Mining Collective Memory: Fairytales grow up, take their shirts off

Camille DeBose / DePaul University

In my inaugural article for Flow I wrote from the viewer’s perspective. I wanted to discuss the television show Pretty Little Liars as one who consumes media, through the Bourdieusian lens of “universalized particularisms.” For this current article I’d like to forge ahead in discussion as one who produces, media in general and film in particular, highlighting the intentional ways we, as producers, mine collective memory. The symbolic use of color, for example, is made possible by the previous cultural definition of green as youthful and vibrant or red as lustful or dangerous, passionate or sinful. The tone, pitch and tempo of the music playing from one scene to the next is significant, deliberate and some would say, fifty percent of the film going experience. I should also mention the specificity of the chosen shot. It will be long, medium or close depending upon the level of intimacy the filmmaker wants the viewer to experience. These strategies are employable because of our collective understanding of visual language. They are also logistic or perhaps, objective. I was recently interested in the subjective mining of myth and fairytales when earlier this year two films were released within days of each other.

In March Beastly and Red Riding Hood made their debut. Beastly, a loose adaptation of the novel by Alex Flinn which loosely adapts the original story credited to Jeanne-Marie LePrince de Beaumont, tells the story of a laughably vain young man cursed by a witch played by one of the Olsen twins. We’re introduced to Kyle as he goes about his morning ritual of topless pull-ups and various other exercises. The camera frames him tightly in medium and close shots as he rises and falls in the frame. Intimate. This display segues to a student government debate in progress wherein Kyle confesses he has no real interest in the issues. He cockily admits the victory will garner points on his college applications and people should vote for him by virtue of his good looks alone. The crowd of high school students roar their assent. Amid the clapping and cheers, his seemingly meek, yet quirky and attractive opponent Lindy takes it in stride and keeps on keeping on. At this point we know what to expect. Beauty and the Beast, thanks in part to Disney, is a story firmly entrenched in our collective memory. I’m speaking in reference to “collective memory” as operationalized by Maurice Halbwachs1 in his work On Collective Memory (1992). This memory, constructed and shared by the group (society) is fed by the consistent reproduction of particular images and stories. Thus, the proliferation of storybook copies, dvd releases, soundtrack updates and fast food tie ins ensures that even for those who have never read the book or seen an animated rendition are still familiar enough with the content of the story to understand the reference this film makes.

We are now primed and ready for the pretty boy to become ugly and the removal of the curse to be “true love” and for the most part, this film stays true to the spirit of the fairy tale. The pretty boy does in fact become… strange looking. The witch declares “true love” as the cure and the down to earth damsel struggles with issues related to her father right up until the happy ending. The movie works because of what we already know. We expect the conveyance of the curse in response to the displayed vanity and aggression. We accept Kyle’s blossoming tree tattoo and chuckle when it twinkles with Christmas lights. We also know the ending. There is no mystery here. The “prince” will be cured upon his honest repentance, of this we have no doubt. The value in this story, and perhaps one of the reasons it remains in our collective memory, is the lesson warning us of inner ugliness and the danger of ending up unloved. Ultimately, this contemporary retelling of Beauty and the Beast is consistent with our cultural collective and also works to reinforce existing notions. Its cinematic kin Red Riding Hood, is altogether a different kind of beast.

