Film, Nostalgia, and The Digital Divide

Wheeler Winston Dixon / University of Nebraska-Lincoln

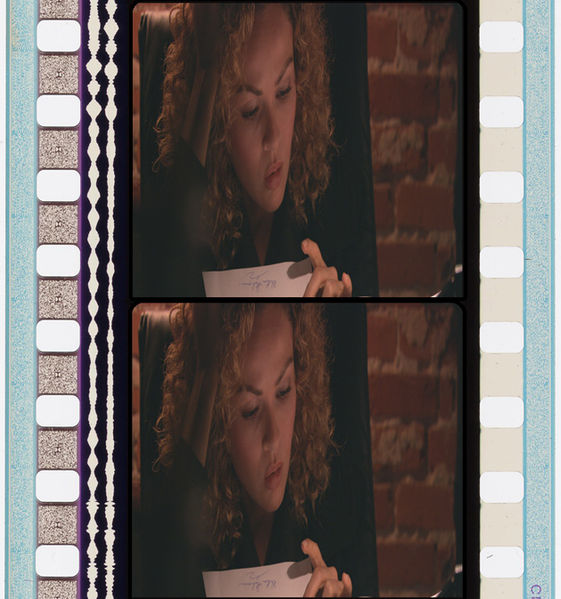

A few days ago, I was watching Kathryn Bigelow’s excellent film The Hurt Locker (2008) – on DVD of course – and I was suddenly struck by the fact that it may be one of the last movies to be actually shot on film; in the case of The Hurt Locker, Super 16mm film, with 4 handheld crews working at once, piling up roughly 200 hours of footage to be eventually edited down into a 130 minute film. With its rough, raw look, its smash zooms and its hectic intercutting, mirroring battlefield news photography from the Vietnam war, The Hurt Locker has a visceral reality, especially in its nighttime sequences, that seems to me to be intrinsically tied to the filmic process. You could have the same images in video, of course, but I somehow don’t think the same level of textures and contrasts would be available to you; you’d get a perfect, pristine, scratch free image, but a certain richness to the images would be missing. Digital technology simply doesn’t have the same spectrum of tonal possibilities, and even though it can mimic millions of different shades of color, the end result is cold, artificial, distant. There’s something unreal about it.

When you’re making a film, so to speak, it would be nice to have a choice as to whether or not to use film, or to go with digital. But it seems that the choice has been made for you. Aesthetic issues aside, film is being swept into the dustbin of history. As Richard Verrier reported in the Los Angeles Times, Birns and Sawyer, the oldest film equipment rental house in Hollywood, has thrown in the towel on film — everything’s gone digital. Responding in the shift to all-digital production, the company auctioned off all its film camera equipment, both 35mm and 16mm, though 16mm has been a dinosaur for some time. But now 35mm film is going out the door, too. It’s just like The Jazz Singer in 1927, when films converted to sound; digital is now the only way to go. And it’s happening fast.1

As Verrier2 wrote,

”call it film’s last gasp. Birns & Sawyer, the oldest movie camera rental shop in Hollywood, made history last week when it auctioned off its entire remaining inventory of 16- and 35-mm film cameras. Owner and cinematographer Bill Meurer said he didn’t want to part with the cameras, but had little choice as the entertainment industry has largely gone digital. ‘People aren’t renting out film cameras in sufficient numbers to justify retaining them,’ Meurer said in an interview at his North Hollywood warehouse, where he rents out cameras, lenses, lighting equipment and grip trucks. ‘Initially, I felt nostalgic, but 95% of our business is digital. We’re responding to the market.’

The auction underscores just how rapidly Hollywood is transitioning to digital. Theater chains are increasingly converting their multiplexes to digital projectors because studios are soon expected to stop releasing film prints altogether. And major camera manufacturers such as Arri and Panavision have for now halted production of new film cameras (although they are still doing upgrades on film equipment). Today, virtually all television production and about one-third of all feature films are being shot digitally.”

