A Parallax Case: Gender Performance in Wings of the Morning

Murray Pomerance / Ryerson University

The male student amuses himself with free flights of thought, and thence come his best inspirations; but woman’s reveries take a very different direction: she will think about her personal appearance, about men, about love; she will give only what is strictly necessary to her studies, her career, when in these domains nothing is so necessary as the superfluous. It is not a matter of mental weakness, of an inability to concentrate, but rather a division between interests difficult to reconcile.

Simone de Beauvoir, The Second Sex, 369

|

|

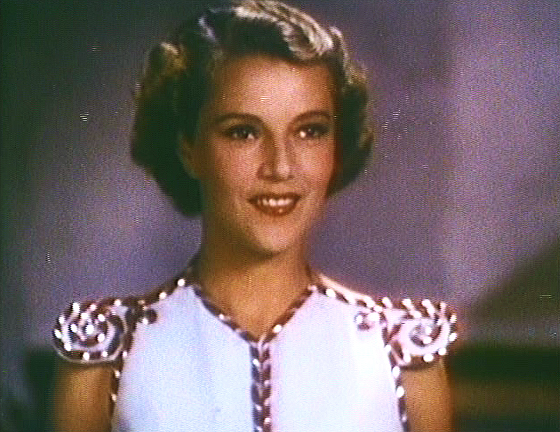

In Wings of the Morning (1937), a young girl, Maria Duchess of Leyva (Annabella), pretends for a sojourn to be a Spanish duke who, mixing with a gypsy colony in Ireland, meets a handsome young Canadian horse trainer, Kerry Gilfallen (Henry Fonda). A number of early scenes engage in a particularly interesting form of gender play, wherein, for example, this “Duke” encounters Kerry in his bath or, later, is forced by circumstances to spend the night in a small barn sleeping with him in the hay. Dressed carefully as a boy, yet at the same time clearly enough for the viewer a girl in disguise, this character puts on a gruff voice and does the best she can with gestures and attitudes befitting a certain bratty masculinity. For his part, Kerry is entirely innocent of the disguise through these scenes, until one particular moment when, having retrieved the Duke’s horse Wings of the Morning and returning with the “boy” and the beast to his camp, he decides they should pause for a pre-breakfast swim in a tranquil lake. The boy runs off “modestly” but Kerry corners him in a huge bush and proceeds (hors scène) to tear off the clothing. As we see shoes and fabric flying out of the leaves we suddenly hear Kerry exclaim, “Oh! I didn’t know!” Not long later, in his estate, the heroine appears in full female regalia at the top of a flight of stairs (regalia decorated with burgundy red, indeed, a color to which the camera was especially sensitive and one which led a viewer to exclaim special delight [see Mayer qtd. in Street 206], inspiring him to gaze in wonder and exclaim, “Holy mackerel! My friend the Duke!” It is at this point, of course, that the two can begin a romance, and this they do, doddling beside a little pool and dipping their feet together, Kerry in a pale yellow turtleneck and Maria in a pale yellow straw hat.1 2 Sharply limning all of these proceedings is the splendid pioneering three-strip Technicolor cinematography by Ray Rennahan and Jack Cardiff: this film was the first shot in Technicolor in England (see Slide 37).3

|

|

The gender game which constitutes the preamble to this love affair is a kind of foreplay, organized according to a central (and, in the cinema of the 1930s and 1940s, frequently reprised) parallax. The young “boy” who is Maria in disguise appears simultaneously one way to Kerry and another way to the audience–who of course view her from a different point, yet she turns her way through the scenes so that the precise angle of sight becomes insignificant.

This receptual parallax is a standard convention in gender disguise plots (such as Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night): the audience must be able to see the disguise as such, just at the same time that a principal character is blinded to it; and in this way the disguise proper, not merely its eventual result, brings viewing pleasure. As in the barn Kerry spoons close to “Mario” in his sleep, we are to imagine him nestling next to a girl he does not yet know he loves while he remains innocent of nestling close to a boy he would (presumably) not wish to nestle close to (an obverse possibility: thinking “Mario” a girl he might love he “transgressively” engages in a homoerotic encounter).

|

|

Kerry’s considerable strengths as a horseman and as a friend to the other adult males in the plot must be openly and seriously compromised by his utter incapacity at discerning “Mario’s” bizarre masculinity. Indeed, while he is distinctly gruff with this “boy” who is afraid of a mouse in the hay, and whose posterior does not seem quite well enough developed for riding the fierce Wings, while he thinks the lad strangely behaved and eccentric, still he gives absolutely no exact indication of finding “Mario” questionable in his masculinity. By the 1950s, the kind of “soft” masculinity purveyed by Maria in her camouflage—a masculinity that is to be read as entirely fabricated, and fabricated, indeed, by someone ill equipped to fabricate—can be read in terms of a discrete gender identity, the effeminate male (or the homosexual): for example, Sal Mineo in Rebel Without a Cause. But here, at least for Kerry, this form of identification is unthinkable, or unthought: the cultural apparatus for subtending the “feminine masculinity,” as it were, has not yet been erected (see as well George Cukor’s Sylvia Scarlett [1935], with Katharine Hepburn’s entirely boyish “Sylvester”).

|

|

“Mario” is taken as fully, completely, independently, and unquestionably male; yet also as badly behaved.

