Bootleg Archives: Notes on BitTorrent Communities and Issues of Access

Iain Robert Smith / Roehampton University

Since the early years of VHS, a limited grey market has developed around films which are not available to buy through legitimate channels — a market that has expanded considerably with the advent of peer-to-peer filesharing on the internet. While much of the scholarly debate around filesharing has focused on the downloading of the latest films and TV shows, I would like to use my first column to argue that it is time we pay attention to the vast range of previously lost and forgotten films which are being circulated through paracinematic BitTorrent communities.

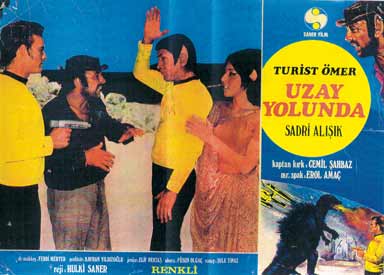

Before I get into the wider implications of this phenomenon, I should acknowledge that these communities have benefited me as a researcher. The topic of my PhD research — global film adaptations of American popular culture such as the 1966 Filipino film James Batman and the 1973 Turkish remake of Star Trek1 — meant that I was working on a large number of films which have never been given an official release on VHS, let alone DVD. For a long time, the only way to access these films was by trading nth-generation dubs with fellow collectors.

What has changed in recent years is that private BitTorrent communities such as Cinemageddon and Karagarga are allowing these amateur archivists to share their collections online and thereby make them freely available to all who have registered with the tracker. In doing so, these communities have developed informal bootleg archives with tens of thousands of rare and hard-to-find titles available at the click of a mouse.

Now, various scholars have debated the ethics of filesharing and I don’t really want to focus on those debates here, although perhaps that may be something for the comments. Instead, what I’d like to consider is that these informal networks of collectors are sharing material that has been otherwise inaccessible, fansubbing material which has been unavailable with subtitles, and, thereby, are potentially reshaping our understanding of underexplored areas of world cinema history.

Given that Anglophone scholarship on national cinemas has been largely focused on films which have gained some form of international distribution and been subtitled in English, one of the strengths of these online communities is that they function to widen access to areas of world cinema that do not tend to leave the domestic market. As Dina Iordanova has recently argued, “we operate with a flawed understanding of the dynamics of world cinema, and… the field of film studies would greatly benefit from the introduction of more acute peripheral vision.”2 From the most obscure Italian giallos through to even rarer 1970s Turkish action films, private BitTorrent trackers such as Cinemageddon and Karagarga are offering a library of peripheral titles which are otherwise near impossible to track down. According to Karagarga’s manifesto, they are focused on “creating a comprehensive library of Arthouse, Cult, Classic, Experimental and rare movies from all over the world”3 and with nearly 60,000 titles available they are getting increasingly close to that goal.

Of course, in many ways this is nothing new. For a long time, the bootleg market has offered an alternative to the mainstream channels of film distribution. Ranging from films which have been banned from distribution through to films which have simply never received any form of official release, the trade in bootlegs has played a role in providing access to films which would otherwise be inaccessible. Often relying on a broad interpretation of the Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works, traders such as the now defunct ‘Superhappyfun’ would provide films to collectors with the proviso that, “If a film should become available domestically, or if another seller should offer a better copy, we immediately stop offering it to our clients.”4

What has shifted, however, is the sheer scale of material being traded, and the ease of access that is being provided through the P2P networks. As William Uricchio has observed, “P2P networks thrive in a dehierarchized, decentralized and distributed organizational environment and require collectivity and collaboration as conditions of existence.”5 Given that a dedicated group of people are working on tracking down rare films, translating the dialogue and creating fan-subtitles for the community, this reflects what Henry Jenkins has described as the “collective intelligence of media fans”6 whereby fans are using new media technologies to archive, appropriate and recirculate media content.

We should be wary, however, of seeing this simply in terms of a utopian participatory culture. Too often debates around filesharing position pirated films as a form of resistance to global media conglomerates so that the “waking nightmares of Hollywood honchos swiftly become swashbuckling adventure stories.”7 Instead, what we have with these BitTorrent communities is a more ambivalent dynamic in which the trackers are providing access to rare or unavailable material but the creators of the films — who are often as far from Hollywood as can be — are not getting any financial support. There is also the further problem in that the availability of bootlegs can potentially make it uneconomical for distributors to license and restore films for official release.