As far back as 2000, in a lecture in Stockholm, Sweden, I predicted this shift would happen, not with much enthusiasm, but simply as a matter of fact. At the time, there was one digital theater in New York, and the executives made a big show of dumping 35mm film canisters into a trash bin as a demonstration of their embrace of digital technology. It made for an apt, if distressing image; film was heading for the dump. An audience member replied that what happened in one small theater in New York couldn’t possibly threaten the hegemony of film production and exhibition; it was simply too ubiquitous, and too ingrained. There were literally millions of 35mm features. And 35mm was about to become obsolete? Ridiculous. I remember, too, appearing on a talk show on NPR with director Bennett Miller around the same time; I predicted digital would replace film within five years, and everyone in the room thought I was crazy. It’s taken a bit longer than that, but now the day of all-digital production is here.

And with this shift, of course, comes digital projection, and a whole new level of studio control. Once upon a time, when you screened a film at a theater, you took the 35mm print out of the shipping case, threaded it up, checked the aspect ratio, focus, and sound level, and ran the film. If you wanted to do an additional screening for a critic, or add an extra show, you could. If you wanted to switch the movie from one screen to another in your theater, you could. If short, you had the time, and the freedom, to have some measure of control over the projection of the films you screened.

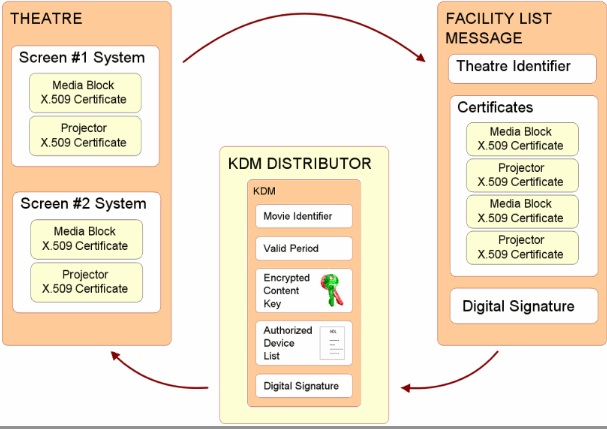

Not anymore. With digital projection comes a series of encryption codes, called KDMs, which must be used to “unlock” the digital files for projection, often within windows as short as four hours. Switching screens or adding additional shows now has to be cleared with the distributor every time, usually by e-mail. You can’t just pull the film and run it anymore. It has to be approved, and unlocked with a KDM, on a case-by-case basis.3

As this excerpt from “Digital Cinema Technology: Frequently Asked Questions”4 notes,

“KDM is the acronym for Key Delivery Message. The security key for each movie is delivered in a unique KDM, one KDM per digital cinema server. The security key is encrypted within the KDM, which means that the delivery of a KDM to the wrong server or wrong location will not work, and thus such errors cannot compromise the security of the movie. The KDM is a small file, and is typically emailed to the exhibitor. To create the correct KDM, however, requires knowledge of the digital certificate in the projection system´s media block.

KDMs have only a few [emphasis added] conditions associated with their use:

A KDM will only work for one movie title on one server.

A KDM will only work within the prescribed engagement time period.

To play a movie on two servers requires two KDMs for the movie. This means that to move a movie to a 2nd server requires a 2nd KDM. The engagement time window of the KDM is set per the business requirements of the studio distributing the movie. If your KDM expires and you don’t have a new KDM to continue on the engagement, then you cannot play the movie.”

This is about studio control; nothing more. It takes any authority away from the exhibitor; it’s a hypersurveillance system that comes from the top down, and limits what theater owners can do. Digital projection may have many significant attributes — superior picture and sound, no scratches, clean, crisp images — but now movies don’t really exist unless they’re unlocked by the KDM, and have no portability. This is what the studios want. It’s good for the public, or critics, or exhibitors — a real measure of discretionary freedom has been lost.

