloping Gourmet, playfulness is constructed through a mix of entertainment, experimentation and education. The legacy of these narratives of play can be observed today in the kitchens of many Food Network celebrity chefs, from Guy Fieri to Alton Brown.

The kitchen as a masculine space: How cooking became play

Most of the literature which explores the social and cultural significance of the kitchen analyzes the kitchen as a gendered and domestic space.3 The introduction of masculinity into the study of kitchens and cooking happens through a revisiting of discourses around domesticity.4 In a study of the cooking section of Playboy in the 1960s, Joanne Hollows argues that a new type of masculinity was being developed in opposition to the white suburban middle class breadwinner, who was a symbol of domesticated masculinity. The new urban cook of the sixties was performing within a new kitchen space, ridden of all symbols of domesticity, “designed for efficiency with the minimum of fuss and haus-frau labor” (Playboy’s Penthouse Apartment qtd. in Hollows, p. 145).

The process of making cooking “safe” for men included the emphasis on play and experimentation as the main difference between masculine cooking and domestic suburban cooking. While women cooked out of necessity, the new man of the 1960s cooked out of pleasure. This discourse framed the practice of cooking into a game where the man could play with the food out of self-satisfaction. In The Galloping Gourmet, Kerr’s relation with the kitchen and the food is mediated through a playful performance which I deconstructed in the following genres: play as entertainment, play as experimentation, and play as education. While all these types of play act together throughout the shows to compose the performative moments produced by Kerr, I will explain, through examples, how each form of play informs the larger construction of masculinity.

Play as entertainment: How to lard your rump

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=czrj4yJm6z0[/youtube]

If Graham Kerr is first and foremost an entertainer, his playfulness comes across from his use of space as he enters the set running, shaking the hands of audience members and finally jumping over a chair, which has became his signature move. The ownership of the different spaces—the kitchen, the lounge, the dining room, even the audience seating area—within which Kerr moves during the show with grand gestures, signifies his dominant relation with the space. Despite his position of power, his gestures are friendly and playful, as he jumps, strolls, pirouettes, stumbles, (almost) falls, and wanders around. When he cooks, Kerr’s intention is to mock the rules of high gastronomy by improvising and using non-traditional tools, such as an oversized spoon or a larding needle. In the episode “Beer and Rump Pot Roast,” Kerr explains how to lard a rump by introducing a long larding needle filled with lard through the roast. Kerr makes fun of the tool he is about to use, referring to the needle as “a groovy thing”. He adds, “If you’ve got a butcher who knows how to lard a piece of meat, give him…or give me his address.” Obviously, his first attempt fails, as the needle misses the rump. He laughs, the audience laughs and Kerr attempts again, this time with success. The audience claps.

Play as experimentation: How to “orientalize” your crème brûlée

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GfH1_jo4ywI[/youtube]

Kerr’s dishes, when not prepared with unusual tools, are marked by experimentation through the use of “ethnic” ingredients. While today, lychee and Saigon cinnamon are no longer unusual to our diets, in the 1970s, such ingredients were markers of experimentation and bravery in the kitchen. I believe that one other ingredient of Kerr’s masculinity in the kitchen is his sense of adventure when it comes to “spicing up” a classic recipe such as the crème brûlée. In the “Crème Brulee” episode, Kerr prepares a glaze out of lychee which he defines as “an Oriental fruit” and a “heavenly nectar”. He takes time to explain to his audience the anatomy of the lychee fruit and even asks if anyone has ever had a lychee before, to which only one hand in the audience indicates an affirmative answer. As a world traveler, Kerr brings back knowledge which he translates into different forms of experimentation. To experiment in the kitchen is a form of play which also solidifies Kerr’s masculinity.

Play as education: How (not) to measure your ingredients

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qbjr_gIRyKI[/youtube]

Kerr’s kitchen also acts as a site of education where lessons are taught in a casual and humorous manner. The chef, despite his impressive culinary pedigree, often acts contrary to his rigorous training, opting for fun and innovative teaching strategies. One of the most prominent narratives throughout his shows revolves about (not) measuring. More specifically, he offers shortcuts for measuring ingredients to speed up the cooking process and to entertain his audience. For example, in the “Jambalaya” episode, he measures 8 ounces of onion in relation to the palm of his hand, which is supposed to cover entirely the vegetable. Later in the same episode, he gives a lesson in happiness. The best way to get there, he claims, is to “chuck away those measuring cups.” While stepping on some measuring cups, he yells, “I wanted to do that for years.” Giving away the ideal of precision while cooking represents another signifier of masculine power and playful casualness. While everyone understands his joke, there is something powerful and liberating in being able to cook without the constraints of culinary rigors. Kerr makes the point that his cooking is primarily for pleasure and fun and not out of necessity.

In conclusion, I explored The Galloping Gourmet as a significant cultural space where masculinity is constructed and performed through the practice of cooking. Graham Kerr embodies different renditions of masculinity through his playful performances. Entertainment, experimentation and education are all facets of a discourse of play which legitimizes the man’s new locus within the domestic kitchen. I believe that cooking shows, analyzed through their location—the kitchen—and the performance of their chefs can open up significant discussions about the presence of men in the kitchen. I will continue such conversations in my two future articles, which take a glance at two other men who play well in the kitchen—Guy Fieri and Alton Brown.

Works Cited

Hollows, J. (2002). The bachelor dinner: Masculinity, class and cooking in Playboy, 1953-1961. Continuum, 16(2): 143-155.

Image Credits:

1. Cooking Channel Blogs, “Serious Cooks, Seriously Funny”

2. Galloping Gourmet Safari

3. Screen capture by the author from the episode “Filet Van Zeetong Nerleoise” http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VASO8NdEoYM.

Please feel free to comment.

- The Galloping Gourmet was the first cooking show in North America filmed with an in-studio audience. The show’s main goal was not to teach people how to cook but to entertain audiences through cooking, which explains why the Christian Science Monitor called Graham Kerr “a cooking entertainer” (Collins, 107). The format of the show was innovative for the inclusion of filmed footage from Kerr’s culinary trips around the world and for showing Kerr move around from his lounge to his kitchen to his dining room. Kathleen Collins best describes Kerr’s performance: “the show opened with the snappily-dressed, British dandy of a ball of energy leaping over a tall kitchen chair while holding a full glass of wine” (p. 106). In each episode, Kerr cooked one single recipe inspired by one of his travels, which he tasted together with one lucky guest from the audience at the end of the show. [↩]

- The Galloping Gourmet is now re-broadcasted on the Cooking Channel. [↩]

- For works which look at kitchens as sources of women’s oppression, please see Haydon, D. (1994). The grand domestic revolution. Cambridge: MIT Press; Matrix (1984). Making space: Women and the man-made environment. London: Pluto. For more recent, cultural studies approaches to kitchens, please see Floyd, J. (2004). Coming out of the kitchen: Texts, contexts and debates. Cultural Geographies 11, 61-73. [↩]

- For works which look at masculinity in the kitchen please see Swenson, R. (2009). Domestic divo? Televised treatments of masculinity, femininity and food. Critical Studies in Media Communication 26(1): 36-53; Gorman-Murray, A. (2008). Masculinity and the home: A critical review and conceptual framework. Australian Geographer 39(3): 367-379. Feasey, R. (2008). Masculinity and popular television. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. [↩]

Pingback: Being Guy Fieri: The “chef-dude” and the geography of a bro kitchen Irina Mihalache / American University of Paris | Flow

Pingback: The Rise of the Hot Chef, From 'The Bear' to Instagram