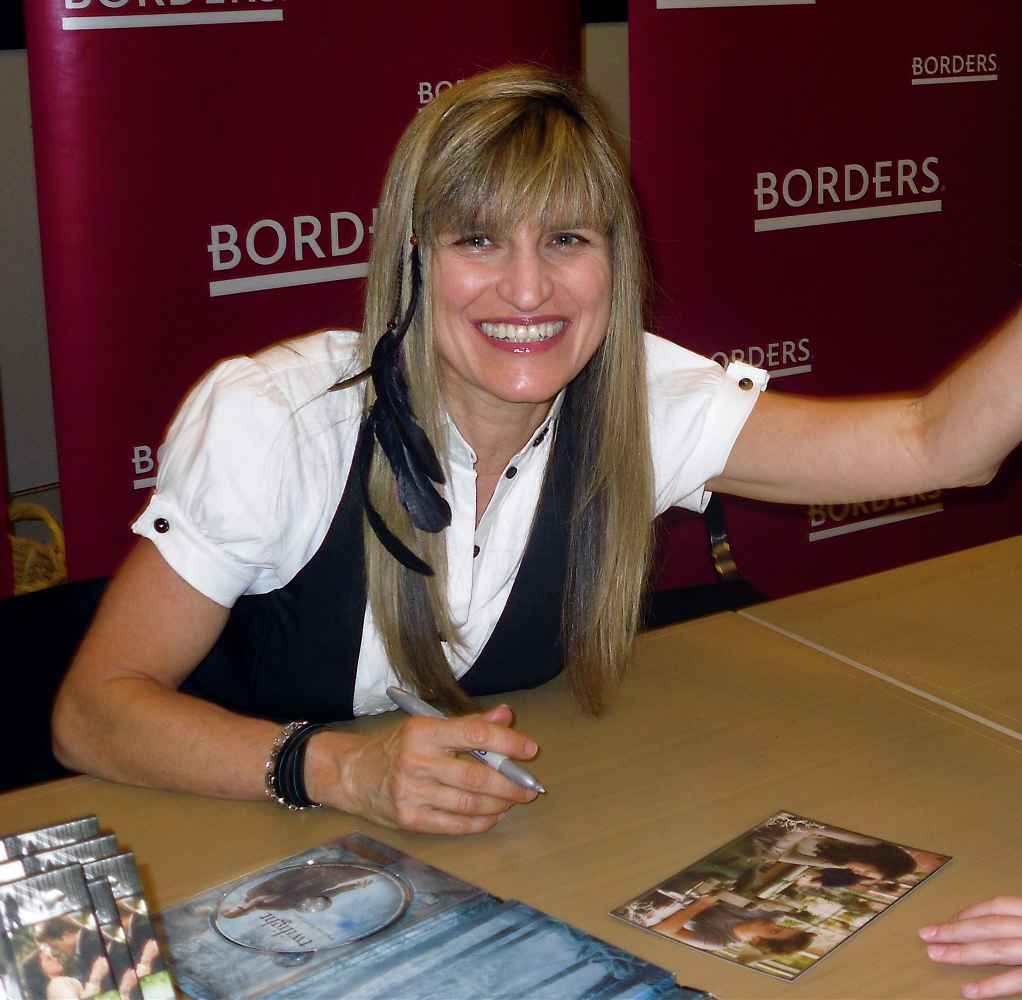

There are various designations for films. Some are “based on a true story,” and some are original screenplays. Some are “faithful adaptations”, meaning they make every attempt to reproduce the source text. Others are loose adaptations whereby the “spirit” of the source materiel is maintained while creative liberties are taken with other aspects of the film. Time, for example, could change to contemporary New York instead of England in the middle ages. Location can be modified. Perhaps we can set the Little Mermaid in space and have her fall in love with an astronaut. Regardless of creative decisions, the core of the story remains. Catherine Hardwicke’s Red Riding Hood falls under the category of “inspired by.” This is the loosest of the loose with respect to adaptation. Here, Hardwicke mines collective memory seemingly for the sole purpose of creating a “hook.”

Hardwicke is, of course, no stranger to heady, teen fare. Best known for directing the first film in the Twilight series, at 55 she seems poised to claim a position in the hallowed halls of teen hollywood. Somewhere in the blogosphere she was referred to as “Anne Rice with a camera,” which didn’t seem to me to be a compliment. While I’d like to give you a synopsis of the film I’m not sure I can. Tangents shot out from the screen like so many branches of a tree. One thing that was clear was the existence of a forbidden love between Valerie (Red) and Peter the woodcutter. Valerie makes an enthusiastic effort to consummate that love but an arranged betrothal and the horrifying existence of a child eating wolf in the town foils her efforts. There is a strange post-slaying celebration scene that takes place after the townsmen kill a wolf that of course is not the wolf. The scene is punctuated by the bombastic and slightly orgiastic braying of Fever Ray, the lyrics of who’s song I have yet to decipher the meaning of.