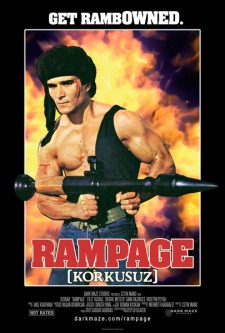

I would like to end therefore with the example of Korkusuz (1986), a Turkish reworking of Rambo (1982) which was released on DVD by Dark Maze Studios in 2009 under the title Rampage. Licensed from the filmmakers and provided with a new English language track, the film was uploaded to BitTorrent sites within two weeks of its release. Upset that his DVD was being pirated, Dark Maze head Ed Glaser asked to have the film removed from BitTorrent communities, arguing, “Look, I am not ‘The Man.’ I have a full time, regular day job that supports my ability to make films. People who pirate my movies are not sticking it to anybody. They’re just robbing someone of his dream to make a living doing what he loves.”8 The comments were not heeded, however, and the film continued to be shared online for free.

Ultimately, then, with home distribution shifting towards a streaming model that potentially closes out whole swathes of film history,9 these filesharing communities offer a makeshift archive of rare material that provides access to films that might otherwise be forgotten. As the example of Korkusuz indicates, however, while these communities are providing access to rare and obscure material, there are still a number of ethical issues surrounding this model of sharing that are yet to be resolved.

Image Credits:

1.The Pirate Bay

2.Turist Ömer Uzay Yolunda (1973)

3.Korkusuz (Rampage, 1986)

Please feel free to comment.

- For further discussion of this film, see Iain Robert Smith, “Beam me up, Ömer: Transnational media flow and the cultural politics of the Turkish Star Trek remake” Velvet Light Trap 61 (Spring 2008) [↩]

- Dina Iordanova, “Rise of the Fringe: Global Cinema’s Long Tail” in Dina Iordanova, David Martin-Jones and Belen Vidal (eds.) Cinema at the Periphery (Wayne State University Press, 2010) p23 [↩]

- See the full manifesto at http://karagarga.net/manifesto.php [↩]

- ‘Superhappyfun’ as cited in Jonathan Rosenbaum, “Global Discoveries on DVD: Ambiguous Legalities, Gambles, Lucky Breaks, and Box Sets” Cinemascope 21 Available at http://www.cinema-scope.com/cs21/col_rosenbaum_dvd.htm [↩]

- William Uricchio, “Beyond the Great Divide” International Journal of Cultural Studies 7:1 (March 2004) p87 [↩]

- Henry Jenkins, “Interactive Audiences? The ‘Collective Intelligence’ of Media Fans” in Henry Jenkins, Fans Bloggers and Gamers (NYU Press, 2002) [↩]

- Barbara Klinger, “Contraband Cinema: Piracy, Titanic and Central Asia” Cinema Journal 49:2 (Winter 2010) p107 [↩]

- See Ed Glaser’s full statement at http://www.darkmaze.com/post/a-message-from-ed [↩]

- As Wheeler Winston Dixon discussed in his FLOW column on June 9th [↩]

I find the use of labels of the “grey market” of this type of film distribution via torrents as a “market” problematic. Does it slap a label that harks more to capitalism and monetary distribution with the forces of competition that falsely supersedes the already avoided discourses of “ethics of file sharing”?

I’m curious who Ed Glaser put out his request to, as within the P2P online ecosystem very few sites have a customs and excise system like CG (and a few other private sites).

It would seem odd to me that, having been requested to make a particular title unsafe, CG would continue to include it on their site. I would say that the internet as a whole is like the Wild West, with very few laws that are obeyed and very few morals upheld. CG and similar sites are like outposts on the edge of a town, a little more refined than the rest, and not just any stranger is welcome.

What’s interesting today is that there is spill-over occurring with public and semi-public sites (like Demonoid), where fansubbed and obscure films are being made available there as well. I’m curious if you think that might be a detriment to the community around sites like CG (where often people request their uploads not be upped on other sites as well)?

