Television studies, new media, and the divided curriculum

Graeme Turner / University of Queensland

I wonder if anyone else in media studies is bothered by this. The following comments are provoked by what seems to me to be an increasingly institutionalised split within the field of media studies: a division between the analysis of ‘old’ media and ‘new’ media. While this division is becoming increasingly embedded, and notwithstanding earlier arguments suggesting the need for a Media Studies 2.01 to make it an even more formal division, I think it is important to acknowledge that this is a split that doesn’t help us see the histories and the continuities that enable us to understand both the development of media technologies and their uses. In practice, it has to be said, what is offered up as the difference between the old and the new is often relatively arbitrary; even when the same content is consumed over a variety of platforms only some of them are thought to be ‘new’. So, to give an exaggerated but illustrative example, it would not be surprising to find that when the same television content is viewed via broadcast, cable or satellite it is regarded as old media, but when it is downloaded online it is new media.

My particular concern here is with how this bifurcation of our understanding of contemporary media has found its way into teaching programs in the universities. It is not uncommon now to see degree programs dealing only with digital or new media, without much interest in the continuities which link media platforms and histories nor, at times, in the underlying industrial structures upon which the production of their content is based. Although there is plenty of talk about media convergence, the fact is that there are now quite substantial differences in the ways that new media and old media are typically taught. Historically, television studies has been strongly focused on understanding its texts and genres, its industrial or policy structures, and television’s local or national functions as a media institution. New media studies have been less interested in content and more interested in the technological capacities and affordances available; and from these, there is an interest in mapping the possible shifts in the power relations between those producing and those consuming media, particularly those resulting in the customization of consumption and the production of user-generated content. In general, it would be fair to say what while television studies has been largely focused on content and its uses, new media studies is about technology and its uses.

Both of these approaches have their place, of course, but the separation of the field into programs of television studies, on the one hand, and new media studies, on the other hand, obscures how close they are to each other in practice—industrially, textually, and culturally. While media studies needs to be able to talk in an informed way about both ends of the spectrum, it also needs to be able to provide an account of the spectrum as a whole.

So, how should a contemporary media studies curriculum accommodate these differences? At present, that question doesn’t appear to be asked very often. Instead, small sub-fields are emerging which talk about the importance of understanding media convergence while, nonetheless, focusing most of their attention on highlighting what is distinctive about just one element of the media landscape. The excitement generated by the surge of innovation and change within new media has encouraged the development of topics which reinforce this tendency. Repeatedly, we see the commission of one of the fundamental mistakes in media history, which is to imply, or indeed to argue explicitly, that the new technology will inevitably displace the old (hence the coining of phrases like ‘heritage media’ or‘legacy media’). The hunt for the new, with its attendant penchant for futurism – of predicting how each new media capacity is going to ‘change everything’ that we do with media —has become a bit of an academic sport in the field of media studies as well as in the media itself: trend-spotters compete with each other to come up with newsworthy predictions of media futures. The danger in this, for the teaching of media studies generally, is that it commits the error of implicitly privileging the emerging technologies while underplaying the importance of the contexts into which they are being introduced, and the behaviours of those who use them.

These contexts, and their attendant cultures of use, are complicated, and mostly they involve a combination of both old and new media. Convergence has been a useful concept but in some applications it has worked as a label which enables us to overlook these complications; but they need to be unpacked and examined more closely. Let us think, for instance, about one example where emerging consumption practices have been influenced by very different affordances that come from both old and new media – the practice of binge viewing, of watching multiple episodes of the one program either via boxed sets of DVDs on television or computer screens, or through downloads. What makes this practice possible and attractive includes not only access to broadband and (increasingly) wireless, and with it the capacity to download whole episodes of network television via online providers, but also (for instance) the development of high definition digital TV, the availability of large flat-screen television sets and the increasing occurrence of the home theatre or ‘media room’ as a feature of the suburban home. The industrial base for these new zones of consumption, and the content they consume, however, is an industry aimed primarily at producing content for network television. Episodes of Homeland may be downloaded and viewed independently of a live viewing schedule, so they are seen on computers and portable DVD players as well as in the ‘media room’, but they were produced and financed through the television industry. If we focus only on the shift to the downloading of such programs, without noting the parallel increase in the consumption of TV content on DVD for instance, we could conclude that the television set has been displaced as a platform of distribution. And this might encourage us to argue that television is on its last legs – even though it is the television production industry which makes the downloaded material possible in the first place. It is an argument that has often been made, of course2, even though we know that in many countries, including the US, people are now spending more time watching TV than ever before.

As new programs in digital media, new media, or multimedia proliferate, and as television continues to find itself tarred with the brush of heritage media, it is time there was a more concerted effort to integrate these two aspects of our media curriculum so that we are able to talk about them in ways that understand them both accurately, as important elements within a multifaceted and interconnected ecology of media systems, rather than a linear series of mutually exclusive evolutionary developments. A media studies curriculum which took a longer view of media history, while resisting the temptation to continually predict our media future, might help to deliver that understanding.