“The Wolf“:

Eyes black, big paws and

Its poison and

Its blood

And big fire, big burn

Into the ashes

And no return

Woooooooooooooooooooooo (X4)” (Fever Ray 2010)

The film bears almost no resemblance to the classic tale which begs an interesting question. When using source material that exists in the collective cultural consciousness does the filmmaker owe a duty of care to treat such material gently? By “gently” I mean, should there be some recognizable thread running through the story which the viewer can clearly tie back to the source? In Hardwicke’s piece there is only a girl with a red cloak and a wolf that isn’t a wolf but a werewolf. While watching the film (my mind wandered a bit) I found myself intrigued by the question of why the filmmaker felt satisfied with reducing the essence of the tale down to an article of clothing, the symbolic use of red as arousal and a mythical beast. I also found myself wondering about the appropriateness of appropriating stories collectively understood as being “for children” in the way Hardwicke appropriates Red Riding Hood. Could I decide to give the Little Mermaid her first sexual experience? Taking from collective memory, for a filmmaker, is an interesting and perhaps tricky endeavor but there is also the consideration of how we add to the collective memory. When we modify these stories, do we inscribe them anew for each subsequent generation? If so, is that a good thing or a bad thing? Does the malleable nature of collective memory call out for a gatekeeper or do its shifts and ripples simply indicate an evolving collective cultural consciousness?

Image Credits:

1. Alex Pettyfer

2. Red Riding Hood

3. Catherine Hardwicke

Please feel free to comment.

- Maurice Halbwachs: On Collective Memory, Univ of Chicago Press, 1992 [↩]

The questions that you raise at the end of this article are thought provoking ones, and particularly prescient now in a year when there are at least two television versions of Beauty and the Beast in pilot stages, two film adaptations of Snow White and the Seven Dwarves about to battle at the box office, and the release of teen phenomenon The Hunger Games, which, to put it generously, borrows (whether intentionally or not) from the Japanese film Battle Royale, and seems poised to spawn a mythology or at least an understanding of teen cinema of its own. Storytelling is rarely (if ever) a ‘pure’ creative exercise that borrows nothing from previous stories or mythologies, but it seems incredibly bizarre that there would be so many pairings of texts that explicitly rework particular fairy tales, and do so in competition with one another, at the same time.

The ways in which we rework fairy tales and narrative mythologies – whether we’re adapting them straightforwardly or more ‘loosely’ – create spaces in which to investigate what elements of our culture are likewise in flux or unstable. As such, I’d like to propose some additional questions: Why is it that we’re returning to such explicit adaptations of fairy tales right now, in 2011/2012? What relation might these particular stories have to contemporary social politics and economics at home, and the circulation of media texts and communications at a global level? Furthermore, what is ‘accomplished’ by making versions of these fairy tales that are aimed at the teen viewer, or geared towards adults through even more violence, sex, loose adaptation and the showcasing of celebrities like Charlize Theron? What can we deduce about the interconnecting film and television industries that teen- and adult-oriented adaptations are being released simultaneously and poised to compete against one another? And finally, how do comparisons of these fairy tale adaptations, both textually and industrially, reflect the malleability or consistency of collective memory?

Society’s collective memory is without a doubt a powerful means to draw audiences into a television story or filmic story and you highlight the collective memory of fairytales nicely. Like Alana I immediately thought of the of the new Snow White movies punched with star power which are debuting in the coming months. Additionally, the television series that began airing this past fall on ABC, Once Upon A Time, plays on notion of society’s “collective memory” specifically the memory with tales engendered with Disney and the Brothers Grimm. Once Upon A Time appears to be a hyperbole of the spinoff as it brings in a number of stories and characters from our collective memory and then weaves them together into something new including but not limited to: Snow White and the Seven dwarfs, Sleeping Beauty, Maleficent, Fairy Godmother, Jiminy Cricket, a Genie from Agrabha (Aladdin), Rumpelstitlskin, and Beauty and the Beast. This new packaging is displayed at the onset of the series. The pilot episode begins with a black screen and text that reads,