There’s a snobbery involved in some ways, but mostly it’s a privacy issue from members of a site who know they are all breaking the law, but feel is it justified due to the rarity of material shared. Once that becomes a part of the mainstream torrent community, the attention is magnified and there is a fear that too much attention can never be a good thing. And after all, it is the members of private sites who often take the time to rip their VHS tapes and upload them, and then other people upload those files to public sites (sort of like 3rd generation piracy). Do you think that private trackers have inherently more “respect” for the material they host, and that private trackers are sort of a free-for-all? And therefore by extension, should the films you’ve mentioned here be kept off of public trackers, lest a DVD release comes out and is swiftly ripped?

Typo….what I meant to ask was:

“Do you think that private trackers have inherently more “respect” for the material they host, and that PUBLIC trackers are sort of a free-for-all?”

Thank you for your comments!

Simon, that is a very interesting point about the appropriate use of “grey market.” It’s a term which was often used to discuss bootleg trading in the VHS era and I was using the term to indicate that this phenomenon is part of a longer lineage. Yet, as you suggest, there are marked differences which certainly complicate the notion of a market now that people are predominantly sharing titles rather than buying a dub for $10 (although we used to trade VHS titles with no monetary exchange back then too). Of course, as examples like Ed Glaser’s Korkusuz/Rampage release indicate, these BitTorrent communities still have an impact on the market for licensed releases.

Dax, I don’t want to get too much into the specific details of Ed Glaser’s case although you should have a look at the comment from the admin ‘Anonymous’ on his blog entry http://www.darkmaze.com/post/a-message-from-ed/ as it captures some of that sense of ‘respect’ for the material which you describe. The film is still being shared on these private trackers, though, and the idea he puts forward that “You’re the guys we look up to, and the guys we SHOULD support” is not an opinion shared by all.

Also, you make an interesting point about public trackers starting to make these rare/fansubbed titles available beyond the private communities which originally shared them. While I agree that there is often more sense of ‘respect’ displayed for the material in the private groups, I’m not quite convinced that there is a significant ethical difference between sharing the same material on a public vs. private tracker. Nevertheless, I agree it would have an impact on the health of the private communities if people were predominantly sharing the films publicly.

Iain, Dax,

Thanks for the incredibly enlightening discussion. I am learning a lot here.

One question, though: having been to thse P2P and sharing sites, it bugs me that there is a certain skewing. Any lowbrow horror film ever released on VHS is in there, but when it comes to films such as ‘Un monde sans pitie’ there are notable absenses. I mention the title of the film and not the ‘category’ it belongs to because I believe the fact it falls in between categories is part of the point here. Part of me thinks this is a result of the US-centricness of such sites. With the term US-centricness I don’t mean American films, but rather films from all over the world with a certain appeal or status (or indeed a locked-in generic ‘place’) that is pre-existing to the website community in question. I believe the full catalogues of Jean Rollin and Jess Franco on Cinemaggeddon are exemplary of this – and just for the record I massively appreciate these).

I suppose the question here is: how do these communities not just duplicate (or reverse and thereby perpetuate) categorizations and hierarchies already established? And does it matter?

Just to add to the “grey market” discussion, there is the notion of private sites offering perks to those who donate money for server costs and upkeep. VIP status, which usually prevents a user from being banned for low ratios, is often obtainable by donating $20 or more. So there is still the idea of paying for the product, albeit in a much less direct fashion (and when added up, in a much cheaper way as well).

Although you’ll also find, on the more niche-like sites, “pots” that are created by amassing user donated money in order to buy material to share. For example, if someone has a complete set of self-taped copies of a television mini-series for sale on iOffer, that pot would go towards purchasing it, then making it available as a torrent for the site. So that’s fascinating as an example of community working to do the job of a single fan, using the internet and torrents as a means to take the burden away from the cost of obtaining the material.

I myself have offered to put up funds to have someone rip The Edison Twins off Amazon on Demand, to no avail. It’s a Canadian produced and shot show from the 80s, no longer on the air in Canada nor in print on VHS or DVD, yet Amazon on Demand restricts anyone not in the US from paying to view the show (of which it has the entire run of 100+ episodes). An interesting example of the boundaries facing cross-national sharing, and they ways fans circumvent them.

Thanks. Those are some really interesting comments and questions.