Image Credits:

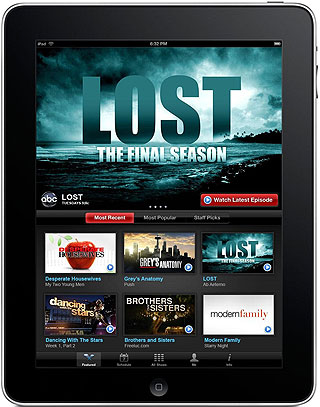

1. Old Media and New Media

2. Old Media on New Media

Please feel free to comment.

- While I want to acknowledge the debates around David Gauntlett’s proposition of Media Studies 2.0, I want to focus my comments slightly differently – upon the problems this situation raises for the discipline or field of media studies as it is presently constituted. [↩]

- I have argued against this line elsewhere, the most extended is in G.Turner and J.Tay (eds.) (2009) Television Studies after TV: understanding television in the post-broadcast era (Routledge, London and New York). [↩]

Well your topic is unique and I really liked it thanks for sharing good information about it I was looking it over Google.

how to copyright something

thanks admın very nice…

thanks admın very nice…

This is a compelling and well-articulated presentation of questions arising in media studies that seems obvious, but difficult to articulate and answer. I agree that the metaphor of an “interconnected ecology of media systems” is more useful, and accurate, than simple evolution. But evolution takes place within an ecology. When one adds cinema, video games and other emerging interactive media to the home entertainment ecology, it grows ever more complex, and, most importantly, its evolutions uniquely harnessed from consumer to consumer. The idea in this post seems to be that television content, produced by networks, is what defines television, what pervades the ecology, regardless of how it is viewed. While television content may always be television, these emerging zones of consumption do not always consume it, and media studies must approach them from this perspective as well, although a division into “old” and “new” is not, as this post points out, very helpful. I would venture, instead, that the existence of an ecology of media systems argues for an ecology of media content, and there’s no guarantee that the industrial base will remain network television.

Thank you for this insightful and engaging analysis. I agree that a divided curriculum is unwarranted, and that combining studies of old and new media in university programs have proven to be a necessity. However, I’m not sure that the “penchant for futurism” has to be discarded in order to do this. Rather, aligning the historical with both the present and the future could serve to ameliorate “the error of implicitly privileging the emerging technologies.” That is, within the larger umbrella of media history – the evolutions of content, technology, business and consumption practices, for example – could be woven studies of new and projected technologies. I take this integrative viewpoint for a very specific reason.

Quite simply, knowledge of history provides a more focused understanding of the directions that media industries are headed. The major deregulation of television policy in the 1980s, a trend which helped to end the Network Era, motivated a dramatic increase in amount of available content and the number of forums by which that content could be distributed. This growth has only been amplified in the thirty years since, and media now operates in a state that television cannot possibly be expected to keep up with: a physical television set no longer carries the weight and ubiquity it used to, as either entertainment or news sources. Using this model – the combination of past and present conditions, in conjunction with a specific technology – a media scholar could predict future outcomes, if he or she were so inclined. For this particular example, the researcher might outline the ways consumers will move on from the television, or the ways developers might adapt the technology of the equipment, in order to suit changing lifestyles, desires, and social mores.

The integration of historical context and emerging technologies may not be right for every scholar, and I can appreciate the desire to leave studies untouched by excitement over the new and the shiny. However, I can also imagine a scenario where the thrill coexists with the academic, where the two need not be mutually exclusive. And here I see an opportunity to take “a longer view of media history” while also looking ahead to “predict our media future.”

Interesting. I would agree with this position of this article insofar as media studies is indeed very good at setting up false dichotomies which are insufficient for looking at the actual way media is consumed. When you describe the paradigmatic half-step of looking to digital distribution while ignoring the more conventional 20th century distribution of DVDs, you’re definitely highlighting some pervasive, myopic thinking.

That said I was disappointed that your article did not go further. It feels like an excellent prelude to a much larger discussion we have yet to have, concerning the holistic way in which 21st century technologies and viewing habits interrelate. You also barely seem to touch upon the role of unofficial distribution channels such as illegal streaming websites and torrents– obviously, overplayed by media companies for their impact on profits, but nevertheless a useful aspect to the conversation when discussing media properties which lack official digital distribution channels.

For example, the large internet-based fandom which has sprung up around My Little Pony: Friendship is Magic, a show for which comprehensive DVD sets are not likely to ever be produced, continue to stream the show illegally in large numbers and create their own home-made DVD sets. Equestria Daily, the show’s major fansite which has been acknowledged by rights-owners Hasbro (being mentioned in show ads, granted exclusives, etc) continue to link illegal streams in addition to linking to the official iTunes download pages. Moreover, because the network on which the show airs is exclusive to digital cable and satellite subscribers, we encounter a class and regional barrier to viewing the program in the manner intended. It seems to me that any deep investigation into the intersections and tensions between “old” and “new” media will have to go further than the popular programming of major networks and into these marginal communities, which really do frequently reflect the “futurism” promised in some of these more optimistic new media studies approaches.

It is a cliche to bring up Jenkins in these circumstances, but as he says in riffing on McLuhan, “contact is king.” This can refer to contact between viewers, but also between content and consumer. To what extent are format and availability inflections on viewing practices? Are viewers more likely to binge view a short-lived cult series, like Firefly, over a successful mainstream hit like The Office? I don’t have any data on this– but I think your remarks here are an excellent preamble for these kinds of questions.