The show includes iconic images and sounds that are distinctly embedded in our memory (for example, in the pilot Prince Charming kisses Snow White who is dead in a coffin the woods surrounded by the seven dwarfs, and she is brought back to life by true love’s kiss), but then looks to dismantle them and add complexity to them. The narrative is two fold on of character development, which takes place in the enchanted forest, and the other is the real world of Storybrooke, Maine where these characters have been exiled to and our stuck (no one can leave or else something bad will happen to them) because of a curse. However, as part of the curse the people of Storybrooke have no memory of a life outside Storybrooke.

What is interesting then is not just the collective memory of the fairytales at play in the series, but the other narratives and collective memories Once Upon A Time has chosen to suture in with specific female leads. Obvious biblical references surface quickly Emma Swan (the daughter of Charming and Snow) is the savior character who is the only one who can break the curse. Her mother, Snow White in the enchanted forest is a school teacher in Storybrooke whose name is Mary Margret. Her name Mary could point to Mary from the old testament who is gives birth and is the mother of the savior, or Mary Magdalene who is a both a harlot and a worshiper and recognizer of Jesus as savior in the Old Testament. In any case there is a specific relationship with Mary (mother, God?), and Emma (Daughter, Savior) picked up. Snow hides Emma so she is saved from the cures in essence She sacrifices her only child, so she can save the world. Charming and Emma who sacrifice their child as the only way to save each other and the world, so this self-sacrifice possibly positions and aligns them as ‘God’ then (although this isn’t used and played out in the series). Fairy tale adaptations/hybridizations seem to reflect the fluid nature of collective memory.

This is a compelling account of the ways existing narratives are maintained in collective memory so that they can become part of the language at a media creator’s disposal, along with conventions of shot design, color, and spoken English. Many of the questions DeBose raises, however, seem strongly influenced by the quality of her two examples. Ultimately we judge an adaptation – like any other work – by its originality and power. If Red Riding Hood had turned out to be a great film, our discussion of its relationship with the source material might be very different.

DeBose suggests that, “Hardwicke mines collective memory seemingly for the purposes of creating a ‘hook.’” Certainly there are crass, commercial motives for the creation of derivative content, whether sequel, spinoff, or adaptation. But it might be more generous to the architects of a project like Red Riding Hood to consider the appeal the source material might have for them, as well as for their intended consumers. Creators of content share in the zeitgeist just as audiences do. The robust resurgence of fairy tales in the months since DeBose’s original post that Romoff and Levy identify has the potential, at least, to produce content of intellectual, aesthetic, and social merit.

The danger of adaptation lies in reliance on source material to the detriment or exclusion of efforts to craft something that can stand on its own. Todd Gitlin attacked this tendency in the television industry in his 1983 monograph Inside Prime Time. In Gitlin’s view, much contemporary network television was “simply bad – inert, derivative, cardboard – because no one with clout care[d] enough to make it otherwise” (84). It would be hard to argue that the trend Gitlin deplored – “the triumph of the synthetic” (63), in his formulation – has not played a persistent role in media creation in the intervening decades.

In this sense, I find Gitlin’s account, and DeBose’s, persuasive. Recycling content comes with major pitfalls. But I’d hesitate to attribute the failure of a particular work to the method of its engagement with collective memory.

Source: Gitlin, Todd. Inside Prime Time. New York: Pantheon Books, 1983, 1985.

As both Alana and Rosie have noted, the relationship between fairytales and “collective memory” seems like an especially pertinent subject matter at a time in which the film and television markets are inundated with fairytale remakes. Like Jesse, I began to think of this trend specifically in terms of the industrial practices of Hollywood, which, as always, is searching for new (or renewed) sources of pre-branded entertainment. With superhero cycles and occult franchises (vampires, werewolves, witches, etc), appearing to have reached a saturation point in the market, or, perhaps more importantly/accurately, with studios running out of quality source material to supply these trends, industry executives and talent have been searching for other reservoirs of “collective memory” to exploit.