Ernest, I think the skewing towards pre-existing categories is certainly true of the ‘projects’ which trackers like CG use to collate films according to genre/director/actor etc. (like the full catalogue of Jess Franco you mentioned) but the vast majority of the titles on there are not actually part of the projects system. In other words, the tracker is populated with films uploaded by fans so this undoubtedly emphasises genres with pre-existing fandoms, but there are huge numbers of films (often uploaded by fans outside the US) that do not fit into the expected categories.

As for ‘Un Monde Sans Pitie’, this isn’t on CG (which is probably to do with the sense it doesn’t quite fit on a cult/trash cinema tracker) but it is on KG (which has more of an art cinema emphasis) and it is currently awaiting fansubbing.

Dax, that is a very good point about the use of donations on these sites and how there are still some market principles at play here. Having a collective pot of money to purchase rare material from collectors allows the group to track down ever more elusive films (sharing the cost among the group) and this has provided access to a much wider range of material than any single fan could have amassed themselves.

There is also the issue about what material is appropriate to share. To go back to your Wild-West metaphor from earlier, there are some attempts at self-policing on these private trackers (e.g. the customs/excise system on CG) but the lines are heavily contested and laws are not always followed. Cross-national sharing also complicates things here since the old rule of thumb was, “If a film should become available domestically… we immediately stop offering it to our clients” but these trackers have users around the world. To take your example of The Edison Twins, this isn’t available in Canada so many would argue that it is appropriate to share (given that it is not available domestically) but by sharing it on a tracker, this would then be available worldwide including territories like the US where you can already pay to watch it on AoD. In that sense, the onus of maintaining this ethical position shifts to the person who downloads the material being in a territory in which the material is not available commercially.

Very fascinating article and quite in accordance with my own interests on the topic. I enjoyed that you touched upon the internal morality of these sites and how they will often–albeit futile–cease distribution of these cult materials. The problem with the logic, as with the Internet, once there is pee in the swimming pool there is no way to get it out. These kinds of media will forever circulate in the either. Note: I am surprised you did not mention the similar construct of anime fan subtitle community organizations in relation to these websites.

We clearly fall into problematic issues of trade and ownership. Hence, all of the discussion of the “grey market” classification above in the comments. Perhaps more appropriately, this is the ever conflicting transaction between a gift economy and monetary economy. I would be interested to see more research go further into these kinds of underground groups within the darknet and their connection to bootleg economies and its relation to the idea of “the public right to ownership.”

I, myself, have become highly interested in the transformative nature of bootlegs, particularly within the realm of popular music and concerts. But also, in the more obscure archival importance of bootlegs such as lost theater prints, unfinished videogames, early program source code, and other forms of media that would have (initially) be of little interests with the dominant marketplace but highly valuable to academics and collectors. At times, even the release of such media becomes of concern to copyright holders and the perceived value of intellectual property.

With the rise of access and trend towards collective intelligence, I definitely see bootleg archives becoming a prominent issue between fans, collectors, academics, copyright holders, and distributors. Currently, we are treading in what is now a minimal space of specialty interest and little monetary profit. But that can clearly change once economic value comes into question of how much can be made in officially releasing or leasing such materials.

Thanks Randy, you bring up some very relevant points.

I am especially taken with your point about the tensions between a gift economy and a market economy. As you say, these bootlegs are generally seen to have very little market value (speciality interest only) and it is worth noting that distributors who attempt to give such rare films commercial releases often struggle to make any money at all. An example would be the Greek company Onar Films, run by Bill Barounis, who have brought out licensed DVDs of niche films such as Süpermen Dönüyor (1979) which had previously only circulated as bootlegs. On the one hand, it was bootlegging which helped generate interest in such films in the first place. Yet, on the other hand, it was the subsequent bootlegging of the licensed DVDs which went on to cause a number of problems for Onar Films and other niche dvd distributors.

As for the reason I didn’t mention anime fansubbers, this is largely due to the relatively low wordcount for FLOW columns. It is definitely an important comparison, though, and I plan to develop this in a future piece of research.

Bonsoir à tous ! J’ai remarqué que votre blog est bien placé sur Google mais des optimisation supplémentaires sont possibles. Possédez-vous des compétences dans ce domaine. Je propose des formations web seo. Pour le cas où, voici mon site