But at the same time, those 35mm facilities that still exist are facing obsolescence on two fronts: there are fewer and fewer 35mm prints being made available, and at the same time, since very little 35mm film is being manufactured and/or used, it’s becoming increasingly hard to find parts for 35mm projectors, cameras, or anything else associated with the film medium. Several years ago, I was lucky enough to obtain a 35mm print of Alain Robbe-Grillet’s superb, hypnotic first feature, L’Immortelle (1963), directly from the French Cultural Service, and to screen it for my students in class. They were completely enthralled by it, and by the experience of seeing the film in its original 35mm format, with all the tonal depth – even though the film is in black and white – that film can afford.

But even as we ran it, I reminded them that the film would then have to be crated up and sent back to Paris, and that this was a one-time-only experience; the film is unavailable on DVD, Blu-ray, or even VHS, much less 16mm; it’s only available in 35mm. To convert to a digital master and then release it would cost too much money, even with a down-and-dirty transfer, to make its investment back, apparently; the film will remain in limbo, inaccessible to all but the most dedicated historians. And now, the equipment we used to project the film is threatened, as well. Parts are hard to come by. The equipment is breaking down. Service technicians are harder to locate. Everyone is headed full force into the future, and has no time for the past.

Many, many years ago, when I was teaching at Rutgers University, we used to run screenings of films in Scott Hall 123 nearly every night of the week. We screened 16mm prints, the screenings were open to all, and the equipment we used was simple in the extreme; a Bell and Howell Model 535 projector, with a 1200-watt incandescent lamp that cost about $15 to replace, and some speakers plugged into the projector, and placed on the stage in front of the screen. We ran all-nighters quite often, and we regularly had additional screenings as audience demand dictated. We screened the films again and again, memorizing them, seeing them, albeit in reduced form, in the medium in which they were made.

Now, of course, you can stream a lot of films, and the number of titles available increases daily. You can screen them on your laptop, your iPad, even on your 50’ plasma, but you won’t get the experience of seeing these images on film, with all their attendant qualities and defects, and you won’t get the communal experience of seeing them with an audience. Movie viewing in the 21st century has become, more and more, a solitary vice, in which one person tunes out the rest of the world, and tunes into a digitally perfect copy of a film, without having to participate in a group experience.

I’ve said this before, but it bears repeating; it isn’t the same experience. And while it’s fine that digital copies of the masterpieces, and the junk for that matter, of the past, are available for viewing, it would be nice to have a choice in the matter. That’s something that’s been taken away from us – and apparently, we didn’t even notice.

Image Credits:

1. Film and Digital

2. 35mm Camera

3. KDM Diagram

4. 35mm Film

5. Bell and Howell Model 535 Projector

Please feel free to comment.

- Dixon, Wheeler Winston. “Hollywood’s Oldest Production Rental House Sells All Film Cameras,” Frame by Frame October 26, 2011. Web. [↩]

- Verrier, Richard. “On Location: Birns & Sawyer Auctions Its Film Cameras,” the Los Angeles Times, October 25, 2011. Web. [↩]

- Dixon, Wheeler Winston. “Digital Projection, KDMs, and Studio Control,” Frame by Frame November 17, 2011. Web. [↩]

- “Digital Cinema Technology Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs),” MKPE Consulting January 2012. Web. [↩]

Since I wrote this essay, Christopher Nolan has come out forcibly in favor film, for as he notes, digital will take care of itself, but it would be nice to have a choice. As Nolan pointed out in a recent DGA interview with Jeffrey Ressner,

“For the last 10 years, I’ve felt increasing pressure to stop shooting film and start shooting video, but I’ve never understood why. It’s cheaper to work on film, it’s far better looking, it’s the technology that’s been known and understood for a hundred years, and it’s extremely reliable. I think, truthfully, it boils down to the economic interest of manufacturers and [a production] industry that makes more money through change rather than through maintaining the status quo. We save a lot of money shooting on film and projecting film and not doing digital intermediates. In fact, I’ve never done a digital intermediate. Photochemically, you can time film with a good timer in three or four passes, which takes about 12 to 14 hours as opposed to seven or eight weeks in a DI suite. That’s the way everyone was doing it 10 years ago, and I’ve just carried on making films in the way that works best and waiting until there’s a good reason to change. But I haven’t seen that reason yet.