In the current media landscape, fairytales are ripe for reinvention. As Camille points out, thanks in large part to Disney animated films, from Snow White (1937) to The Princess and the Frog, (2009) fairytales have seeped into our collective memory. While these stories, in various iterations, have peppered the media landscape throughout the past two decades [e.g. Ever After (1998), Ella Enchanted (2004), Enchanted (2007), the Shrek franchise (2001-2010)], they have not loomed as large in the cultural zeitgeist as during the Disney princess cycle of the late 1980s/early 1990s [The Little Mermaid (1989), Beauty and the Beast (1991), Aladdin (1992)], which coincided with the rerelease of older Disney fairytales on VHS as part of the Disney “Classics” collection [e.g. – Sleeping Beauty (1986), Alice in Wonderland (1986), and Cinderella (1988)]. This confluence of theatrical and video releases of nearly all of the Disney fairytale collection in the span of one decade made Disney the (American) authority on the fairytale at the end of the 20th century.

Now, with the success of Disney’s own live action version of Alice in Wonderland (2010), other studios are hoping that enough time has passed that they will be able to cash in on our collective memory of Disney’s fairytales while altering the stories, both in order to appeal to larger audiences and to avoid copyright infringement. Excluding Once Upon a Time, which is produced by Disney affiliate ABC, this current wave of fairytale movies must eschew any changes Disney made to the “original” source material, relying instead upon those versions that are part of the public domain. As a result, many of these new films are derived from a previous “collective memory” of fairytales defined by the Brothers Grimm stories. In contrast to the kid-friendly, sanitized, and optimistic Disney versions, the Grimm stories are, well, grimmer; they are dark, violent, cautionary tales. It’s too early to tell whether this reversion to the darker tales of the past will supplant the “collective memory” of the Disney fairytales, but it points to the amorphous nature of the fairytale form and, as Camille suggests, the malleability, and also the forgetfulness, of “collective memory”.

To return to Camille’s discussion of Red Riding Hood, while there is no Disney precedent to the Little Red Riding Hood fairytale, and the Catherine Hardwicke film is certainly a loose interpretation of any previous iteration of the story, tracing the origins of the “classic tale” likewise points to the difficulty of delineating an original text to which modern interpreters might or should adhere. According to Bruno Bettelheim in The Uses of Enchantment, though the Grimm brother’s “Little Red Cap” is perhaps the best-known version of the story today, the title, “Little Red Riding Hood,” actually comes from an older version of story by Charles Perrault, published in 1697 (Bettelheim, 167). As Bettelheim points out, Perrault’s version is darker than the Grimm story (the little girl dies in the end) and has an overtly sexual tone, but he traces the origins of the story even further back, to tales darker still (167). He points “to the myth of Cronos swallowing his children, who nevertheless return miraculously from his belly,” and to “a Latin story from 1023 (by Egbert of Lieges, called Fecunda ratis) in which a little girl is found in the company of wolves” and “wears a red cover of great importance to her” which scholars have claimed was “a red cap” (167).

Each subsequent iteration of the story has been a departure from the tale that came before, each adapted to its own time and the needs of its interpreter. But this type of modification is closely aligned to what Bettelheim points to as the value of fairytales for children. He argues that in order for a fairytale to be successful it must have “meaning on many levels” so that a child may continue to find meaning in the story as he grows (169). He writes, “Only when discovery of the previously hidden meanings of a fairy tale is the child’s spontaneous and intuitive achievement does it attain full significance for him. This discovery changes a story from something the child is being given into something he partially creates for himself” (169). Perhaps it is precisely our ability to alter these stories to fit our needs, our ability to “inscribe them anew,” that makes them fairytales.

Bettelheim, Bruno. The Uses of Enchantment. New York: Vintage Books, 1975.