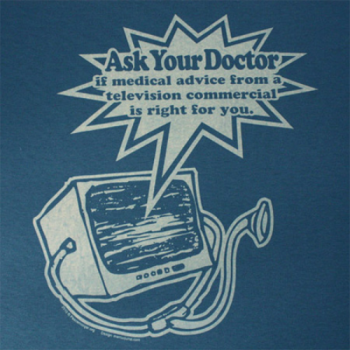

“Ask Your Doctor”

Black Hawk Hancock / DePaul University

Pharmaceutical advertisements have come to dominate our media-saturated environment. Whether on TV, print or internet, someone is constantly urging you to “Ask your Doctor.”

In trying to establish guilt for the contemporary inseparability among health, medicine, and commerce, before demonizing physicians for their God-like-complexes, vilifying Big Pharmaceutical in their blood thirst for profits, chastising advertising for their manipulative campaigns, or castigating politicians for allowing the US to be one of only two countries in the world that are exposed to direct-to-consumer-advertising, you may want to “ask your doctor” what role you play in all of this.

It has long been established that effective advertising works, not because it cajoles us into believing something that is not true, but because it taps into something already out there in the culture that is being reflected back to us. In the Sociology of Health, the scapegoat of doctor-bashing for all medical related problems has become passé, just as the rise of the Pharmaceutical-Industrial-Complex has become a reality shaping all areas of our health care—from research to policy to delivery. Yet, despite the clarity of the elephant in the room, we still wonder, should I “ask my doctor” if I need this or that medication, of if I may have this or that condition. As the first of three articles written for Flow, the purpose of this column is to agitate the conversation around what these advertisements may do in terms of their effect on our behavior, what they may mean in terms of their representativeness of contemporary society, and what they may induce in terms of our dispositions and orientations toward the world around us.

A recent study by the Commonwealth Fund polled 2,100 people aged 19 to 64 and found that 26 percent of non-elderly adults went without insurance—a percentage that equals about 48 million people when measured against U.S. Census data1. In addition, 7 in 10 of those who lost insurance spent a year or more without coverage, partly because plans sold on the individual market for health insurance were unaffordable. Without insurance, people quickly disconnect from the healthcare system by avoiding basic medical services such as routine doctor visits and screenings for cancer, cholesterol and high blood pressure2. In addition, it has been reported that the cost of family coverage has about doubled since 2001, and trends indicate that people will be paying a larger share of their own medical bills through higher deductibles and co-payments. Finally, The Kaiser Family Foundation documented how almost three-quarters of workers now make at least partial payment per medical visit, and nearly 1/3rd of those surveyed had a minimum annual deductible of $1,000 for single coverage, up from just 1 in 10 in 20063. These reports, coupled with denial of coverage for pre-existing conditions, not being able to select their preferred doctor due to insurance regulations, and lack of a consistent primary care physician at clinics are well-documented facts and not myths4.

Whether we suffer from, or more might suffer from one or more of a host of conditions: that our sadness could be the source of depression, or that our worries maybe signs of a deeper general anxiety disorder, that our inability to concentrate could be an undiagnosed Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, that we may have high blood pressure, sexual dysfunction, or possibly be at risk for something much more dire, the only way to be sure, we are told, is if we “ask our doctor”

Three key points of discussion emerge out of these situations:

First, the unending stream of “ask your doctor” ads that flow through our mediascape on a daily basis is too numerous to count, as they become so ubiquitous they blend into the rest of the advertisements that circulate around us. Whether or not we choose to pay attention to them, they form part of the fabric of that information flow.

Second, if we do choose to stop and take notice, medical knowledge and medical authority are so deeply engrained in our culture and psyches that our new self-diagnosing, WEBMD friendly world (amongst dozens of other informative sites), primes us to check and double-check our current health status. Self-evaluate, then “ask your doctor.”

Third, through direct to consumer advertising, the pharmaceutical industry has simultaneously concentrated its authority and empowered its consumers. While providing some, but not all information to the public, they promote awareness without providing full information, e.g. the Federal Drug Administration Modernization Act of 1997, and revision in 2004, requires that “major” side effects only be “listed” (needing to be neither spoken of, nor focused on for federal compliance)5. DTCA has provided patients, (read customers), with a newfound sense of autonomy, self-help, self-reliance, and empowerment, as they are now interpellated—the Althusserian expression for the process by which we recognize ourselves as subjects in the dominant codes and institutions of a society, which simultaneously make us individuals and complicit in our own domination— into this system of medical knowledge6. No longer the passive recipient of medical attention, people are now able to actively relate, identify, and define themselves as active shapers of their health and lifestyle. What was once the province of physicians alone, has now become part of the public domain. While doctors must still write prescriptions, if someone is suffering from, or may be suffering from some medical condition, and a possible treatment is available, if one doesn’t “ask their doctor,” then who else is to blame but yourself?

As the welfare state withers away under the triumph of neoliberalism, it falls upon the individual to take initiative for her health, her responsibility to seek out insurance coverage, her responsibility to be examined and to seek out treatment. While this self-reliant ethic of personal responsibility and self-accountability releases the State from having to care for its population, whether oblivious or curious, empowered or unemployed, it falls upon the individual to take care of herself. Maybe you should “ask your doctor” if this responsibility comes with a price tag too high to pay.

Looking at direct to consumer advertising points the finger of responsibility right back at us. DTCA is a symptom, not a cause of our illness. Big Pharmaceutical, is no different than Big Tabacco or Big Automobile or Big Wal-Mart, each a corporation that seeks to make a profit. Each of these economic powerhouses employs lobbyists and holds the purse strings of election funds for the politicians who run for office, that in turn enact the laws that so weakly regulate them. And last, but not least, let us remember not the leaders of these evil empires, but the employees of these corporations and public offices, and all the people who work with and for them, as well as those who educate their children, repair their homes, and deliver their mail, who elected these official into office, the circle of responsibility grows so large it comes to encompass people who look exactly as you and I. Let us consider those people, a population without universal health care and a social contract that ensures the benevolent care of each and every citizen, when an advertisement suggests to them, “ask your doctor,” hopefully they have one to ask.

Image Credits

1. Marcus Jump

- The Commonwealth Fund [↩]

- The Commonwealth Fund [↩]

- Abelson, Reed. 2011. “Health Insurance Costs Rising Sharply This Year, Study Shows” September 27. New York Times [↩]

- The Kaiser Family Foundation provides one of the most comprehensive publicly available sites on the status of health care [↩]

- Mulligan, Lia. 2009. “You Can’t Say That on Television: Constitutional Analysis of a Direct-to-Consumer Pharmaceutical Advertising Ban.” American Journal of Law and Medicine 37:444-467. [↩]

- Althusser, Louis. 1972. “Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses” in ↩]