I’ve kept my mouth shut about this for a long time and it’s fine that everyone has a choice, but for me the choice is in real danger of disappearing. So right before Christmas [2011] I brought some filmmakers together [which included Edgar Wright, Joe Dante, Michael Bay, and Bryan Singer to name a few] and showed them the prologue for The Dark Knight Rises that we shot on IMAX film, then cut from the original negative and printed. I wanted to give them a chance to see the potential, because I think IMAX is the best film format that was ever invented. It’s the gold standard and what any other technology has to match up to, but none have, in my opinion. The message I wanted to put out there was that no one is taking anyone’s digital cameras away. But if we want film to continue as an option, and someone is working on a big studio movie with the resources and the power to insist [on] film, they should say so. I felt as if I didn’t say anything, and then we started to lose that option, it would be a shame. When I look at a digitally acquired and projected image, it looks inferior against an original negative anamorphic print or an IMAX one.”

You can read the entire interview at the website below; all I can say is that here’s someone who has completely embraced CGI and the effects it can produce, but who is still convinced that film has a unique quality that nothing can really duplicate. If the possibility of using film is lost, it will be a significant blow to the art of the movies.

Here’s the link to the complete DGA interview:

http://www.dga.org/Craft/DGAQ/.....Nolan.aspx

It is a shame that the medium of film is disappearing, despite its more visceral aura. I was talking with my two younger brothers today as they discussed the potential success in selling cinnamon rolls to earn money. My seventeen-year-old brother mentioned that it would be a success because people like to go get breakfast in this down economy. I argued that this is not the case, but that maybe they should consider trying to earn money in ways concerning movie-going because that is what people tend to do to temporarily escape the pressures and hardships of life. The key words here are “escape” and “life.” This article has caused me to think about this further and that the aesthetics of film enhance this escape from life. Part of the perks (as many consider them) of digital is the its indexicality to how things look and sound, its closeness in representation of reality, as scholar Arild Fetveit defines it in his article, “Reality TV in the Digital Era: A Paradox in Visual Culture?” In my view, a more satisfying escape from the reality of life does not involve a close representation of reality, but rather a representation of it that is more unsubstantial, even through aesthetics.

Moreover, it is unfortunate that distributors now have such extreme control over digitally projected content in terms of on how many projectors the video can be projected on and the times between which one can project the video. However, I too concede that film is quickly becoming obsolete and argue that many push aside the thoughts of pointlessness in switching over to digital because people enjoy the indexicality of the digital medium. Yes, the fact that manufacturers and the production industry have economic interests in the matter largely contributes to the switch from film to digital. However, audiences play a role as well, for they have to be interested in and willing to pay for movies shot digitally in order for manufacturers to earn money. Thus, although the visceral feel of film is an aspect that digital movies will never be able to genuinely emulate, we must embrace the notion that digital is taking over. This is not to say that everyone should get rid of everything they own related to film, but we should bear in mind that film projectors are becoming scarcer and that people will soon not be able to use film-related equipment, at least not for what it was used for in the past. This is not only due to those who now have much control over exhibition from afar, but also the large numbers of viewers who have embraced and paid for digitally shot movies, whether they are aware of it or not.

Pingback: Week 12: Where in your profession does the digital divide lie? | Digitally Amanda

In April 2014, Alain Robbe-Grillet’s L’Immortelle (1963), mentioned in the article above, was finally released on DVD and Blu-ray – but it still isn’t the same thing as seeing the film projected on a theater screen in 35mm, using the services of an excellent projectionist with top-tier equipment. Yet, as I write this in late August 2024, everything else I wrote above is still true. Digital has overwhelmingly won, though movies shot on film still exist. But everything winds up as a DCP – no one, other than archives, museums, and a few specialist “niche” movie houses have 35mm anymore.