What I wish to point out is not only that, taken seriously, Kerry’s erroneous reading would be insubstantial and inadequate, in itself, for promoting the plot (as it would be: this isn’t a story about a horse trainer meeting a boy); and therefore that it is mandatory we should be given some alternative view, a continuing portrait of “Mario” as a flawed construction being mounted by a (legitimately) conniving young woman; but that the performance must be only a little flawed, or at least, not so flawed as to call into question Kerry’s perception (and thus, his dignity). If we must continually be prodded to see a femininity that he is continually missing, that femininity mustn’t be so categorically obvious that he becomes weak for missing it (note in this light Judith Butler’s consideration of gayness as “necessary drag” in “Imitation” 227ff).4 Nor can the fact that he is missing it be left for attribution to any fault of his own, or to the overriding cinematic convention that binds the elements of this story (and consciousness of which, on our part, would remove us subtly from engagement with the moment). I think it is possible that the maintenance of tension between Maria’s intentions at disguise and Kerry’s (for us, somewhat difficult) naivete is achieved not so much by virtue of what Annabella and Fonda manage to accomplish before the camera (although they are both very precise in directing their gazes, exhibiting poise, and using movement to playfully cajole one another as two young males might) as by virtue of a state of desire that can be taken as applying to the viewer.

Offered two viewing positions at once: that of Kerry, with whom we may identify and whose placement in the scenes we can easily imagine adopting; and our own, outside the film and observing all of this intrigue; we may make a judgment and a choice as to which position offers the deeper, the more exotic, the more tantalizing pleasure. As viewers, we see a woman merely pretending to be a boy who wants to get his horse back, in short, both a performance and its own backstage. This cheapens the masquerade, to the extent that every gesture and nuance is “merely” the result of a conscious strategy. The erotic warmth of human encounter, offered as a possibility in the scenes of these two together, is cooled and distanced as tactic and as achievement. At the same time, the potentially noble Kerry is reduced by every twitch and smirk of Maria’s performance, his keen senses dulled, his desire misled, his masculine sense of self compromised by an apparent inability to detect a beautiful woman in his presence (in spirit, if not in form) and a failure to discern “Mario’s” eccentricities. But if Kerry is an innocent from the viewer’s point of view, he becomes the powerful, pedagogical, playful older male if we see the world as he sees it. Since there will be plenty of time in the story for the encounter in the bush that will reveal Maria for what she is, he may be permitted to enjoy a particular pleasure available to males who encounter younger versions of themselves. He and “Mario” both like horses, they both like to banter, they are both proud. Indeed, the homosocial—and even physical—contact, framed as competition or as friendship, is permissible and exciting, especially with a beautiful stallion protecting the bond.

|

|

Recognizing that Kerry does not see what we see, we have the choice of sincerely holding to our own perspective or thrillingly adopting his, in short, crossing over to the point of view of a young man who cannot discern a young lady when he is confronted by her. And given the pleasures—“transgressive” or not, as the case may be—of affiliating with Kerry’s point of view on “Mario,” the viewer can be relied upon to require only the slightest reminders of Maria’s presence and predicament, none of which actually work to disconnect the viewing intelligence from its bond with the hero. The enticement of the pleasure of watching a male-male bond becomes a fulcrum for the story, since it allows us to value and fix Kerry as our center of emotional connection. Also, and more importantly, this possibility of pleasure energizes a central narrative mechanism by which the viewer comes into engagement with purely fictive points of view. When Maria is revealed and Kerry falls in love with her, we may share that love. Bonded through perspective with him, we are readied to share his excitement at the moment of discovering with surprise what in another life we already knew.

With thanks to Wheeler Winston Dixon and Graeme Metcalf

Image Credits:

Stills Captured by Author

Please feel free to comment.

- Mayer, J. P. British Cinemas and their Audiences. London: Dennis Dobson, 1948. [↩]

- Street, Sarah. “‘Colour consciousness’: Natalie Kalmus and Technicolor in Britain,” Screen 50: 2 (Summer 2009), 191-215. [↩]

- Slide, Anthony.”Wings of the Morning: an Important Film,” American Cinematographer 67: 2 (February 1986), 36-40. [↩]

- Butler, Judith. “Imitation and Gender Insubordination,” in John Storey, ed., Cultural Theory and Popular Culture: A Reader, 4th edn., Harlow: Pearson Education, 2009, 224-38. [↩]